The Role of Locus of Control in Nyaope Addiction: a Mixed Method Study in Gauteng

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 01:39:54PM Via Free Access S

SHERI HAMILTON 17. PEDAGOGY OF STRUGGLE #OutsourcingMustFall INTRODUCTION In October 2015, 10000 university students gathered at the Union Buildings in Pretoria, South Africa’s administrative capital, to demand the scrapping of proposed fee increases and the insourcing of workers. #FeesMustFall (FMF), the banner adopted, unified protests initially directed against apartheid-like practices such as language policies and colonial symbols at historically white universities. At its height, FMF demonstrated the potential to unite the decade-long, often militant but uncoordinated student protests against academic and financial exclusions mainly at historically black universities. It was the FMF’s economic demands – no fee increases – that enabled it to grow into a national movement that forced the government to concede. This demand united the majority of students – the poorest, the ‘missing middle’1 – and attracted the sympathies of wealthier students. FMF not only temporarily halted fee increases, but secured in-principle agreements to scrap the outsourcing of workers at some historically white universities – a practice that was embedded in the restructuring of higher education rooted in the neoliberal economic policy, Growth Employment and Redistribution, adopted in 1996 by the African National Congress (ANC)-led government. As fresh protests broke out a year later following the announcement of fee increases that will be capped at eight per cent for the 2017 academic year, the threat to student unity is posed by differentially applied increases. Students are demanding free education while government has exempted poor students who are recipients of its loan scheme, excluding the ‘missing middle’ for whose funding government is appealing to the private sector. -

The Power of Heritage to the People

How history Make the ARTS your BUSINESS becomes heritage Milestones in the national heritage programme The power of heritage to the people New poetry by Keorapetse Kgositsile, Interview with Sonwabile Mancotywa Barbara Schreiner and Frank Meintjies The Work of Art in a Changing Light: focus on Pitika Ntuli Exclusive book excerpt from Robert Sobukwe, in a class of his own ARTivist Magazine by Thami ka Plaatjie Issue 1 Vol. 1 2013 ISSN 2307-6577 01 heritage edition 9 772307 657003 Vusithemba Ndima He lectured at UNISA and joined DACST in 1997. He soon rose to Chief Director of Heritage. He was appointed DDG of Heritage and Archives in 2013 at DAC (Department of editorial Arts and Culture). Adv. Sonwabile Mancotywa He studied Law at the University of Transkei elcome to the Artivist. An artivist according to and was a student activist, became the Wikipedia is a portmanteau word combining youngest MEC in Arts and Culture. He was “art” and “activist”. appointed the first CEO of the National W Heritage Council. In It’s Bigger Than Hip Hop by M.K. Asante. Jr Asante writes that the artivist “merges commitment to freedom and Thami Ka Plaatjie justice with the pen, the lens, the brush, the voice, the body He is a political activist and leader, an and the imagination. The artivist knows that to make an academic, a historian and a writer. He is a observation is to have an obligation.” former history lecturer and registrar at Vista University. He was deputy chairperson of the SABC Board. He heads the Pan African In the South African context this also means that we cannot Foundation. -

President Zuma Launches Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University

President Zuma launches Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Siyabonga Nxumalo President Jacob Zuma and the Minister of Higher Education and Training, Dr Blade Nzimande officially launched the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University in Garankuwa, Pretoria on the 14th of April 2015. Sefako Makgato Health Sciences University opened its doors in January 2015 after a de‐merger from the University of Limpopo. The new university will go beyond training medical doctors. It will also produce other health professionals such as dentists, nurses, physiotherapists, medical technologists, radiographers and many more. Currently the university has enrolled 5034 students and the number of students enrolling is expected to increase to 7000 by 2019 and 10 000 by 2024. President Zuma said that South Africa is faced with an extensive shortage and an inadequate distribution of health professionals. “The country has an undersupply of new and appropriately trained health science graduates. The establishment of Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University therefore provides an excellent opportunity for the development and training of a new generation of health professionals who will make a positive impact on the lives and livelihoods of the many South Africans still marginalised by poverty and lack of access to health services” said Zuma. Historic moment: President of the Republic, His Excellency Jacob Zuma and the Minister of Higher Education and Training, Dr Blade Nzimande unveil the statue of the late former President of the ANC Mr Sefako Mapogo Makgatho at the launch of the Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University in Garankuwa, Pretoria on the 14th of June 2015. The university is the first stand‐alone health sciences university in the country. -

