Kent Island Design Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Initial Study/Environmental Assessment: Kent Island Restoration at Bolinas Lagoon

DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT: KENT ISLAND RESTORATION AT BOLINAS LAGOON Marin County Open Space District and US Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District August 2012 DRAFT INITIAL STUDY/ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT: KENT ISLAND RESTORATION AT BOLINAS LAGOON PREPARED FOR Marin County Open Space District Marin County Civic Center 3501 Civic Center Drive, Room 260 San Rafael, CA 94903 (415) 499-6387 and US Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District 1455 Market St San Francisco, CA 94103 (415) 503-6703 PREPARED BY Carmen Ecological Consulting Grassetti Environmental Consulting Peter R. Baye, Coastal Ecologist, Botanist August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................1 1.1 Purpose of this Document ............................................................................................................1 1.2 Document Structure ..............................................................................................................1 2.0 PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES .......................................................................3 2.1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................3 2.2 Environmental Setting ..............................................................................................................3 2.3 Purpose and Need ..............................................................................................................6 -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Revised July 11, 2000

Revised January 29, 2013 U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan Upper Mississippi Valley/ Great Lakes Regional Shorebird Conservation Plan Version 1.0 Prepared by1: Ferenc de Szalay, Department of Biological Sciences, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio Doug Helmers, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Columbia, Missouri Dale Humburg, Missouri Department of Conservation, Columbia, Missouri Stephen J. Lewis, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota Barbara Pardo, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Fort Snelling, Minnesota Mark Shieldcastle, Ohio Division of Wildlife, Oak Harbor, Ohio May, 2000 1 Authors are listed alphabetically. Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE UMVGL REGION ................................................................................ 2 Physical Description ............................................................................................................... 2 Bird Conservation Regions ..................................................................................................... 2 Shorebird Habitats in the UMVGL ......................................................................................... 3 Human Impacts on Shorebird habitat in the UMVGL Region ............................................... 4 SHOREBIRD SPECIES -

List of Species Likely to Benefit from Marine Protected Areas in The

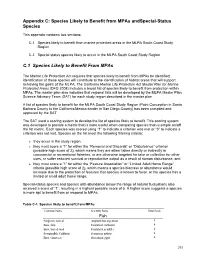

Appendix C: Species Likely to Benefit from MPAs andSpecial-Status Species This appendix contains two sections: C.1 Species likely to benefit from marine protected areas in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.2 Special status species likely to occur in the MLPA South Coast Study Region C.1 Species Likely to Benefit From MPAs The Marine Life Protection Act requires that species likely to benefit from MPAs be identified; identification of these species will contribute to the identification of habitat areas that will support achieving the goals of the MLPA. The California Marine Life Protection Act Master Plan for Marine Protected Areas (DFG 2008) includes a broad list of species likely to benefit from protection within MPAs. The master plan also indicates that regional lists will be developed by the MLPA Master Plan Science Advisory Team (SAT) for each study region described in the master plan. A list of species likely to benefit for the MLPA South Coast Study Region (Point Conception in Santa Barbara County to the California/Mexico border in San Diego County) has been compiled and approved by the SAT. The SAT used a scoring system to develop the list of species likely to benefit. This scoring system was developed to provide a metric that is more useful when comparing species than a simple on/off the list metric. Each species was scored using “1” to indicate a criterion was met or “0” to indicate a criterion was not met. Species on the list meet the following filtering criteria: they occur in the study region, they must score a “1” for either -

Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy

TOLL FACILITIES IN THE UNITED STATES Bridges - Roads - Tunnels - Ferries August 2009 Publication No: FHWA-PL-09-00021 Internet: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/tollpage.htm Toll Roads in the United States: History and Current Policy History The early settlers who came to America found a land of dense wilderness, interlaced with creeks, rivers, and streams. Within this wilderness was an extensive network of trails, many of which were created by the migration of the buffalo and used by the Native American Indians as hunting and trading routes. These primitive trails were at first crooked and narrow. Over time, the trails were widened, straightened and improved by settlers for use by horse and wagons. These became some of the first roads in the new land. After the American Revolution, the National Government began to realize the importance of westward expansion and trade in the development of the new Nation. As a result, an era of road building began. This period was marked by the development of turnpike companies, our earliest toll roads in the United States. In 1792, the first turnpike was chartered and became known as the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike in Pennsylvania. It was the first road in America covered with a layer of crushed stone. The boom in turnpike construction began, resulting in the incorporation of more than 50 turnpike companies in Connecticut, 67 in New York, and others in Massachusetts and around the country. A notable turnpike, the Boston-Newburyport Turnpike, was 32 miles long and cost approximately $12,500 per mile to construct. As the Nation grew, so did the need for improved roads. -

