Through the Lens of Grunge: Distortion of Subcultures In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R4C: a Benchmark for Evaluating RC Systems to Get the Right Answer for the Right Reason

R4C: A Benchmark for Evaluating RC Systems to Get the Right Answer for the Right Reason Naoya Inoue1;2 Pontus Stenetorp2;3 Kentaro Inui1;2 1Tohoku University 2RIKEN 3University College London fnaoya-i, [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Question What was the former band of the member of Mother Recent studies have revealed that reading com- Love Bone who died just before the release of “Apple”? prehension (RC) systems learn to exploit an- Articles notation artifacts and other biases in current Title: Return to Olympus [1] Return to Olympus is the datasets. This prevents the community from only album by the alternative rock band Malfunkshun. reliably measuring the progress of RC systems. [2] It was released after the band had broken up and 4 after lead singer Andrew Wood (later of Mother Love To address this issue, we introduce R C, a Input Bone) had died... [3] Stone Gossard had compiled… new task for evaluating RC systems’ internal Title: Mother Love Bone [4] Mother Love Bone was 4 reasoning. R C requires giving not only an- an American rock band that… [5] The band was active swers but also derivations: explanations that from… [6] Frontman Andrew Wood’s personality and justify predicted answers. We present a reli- compositions helped to catapult the group to... [7] Wood died only days before the scheduled release able, crowdsourced framework for scalably an- of the band’s debut album, “Apple”, thus ending the… notating RC datasets with derivations. We cre- ate and publicly release the R4C dataset, the Explanation Answer first, quality-assured dataset consisting of 4.6k Supporting facts (SFs): Malfunkshun questions, each of which is annotated with 3 [1], [2], [4], [6], [7] reference derivations (i.e. -

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

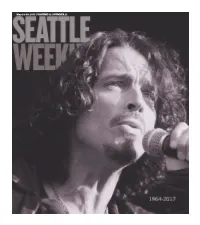

VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 Hen Chris Cornell Entered He Shrugged

May 24-30, 2017 | VOLUME 42 | NUMBER 21 hen Chris Cornell entered He shrugged. He spoke in short bursts of at a room, the air seemed to syllables. Soundgarden was split at the time, hum with his presence. All and he showed no interest in getting the eyes darted to him, then band back together. He showed little interest danced over his mop of in many of my questions. Until I noted he curls and lanky frame. He appeared to carry had a pattern of daring creative expression himself carelessly, but there was calculation outside of Soundgarden: Audioslave’s softer in his approach—the high, loose black side; bluesy solo eorts; the guitar-eschew- boots, tight jeans, and impeccable facial hair ing Scream with beatmaker Timbaland. his standard uniform. He was a rock star. At this, Cornell’s eyes sharpened. He He knew it. He knew you knew it. And that sprung forward and became fully engaged. didn’t make him any less likable. When he He got up and brought me an unsolicited left the stage—and, in my case, his Four bottled water, then paced a bit, talking all Seasons suite following a 2009 interview— the while. About needing to stay unpre- that hum leisurely faded, like dazzling dictable. About always trying new things. sunspots in the eyes. He told me that he wrote many songs “in at presence helped Cornell reach the character,” outside of himself. He said, “I’m pinnacle of popular music as front man for not trying to nd my musical identity, be- Soundgarden. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home

WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER A) Identification Historic Name: Cobain, Donald & Wendy, House Common Name: Kurt Cobain's Childhood Home Address: 1210 E. First Street City: Aberdeen County: Grays Harbor B) Site Access (describe site access, restrictions, etc.) The nominated home is located mid block near the NW corner of E 1st Street and Chicago Avenue in Aberdeen. The home faces southeast one block from the Wishkah River adjacent to an alleyway. C) Property owner(s), Address and Zip Name: Side One LLC. Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City: Ocean Shores State: WA Zip: 98569 D) Legal boundary description and boundary justification Tax No./Parcel: 015000701700 - 11 - Residential - Single Family Boundary Justification: FRANCES LOT 17 BLK 7 / MAP 1709-04 FORM PREPARED BY Name: Lee & Danielle Bacon Address: 144 Sand Dune Ave SW City / State / Zip: Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Phone: 425.283.2533 Email: [email protected] Nomination June 2021 Date: 1 WASHINGTON STATE Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation WWASHINGTON HHERITAGE RREGISTER E) Category of Property (Choose One) building structure (irrigation system, bridge, etc.) district object (statue, grave marker, vessel, etc.) cemetery/burial site historic site (site of an important event) archaeological site traditional cultural property (spiritual or creation site, etc.) cultural landscape (habitation, agricultural, industrial, recreational, etc.) F) Area of Significance – Check as many as apply The property belongs to the early settlement, commercial development, or original native occupation of a community or region. The property is directly connected to a movement, organization, institution, religion, or club which served as a focal point for a community or group. -