Size: 4 MB 14Th Nov 2019 2ND NPA DISCUSSION DOCUMENT A4

Consolidating the ground towards socialist power! Table of content ORGANISATIONAL CHARACTER ............................................................................ 2 AND RE-DESIGN .................................................................................................... 2 LAND AND AGRARIAN REFORM .......................................................................... 33 ON GENDER STRUGGLES.................................................................................... 53 MEDIA, COMMUNICATIONS AND THE BATTLE OF IDEAS .................................... 67 HEALTH ............................................................................................................. 103 SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT ..................................................................................... 118 EDUCATION ..................................................................................................... 127 PAN AFRICANISM AND PROGRESSIVE INTERNATIONALISM ............................... 151 THE ECONOMY ................................................................................................ 168 STATE CAPACITY ............................................................................................... 187 THE JUSTICE SYSTEM ......................................................................................... 225 SPORTS, ARTS AND CULTURE ............................................................................ 231 1 ND 2 National People’s Assembly ORGANISATIONAL CHARACTER AND RE-DESIGN 2 Consolidating the ground -

The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 8-10-2009 Relays in Rebellion: The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer Cathy LaVerne Freeman Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, Cathy LaVerne, "Relays in Rebellion: The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/39 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELAYS IN REBELLION: THE POWER IN LILIAN NGOYI AND FANNIE LOU HAMER by CATHY L. FREEMAN Under the Direction of Michelle Brattain ABSTRACT This thesis compares how Lilian Ngoyi of South Africa and Fannie Lou Hamer of the United States crafted political identities and assumed powerful leadership, respectively, in struggles against racial oppression via the African National Congress and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. The study asserts that Ngoyi and Hamer used alternative sources of personal power which arose from their location in the intersecting social categories of culture, gender and class. These categories challenge traditional disciplinary boundaries and complicate any analysis of political economy, state power relations and black liberation studies which minimize the contributions of women. Also, by analyzing resistance leadership squarely within both African and North American contexts, this thesis answers the call of scholar Patrick Manning for a “homeland and diaspora” model which positions Africa itself within the historiography of transnational academic debates. -

The Neighbouring Mayor of Blouberg, Honourable Pheedi

State of the District Address and Budget Speech by the Executive Mayor of the Capricorn District Municipality His Worship Cllr John Mpe, Mohodi, Molemole 26 May 2017 Madam Speaker, the Programme director Kgoshigadi Manthata and your Council The host Mayor of Molemole municipality, honourable Paya The neighbouring Mayor of Blouberg, honourable Pheedi Lepelle-Nkumpi Mayor, honourable Sibanda Kekana Polokwane Executive Mayor, honourable Nkadimeng the Molemole speaker, Cllr Moreroa and other speaker from our local municipalities Chief-whip of CDM, Cllr Calvin Masoga and Chief-whips of our local municipalities Maapara-Nkwe, Mantona, Bakgoma le bakgomanan Members of the Mayoral Committee Executive committee members All councillors present from all our municipalities Representatives from Provincial Government Representatives from Eskom, RAL, SALGA, Lepelle Northern Water, Old Mutual, all financial institutions, institutions of higher learning Sports Academies and SAFA Capricorn Region My special guests from DEAFSA, Baswa le Meetse, local artists, Dendron High and its own SGB, all schools from Mohodi, Our acting municipal manager, Ms Thuli Shiburi All municipal managers present here Managers and officials from all our municipalities Media fraternity The community in large from all our municipalities, Blouberg, Molemole, Lepelle-Nkumpi and Polokwane Thobela, I am humbled by the opportunity given to me to be with you today here, to come and present the State of the District Address (SODA). The district which is a destiny of choice, an ideally district situated as a stopover, the convergence centre and the heartbeat of Limpopo and the economic nerve centre of our Province. INTRODUCTION This SODA takes place during the year in which one of the key architects of the free and democratic South Africa, Mr Oliver Reginald Tambo, would have turned 100 years old, had he lived. -