Pacific Ocean

124° 123° 122° 121° 42° 42° 39 38 37 36 35 34 33 ° 32 41° 41 31 29 30 27 28 26 25 24 23 22 21 ° ° 40 20 40 19 18 17 16 15 PACIFIC OCEAN 14 13 ° ° 39 12 39 11 10 9 8 6 7 4 5 20 0 20 3 MILES 1 2 38° 38° 124° 123° 122° 121° Prepared for: Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department Of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sacramento, California Seattle, Washington Prepared by: RESEARCH PLANNING, INC. Columbia, SC 29202 ENVIRONMENTAL SENSITIVITY INDEX MAP 123°00’00" 122°52’30" 38°07’30" 38°07’30" TOMALES BAY STATE PARK P O I N T R E Y E S N A T I O N A L S E A S H O R E ESTERO DE LIMANTOUR RESERVE POINT REYES NATIONAL SEASHORE 38°00’00" 38°00’00" POINT REYES HEADLAND RESERVE GULF OF THE FARALLONES NATIONAL MARINE SANCTUARY 123°00’00" 122°52’30" ATMOSPH ND ER A IC IC A N D A M E I Prepared for C N O I S L T R A A N T O I I O T N A N U . E S. RC DE E PA MM RTMENT OF CO Office of HAZARDOUS MATERIALS RESPONSE OIL SPILL PREVENTION and RESPONSE and ASSESSMENT DIVISION California Department of Fish and Game National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 1.50 1KILOMETER 1.50 1MILE PUBLISHED: SEPTEMBER 1994 DRAKES BAY, CALIF. -

2008 ANNUAL REPORT the Mission of the Marin Conservation League Is to Preserve, Protect and Enhance the Natural Assets of Marin County

Protecting Marin Since 1934 2008 ANNUAL REPORT The mission of the Marin Conservation League is to preserve, protect and enhance the natural assets of Marin County. MARIN CONSERVATION LEAGUE Dear Friends: BOARD OF DIRECTORS Offi cers Nona Dennis, Mill Valley, President It is my pleasure, on behalf of the Marin Conservation League Board of Daniel Sonnet, San Rafael, Directors, to report the League’s activities in 2008. You – the members First Vice President and supporters of MCL – are the foundation of this organization, and Roger Roberts, San Rafael we honor and thank you! Without your support, our accomplishments Second Vice President would not be possible. Larry Smith, Nicasio, Secretary Kenneth Drexler, Fairfax, Treasurer Directors This year was the League’s 74th year – an opportunity to review MCL’s Peter Asmus, Stinson Beach legacy and begin planning for our 75th anniversary. The most powerful lesson to emerge Betsy Bikle, Mill Valley from this legacy is that although decades have passed since MCL’s founding, the land Priscilla Bull, Kentfi eld protection tools, tactics, and strategies that were championed by the League’s founders are Joe Bunker, San Anselmo timeless – as relevant in 2008 as they were in 1934! The Action Calendar on pages 6 and 7 Carson Cox, Mill Valley provides abundant evidence of this truism. Bruce Fullerton, Mill Valley Jana Haehl, Corte Madera 2008 began with little warning of the economic diffi culties it would present. Now as Brannon Ketcham, Fairfax 2008 has turned into 2009, it is clear that economic downturn is having an impact on Marge Macris, Mill Valley environmental projects around the State. -

First Record of Long-Billed Curlew Numenius Americanus in Peru and Other Observations of Nearctic Waders at the Virilla Estuary Nathan R

Cotinga 26 First record of Long-billed Curlew Numenius americanus in Peru and other observations of Nearctic waders at the Virilla estuary Nathan R. Senner Received 6 February 2006; final revision accepted 21 March 2006 Cotinga 26(2006): 39–42 Hay poca información sobre las rutas de migración y el uso de los sitios de la costa peruana por chorlos nearcticos. En el fin de agosto 2004 yo reconocí el estuario de Virilla en el dpto. Piura en el noroeste de Peru para identificar los sitios de descanso para los Limosa haemastica en su ruta de migración al sur y aprender más sobre la migración de chorlos nearcticos en Peru. En Virilla yo observí más de 2.000 individuales de 23 especios de chorlos nearcticos y el primer registro de Numenius americanus de Peru, la concentración más grande de Limosa fedoa en Peru, y una concentración excepcional de Limosa haemastica. La combinación de esas observaciones y los resultados de un estudio anterior en el invierno boreal sugiere la posibilidad que Virilla sea muy importante para chorlos nearcticos en Peru. Las observaciones, también, demuestren la necesidad hacer más estudios en la costa peruana durante el año entero, no solemente durante el punto máximo de la migración de chorlos entre septiembre y noviembre. Shorebirds are poorly known in Peru away from bordered for a few hundred metres by sand and established study sites such as Paracas reserve, gravel before low bluffs rise c.30 m. Very little dpto. Ica, and those close to metropolitan areas vegetation grows here, although cows, goats and frequented by visiting birdwatchers and tour pigs owned by Parachique residents graze the area. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Although much of the San Francisco Bay Region is densely populated and industrialized, many thousands of acres within its confines have been set aside as parks and preserves. Most of these tracts were not rescued until after they had been altered. The construction of roads, the modification of drainage patterns, grazing by livestock, and the introduction of aggressive species are just a few of the factors that have initiated irreversible changes in the region’s plant and animal life. Yet on the slopes of Mount Diablo and Mount Tamal- pais, in the redwood groves at Muir Woods, and in some of the regional parks one can find habitats that probably resemble those that were present two hundred years ago. Even tracts that are far from pristine have much that will bring pleasure to those who enjoy the study of nature. Visitors to our region soon discover that the area is diverse in topography, geology, cli- mate, and vegetation. Hills, valleys, wetlands, and the seacoast are just some of the situa- tions that will have one or more well-defined assemblages of plants. In this manual, the San Francisco Bay Region is defined as those counties that touch San Francisco Bay. Reading a map clockwise from Marin County, they are Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco. This book will also be useful in bordering counties, such as Mendocino, Lake, Santa Cruz, Monterey, and San Benito, because many of the plants dealt with occur farther north, east, and south. For example, this book includes about three-quarters of the plants found in Monterey County and about half of the Mendocino flora. -

