Jun 2014 MHSM Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 27, 2021 INSIDE This Issue

Established 1947 StagShilo WE WILL MATCH... ADVERTISED PRICES ON ELECTRONICS, CAMERAS, COMPUTERS & MAJOR APPLIANCES. DETAILS ARE AVAILABLE INSTORE OR ONLINE AT WWW.CANEX.CA Your source for Army news in Manitoba Volume 60 Issue 11 Serving Shilo, Sprucewoods & Douglas since 1947 May 27, 2021 INSIDE This Issue Precipitation extinguishes RTA fl ames Page 3 Sgt Rob Nederlof from Base Maintenance leaves for home after work. En route to Wawanesa, he faced a stiff wind coming from the south, but the conditions are only preparing him for his Prairie Thousand adventure this August. Photo Jules Xavier/Shilo Stag Baby sister recalls rela- tionship with Jeff Page 4 Sergeant preparing for Prairie Thousand Jules Xavier years ago. Calgary-born soldier explained. “I am doing Shilo Stag “It was nice when it was done because I this for the mental health of others. The goal could fi nally ride my bike to work,” he re- of this journey is to raise funds and awareness called. “I could fi nally do a decent bike ride.” for Wounded Warriors Canada and the sup- What’s 1,000 kilometres when it comes to Riding in spring, summer and fall, Sgt Ned- port dog program.” going for a bike ride on the prairies? erlof has done the Brandon/Wawawnesa cir- He added, “I have a passion for cycling and For Base Maintenance IC vehicle staffer Sgt cuit using Hwy 2, Hwy 10, Veterans Way and recognized that could be the best way for me Rob Nederlof, this journey west on a 27-speed Hwy 340. Then he did the Melita/Wawanesa to help. -

1994.6400.Cons.Pdf

REPEALED BY THE WINNIPEG ZONING BY-LAW NO. 200/2006 MARCH 1, 2008 CONSOLIDATION UPDATE: DECEMBER 17, 2008 THE CITY OF WINNIPEG WINNIPEG ZONING BY-LAW NO. 6400/94 A Zoning By-law of THE CITY OF WINNIPEG regulating and restricting the use of land and location of buildings and structures in the City of Winnipeg as defined in The City of Winnipeg Act excepting lands governed by the Downtown Winnipeg Zoning By-law No. 4800/88. THE CITY OF WINNIPEG, in Council assembled, enacts as follows: TITLE 1. This By-law may be cited as "The Winnipeg Zoning By-Law". CONTENTS 2. The following PARTS and APPENDIX, titled: PART I - ADMINISTRATION PART II - DEFINITIONS PART III - HOME OCCUPATIONS PART IV - RURAL DISTRICTS PART V - PARKS & RECREATION DISTRICTS PART VI - RESIDENTIAL DISTRICTS PART VII - COMMERCIAL DISTRICTS PART VIII - INDUSTRIAL DISTRICTS PART IX - BOULEVARD PROVENCHER DISTRICT PART X - MOBILE HOME PARK DISTRICT PART XI - ACCESSORY OFF-STREET PARKING AND LOADING PART XII - SIGNS PART XIII - SPECIAL YARD REQUIREMENTS APPENDIX A - ZONING MAPS attached hereto, are hereby adopted as the zoning by-law for the lands shown in APPENDIX "A". By-law No. 6400/94 2 EFFECTIVE DATE 3. This By-law shall come into force and effect on February 1, 1995. DONE AND PASSED in Council assembled, this 26th day of January, 1995. By-law No. 6400/94 3 CONTENTS PART I ADMINISTRATION PART II DEFINITIONS PART III HOME OCCUPATIONS PART IV RURAL DISTRICTS PART V PARKS & RECREATION DISTRICTS PART VI RESIDENTIAL DISTRICTS PART VII COMMERCIAL DISTRICTS PART VIII INDUSTRIAL DISTRICTS PART IX BOULEVARD PROVENCHER DISTRICT PART X MOBILE HOME PARK DISTRICT PART XI ACCESSORY OFF-STREET PARKING AND LOADING PART XII SIGNS PART XIII SPECIAL YARD REQUIREMENTS APPENDIX A ZONING MAPS By-law No. -