These Are the New Street Names That Represent All Racial Groups, Genders and Political Spectrums, Including Afrikaner Religious

These are the new street names that represent all racial groups, genders and political spectrums, including Afrikaner religious leaders and academics that played an important role in the country's liberation struggle. According to the Executive Mayor, Cllr Kgosientso Ramokgopa, the street name changes were necessary to ensure racial harmony and cohesion in the city. Nelson (Madiba) Mandela (1918 - ) Nelson Mandela is one of the most famous political leaders in the world. He was born in Qunu, near Umtata in the Eastern Cape and is a qualified lawyer. He was the first democratically elected South African president, serving from 1994 to 1999. Before his presidency, Mandela was a militant anti-apartheid activist and the leader and co-founder of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC). In 1962, he was arrested and convicted of sabotage and other charges. He was sentenced to life imprisonment, for treason, by the apartheid government but was released in February 1990 after serving 27 years. Professor Johan Heyns (1928 – 1994) Johan Heyns was an influential Afrikaner Calvinist theologian and moderator of the general synod of the Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerk (NGK). He was assassinated at his home in Waterkloof Ridge in 1994. His death drew shock and outrage from all moderates in South Africa, including Nelson Mandela. Heyns was instrumental in the 1986 NGK decision to abandon its support for apartheid and brand it a sin. Although his murder was never officially solved, it is widely believed that it was directly related to his criticism of apartheid. Nelson Mandela paid homage to him as a martyr for his country and a soldier of peace. -

South Africa Tobacco Industry Interference

SOUTH AFRICA TOBACCO INDUSTRY INTERFERENCE INDEX 2019 Acknowledgements Many people contributed to the development of this report. Special thanks to Hana Ross, Nicole Vellios, Samantha Filby, Corné Van Walbeek, Peter Ucko, Olalekan Ayo-Yusuf and Cindy Konar. This report is made possible with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies under the Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products (STOP). We acknowledge Mary Assunta for her technical advice in the preparation of this Index. The information from this report will form part of the Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index, a global survey of how public health policies are protected from the industry’s subversive efforts, and how governments have pushed back against this influence. The tobacco Industry Interference Index was initiated by the South-East Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) as a regional report and with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies' Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products (STOP), is part of a global publication of the Global Centre for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (GGTC) at the School of Global Studies in Thammasat University. For further information contact: Prof Olalekan Ayo-Yusuf Director: African Centre for Tobacco Industry Monitoring and Policy Research (ATIM) Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Molotlegi Street Ga-Rankuwa Pretoria, Gauteng Email: [email protected] Telephone: +27 (0) 12 521 3319 Peter Ucko CEO: TAG Tobacco Alcohol and Gambling Advisory Advocacy and Action Group Email: [email protected] Mobile: +27 82 454 9889 FOREWORD Most industries have skeletons in their closets; the tobacco industry is no exception. In South Africa, and globally, the tobacco industry has a long history of behaving unethically and unlawfully. -

