Revised Arraneyn Beeal-Arrish Vannin PDF for CD 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manx Gaelic and Physics, a Personal Journey, by Brian Stowell

keynote address Editors’ note: This is the text of a keynote address delivered at the 2011 NAACLT conference held in Douglas on The Isle of Man. Manx Gaelic and physics, a personal journey Brian Stowell. Doolish, Mee Boaldyn 2011 At the age of sixteen at the beginning of 1953, I became very much aware of the Manx language, Manx Gaelic, and the desperate situation it was in then. I was born of Manx parents and brought up in Douglas in the Isle of Man, but, like most other Manx people then, I was only dimly aware that we had our own language. All that changed when, on New Year’s Day 1953, I picked up a Manx newspaper that was in the house and read an article about Douglas Fargher. He was expressing a passionate view that the Manx language had to be saved – he couldn’t understand how Manx people were so dismissive of their own language and ignorant about it. This article had a dra- matic effect on me – I can say it changed my life. I knew straight off somehow that I had to learn Manx. In 1953, I was a pupil at Douglas High School for Boys, with just over two years to go before I possibly left school and went to England to go to uni- versity. There was no university in the Isle of Man - there still isn’t, although things are progressing in that direction now. Amazingly, up until 1992, there 111 JCLL 2010/2011 Stowell was no formal, official teaching of Manx in schools in the Isle of Man. -

Culture Which Is As Evident Today As It Was 1,000’S of Years Ago

C U LT U R E The Isle of Man has a unique and varied culture which is as evident today as it was 1,000’s of years ago. Uncover the amazing history and heritage of the Island by following the ‘Story of Mann’ trail, whilst taking in some of the Island’s unique arts, folklore and cuisine along the way. THE STORY OF MANN Manx National Heritage reveals 10,000 years of Isle of Man history through the award-winning Story of Mann - a themed trail of presentations and attractions which takes you all over the Island. Start off by visiting the award-winning Manx Museum in Douglas for an overview and introduction to the trail before choosing your preferred destinations. Attractions on the trail include: Castle Rushen, Castletown. One of Europe’s best-preserved medieval castles, dating from the 12th Century. Detailed displays authentically recreate castle life as it was for the Kings and Lords of Mann. Cregneash Folk Village, near Port St Mary. Life as it was for 19th century crofters is authentically reproduced in this living museum of thatched whitewashed cottages and working farm. Great Laxey Wheel and Mines Trail, Laxey. The ‘Lady Isabella’ water wheel is the largest water wheel still operating in the world today. Built in 1854 to pump water from the mines, it is an important part of the Island’s once-thriving mining heritage. The old mines railway has now been restored. House of Mannanan, Peel. An interactive, state of the art heritage centre showing how the early Manx Celts and Viking settlers shaped the Island’s history. -

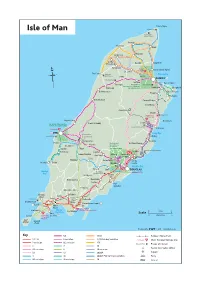

Isle of Man Bus Map.Ai

Point of Ayre Isle of Man Lighthouse Point of Ayre Visitor Centre Smeale The Lhen Bride Andreas Jurby East Jurby Regaby Dog Mills Threshold Sandygate Grove Grand Island Hotel St. Judes Museum The Cronk Ballaugh Ramsey Bay Old Church Garey Sulby RAMSEY Wildlife Park Lezayre Port e Vullen Curraghs For details of Albert Tower bus services in Ramsey, Ballaugh see separate map Lewaigue Maughold Bishopscourt Dreemskerry Hibernia Ballajora Kirk Michael Corony Bridge Glen Mona SNAEFELL Dhoon Laxey Wheel Dhoon Glen & Mines Trail Knocksharry Ballaragh Laxey For details of bus services Cronk-y-Voddy in Peel, see separate map Laxey Woollen Mills Old Laxey Peel Castle PEEL Laxey Bay Tynwald Mills Corrins Folly Tynwald Hill Ballabeg Ballacraine Baldrine Patrick For details of Halfway House Greeba bus services St. John’s in Douglas, Gordon Hope see separate map Groudle Glen and Railway Glenmaye Crosby Onchan Lower Foxdale Strang Governors Glen Vine Bridge Eairy Foxdale Union Mills Derby Niarbyl Dalby Braddan Castle NSC Douglas Bay Braaid Cooil DOUGLAS Niarbyl Rest Home Bay for Old Horses St. Mark’s Quines Hill Ballamodha Newtown Santon Port Soderick Orrisdale Silverdale Glen Bradda Ballabeg West Colby Level Cross Milners Tower Four Ballasalla Bradda Head Ways Ronaldsway Airport Port Erin Shore Hotel Castle Rushen Cregneash Bay ny The Old Grammar School Carrickey Castletown 03miles Port Scale Sound Cregneash St. Mary 05kilometres Village Folk Museum Calf Spanish of Man Head Produced by 1.9.10 www.fwt.co.uk Key 5/6 17/18 Railway / Horse Tram 1,11,12 6 variation 17/18 Sunday variation Peel Castle Manx National Heritage Site 2 variation 6C variation 17B Tynwald Mills Places of interest 3 7 19 Tourist Information Office 3A variation 8 19 variation X3 13 20/20A Airport 4 16 20/20A Point of Ayre variation Ferry 4A variation 16 variation 29 Seacat. -

