1 • Ensure the Integrity of Tasmania's GM Moratorium by Changing the Definition of 'Genetically Modified Organism' in Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issues and Decision Memo for Final

A-475-818 A-489-805 Sunset Review - 2018 Public Document AD/CVD Operations VI: DD, SH DATE: November 28, 2018 MEMORANDUM TO: Gary Taverman Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations, performing the non-exclusive functions and duties of the Assistant Secretary for Enforcement and Compliance FROM: James Maeder Associate Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations performing the duties of Deputy Assistant Secretary for Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Operations SUBJECT: Issues and Decision Memorandum for Final Results of the Expedited Fourth Sunset Reviews of the Antidumping Duty Orders on Certain Pasta from Italy and Turkey I. Summary We have analyzed the substantive responses of interested parties in the fourth sunset reviews of the antidumping duty (AD) orders1 covering certain pasta (pasta) from Italy and Turkey. We recommend that you approve the positions described in the “Discussion of the Issues” section of this memorandum. Below is the complete list of the issues in these sunset reviews for which we received substantive responses: 1. Likelihood of continuation or recurrence of dumping; and 2. Magnitude of the margins likely to prevail. II. Background On August 1, 2018, the Department of Commerce (Commerce) published the notice of initiation of the fourth sunset reviews of the Orders, pursuant to section 751(c) of the Tariff Act of 1930, 1 See Notice of Antidumping Duty Order and Amended Final Determination of Sales at Less Than Fair Value: Certain Pasta from Turkey, 61 FR 38545 (July 24, 1996); See Notice of Antidumping Duty Order and Amended Final Determination of Sales at Less Than Fair Value: Certain Pasta from Italy, 61 FR 38547 (July 24, 1996) (collectively, the Orders). -

Navigator Newsletter August 2016

Navigator Newsletter August 2016 Food & Dietary Supplies The Experienced Leader in Group Purchasing • Produce Alliance > A monthly newsletter to keep you informed. • Smucker's > Thank you for being a valued member of Navigator Group Purchasing, Inc. We are the experienced leader in healthcare and hospitality purchasing services offering you Full Transparency Reporting, Vendor Flexibility, and Realized Savings. Medical Products & Services Navigator is your resource for spend management. • ConvaTec > We are here to help you maximize savings • United Lab > opportunities and choice with the industry's top vendors and manufacturers. Our goal is to keep you informed on contract updates and promotions from our preferred vendor partners as well as industry news. Business Products & Services Please contact your Navigator • Phoenix Textile > Account Representative for more information. • Sherwin-Williams > Visit Our Website • Shred-it > Find out how a Navigator membership can work for you. Call us today! 1-800-642-3020 Industry News • Foodbuy Reports: - Member Advantage > - Pricewatch > - Produce Market Advisory > - Inflation Q2 • Upcoming Events PA SERVICES FOOD SAFETY & QUALITY ASSURANCE CENTRAL PROCUREMENT SERVICES At Produce Alliance, food safety and Quality assurance is not Through our 4+ billion network our dedicated & just our management initiative, it is our way of life. From the experienced procurement arm manages price, grower farm to your customer’s plate, our dedication to food safety is contract compliance, Quality & logistics daily. -

Category Slaughterhouse (For Meat and Poultry) / Breaking Location

Supply Chain Disclosure Poultry Upstream Snapshot: December 2018 Published: March 2019 Category Slaughterhouse (for meat and poultry) / Breaking location (for eggs) Location Address Country Chicken Abatedouro Frigorifico Avenida Antonio Ortega nº 3604, Bairro Pinhal , Cabreuva – São Paulo – Brasil Brazil Chicken Agrosul Agroavícola Industrial S.A. Rua Waldomiro Freiberger, 1000 - São Sebastião do Caí, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil Brazil Turkey Agrosuper Chile Condell Sur 411, Quilpué, Valparaiso, Región de Valparaíso, Chile Chile Chicken Agrosuper LTD Camino La Estrella 401, Rancgua, Chile Chile Poultry Animex Foods Sp. z o.o. Sp. k. Morliny Animex Foods Sp. z o.o. Sp. k. Morliny 15, 14-100 Ostróda, Branch of Iława, Poland Poland Chicken Belwood Lowmoor Business Park Kirkby-In-Ashfield, Nottingham NG17 7ER UK Turkey Biegi Foods GmbH Schaberweg 28 61348 Bad Homburg Germany Poultry BODIN LES TERRES DOUCES SAINTE-HERMINE 85210 France Poultry Bodin et Fils ZA Les Terres Douces, Sainte Hermine, France France Chicken BOSCHER VOLAILLES ZA de Guergadic 22530 Mûr de Bretagne France Chicken Boxing County Economic Development Zone Xinsheng Food Co., Ltd. Fuyuan two road, Boxing County Economic Development Zone, Binzhou China Duck Burgaud Parc Activ De La Bloire 42 Rue Gustave Eiffel 85300 France Turkey Butterball - Carthage 411 N Main Street, Carthage, MO 64836 USA Turkey Butterball - Mt. Olive 1628 Garner's Chapel Road, Mt Olive, NC 28365 USA Chicken C Vale - Paloina Av Ariosvaldo Bittencourt, 2000 - Centro - Palotina, PR Brazil Duck Canards d'Auzan -