A Case Study of Kurt Donald Cobain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) A CASE STUDY OF KURT DONALD COBAIN By Candice Belinda Pieterse Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University December 2009 Supervisor: Prof. J.G. Howcroft Co-Supervisor: Dr. L. Stroud i DECLARATION BY THE STUDENT I, Candice Belinda Pieterse, Student Number 204009308, for the qualification Magister Artium in Counselling Psychology, hereby declares that: In accordance with the Rule G4.6.3, the above-mentioned treatise is my own work and has not previously been submitted for assessment to another University or for another qualification. Signature: …………………………………. Date: …………………………………. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several individuals that I would like to acknowledge and thank for all their support, encouragement and guidance whilst completing the study: Professor Howcroft and Doctor Stroud, as supervisors of the study, for all their help, guidance and support. As I was in Bloemfontein, they were still available to meet all my needs and concerns, and contribute to the quality of the study. My parents and Michelle Wilmot for all their support, encouragement and financial help, allowing me to further my academic career and allowing me to meet all my needs regarding the completion of the study. The participants and friends who were willing to take time out of their schedules and contribute to the nature of this study. Konesh Pillay, my friend and colleague, for her continuous support and liaison regarding the completion of this study. -

Emo Teens and the Rising Suicide Rate in SA

Emo teens and the rising suicide rate in SA An alarming number of South African teens not only harm themselves, they are actively contemplating suicide. One group that's especially at risk is the subgroup known as Emos. "I could have stopped it… she was my best friend. I never thought it was this bad. You know… we all have problems. I thought it was just another bad day." These are the words of a young grade-10 learner who recently lost her best friend due to suicide. Suicide is the cause for almost one in 10 teenage deaths in South Africa and there is growing evidence that social media sites are in part to blame for this ever increasing figure. One group of teen 'outsiders', known as Emos, and who primarily use the Internet to connect with like-minded others, seems to be particularly at risk of suicide and suicidal behaviour such as self -harming. According to a 2012 Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University (NMMU) study that analysed the content of “Emo” teenage groups on Facebook they found there is indeed a connection between teen use of social media and the 'glamourisation' of suicidal behavior. Who are these emo kids? The Emo phenomenon (emo is an abbreviation for emotional) began in the U.S. in the 1980s and spread across the world, from the US to Europe, Russia, the Middle East and South Africa. It is a largely teenage trend and the members are characterised by depression and self harming - self-harm includes attempted suicide and what's known as self harming or non-suicidal self- injury (NSSI), along with the glamourisation of suicide. -

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY Interview for Not Making It Clear That He Wasn't the Father of the Baby She Miscarried Last May

Love's Story The combative singer-actress embarks on a legal skirmish with her record label that may change what it means to be a rock star. Oh, and she also has some choice words about her late husband's bandmates, her newfound ancestry, Russell Crowe, Angelina Jolie... By Holly Millea | Mar 25, 2002 Image credit: Courtney Love Photographs by Jean Baptiste Mondino COURTNEY LOVE IS IN A LIMOUSINE TAKING HER FROM Los Angeles to Desert Hot Springs on a detox mission. "I've been on a bit of a bender after 9/11," she admits. "I've got a lot of s--- in me. I weigh 147 pounds." Which is why she's checking into the We Care colonic spa for five days of fasting. Slumped low in the seat, the 37-year-old actress and lead singer of Hole is wearing baggy faded jeans, a brown pilled sweater, and Birkenstock sandals, her pink toenails twinkling with rhinestones. On her head is a wool knit hat - 1 - that looks like something she found on the street. Last night she sat for three hours while her auburn hair extensions were unglued and cut out. "See?" Love says, pulling the cap off. "I look like a Dr. Seuss character on chemo." She does. Her hair is short and tufty and sticking out in all directions. It's a disaster. Love smiles a sad, self-conscious smile and covers up again. Lighting a cigarette, she asks, "Why are we doing this story? I don't have a record or a movie to promote. -