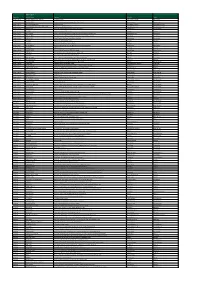

Updated Efuel Site List

eFuel Site List - April 2019 Province Town Merchant Name Oil Company Address 1 Address 2 Telephone EASTERN CAPE ALGOA PARK PE MILLENNIUM CONVENIENCE CENTRE ENGEN CNR UITENHAGE & DYKE ROAD ALGOA PARK 041-4522619 EASTERN CAPE ALICE MAVUSO MOTORS ENGEN 792 MACNAB STREET ALICE 043-7270720 EASTERN CAPE ALIWAL NORTH ALIWAL AUTO VULSTASIE ENGEN 103 SOMERSET STREET ALIWAL NORTH 051-6342622 EASTERN CAPE AMALINDA EL CALTEX AMALINDA CALTEX 29 MAIN ROAD AMALINDA 043-7411930 EASTERN CAPE BEACON BAY EL BONZA BAY CONVENIENCE CENTRE ENGEN 45 BONZA BAY BEACON BAY 043-7483671 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO BHISHO MOTORS SHELL 658 INDEPENDENCE BOULEVARD BHISHO 040-6391785 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO RAITHUSI SERVICE STATION CALTEX 8908 MAITLAND ROAD BHISHO 043-6436001 EASTERN CAPE BHISHO UBUNTU MOTORS ENGEN CNR PHALO & COMGA ROADS BHISHO 040-6392563 EASTERN CAPE BLUEWATER BAY PE BLUE WATER BAY CENTRE ENGEN CNR HILLCREST & WEINRONK WAY BLUEWATER BAY 041-4662125 EASTERN CAPE BURGERSDORP KIMJER MOTORS BURGERSDORP ENGEN 37 PIET RETIEF STREET BURGERSDORP 051-6531835 EASTERN CAPE CENTRAL PE RINK AUTO CENTRE ENGEN 44 RINK STREET CENTRAL 041-5821036 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK OUKOP MOTORS CALTEX 1 MIDDELBURG ROAD OUKOP INDUSTRIAL AREA 048-8811486 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK STATUS DRIVEWAY CRADOCK ENGEN MIDDELBURG ROAD OUKOP INDUSTRIAL AREA 048-8810281 EASTERN CAPE CRADOCK TOTAL CRADOCK (CORPCLO) TOTAL 24 VOORTREKKER STREET CRADOCK 048-8812787 EASTERN CAPE DESPATCH TOTAL DESPATCH TOTAL 78 BOTHA STREET DESPATCH 041-9333338 EASTERN CAPE DUTYWA TOTAL DUTYWA TOTAL RICHARDSON ROAD DUTYWA 047-4891316 -

ALTERNATION Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa Volume 24 Number 1 (2017) Electronic ISSN 1023-1757

ALTERNATION Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa Volume 24 Number 1 (2017) Electronic ISSN 1023-1757 21st Century Geo-political Discourses on India’s Diaspora: Global Perspectives AND Current Trends in Postgraduate Research in the Social Sciences * Alternation is an international journal which publishes interdisciplinary contributions in the fields of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa. * Prior to publication, each publication in Alternation is reviewed by at least two independent peer reviewers. * Alternation is indexed in The Index to South African Periodicals (ISAP) and hosted online on the UKZN platform, on OJS, and by EBSCO * Alternation is published every semester. Special editions may be published p.a. * Alternation was accredited in 1996. EDITOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Johannes A. Smit (UKZN) Nobuhle P. Hlongwa (UKZN) ASSISTANT EDITOR: Denzil Chetty; ASSISTANT EDITOR: Beverly Vencatsamy Alternation Editorial Committee Catherine Addison (UNIZUL); Nyna Amin (UKZN); Urmilla Bob (UKZN); Denzil Chetty (UNISA); Rubby Dhunpath (UKZN); Judith Lütge Coullie (UCanterbury); Brian Fulela (UKZN); Nobuhle Hlongwa (UKZN); Rembrandt Klopper (UKZN/ UNISA); Sadhana Manik (UKZN); Jabulani Mkhize (UFH); Nhlanhla Mkhize (UKZN); Sikhumbuzo Mngadi (UJ); Shane Moran (UFH); Thabo Msibi (UKZN); Maheshvari Naidu (UKZN); Thengani Harold Ngwenya (DUT); Johannes A. Smit (UKZN); Graham Stewart (DUT); Beverley Vencatsamy (UKZN) Alternation Research Board Salim Akojee (Nottingham, UK); Robert Balfour (North-West University, SA); Lesiba Baloyi (Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University, SA); Jaco Beyers (Pretoria, SA); Stephen Bigger (Worcester, SA); Victor M.H. Borden (Indiana, USA); Vivienne Bozalek (UWC, SA); Renato Bulcao de Moraes (Paulista, Brazil); Ezra Chitando (Zimbabwe); Hamish Coates (Melbourne, Aus); Ampie Coetzee (UWC, SA); Scarlett Cornelissen (Stellenbosch, SA); Chats Devroop (UKZN, SA); Simon During (Melbourne, AUS); Farid Esack (UJ, SA); Noel Gough (La Trobe University, Aus); Rosalind I.J. -

