Alternative Infrastructures of Care for the Underclass in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Journal L 60 of the European Union

Official Journal L 60 of the European Union ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Volume 59 English edition Legislation 5 March 2016 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/311 of 4 March 2016 implementing Regulation (EU) No 208/2014 concerning restrictive measures directed against certain persons, entities and bodies in view of the situation in Ukraine .................................................................... 1 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/312 of 4 March 2016 correcting Regulation (EU) No 37/2010 as regards the substance ‘tylvalosin’ (1) ....................................................... 3 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/313 of 1 March 2016 amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 680/2014 with regard to additional monitoring metrics for liquidity reporting (1) ....................................................................................................... 5 ★ Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/314 of 4 March 2016 amending Annex III to Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council on cosmetic products (1) 59 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/315 of 4 March 2016 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 329/2007 concerning restrictive measures against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea ........................................................................................................... 62 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2016/316 of 4 March 2016 establishing the standard import values for determining -

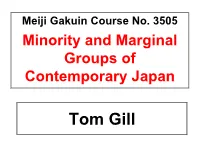

Tom Gill Lecture No

Meiji Gakuin Course No. 3505 Minority and Marginal Groups of Contemporary Japan Tom Gill Lecture No. 4 Koreans 在日コリアン HISTORY 1. Ancient History • Korean kings thought to be buried at Nara; many archaeological finds show Korean influence on Japan. • Also Chinese influence via Korea – Confucianism, kanji etc. • Koreans in Japan today like to point out Japan’s cultural debt to Korea. Ancient Japanese burial mounds … 塚・古墳 … may conceal remains of Korean kings? … the Japanese government doesn’t want to know. Radical emperor? During a news conference to mark his 68th birthday, Emperor Akihito mentioned a historical document showing that one of his eighth- century ancestors was a descendant of immigrants from the Korean Peninsula. He said he felt a close "kinship" with Korea. 『続日本記』によると The Emperor, quoting from the "Shoku Nihongi" ("Chronicles of Japan"), compiled in 797, said the mother of Emperor Kanmu (737- 806) had come from the royal family of Paekche, an ancient kingdom of Korea. 桓武天皇の母親はコリアの皇室出身者 It was the first time a member of the Imperial family had ever publicly noted the family's blood ties with 23 Korea. December 2002 韓国で大歓迎 His remark received a warm welcome in Seoul. South Korean President Kim Dae Jung praised the Emperor for his "correct understanding of history." 手を上げてください I wonder how many of the Meigaku students here today know that Emperor Akihito himself has stated that he is of Korean descent? 明学の学生たち、明仁天皇自身が朝鮮の ルーツを認めているて、知っています か? 朝日だけ報道した Of the five national papers, the Mainichi, the Yomiuri, the Sankei and the Nihon Keizai Shinbun ignored the Emperor's Korea reference. -

North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea)

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Page 1 of 21 CONSOLIDATED LIST OF FINANCIAL SANCTIONS TARGETS IN THE UK Last Updated:08/11/2018 Status: Asset Freeze Targets REGIME: North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) INDIVIDUALS 1. Name 6: IL 1: KIM KYONG 2: n/a 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 01/08/1979. a.k.a: KYO'NG-IL, Kim Passport Details: Passport No. 836210029 Address: Libya. Position: Foreign Trade Bank deputy chief representative in Libya Other Information: Annex XIII. UN Listing. UN Ref.KPI.067. Listed on: 22/12/2017 Last Updated: 09/01/2018 Group ID: 13562. 2. Name 6: AN 1: JONG 2: HYUK 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 14/03/1970. a.k.a: AN , Jong , Hyok Passport Details: Passport Number. 563410155 Position: Diplomat DPRK Embassy Egypt Other Information: Annex XVI EU Listing not UN. Representative of Saeng Pil Trading Corporation, an alias of Green Pine Associated Corporation, and DPRK diplomat in Egypt. Listed on: 22/01/2018 Last Updated: 22/01/2018 Group ID: 13590. 3. Name 6: BONG 1: PAEK 2: SE 3: n/a 4: n/a 5: n/a. DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Other Information: Annex XIII [UN Listing (formerly temporary listing, in accordance with Policing and Crime Act 2017]. UN Reference KPi.048. Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID). -