A Denial the Death of Kurt Cobain the Seattle Police Department

A Denial The Death of Kurt Cobain The Seattle Police Department Substandard Investigation & The Repercussions to Justice by Bree Donovan A Capstone Submitted to The Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University, New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Liberal Studies Under the direction of Dr. Joseph C. Schiavo and approved by _________________________________ Capstone Director _________________________________ Program Director Camden, New Jersey, December 2014 i Abstract Kurt Cobain (1967-1994) musician, artist songwriter, and founder of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame band, Nirvana, was dubbed, “the voice of a generation”; a moniker he wore like his faded cardigan sweater, but with more than some distain. Cobain‟s journey to the top of the Billboard charts was much more Dickensian than many of the generations of fans may realize. During his all too short life, Cobain struggled with physical illness, poverty, undiagnosed depression, a broken family, and the crippling isolation and loneliness brought on by drug addiction. Cobain may have shunned the idea of fame and fortune but like many struggling young musicians (who would become his peers) coming up in the blue collar, working class suburbs of Aberdeen and Tacoma Washington State, being on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine wasn‟t a nightmare image. Cobain, with his unkempt blond hair, polarizing blue eyes, and fragile appearance is a modern-punk-rock Jesus; a model example of the modern-day hero. The musician- a reluctant hero at best, but one who took a dark, frightening journey into another realm, to emerge stronger, clearer headed and changing the trajectory of his life. -

UNIVERSITY of ARTS in BELGRADE Center for Interdisciplinary Studies

UNIVERSITY OF ARTS IN BELGRADE Center for Interdisciplinary studies UNESCO Chair in Cultural Policy and Management Master thesis: Project on the Museum of Fashion Establishment - Following the Clothing as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Balkans since the 18th Century Projekat osnivanja Muzeja mode, koji prati modu odevanja kao kulturološki fenomen na području Balkana od 18. veka by: Selma Kronja Supervisor: Irina Subotić, PhD Belgrade, September 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Abstract 3 2. Introduction 5 3. Historical roots of the fashion development in the Balkans since the 18 th century 8 3.1. Political and geographical situation in the Balkans since the 18 th century 8 3.2. Social and cultural events that influence the global and local trends in fashion 16 3.3. Historical developments and fashion history of the population since the 18 th century till today in the Balkans 33 4. Role of the Museum of Fashion in society 49 4.1. Didactic relevance of the Museum 51 4.2. Educational and scientific role of the Museum 53 4.3. Modern concept of the Museum 56 4.4. Museum of Fashion and the media 60 5. Importance of establishing the institution for studying the fashion in the region of Balkans 66 5.1. Museum of Fashion as a unique institution in the region of Balkans 66 6. Conclusion 72 7. Bibliography 75 8. Curriculum Vitae of the author 79 1 Iris, painted by Milena Pavlović Barilli, 1928 2 ABSTRACT The main idea of the Museum of Fashion is expressing the diversity in feminine clothing since the 18 th century till today, but also the fashion of man and children, and accessories. -

Harmonic Resources in 1980S Hard Rock and Heavy Metal Music

HARMONIC RESOURCES IN 1980S HARD ROCK AND HEAVY METAL MUSIC A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Theory by Erin M. Vaughn December, 2015 Thesis written by Erin M. Vaughn B.M., The University of Akron, 2003 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by ____________________________________________ Richard O. Devore, Thesis Advisor ____________________________________________ Ralph Lorenz, Director, School of Music _____________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts ii Table of Contents LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................... v CHAPTER I........................................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 1 GOALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................................ 3 REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE............................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER II..................................................................................................................................... 36 ANALYSIS OF “MASTER OF PUPPETS” ......................................................................................