Guidelines for the Selection of Biological Areas of Special Scientific Interest (Assis) on the Isle of Man

Guidelines for the selection of biological Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSIs) on the Isle of Man Volume 1: Background, guiding principles and Priority Sites Criteria Guidelines for the selection of biological Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSIs) on the Isle of Man This document sets out the background, rationale, guiding principles and minimum criteria for the selection of Areas of Special Scientific Interest (ASSIs) on the Isle of Man. It is one of a series of documents intended to provide a sound scientific basis for the selection of legally protected areas on and around the Island. The Wildlife Act 1990 provides the basis for the designation of ASSIs on the Isle of Man. Reasons for designation may include terrestrial, marine or geological importance of a site, or a combination of features. Please note that the criteria detailed in this document are for the selection of land-based ASSIs for biological reasons. These may include coastal and intertidal zones down to the astronomical low tide limit, but the selection of strictly Marine Nature Reserves is covered by a separate, companion document. Criteria for ASSIs selected primarily for their earth science importance (geological and physiographical features) will also be treated separately. An ASSI may contain a mix of features of importance from any or all of the above categories, which often occur in association. In such cases, more than one set of criteria may be applicable. The purpose of the ASSI system is to safeguard a series of sites which are individually of high natural heritage importance and which collectively represent the diversity of habitats, species and geological and geomorphological features on the Isle of Man. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

T Y N W A L D C O U R T O F F I C I A L R E P O R T R E C O R T Y S O I K O I L Q U A I Y L T I N V A A L P R O C E E D I N G S D A A L T Y N HANSARD Douglas, Tuesday, 17th September 2019 All published Official Reports can be found on the Tynwald website: www.tynwald.org.im/business/hansard Supplementary material provided subsequent to a sitting is also published to the website as a Hansard Appendix. Reports, maps and other documents referred to in the course of debates may be consulted on application to the Tynwald Library or the Clerk of Tynwald’s Office. Volume 136, No. 19 ISSN 1742-2256 Published by the Office of the Clerk of Tynwald, Legislative Buildings, Finch Road, Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 3PW. © High Court of Tynwald, 2019 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 PAGE LEFT DELIBERATELY BLANK ________________________________________________________________________ 2092 T136 TYNWALD COURT, TUESDAY, 17th SEPTEMBER 2019 Business transacted Questions for Written Answer .......................................................................................... 2097 1. Zero Hours Contract Committee recommendations – CoMin approval; progress; laying update report ........................................................................................................... 2097 2. GDPR breaches – Complaints and appeals made and upheld ........................................ 2098 3. No-deal Brexit – Updating guide for residents before 31st October 2019 ..................... 2098 4. No-deal Brexit – Food supply contingency plans; publishing CoMin paper.................... 2098 5. Tax returns – Number submitted April, May and June 2018; details of refunds ............ 2099 6. Common Purse Agreement – Consideration of abrogation ........................................... -

Language Ideologies in Corpus Development for Revived Manx

Studia Celtica Posnaniensia, Vol 2 (1), 2017 doi: 10.1515/scp-2017-0006 SCHOLARSHIP AND LANGUAGE REVIVAL: LANGUAGE IDEOLOGIES IN CORPUS DEVELOPMENT FOR REVIVED MANX CHRISTOPHER LEWIN University of Edinburgh ABSTRACT In this article the role of different ideological viewpoints concerning corpus development within the Manx revival movement in the second half of the twentieth century is explored. In particular, the work of two prominent figures is examined: the Celtic scholar Robert L. Thomson, who published extensively especially on Manx language and literature, and also contributed to the revival, particularly as editor of several pedagogical resources and as a member of the translation committee Coonceil ny Gaelgey, and Douglas Fargher, a tireless activist and compiler of an English-Manx Dictionary (1979). Broadly speaking, Thomson was of a more preservationist bent, cautious in adapting the native resources of the language and wary of straying too far from attested usage of the traditional language, while Fargher was more radical and open especially to borrowing from Irish and Scottish sources. Both were concerned, in somewhat different ways, to remove perceived impurities or corruptions from the language, and were influenced by the assumptions of existing scholarship. A close reading of the work of these scholar-activists sheds light on the tensions within the revival movement regarding its response to the trauma of language death and the questions of legitimacy and authenticity in the revived variety. Particular space is devoted to an analysis of the preface of Fargher’s dictionary, as well as certain features of the body of the work itself, since this volume is probably the most widely consulted guide to the use of the language today. -