Andrei Lankov FORGOTTEN PEOPLE: the KOREANS of THE

Andrei Lankov FORGOTTEN PEOPLE: THE KOREANS OF THE SAKHALIN ISLAND IN 1945-1991 In early spring 1946, hundreds of Korean miners and fishers came to a small port city of Korsakov, located in the sounthernmost part of the Sakhalin island. Southern Sakhalin just changed ownership: after 40 years of the Japanese rule, its territory was retaken by the Russians, so local Japanese were moving back to their native islands. Koreans came to Korsakov because rumors which insisted: ships would soon arrive to take all Koreans from Sakhalin back home, to southern provinces of newly independent Korea. Those who came to Korsakov wanted to be first to board these ships. However, ships never came. This was, in a sense, a sign of things to come. The Sakhalin Koreans found themselves locked at the island in 1945 (much against their will) and for long time they hoped for some miracle which will let them return to their homes. This miracle did happen eventually, but only when it was too late for most of them, and when their children and grandchildren had completely different ideas about how life should be lived. The present article is largely based on the material which were collected during the author’s trip to Sakhalin in 2009. In recent years the local historians have produced a number of high- quality studies of the Sakhalin Koran community and its history. Unfortunately, these through and interesting studies are not well-known even in Russia outside the island, let alone overseas. The present article is based on the notes and materials provided by the Sakhalin historians and activists, as well as on some publications. -

Case 1:20-Cr-00032-RC Document 1 Filed 02/05/20 Page 1 of 50

Case 1:20-cr-00032-RC Document 1 Filed 02/05/20 Page 1 of 50 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Holding a Criminal Term Grand Jury Sworn in on May 3, 2018 ) CRIMINAL NO. ______________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) VIOLATIONS: Plaintiff, ) ) 18 U.S.C. § 371 v. ) (Conspiracy) ) KO CHOL MAN, ) 50 U.S.C. § 1705 ) (International Emergency Economic KIM SONG UI, ) Powers Act Violation) ) HAN UNG, ) 31 C.F.R. 544.201 and 544.205 ) (Weapons of Mass Destruction RI JONG NAM, ) Proliferators Sanctions Regulations) JO UN HUI, ) ) 31 C.F.R. 510.201 and 510.206 (North Korea Sanctions Regulations) O SONG HUI, ) ) RI MYONG JIN, ) 18 U.S.C. § 1344 ) (Bank Fraud) RI JONG WON, ) 18 U.S.C. § 1956(h) ) (Conspiracy to Launder Monetary JONG SUK HUI, ) Instruments) ) KIM TONG CHOL, ) 18 U.S.C. § 1956(a)(2)(A) ) KIM CHIN a/k/a KIM JIN, (International Money Laundering) ) ) HUANG HAILIN, 18 U.S.C. § 1956(h) ) (Continuing Financial Crimes Enterprise) HUANG YUEQING, ) ) JIN YONGHE, ) FORFEITURE: ) SUN WEI, ) 18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(1) RI CHUN HWAN, ) 18 U.S.C. § 982(a)(2)(A) ) 18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(A) KIM HUI SUK, ) 18 U.S.C. § 981(a)(1)(C) ) 21 U.S.C. § 853(p) HAN YONG CHOL, ) 28 U.S.C. § 2461(c) 1 Case 1:20-cr-00032-RC Document 1 Filed 02/05/20 Page 2 of 50 ) RI CHUN SONG, ) ) RI JONG CHOL, ) ) KIM KWANG CHOL, ) RI YONG SU, ) ) KU JA HYONG, ) ) JIN YONGHUAN, ) ) KWON SONG IL, ) ) RYU MYONG IL, ) ) HYON YONG IL, ) HWANG WON JUN, ) ) HAN KI SONG, ) ) HAN JANG SU, ) ) RI MYONG HUN, ) ) KIM KYONG NAM, ) ) and KIM HYOK JU, ) ) Defendants. -

Commission Implementing Regulation (Eu

9.6.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 146/129 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2017/970 of 8 June 2017 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 329/2007 concerning restrictive measures against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 329/2007 of 27 March 2007 concerning restrictive measures against the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (1), and in particular Article 13(1)(d) thereof, Whereas: (1) Annex IV to Regulation (EC) No 329/2007 lists persons, entities and bodies who, having been designated by the Sanctions Committee or the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), are covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. (2) On 2 June 2017, the UNSC adopted Resolution 2356 (2017) adding 14 natural persons and four entities to the list of persons and entities subject to restrictive measures. On 1 June 2017, the Sanctions Committee also amended the listing of four existing entries. (3) Annex IV should therefore be amended accordingly. (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into force immediately, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Article 1 Annex IV to Regulation (EC) No 329/2007 is amended in accordance with the Annex to this Regulation. Article 2 This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. -