The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-39

THE POLICY OF NEGLECT: THE CANADIAN MILITIA IN THE INTERWAR YEARS, 1919-39 ___________________________________________________________ A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board ___________________________________________________________ in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY __________________________________________________________ by Britton Wade MacDonald January, 2009 iii © Copyright 2008 by Britton W. MacDonald iv ABSTRACT The Policy of Neglect: The Canadian Militia in the Interwar Years, 1919-1939 Britton W. MacDonald Doctor of Philosophy Temple University, 2008 Dr. Gregory J. W. Urwin The Canadian Militia, since its beginning, has been underfunded and under-supported by the government, no matter which political party was in power. This trend continued throughout the interwar years of 1919 to 1939. During these years, the Militia’s members had to improvise a great deal of the time in their efforts to attain military effectiveness. This included much of their training, which they often funded with their own pay. They created their own training apparatuses, such as mock tanks, so that their preparations had a hint of realism. Officers designed interesting and unique exercises to challenge their personnel. All these actions helped create esprit de corps in the Militia, particularly the half composed of citizen soldiers, the Non- Permanent Active Militia. The regulars, the Permanent Active Militia (or Permanent Force), also relied on their own efforts to improve themselves as soldiers. They found intellectual nourishment in an excellent service journal, the Canadian Defence Quarterly, and British schools. The Militia learned to endure in these years because of all the trials its members faced. The interwar years are important for their impact on how the Canadian Army (as it was known after 1940) would fight the Second World War. -

A Brief Account of the University of Saskatchewan Contingent, Canadian Officers Training Corps

A Brief Account of the University of Saskatchewan Contingent, Canadian Officers Training Corps By D. F. Robertson VE Day in Europe was 8 May 1945, some sixty years ago. Fighting against Japan continued until the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 8 and 9 August with the official surrender on VJ Day shortly thereafter. On 1 September 1945 the Canadian element of the newly formed Pacific Force was disbanded. One of the more immediate results of all this meant the release from the three services, by one calculation, of some 495,000 personnel. While many returned to their previous occupations a very large number, estimated at 150,000,1 took advantage of government sponsored education in Canadian universities. Former President W. P. Thompson, in The University of Saskatchewan, A Personal History, pointed out that the first of these, “air crew and those who had been wounded, sick or disabled,” began to return to the University of Saskatchewan in 1943. By 1946 there were more than 2,500 and by 1951 most had either finished their course or had left for other reasons.2 But this was not the first encounter of the university with military life. The story really began during the Great War with the formation of the University of Saskatchewan Contingent of the Canadian Officers Training Corps in December 1915. There had been a form of military training, apparently largely drill and marching, carried out in the earlier days of the war. However with the official formation under the command of C. J. Mackenzie, a civil engineer who became Dean many years later, the unit found itself “the most gratuitous of military formations – a draft finding unit – and so the Saskatchewan men reinforced the McGill University Contingent, the Princess Pats and the 28th Battalion.”3 These are the words of President J. -