Cargill Inc. V. WDS Inc

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA CHARLOTTE DIVISION DOCKET NO. 3:16-cv-00848-FDW-DSC CARGILL, INC., and CARGILL MEAT ) SOLUTIONS, CORP., ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) vs. ) ORDER ) WDS, INC., JENNIFER MAIER, and ) BRIAN EWERT, ) ) Defendants. ) ) THIS MATTER is before the Court upon the filing of several post-trial motions by Plaintiffs and Defendants and one pending pre-trial motion filed by Plaintiffs. Before trial, Plaintiffs sought default judgment against all Defendants as sanction for abusive litigation practices. (Doc. No. 187). After trial, Plaintiffs filed a Motion for Award of Prejudgment Interest (Doc. No. 320), a Motion for Award of Attorneys’ Fees and Costs (Doc. No. 325), and a Memorandum of Law on the Unfair and Deceptive Trade Practice Act (Doc. No. 329).1 Defendants WDS, Inc. (“WDS”) and Brian Ewert (“Ewert”) move under Rule 50(b) and Rule 59 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for judgment as a matter of law in its favor or in the alternative a new trial. (Doc. No. 322). Defendant Jennifer Maier (“Maier”) also filed a motion seeking judgment as a matter of law in her favor under Rule 50(b) or in the alternative, a new trial 1 Defendant Jennifer Maier filed a voluntary petition under Chapter 7 of the United States Bankruptcy Code, but the automatic stay has been terminated and modified to allow this case to “proceed in all respects to completion.” (See Doc. No. 346-1). Therefore, the Court can proceed on all motions and matters against all Defendants. (See Doc. Nos. 346, 348). 1 Case 3:16-cv-00848-FDW-DSC Document 366 Filed 03/28/18 Page 1 of 47 or amendment to the judgment under Rule 59. -

Meeting Record Handout

PERD U E (non-"enhanced") B\.S t-: U :~:•. :)) -: '! 1'= S,T E ''-i), Amount'" 110 LG '8 R E ("enhanced") BEST TO US€ OR I"/IUZE BY '\ MAR 2507 7OMoo P-171 American Heart Association ,.% !AeerJ A.meric.Jn "*11 ~ bod .:r leriatl , saltaledfa l anll~ Og 0% .,....1I\'_""',get Iron 4% ottallll'-lfat.....fat. Not.~centlOun:e ~ fiber,"', villmlllA. vllamln c. and Clllclulll. "hIt*It DeItf var_..bUIld01\'2.000 cabtI Hatura'· Chlde.n 8roth IngnHIlenta: ChIcken- Broth. Sa/t, Carrageenan. GLUTEN FREE 'STRIBUTED BY: PILGRIM'S PRIDE CORPORATION PO BOX 93 PJn88URG,TX 7: ... -I I "I ~-- \ ~ ;; \ ~ z -'=- ~ T !lflf~~IJlniWt ................. • $3.52 1 ca......110 Call OfT 'OJ" $1. 9 ,-..J'at2.5g SaturaTed Fat 0.5g TflltS Fatog Pof~nsaturated Fat Og Monounsaturated ~1;_ ':'2t .........,,~. I lail.,8Omg Rlghr Sfore. Rlahr Price f.I~_ ' Og Dietary Fiber Og Ameetcan ,..., $ 'dan SugarsOg" ....._tr__...& IIIPIIIIIaIIp lIroteln-23g 4ft; • ==...-'=-~=:..~==::----..,-"'~ 'lC) AiMCJAt~1H;.Io!y1lQ:SS!o ,.pawb'=:............._.. "IIIliIIl __1'IDIIr1l£1.If OIQlOe"OICIIH VItamIn A0% ~ c.iCiumO% 'PIIn:idtlilfi~ 0IlI0IIe dI8L OIMIIUTBIaY: MOlt =: AI rtJ .....---•......SI"UBIIaF. - .-[..111"\. GiIiII i" ~- "'-.I!i&. ' . What People Are Saying About "Pumped-Up" Poultry: "We want consumers to know what they're getting, said California Poultry Federation President Bill Mattos. We think it's kind of a fraud to sell something in the refrigerated (not frozen) case that looks fresh and feels fresh but contains up to 15 percent water and salt." The Seattle Times September 15, 2004 "Some poultry producers are adding a solution of sodium and water to raw poultry products in order to enhance flavor or increase moisture content. -