Official Journal L146

Official Journal L 146 of the European Union ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Volume 60 English edition Legislation 9 June 2017 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Council Regulation (EU) 2017/964 of 8 June 2017 amending Regulation (EU) No 267/2012 concerning restrictive measures against Iran ....................................................................... 1 ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/965 of 8 June 2017 implementing Article 2(3) of Regulation (EC) No 2580/2001 on specific restrictive measures directed against certain persons and entities with a view to combating terrorism and amending Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/150 ................................................................................................ 6 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/966 of 1 June 2017 approving non-minor amendments to the specification for a name entered in the register of protected designations of origin and protected geographical indications (Connemara Hill Lamb/Uain Sléibhe Chonamara (PGI)) ............................................................................................................ 8 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/967 of 8 June 2017 granting Cape Verde a temporary derogation from the rules on preferential origin laid down in Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/2446, in respect of prepared or preserved fillets of tuna ....................... 10 ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/968 of 8 June 2017 granting Cape Verde a temporary derogation from the rules on preferential -

Annex to This News Release

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF KOREA COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 2016/315 AMENDING ANNEXs IV and V TO COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 329/2007 ADDITIONS Individuals 1. CHOE, Chun-Sik DOB: 12/10/1954. a.k.a: (1) CHOE, Chun Sik (2) CH'OE, Ch'un Sik Nationality: North Korean Other Information: Annex IV. UN listing. Chun-sik was the director of the Second Academy of Natural Sciences (SANS) and was the head of the DPRK's long-range missile program. Listed on: 05/03/2016 Last Updated: 05/03/2016 Group ID: 13324. 2. CHOE, Song Il Nationality: North Korean Passport Details: Passport No: (a) 472320665 (Date of Expiration: 26.9.2017), (b) 563120356. Position: Tanchon Commercial Bank Representative in Vietnam Other Information: Annex IV. UN listing. Listed on: 05/03/2016 Last Updated: 05/03/2016 Group ID: 13325. 3. HYON, Kwang Il DOB: 27/05/1961. a.k.a: HYON, Gwang Il Nationality: North Korean Position: Department Director for Scientific Development at the National Aerospace Development Administration Other Information: Annex IV. UN listing. Listed on: 05/03/2016 Last Updated: 05/03/2016 Group ID: 13326. 4. JANG, Bom Su DOB: 15/04/1957. Nationality: North Korean Position: Tanchon Commercial Bank Representative in Syria Other Information: Annex IV. UN listing. Listed on: 05/03/2016 Last Updated: 05/03/2016 Group ID: 13327. 5. JANG, Yong Son DOB: 20/02/1957. Nationality: North Korean Position: Korea Mining Development Trading Corporation (KOMID) Representative in Iran Other Information: Annex IV. UN listing. Listed on: 05/03/2016 Last Updated: 05/03/2016 Group ID: 13328. -

Annex to Notice

ANNEX TO NOTICE FINANCIAL SANCTIONS: NORTH KOREA (DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA) COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) No 2017/1509 AMENDMENTS Deleted information appears in strikethrough. Additional information appears in italics and is underlined. Individuals 1. BONG Paek Se DOB: 21/03/1938. Nationality: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Other Information: Annex XIII [UN Listing (formerly temporary listing, in accordance with Policing and Crime Act 2017]. UN and EU listing. UN Reference KPi.048. Former Chairman of the Second Economic Committee, a former member of the National Defense Commission, and a former Vice Director of Munitions Industry Department (MID). Listed on: 05/06/2017 Last Updated: 12/06/2017 15/09/2017 Group ID: 13478. 2. CHANG Chang Ha DOB: 10/01/1964. a.k.a: JANG, CHANG, HA Nationality: DPRK Position: President of the Second Academy of Natural Sciences (SANS) Other Information: Annex XIII UN Listing. UN Reference KPi.037 Date of UN designation 30.11.2016 Listed on: 09/12/2016 Last Updated: 09/12/2016 15/09/2017 Group ID: 13422. 3. CHANG Myong-Chin DOB: (1) --/--/1966. (2) --/--/1965. (3) 19/02/1968. a.k.a: JANG, Myong-Jin Position: General Manager of the Sohae Satellite Launching Station. Head of launch center. Other Information: Annex IV. XIII UN Listing UN Reference KPi.007. Head of launch center at which the 13 April and 12 December 2012 launches took place. Gender: male. Listed on: 19/02/2013 Last Updated: 17/10/2014 15/09/2017 Group ID: 12844. 4. CHI Bu Chon a.k.a: CHON, Chi-bu Position: Member of the General Bureau of Atomic Energy. -