Publicindex Latest-19221.Pdf

ALPHABETICAL INDEX OF CHARITIES Registered in the Isle of Man under the Charities Registration and Regulation Act 2019 No. Charity Objects Correspondence address Email address Website Date Registered To advance the protection of the environment by encouraging innovation as to methods of safe disposal of plastics and as to 29-31 Athol Street, Douglas, Isle 1269 A LIFE LESS PLASTIC reduction in their use; by raising public awareness of the [email protected] www.alifelessplastic.org 08 Jan 2019 of Man, IM1 1LB environmental impact of plastics; and by doing anything ancillary to or similar to the above. To raise money to provide financial assistance for parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man whose finances determine they are unable to pay costs themselves. The financial assistance given will be to provide full/part payment towards travel and accommodation costs to and from UK hospitals, purchase of items to help with physical/mental wellbeing and care in the home, Belmont, Maine Road, Port Erin, 1114 A LITTLE PIECE OF HOPE headstones, plaques and funeral costs for children and gestational [email protected] 29 Oct 2012 Isle of Man, IM9 6LQ aged to 16 years. For young adults aged 16-21 years who are supported by their parents with no necessary health/life insurance in place, financial assistance will also be looked at under the same rules. To provide a free service to parents/guardians resident on the Isle of Man helping with funeral arrangements of deceased children To help physically or mentally handicapped children or young Department of Education, 560 A W CLAGUE DECD persons whose needs are made known to the Isle of Man Hamilton House, Peel Road, 1992 Department of Education Douglas, Isle of Man, IM1 5EZ Particularly for the purpose of abandoned and orphaned children of Romania. -

Tynwald 20 Mar 2012 the Chief Minister: No, Thank You

Manx Heritage Foundation Members approved 8. The Chief Minister to move: That in accordance with section 1(2) of the Manx Heritage Foundation Act 1982, Tynwald approves the appointment of the following persons as members of the Manx Heritage Foundation – Miss Patricia Skillicorn Mr Liam O’Neill Dr Brian Stowell The Deputy President: We turn now to Item 8, Manx Heritage Foundation. I call on the Chief Minister to move. The Chief Minister (Mr Bell): Mr Deputy President, the Council of Ministers is pleased to nominate Miss Patricia Skillicorn, Mr Liam O’Neill and Dr Brian Stowell for appointment as lay members of the Manx Heritage Foundation. As Hon. Members will be aware from the information circulated regarding these appointments, the individuals proposed by Council have extensive experience and skills relevant to the work of the Foundation and were selected following an open and transparent public appointment recruitment process. The Manx Heritage Foundation Act requires the Foundation, amongst other things, to promote and assist in the permanent preservation of the cultural heritage of the Island. Miss Skillicorn and Dr Stowell are previous lay members of the Foundation and Council are pleased to propose that they are appointed to the Foundation for another term. Dr Stowell will be well-known to Hon. Members through his pioneering and tireless work to promote the teaching and use of Manx language. This includes writing Manx language courses and presenting programmes on Manx Radio. Miss Skillicorn is a leading figure in local historical circles, being a lecturer to students on the MA course in Manx Studies, participating in research programmes on the Island’s experience in World War I and a published author of titles mixing social history and memoires. -

Area Plan for the East: Draft Plan Site Identification Report

Area Plan for the East: Draft Plan Site Identification Report 25th May 2018 Evidence Paper No. DP EP2 Cabinet Office Contents Page No. 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of this Report 1 Key Findings 1 Strategic Policy Context 1 2. Call for Sites 3 3. Site Coding and Mapping 4 Coding Errors and Corrections 4 4. Identifying Additional Sites to those mapped and coded during the Call for Sites 6 Exercise Sources 6 Call for Sites General Correspondence 6 Evidence Papers 7 Additional Desk Based Research 9 Site Visits 9 Preliminary Publicity 9 5. Categorising Potential Development Sites 10 Category 1 Sites 10 Category 2 Sites 10 Groups of Houses in the Countryside 11 Appendices 1. All Sites Table 12 2. Sites from Submissions 30 3. RLA Sites 33 4. Central Douglas Masterplan 39 5. Employment Sites 40 6. Site Visits 46 1. Introduction Purpose of this report 1.1 This report forms part of the Evidence Base for the Area Plan for the East. It summarises the results of the Call for Sites exercise and explains how a process of identifying additional sites has been undertaken, including additional sites identified through the Preliminary Publicity process. The report goes on to outline which sites qualify for assessment through the Site Assessment Framework (SAF). Such qualification is dependent on a reasoned judgement which splits the long list of sites into the following categories: Category 1 - Sites which do not need to be assessed through the SAF and which can be subsumed within land use designations which reflect the surrounding areas; and Category 2 - Sites which do need to be assessed through the SAF i.e. -

A Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool

e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies Volume 2 Cultural Survival Article 4 5-8-2006 Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, History Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Linguistics Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Maddrell, Breesha (2006) "Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals," e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies: Vol. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol2/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact open- [email protected]. Of Demolition and Reconstruction: a Comparative Reading of Manx Cultural Revivals Breesha Maddrell, Centre for Manx Studies, University of Liverpool Abstract This paper accesses Manx cultural survival by examining the work of one of the most controversial of Manx cultural figures, Mona Douglas, alongside one of the most well loved, T.E. Brown. It uses the literature in the Isle of Man over the period 1880-1980 as a means of identifying attitudes toward two successive waves of cultural survival and revival. Through a reading of Brown's Prologue to the first series of Fo'c's'le Yarns, 'Spes Altera', "another hope", 1896, and Douglas' 'The Tholtan' – which formed part of her last collection of poetry, Island Magic, published in 1956 – the differing nationalist and revivalist roles of the two authors are revealed. -

Isle of Man Family History Society * * * INDEX * * * IOMFHS JOURNALS

Isle of Man Family History Society AN M F O y t E e L i c S I o S y r to is H Family * * * INDEX * * * IOMFHS JOURNALS Volumes 29 - 38 January 2007 - November 2016 The Index is in four sections Indexed by Names - pages 1 to 14 Places - pages 15 to 22 Photographs - pages 23 to 44 Topics - pages 45 to 78 Compiled by Susan J Muir Registered Charity No. 680 IOM FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY JOURNALS INDEX FEBRUARY 2007 to NOVEMBER 2016 1. NAMES FAMILY NAME & FIRST NAME(S) PLACE YEAR No. PAGE Acheson Walter Douglas 2014 1 16 Allen Robert Elliott Bellevue 2015 1 15 Anderson Wilfred Castletown 2014 1 16 Annim William Jurby 2015 2 82 Ansdel Joan Ballaugh 2010 4 174 Atkinson Jonathan Santon 2012 4 160 Banks (Kermode) William Peel 2009 1 43 Bannan William Onchan 2014 2 64 Bannister Molly Sulby 2009 2 87 Bates William Henry Douglas 2014 1 16 Baume Pierre Jean H. J. Douglas 2008 2 80 Beard Ann Isle of Man 2012 1 40 Bell Ann Castletown 2012 1 36 Bell Frank Douglas 2007 3 119 Birch Emily Rushen 2016 2 74 Bishop Edward Kirk Michael 2013 2 61 Black Harry Douglas 2014 1 16 Black James IoM 2015 2 56 Black Stanley Douglas 2014 1 16 Blackburn Benny Douglas 2008 1 19 Boyde Eliza Ballaugh 2010 3 143 Boyde Simon Malew 2013 3 136 Bradford James W. Ramsey 2014 1 16 Bradshaw Clara Jane Ballaugh 2014 1 15 Braid Thomas IoM 2015 2 56 Braide William Braddan 2014 1 32 Breary William Arthur Douglas 2009 4 174 Brew Caesar Rushen 2014 3 108 Brew John Manx Church Magazine 1899 2007 3 123 Brew John Douglas 2012 1 5 Brew Robert Santan 2016 3 139 Brice James Douglas 2014 3 123 Brideson -

Brochure & Price List

KENSINGTON PLACE ONCHAN, ISLE OF MAN ONLY 1 REMAINING Brochure & Price List Superior two bedroom luxury apartments in a unique coastal locationwww.hartford.im Price £295,999 Need help Back-Stop Part Rent Smooth Part Exchange Exchange to Buy Move to buy? The missing link between owning your new home Own 100% now, pay 20% later Investing in your future Sell your home without the stress Visit hartford.im or call 631000 Award-winning properties in stunning Island-wide locations. Superior build quality and the finest interior fittings. Homebuyer support packages and unrivalled after sales service. Apartments, penthouse suites, first time buyer homes, family homes and luxury super-mansions. Welcome to Hartford Homes. Welcome to www.hartford.im Hartford Homes We call it the Hartford Difference. It’s a complete peace of mind. For the first two years our combination of business ethics, industry warranty covers fixings and finishings, and in years expertise and a deep understanding of 2-10 the warranty is limited to structural only. what our purchasers want, and how they After sales care expect to be treated! This is how we work… In the trade, we call it ‘snagging’. It’s the little tweaks required for any newly built home. This is another It all starts with you aspect of the Hartford Difference – to us, snagging Everything we do is geared around your needs. is an opportunity to get everything perfect, the Yes, our designs, room planning and internal fittings way we want it to be. We won’t ignore your phone are among the best you will find anywhere – but it calls.