Get High on the Wow Factor Page 24 Spring 2015

FOOD FANATICS FOOD FOOD PEOPLE MONEY & SENSE PLUS Regional Chinese Group Dining Fear of Failure I’ll Drink to That! The latest riffs revealed, Cash in on large parties, 7 nightmare busters, Gin is in, page 8 page 38 page 52 page 62 THE WOW FACTOR THE WOW Sharing the Love of Food—Inspiring Business Success SPRING 2015 BLOWN AWAY GET HIGH ON THE WOW FACTOR PAGE 24 SPRING 2015 FOOD Real Chinese Steps Out 8 America’s regional Chinese cuisine gets ADVERTISEMENT back to its roots. In the Raw 14 Tartare goes beyond beef, capers and PAGE 112 egg yolk. Tapping Into Maple Syrup 20 This natural sweetener breaks out of its morning routine. COVER STORY The Wow Factor 24 When the ordinary becomes extraordinary. MAPLE FOOD PEOPLE SYRUP GOES BOTH Bigger Is Better 38 Master a group mentality to cash in on WAYS— large parties. SWEET AND SAVORY Talk Shop PAGE 20 40 Upping the minimum wage: thumbs up or thumbs down? Road Trip to Las Vegas 44 Take a gamble on a restaurant off the strip. PREMIUM QUALITY SIGNATURE TASTE EXCEPTIONAL PERFORMANCE Download the app on iTunes or view the MONEY & SENSE magazine online at FOODFANATICS.COM The Secret to the Upsell 48 A seasoned dining critic says to ditch selling and focus on service. Nightmare Busters 52 Ways to combat 7 of the most common restaurant fears. I’ll Drink to That 62 Gin for the win: The original flavored spirit paves the way for focused beverage programs. WHEN THE TUNA IN TARTARE BECOMES A SNOOZER, GIVE OTHERS A TRY IN EVERY ISSUE (HINT: SALMON) PAGE 14 FOOD Trend Tracker 31 What’s turning up the heat and what’s cooling off. -

Cadenza Document

VGM Club Report Date: Jul 2019 Contracted Manufacturer Report Mfr Name Has Rebate Has Pricing 3M Y Y Abbott Nutrition Y N ACH Food Companies Y N Advance Food Products LLC AFP Y Y AdvancePierre Y Y Agro Farma Inc Y Y Ajinomoto Windsor Inc (formerly Windsor Frozen Foods) Y N Allied Buying Corporation (ABC) Y N All Round Foods Bakery Products Y N Alpha Baking/National Baking Y N American Licorice Co Y N American Metalcraft Y N American Roland Food Corp Y N Amplify Snack Brands Y N Amy's Kitchen Inc Y N Anchor Packaging Y Y Antonio Mozzarella Factory Y N Appetizers And Inc Y Y Apple & Eve Y Y Argo Tea Y Y Arizona Tea - Hornell Brewing Company Y Y Armanino Foods Y Y Armour-Eckrich Meats LLC DBA Carando Y N Armour Eckrich - Smithfield Y Y Ateeco/Mrs T's Pierogies Y Y Atlantic Mills Co Y Y Awake Chocolate Y N Azar Nut Company Y N Bagcraft Packaging LLC Y N Bake N Joy Inc Y N Bakery De France Y Y Ballard Brands Y Y BarFresh Corporation Inc Y Y Barilla America Inc Y Y Basic American Food Co Y Y Bay Valley Foods LLC Y N Belgioioso Cheese Inc Y N Bel Kaukauna Cheese Co Y Y Berks Packing Co Inc Y N Berry Plastics Diet Kits Y N Berry Plastics Liners Y Y Beverage Air Y N Page 1 Of 9 VGM Club Report Date: Jul 2019 Contracted Manufacturer Report Mfr Name Has Rebate Has Pricing Beyond Meat Y Y B&G Foods Inc Y Y Big City Reds /American Foods Y N Big Red Inc Y Y BioSelect N Y Biscomerica Corp. -