Do You Know? All EU Passports Are in Burgundy Color. Croatia Is the Only

BLOG Tweets by @passportmuseum World Passport Museum @passportmuseum Do you know? All EU passports are in Burgundy color. Croatia is the only passport that has odd looking blue color amongst EU passport, since the country refused to adopt common passport adopt common passport standards since EU accession.#passportcover Apr 11, 2020 World Passport Museum @passportmuseum Worst Pandemics 1. Black Plague death - 200M deaths (1347-1351) 2. Small Pox - 56M (1520) 3. Spanish Flu - 50M (1919) 4. Justinian Plague - 30-50M (541 AD)visualcapitalist.com/histo ry-of-pan… Visualizing the History of Pandemics The history of pandemics, from the Antonine Plague to the ongoing COVID-19 event, ranked by their impact on human vlifiseu. alcapitalist.com Mar 20, 2020 World Passport Museum @passportmuseum Photo identification first appeared in 1876. It was not become widely used until the early 20th century to strengthen the security of passports and ID docs Australia and Great Britain introduced requirement for a photographic passport in 1915 after Lody spy scandal 1853 photo Mar 9, 2020 World Passport Museum @passportmuseum The Earliest identity document inscribed into law was introduced by King Henry V of England with the Safe Conducts Act 1414 It was not for the next 500 years until World War I, most people did not have or need for an identity document. Mar 9, 2020 World Passport Museum @passportmuseum USCIS History 1891 - US Gov created Office of Immigration under Treasury 1895 - Upgraded to Bureau of Immigration 1906 - Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization 1933 - Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) 2003 - INS dismantled becoming USCIS, ICE and CBP under DHS Feb 29, 2020 World Passport Museum @passportmuseum Royal Messengers carried sensitive royal messages sensitive royal messages since the 15th century. -

Chongryon's Enduring Legacy: Uncertain Future of Resident North

Chongryon’s Enduring Legacy: Uncertain Future of Resident North Koreans in Japan by Kylie Sertic B.A. in Japanese Language and Culture, May 2013, University of Puget Sound A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Elliott School of International Affairs of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts January 31, 2017 Thesis directed by Daqing Yang Associate Professor of History and International Affairs Abstract of Thesis Chongryon’s Enduring Legacy: Uncertain Future of Resident North Koreans in Japan “This Master’s thesis seeks to understand the future of the organization of Chongryon, the North Korean homeland oriented organization in Japan, and their influence in the Zainichi community of Japan. Chongryon dominated as the main civil society group of the Korean community in Japan during the mid-twentieth century. However, in the twenty-first century their membership is declining and they have faced many conflicts with the law in Japan, leading to speculation that the group might cease to exist in the future. Through an examination of Chongryon’s own website as a primary source to assess the group’s public image and stated core values, as well as a thorough examination of the history of the organization through various challenges in the mid to late twentieth century, this paper argues that the staying power of Chongryon will outlast the current issues, even if it has reduced influence in the Korean community. The group has endured despite crackdowns on their illegal activities -

Discourses of a Zainichi Korean Athlete in South Korea: Possibilities and Limits for De-Colonial and De-Cold War Imagination”

Program in Transnational Korean Studies Presents: “Discourses of a Zainichi Korean Athlete in South Korea: Possibilities and Limits for de-colonial and de-Cold War Imagination” Dr. Younghan Cho Associate Professor, Korean Studies Hankuk University of Foreign Studies, Seoul, Korea This study examines how the re-configuration of zainichi Korean subjectivities reveals both the continuity and rupture of colonial and Cold War systems in the 21st century South Korea. For this purpose, it examines South Korean discourses on Jong Tae-se, a zainichi Korean soccer player born in Nagoya, Japan as a third-generation Japanese-resident Korean. Jong has Date become a national star in Japan, North Korea and South Korea, and also Thursday, February attracted global media attention by playing in the 2010 World Cup as a member 4, 2016 of the North Korean national team. Afterwards, Jong has played for several professional clubs in Japan and Germany, and is currently a member of the Time Suwon Samsung Bluewings in South Korea. As a global sport star, he seems to 4:00-6:00pm exemplify a new generation of a zainichi Korean, who is celebrated for culturally diversified and flexible identities. As a migrating sport athlete, furthermore, he Location often exemplifies flexible citizenship, one who neither belongs to any nation, Humanities & Social nor is limited by fixed or essentialist notions of nationality. While he holds South Sciences Korean citizenship (through his father), he decided to play for North Korea, Room 4025 which issued him a travel passport. Put simply, Jong is a South Korean citizen, a North Korean passport holder, and a Japanese permanent resident.