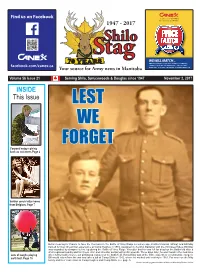

INSIDE This Issue LEST WE FORGET Corporal Enjoys Giving Back As Volunteer

Find us on Facebook 1947 - 2017 StagShilo WE WILL MATCH... ADVERTISED PRICES ON ELECTRONICS, CAMERAS, facebook.com/canex.ca COMPUTERS & MAJOR APPLIANCES. DETAILS ARE Your source for Army news in Manitoba AVAILABLE INSTORE OR ONLINE AT WWW.CANEX.CA Volume 56 Issue 21 Serving Shilo, Sprucewoods & Douglas since 1947 November 2, 2017 INSIDE This Issue LEST WE FORGET Corporal enjoys giving back as volunteer. Page 2 Soldier sends letter home from Belgium. Page 7 Before leaving for France to face the Germans in the Battle of Vimy Ridge a century ago, brothers Harold (sitting) and Bill May trained for their Great War experience at Camp Hughes in 1916. Assigned to the 61st Battalion with the Winnipeg Rifl es, Bill May was wounded by shrapnel to the leg during the Battle of Vimy Ridge. His older brother was left for dead on the battlefi eld after a shell exploded nearby and his cheek, chin and shoulder sustained horrifi c wounds. Three days later, he was found in the mud alive Lots of laughs playing when fellow soldiers were out picking up corpses on the battlefi eld. Harold May was of the fi rst recipients of reconstructive surgery. earth ball. Page 10 Bill would return from the war and take a job at Camp Shilo in 1942, where he worked until retiring in 1961. For more on the May family and their connection to Camp Hughes and Camp Shilo, see page 6. Photos courtesy grandchildren Kathleen Mowbray/Kelvin Schrot 2 Shilo Stag November 2, 2017 Corporal enjoys giving back by volunteering Sarah Francis natural position for her. -

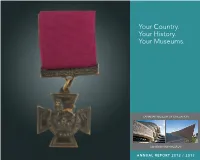

Annual Report 2017-2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017–2018 LEGACIES OF CONFEDERATION EXHIBITION EXPLORED CANADA 150 WITH A NEW LENS N THE OCCASION OF THE 150th ANNIVERSARY OF CONFEDERATION, the Manitoba OMuseum created a year-long exhibition that explored how Confederation has aff ected Manitoba since 1867. Legacies of Confederation: A New Look at Manitoba History featured some of the Museum’s fi nest artifacts and specimens, as well as some loaned items. The topics of resistance, Treaty making, subjugation, All seven Museum Curators representing both and resurgence experienced by the Indigenous natural and human history worked collaboratively peoples of Manitoba were explored in relation to on this exhibition. The development of Legacies of Confederation. Mass immigration to the province Confederation also functioned as a pilot exhibition after the Treaties were signed resulted in massive for the Bringing Our Stories Forward Capital political and economic changes and Manitoba has Renewal Project. Many of the themes, artifacts and been a province of immigration and diversity ever specimens found in Legacies of Confederation are since. Agricultural settlement in southern Manitoba being considered for the renewed galleries as part after Confederation transformed the ecology of of the Bringing Our Stories Forward Project. the region. The loss of wildlife and prairie landscapes in Manitoba has resulted in ongoing conservation eff orts led by the federal and provincial governments since the 1910s. FRONT COVER: Louis Riel, the Wandering Statesman Louis Riel was a leading fi gure in the Provisional Government of 1870, which took control of Manitoba and led negotiations with Canada concerning entrance into Confederation. Photo courtesy of Library and Archives Canada /C-006688d 1867 Confederation Medal The symbolism of this medal indicates that the relationship between the Dominion of Canada and the British Empire was based on resource exploitation. -

The Charles R. Bronfman Foundation's Construction of the Canadian Identity

The Heritage Minutes: The Charles R. Bronfman Foundation's Construction of the Canadian Identity NuaIa Lawlor The Graduate Program in Communications McGiIl University Montreal, Quebec June 1999 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillrnent of the degree of Master of Arts Copyright (c) Nuda Lawlor National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 OfCmada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa Oh: K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Vorre reference Our cYe Nom référence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/fïlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Table of Contents Abstract/ Résumé , . - . ,. - - . - . - . - . - . - . Acknowledgments ........................................... 1. Introduction: The Nation - A Canadian Problem - . - . II. Chapter One: Constructing Canadian Nationalism . - . - . Table 1 Herirage Minutes: Categorical Divisions according to CRB . Table 2 Context/Authenticity for the First Series of Heriiage Minutes. -