Analysis of the Meat Market in Canada

ANALYSIS OF THE MEAT MARKET IN CANADA October 2018 This report is primarily based on data of: IBISWorld, Euromonitor International, Eurostat, United States International Trade Commission – USITC, United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service – USDA FAS/Ottawa, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Statistics Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Production and import from the EU ............................................................................................................... 4 1.1. Pork ........................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Beef ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 1.3. Meat preparations ............................................................................................................................... 13 2. The situation in the industry ........................................................................................................................ 17 2.1. Introduction - characteristics of the market ........................................................................................ 17 2.2. The situation on the meat market in Canada ...................................................................................... 21 2.3. The situation on the market of processed red meat/meat preparations in Canada -

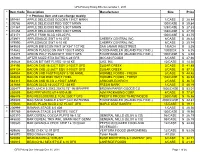

* Item Code Description Manufacturer Size Price * = Produce Item and Can

GFS Primary Pricing Effective October 1, 2011 * Item Code Description Manufacturer Size Price * = Produce item and can change weekly * 597481 APPLE DELICIOUS GOLDEN 138CT MRKN 1/CASE $ 28.84 * 200786 APPLE DELICIOUS RED 100CT MRKN 100/CASE $ 29.84 * 201367 APPLE DELICIOUS RED 125CT MRKN 125/CASE $ 27.83 * 201456 APPLE DELICIOUS RED 138CT MRKN 138/CASE $ 27.70 * 473171 APPLE FRSH SLCD 100-2Z P/L 100/CASE $ 33.75 278971 APPLESAUCE SWT 6-10 GFS CHERRY CENTRAL INC. 6/CASE $ 26.42 179990 APPLESAUCE SWT 6-10 KE CHERRY CENTRAL INC. 6/CASE $ 25.74 549533 APRON BIB ECON WHT 34"X34" 1CT KE SAN JAMAR INDUSTRIES 1/EACH $ 3.35 114642 APRON PLAS ECON WHT 100CT HNDG FOODHANDLER (ISLAND POLY INC.) 100/BOX $ 6.35 116475 APRON POLY PLAIN WHT 100CT GFS FOODHANDLER (ISLAND POLY INC.) 100/CASE $ 8.94 267080 APTZR MOZZ STIX BATRD 6-2# GFS MCCAIN FOODS 6/CASE $ 27.96 293628 BACON BIT IMIT FLVRD 10-1# KE CHS, INC. 10/CASE $ 14.50 314196 BACON CKD 18-22CT EQV 3-100CT GFS SUGAR CREEK 3/CASE $ 41.89 874124 BACON CKD 22-26CT EQV 3-100CT GFS SUGAR CREEK 3/CASE $ 37.13 594954 BACON CKD FAST'N EASY 3-100 HRML HORMEL FOODS - FRESH 3/CASE $ 44.48 433608 BACON CKD RND 192CT HRML HORMEL FOODS - FRESH 192/CASE $ 38.54 563315 BACON CKD SLCD 2-150CT ARMR ARMOUR-ECKRICH 2/CASE $ 36.74 247669 BACON SLCD 18-22CT FZ 15# KE FRESH MARK 1/CASE $ 40.19 330477 BAG LUNCH 5.25X3.25X10.75" 1M BRNPPR BROWN PAPER GOODS CO. -