Branches-And-Boxers-Open.Pdf

Branch Open Province Branch Name Address Suburb Town Eastern Cape OXFORD STREET EAST LONDON 71 Oxford street East London Central East London Eastern Cape QUEENSTOWN Permanent Building, The Hexagon, 93 Cathcart road Queenstown Queenstown Eastern Cape KING WILLIAMSTOWN 21 Taylor street King William's Town King William's Town Eastern Cape MACLEAN ROAD KING WILLIAMSTOWN shop 1 and 2, 39 Maclean road King William's Town King William's Town Eastern Cape GREENACRES Shop 126, Greenacres Shopping Centre, Ring road Greenacres Port Elizabeth Eastern Cape DUTYWA Jointprop Building, 1 Main road Idutywa Idutywa Eastern Cape MDANTSANE Shop 43 and 44, Mdantsane City Mall, Cnr Qumza Higway and Billie road Mdantsane Unit 4 Mdantsane Eastern Cape PORT ALFRED Shop 6A, 1st Floor, Heritage Mall, Cnr Gluckman road and Biscay road Port Alfred Port Alfred Eastern Cape BEACON BAY Shop 3, Beacon Bay Retail Park, Bonza Bay road Beaconhurst East London Eastern Cape NGCOBO 206 Cnr Church and High street Engcobo Engcobo Eastern Cape CENTANI Old Magistrate Building, Main street Kentani Kentani Eastern Cape BUTTERWORTH Shop 1, Super Spar Centre, Cnr Merriman street and High street Butterworth Butterworth Eastern Cape LUSIKISIKI 169 Main road Lusikisiki Lusikisiki Eastern Cape MOUNT FRERE Shop 10, Mount Frere Mall, 350 Main street Mount Frere Mount Frere Western Cape HOUT BAY Shop E6, Main Stream Shopping Centre, Main road Hout Bay Hout Bay Eastern Cape NGQELENI Cnr King George road and Armstrong street Ngqeleni Ngqeleni Eastern Cape VINCENT PARK Shop 52, Vincent Park -

National Orders Awarded to Deserving Recipients

Recipients of the National Orders 2019 REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA National Orders awarded to deserving recipients On Thursday, 25 April 2019, just two days Order of the Baobab, the Order of Luthuli, before the 25th Freedom Day since the the Order of Mapungubwe, and the Order dawn of freedom and democracy in South of the Companions of OR Tambo – also Africa, President Cyril Ramaphosa bestowed recognise individuals who have made their National Orders to 30 deserving recipients mark in the building of a non-racial, non- at the investiture ceremony held at the sexist, democratic and prosperous South Sefako Makgatho Presidential Guesthouse in Africa, as envisaged in the Constitution of the Pretoria. Republic of South Africa of 1996. National Orders also contribute towards Government has since 2003 been bestowing unity, reconciliation and nation-building in National Orders to deserving citizens and South Africa. eminent foreign nationals who have contributed towards the advancement of democracy and President Ramaphosa, as the Grand Patron of who made a significant impact on improving the National Orders, was assisted by the Director- Mr Jeffrey Tsakale receives the Order of Mendi for Bravery on behalf of lives of South Africans. General in The Presidency, Dr Cassius Lubisi, nine-year-old Thapelo, who drowned on 28 February 2018 after rescuing who is also the Chancellor of National Orders his friend from a waterlogged trench in Soshanguve, north of Pretoria. The six National Orders – the Order of Mendi and the Advisory Council on National Orders, for Bravery, the Order of Ikhamanga, the in bestowing the awards to the recipients.