1919-1939. – 47 Cm of Photographs

P50 Between the wars photo collection. - 1919-1939. – 47 cm of photographs. This collection consists of photographs of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) activities from its reorganization as a permanent peacetime battalion in March 1919 until its departure for Europe on December 17, 1939. Reproduction or publication of the images requires permission of PPCLI Regimental Museum and Archives. Portraits of individual members of PPCLI are located in P400. Additions to the collection are expected. PPCLI Hockey Team with Capt W.G. “Shorty” Colquhoun, Osborne Barracks, Winnipeg, ca. 1925 Box 1: 50(1)-1 University of Toronto Lacrosse Team. –1920. – R. Bastedo, W.F. McLean, J.C. McClelland, L.N. Ryan, T.R. Anderson, B. Bastedo, H.E. Firth, F.A. Wilcox, G.H McKee, W.A. Dafoe, N.J, Taylor, G.G.E. Raley, F.D. McClure. P50(2)-1 Princess Pats’ Club Dance, Ottawa, Ontario. – 1920. P50(3)-1 [Number not used]. P50(4)-1 [Number not used]. P50(5.1)-1 Tuxedo Barracks: interior view of barrack room. – 1922. P30 PPCLI Between the Wars photo collection Page 1 P50(5.2)-1 Tuxedo Barracks: interior view of barrack room. – 1922. P50(6)-1 Tuxedo Barracks: presentation of Colours by Lord Byng. – 1922. P50(7)-1 [Number not used]. P50(8)-1 Winner of Garrison Cup, Fort Osborne Barracks. –1923. P50(9)-1 [Number not used]. P50(10)-1 PPCLI R.R.A. 1924 / Campbell’s Winnipeg. – 1924 – LCol. C.R.E. Willets, OC; Capt. W.G. Colquhoun, Captain of Association; Lt. R.L. Mitchell, Secretary. R.R.A. -

Fact Sheet # 59 Published By: the Friends of the Canadian War Museum

CAMP HUGHES Page 1 of 3 Researched and Written by: Capt (N) (Ret’d) M. Braham Edited by: Carole Koch avenued area close to the main camp Introduction: Camp Hughes was a formed a lively commercial midway. Canadian military training camp, located in the Rural Municipality of North Cypress, In 1916, the camp trained 27,754 troops, west of the town of Carberry, in Manitoba. making it the largest community in It was actively used for Army training Manitoba outside of Winnipeg. from 1909 to 1934 and as a Construction reached its zenith, and the communications station from the early camp boasted six movie theatres, 1960s until 1991. numerous retail stores, a hospital, a large heated in-ground swimming pool, History: The need for a central training Ordnance and Service Corps buildings, camp in Military District 10 (Manitoba and photo studios, a post office, a prison and NW Ontario) resulted in the establishment many other structures. The troops were of Sewell Camp in 1910, on Crown and accommodated in neat groups of white Hudson's Bay Company land near bell tents, located around the central Carberry, Manitoba. The site was camp. accessible by both the Canadian Northern and Canadian Pacific Railways and the ground was deemed suitable for the training of artillery, cavalry and infantry units. It started out as a city of tents and covered a large area. The name of the camp was changed in 1915 to "Camp Hughes" in honour of Major-General Sir Sam Hughes, Canada's Minister of Militia Main Street, Camp Hughes and Defence at the time. -

Pro Valore, La Croix De Victoria Canadienne, 8 Mai 2008

la Croix de Victoria canadienne Édition révisée Pro Valore : la Croix de Victoria canadienne 1 Pour obtenir de plus amples renseignements, veuillez communiquer avec les organisations suivantes : Direction – Histoire et patrimoine Quartier général de la Défense nationale 101, promenade du Colonel-By Ottawa ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca (télécopieur) 1-613-990-8579 Direction – Distinctions honorifiques et reconnaissance Quartier général de la Défense nationale 101, promenade du Colonel-By Ottawa ON K1A 0K2 www.forces.gc.ca 1-877-741-8332 La Chancellerie des distinctions honorifiques Bureau du secrétaire du gouverneur général Rideau Hall 1, promenade Sussex Ottawa ON K1A 0A1 www.gg.ca 1-800-465-6890 Auteur : Ken Reynolds Direction artistique SMA(AP) DPSAP CS08-0575 Avant-propos Bienvenue à cette édition révisée de la brochure intitulée PRO VALORE : LA CROIX DE VI C TORIA C ANADIENNE , qui donne un aperçu de la création de la nouvelle Croix de Victoria et de l’histoire de cette décoration au sein des forces armées du Canada. L’édition originale ayant reçu un accueil extrêmement favorable, nous avons décidé de publier une version révisée et légèrement plus longue de la brochure. En tant que plus haute décoration de vaillance militaire dans les forces armées du Canada, la Croix de Victoria a une longue et illustre histoire. Qu’il s’agisse des 81 Croix de Victoria britanniques décernées à des militaires canadiens ou de la création et de la production de la Croix de Victoria canadienne, le sujet compte de nombreux aspects fascinants. Pro Valore : la Croix de Victoria canadienne 5 La présente brochure est étroitement liée à de nombreux éléments additionnels se trouvant sur le site Web de la Direction – Histoire et patrimoine (www.forces.gc.ca), notamment toutes les citations complètes tirées de la London Gazette, ainsi que des images et des notices biographiques pour chaque récipiendaire. -