Cargill Incorporated by Segment

BASE PROSPECTUS May 23, 2012 Cargill, Incorporated (incorporated with limited liability in the State of Delaware, United States of America) U.S.$6,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Program On December 16, 1996, each of Cargill, Incorporated (‘‘Cargill, Inc.’’, ‘‘Cargill’’, the ‘‘Company’’ or the ‘‘Issuer’’), Cargill Global Funding PLC (‘‘Cargill Global’’) and Cargill Asia Pacific Treasury Ltd (‘‘Cargill Asia Pacific’’) entered into a U.S.$1,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Program (the ‘‘Program’’) and issued an offering circular on that date describing the Program. The Program has been updated from time to time and several offering circulars have been issued in connection therewith. This base prospectus (the ‘‘Base Prospectus’’) further updates the Program, supersedes all previous offering circulars and/or base prospectuses and is valid for a period of 12 months as from the date hereof. Any Notes (as defined below) issued under the Program on or after the date of this Base Prospectus are issued subject to the provisions herein. This does not affect any Notes already issued. Under the Program, Cargill, Inc., may from time to time issue notes in bearer form (‘‘Bearer Notes’’) or registered form (‘‘Registered Notes’’ and, together with Bearer Notes, the ‘‘Notes’’) denominated in any currency (including euro) as agreed between Cargill, Inc. and the relevant Dealer (as defined below). Cargill, Inc. will not issue Bearer Notes unless it and any Dealer participating in the issue of such Bearer Notes has received a written opinion of independent legal counsel of recognized standing stating that payments on such Bearer Notes will not be subject to U.S. -

Certain Pasta from Italy and Turkey

Certain Pasta From Italy and Turkey Investigation Nos. 701-TA-365-366 and 731-TA-734-735 (Second Review) Publication 3947 September 2007 Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission COMMISSIONERS Daniel R. Pearson, Chairman Shara L. Aranoff, Vice Chairman Deanna Tanner Okun Charlotte R. Lane Irving A. Williamson Dean A. Pinkert Robert A. Rogowsky Director of Operations Staff assigned Michael Szustakowski, Investigator Christopher Cassise, Investigator Mark Simone, Industry Analyst Steven Trost, Economist David Boyland, Accountant Patrick Gallagher, Attorney Lita David-Harris, Statistician Diane Mazur, Supervisor Investigator Address all communications to Secretary to the Commission United States International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 U.S. International Trade Commission Washington, DC 20436 www.usitc.gov Certain Pasta From Italy and Turkey Investigation Nos. 701-TA-365-366 and 731-TA-734-735 (Second Review) Publication 3947 September 2007 CONTENTS Page Determinations ................................................................. 1 Views of the Commission ......................................................... 3 Part I: Introduction and overview ................................................. I-1 Background .................................................................. I-1 Statutory criteria and organization of the report...................................... I-1 Summary data................................................................ I-3 The original investigations and first five-year reviews................................ -

Foundation News

AMI Foundation News Calendar of Events interactive general sessions by industry experts Foundation News designed to improve your business. Choose A Quarterly Update on Research, Education and Information Worldwide Food Expo from store tours and popular events such as the OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 7 ISSUE 2 When: October 26 – 29, 2005 Product Tasting Reception and the Tech Fair Where: McCormick Place, Chicago, Ill. Luncheon. AMIF BOARD What: Experience a global showcase where more than Contact: For information, contact Marie DeLucia at 202- Rich Armstrong AMIF Releases Co-Sponsored Risk-Based Expert Review of 100 participating countries come to see the latest 587-4228 or [email protected] Sara Lee Food & Beverage Foodborne Listeriosis machinery, products and technologies in action Van Ayvazian Worker Safety, Health and Human Resources Boar’s Head Provision Co., Inc. and remain abreast of critical topics and issues. Great strides have been made in recent years ILSI researchers identified several risk Conference Greg Benedict Over 1,200 exhibitors participate in this show. to reduce the presence of Listeria factors that placed subjects at higher risk for Contact: For more information, go to When: April 9 – 11, 2006 American Foods Group, LLC monocytogenes in consumer food products, contracting listeriosis, primarily individuals www.worldwidefood.com or call 703-934-4700. Where: Hyatt Regency Denver at Colorado Convention Richard L. Bond Center Tyson Foods, Inc. but ongoing efforts to further eliminate the with compromised immune systems, senior Allergen Control Conference What: Leading experts in worker safety will provide J. Patrick Boyle pathogen are needed due to the high citizens and pregnant women.