MARTIN GRIFFIN an Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2015

Mill Valley Oral History Program A collaboration between the Mill Valley Historical Society and the Mill Valley Public Library MARTIN GRIFFIN An Oral History Interview Conducted by Debra Schwartz in 2015 © 2015 by the Mill Valley Public Library TITLE: Oral History of Martin Griffin INTERVIEWER: Debra Schwartz DESCRIPTION: Transcript, 37 pages INTERVIEW DATE: October 20th, 2015 In this oral history, physician, naturalist, champion of open spaces and bane of developers Martin Griffin recounts with warmth and humor his long and extraordinarily active life. Born in Ogden, Utah, in 1920 to nature-loving parents, Martin moved with his family to Portland, Oregon, when the Great Depression hit, and then down to Los Angeles and finally up to Oakland, where he attended elementary school through high school. Martin recalls some early experiences that shaped his love for the environment, including his involvement with the Boy Scouts, where he met the graduate student entomologist Brighton C. “Bugs” Cain, who profoundly inspired him. It was also as a boy that Martin came over to Mill Valley for the first time, making his way by ferry and train, to go hiking on Mt. Tamalpais. He conjures the beautiful vision he had from the ridge that day of white birds down on Bolinas Lagoon, a vision which made such a powerful impression on him and would, years later, feed the flames of his conservationist passion. Martin recounts being involved in ROTC while an undergraduate at U.C. Berkeley, later attending medical school at Stanford, where he got married, and moving over to Marin to begin his medical practice. -

Smscindexpp266-273.Pdf

INDEX References to illustrations are printed in italics. Ablin, Debbie, 42,92, 258 Azevedo, Margaret, 129 Bolinas-Stinson Beach Master Plan, Adelman, Brenda, 220, 222, 251, 260 34 Aggregate, 243-245, 257 Bagley, Bill, 120 Bolling, David, 224,260 Aggregate Resources Management Bahia Baulinas, 61 Bostick, Benton, 20, 22 (ARM) Plan, 205-206, 256, 257 Ballard, Allan, 87 Bostick, Dr. Warren, 20, 22 Agricultural and Aquifer Baptiste, Arnold, 107 Bouverie Audubon Preserve, xix, Preservation Zone, 205 Barbour, Nancy, 42, 92, 258 152, 153,155-159,258-259 Ah Pah Dam, 163 Barfield, Tom, 63 Bouverie, David, xix, 157, 159,254 Alexander Valley Reach, 236 Bay Conservation and Development Boxer, Senator Barbara, 93, 127,139 Alexander, Meg, 225,260 Commission, 18 Boyd, Rhoda, 67 Allen, Howard B„ 76,93,115,258-259 Beeby, David, 244 Brandt-Hawley, Susan, 208-209, 260 American River, 6 Behr, Peter, 66, 71, 89,97, 107, 128- Bransom-Cooke, Admiral, 65, 67 Anderson, Bruce, 200 129, 132,142,162,171, 191, Brower, David, 113 Angel Island, 12, 27 239,251 Brown, Governor Jerry, 168 Anton, John, 140 biography, 129,169 Brown, Governor Pat, xii, 33 Aquifers, importance of, 162-163 “Belling the cat”, 113,114, 205,207, Brown, Wishard, 148 See also Middle Reach; Sonoma- 209 Burge, Bob, 86 Marin Aquifer Benoist, Jay, 217 Army Corps of Engineers, 143,170, Benthos, 99 Cain, Brighton “Bugs,” 6 , 32,42 218 Bianchi, Al, 120 Cale, Mike, 192 and Bolinas Lagoon, 59, 81 Big Sulfur Creek, 152, 153 California Coastal Act of 1976, xiii, and Coyote Dam, 18, 33, 187 Bird research, 74-75 255 and Warm Springs Dam, 140, 188 Birds.