Passchendaele Remembered

1917-2017 PASSCHENDAELE REMEMBERED CE AR NT W E T N A A E R R Y G THE JOURNAL OF THE WESTERN FRONT ASSOCIATION FOUNDED 1980 JUNE/JULY 2017 NUMBER 109 2 014-2018 www.westernfrontassociation.com With one of the UK’s most established and highly-regarded departments of War Studies, the University of Wolverhampton is recruiting for its part-time, campus based MA in the History of Britain and the First World War. With an emphasis on high-quality teaching in a friendly and supportive environment, the course is taught by an international team of critically-acclaimed historians, led by WFA Vice-President Professor Gary Sheffield and including WFA President Professor Peter Simkins; WFA Vice-President Professor John Bourne; Professor Stephen Badsey; Dr Spencer Jones; and Professor John Buckley. This is the strongest cluster of scholars specialising in the military history of the First World War to be found in any conventional UK university. The MA is broadly-based with study of the Western Front its core. Other theatres such as Gallipoli and Palestine are also covered, as is strategy, the War at Sea, the War in the Air and the Home Front. We also offer the following part-time MAs in: • Second World War Studies: Conflict, Societies, Holocaust (campus based) • Military History by distance learning (fully-online) For more information, please visit: www.wlv.ac.uk/pghistory Call +44 (0)1902 321 081 Email: [email protected] Postgraduate loans and loyalty discounts may also be available. If you would like to arrange an informal discussion about the MA in the History of Britain and the First World War, please email the Course Leader, Professor Gary Sheffield: [email protected] Do you collect WW1 Crested China? The Western Front Association (Durham Branch) 1917-2017 First World War Centenary Conference & Exhibition Saturday 14 October 2017 Cornerstones, Chester-le-Street Methodist Church, North Burns, Chester-le-Street DH3 3TF 09:30-16:30 (doors open 09:00) Tickets £25 (includes tea/coffee, buffet lunch) Tel No. -

Cmcc Cmcc 15

Your Country. Your History. Your Museums. CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION CANADIAN WAR MUSEUM annual report 2012 / 2013 ii Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation Information and Services: 819-776-7000/1-800-555-5621 Teletype (TTY): 819-776-7003 Group Reservations: 819-776-7014 100 Laurier Street, Gatineau, QC K1A 0M8 Facility Rentals: 819-776-7018 www.civilization.ca Membership: 819-776-7100 Volunteers: 819-776-7011 Financial Support for the Corporation: 819-776-7016 Publications: 819-776-8387 Cyberboutique: cyberboutique.civilization.ca Friends of the Canadian War Museum: 819-776-8618 1 Vimy Place, Ottawa, ON K1A 0M8 www.warmuseum.ca Image on cover: Victoria Cross medal awarded to Company Sergeant-Major Frederick William Hall Bill Kent CWM20110146 Cat. no. NM20-1/2013 ISSN 1495-1886 © 2013 Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation 1 table of Contents Message from the Chair ................................................................................................................... 2 Message from the President and CEO............................................................................................. 4 THE CORPORATION........................................................................................................................ 8 The Canadian Museum of Civilization....................................................................................... 9 The Canadian War Museum...................................................................................................... 9 The Virtual Museum of New France.........................................................................................