Women and Panchayat Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maharashtra Election Dates 2020 Schedule Pdf

Maharashtra election dates 2020 schedule pdf Continue Elections to the Maharashtra State Legislature 2019 ← October 21, 2019, 2024 → All 288 seats in the Maharashtra State Legislative Assembly 145 seats needed for a majority #Surveyscbrjjoc. L and Opinion Polls: Turnout61.44% (1.94%) Minority Party Minority Party Third Party Leader Devendra Fadnavis Uddhav Thackeray Ajit Pawar Party BJP SHS NCP Leader seat Nagpur southwest Baramati Last election 122 27.81% 63 19.35% 41 17.2% Seat won 1 105 56 54 Place Changes 17 7 13 Percent 25.75% 16.41% 16.7% Alliance before NDA NDA UPA Alliance After NDA MVA MVA Fourth Party Leader of the Sixth Party Balasaheb Torat Raj Thackeray Wa Rice Patan Party INC MNS AIMIM Leader seat Sangamner Byculla (lost) Last election 42 18.0% 1 2 Seats won 44 1 2 Seat changes 2 Percent 15.9% 2.3% 1.34% Alliance before UPA Alliance after MVA Map Showing the results of the elections to the Legislative Assembly of the State of Maharashtra 2019 Chief Minister before the election of Devendra Fadnavis BJP Elected Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis BJP Uddhav Thackeray Shiv SenaMaha Vikas Agadi Seat share Maharashtra Legislative Assembly elections 2019 BJP (105) , SS (56), NCP (54), INC (44), BVA (3), AIMIM (2), PJP (2), SP (2), KSP (1), PWP (1), SSS (1), RSP (1), JSS (1), CPI (M) (1), MNS (1), Ind. (13) Elections to the Maharashtra State Legislature in 2019 were held on October 21, 2019, to elect all 288 members of the State Legislature. After a 61.4% turnout, the ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Shiv Sena (SHS) won the majority of the vote. -

Haryana Assembly Election 2014

International Journal of Applied Research 2015; 1(13): 480-487 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Haryana assembly election 2014: Saffron tsunami IJAR 2015; 1(13): 480-487 www.allresearchjournal.com sweeps the state Received: 01-10-2015 Accepted: 02-11-2015 Pratap Singh, Ashok Kumar Pratap Singh Research Scholar, Dept. of Abstract Geography, M.D. University, Rohtak, Haryana, In a historic shift in power in Haryana, the Bharatiya Janata Party, for the first time has emerged as the India. largest single party with absolute majority, paving the way for the formation of a stable and “Centre- supported” government. The BJP, which only had four MLAs in 2009 assembly election in Haryana, Ashok Kumar easily crossed the halfway mark of 45 in the 90-member Assembly by winning 47 seats. The incumbent Assistant Professor (extension), Congress government led by Bhupinder Singh Hooda failed miserably despite ruling the state for 10 at S.K. Govt. College Kanwali, years. It could manage a distant third with only 15 seats. The Indian National Lok Dal (INLD), the main Rewari, Haryana, India. opposition political party in Haryana, managed to back only 19 seats, a significant drop from the 31 seats it had won back in 2009, establishing itself as a weak runner up for the second consecutive time. The HJC (Haryana Jan hit Congress-BL) and BSP have been reduced to fringe players in the state politics. The results indicate that the era of piggy back riding its way to power are over for the BJP. The BJP will no longer play second fiddle to the regional parties in the future. -

19Th June 1967

Haryana Vidhan Sabha Debates 19th June, 1967 Vol. I – No. 19 OFFICIAL REPORT CONTENT Monday, the 19th June, 1967 Pages Starred Question and Answers (19)1-107 Written Answers to Starred Question Laid on the Table of the House under Rule 45 (19)108- 173 Unstarred Question and Answers (19)173- 177 Haryana Vidhan Sabha Monday, the 19th June, 1967 The Vidhan Sabha met in the Hall of Haryana Vidhan Sabha, Vidhan Bhawan, Chandigarh, at 2.00 p.m. of the clock. Mr. speaker (Ch. Sri Chand ) in the chair. Starred questions and answers Supply of sugar to villages to Tehsil Bhiwani, district Hissar *297. Shri Bansi Lal: will the Chief minister be pleased to state whether it is a fact that the4 supply of sugar in the rural areas of Tehsil Bhiwani district Hissar, has since been stooped: if so ,the reasons there-for? Major Amir Singh (Minister of State for Rural Electrification: Yes. The supply of sugar to individual consume4rs in rural areas of Bhiwani Tehsil has been suspended from 1st march.1967 till and june, 1967 to meet the increased demand of sugar for marriages in that area. Jh calh yky % D;k eU=h egksn; crk,axs fd D;k ;g ckr nq#Lr gS fd fHkokuh rglhy es “kkfn;ksaaaaaaaaaaaaaa ds fy, Hkh phuh ugh feyrh\ jkT; eU=h% th gka( “kfn;ksa ds fygkt ls fjdkMZ ds eqrkfcd fglkj ftyk lc ls vkxs gSA Jh calh yky % D;k eU=h egksn; crk,axs fd bl bykdk es phuh dh jSxqyj lIykbZ do “kq# gks tk,xh\ jkT; ea=h % mEehn gS vxj “kfn;ksa dh tknkn es deh gqbZm rks tYnh gks tk,xhA Jh calh yky% D;k eU=h egksn; crk,xs dh “kfn;ksa es do de gks tk,xhA jkT; eU=h% bldk eSa D;k -

Loharu Assembly Haryana Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/HR-54-0118 ISBN : 978-93-5293-514-7 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 144 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE, 2009-PE and 2009-AE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10-15 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 16-17 Population Size | Sex Ratio -

Promotion of Unopposed Elections in Haryana Panchayats: a Visionary Approach

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 14 , Issue 6 (Sep. - Oct. 2013), PP 62-65 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.Iosrjournals.Org Promotion of Unopposed Elections in Haryana Panchayats: A Visionary Approach Dr. S. L. Kundu Assistant Professor in Political Science, M.K.J.K. College, Rohtak (Haryana)-India Abstract: The success of democracy depends upon free and fair elections. Elections serve as a means of communication between the public and government. It is a process through which leaders are selected by vote for a political office. The 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1992 marked a new era in the democratic set up of the country as it created Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) as third tier of the federal set up. It gives considerable attention to the nature of elections for the three levels of panchayati raj institutions. Direct elections are specified for seats at all levels. The act provides for one additional potential avenue of representation and accountability of local government. Unopposed elections are the reflection of mature democratic trend. Keywords: Election, Haryana Panchayati Raj, Panches, Panchayat Samit, Sarpanch, Unopposed Elections,,Zila Parishad. I. Introduction Elections constitute an indispensable political activity and indicate the general will of the common masses as well as provide legitimacy to the government. They are the important mechanism for checking the use of governmental arbitrary power. Election is a process through which the political opinion of the people is shaped. Through elections a modern state creates amongst its citizens a sense of participation in public affairs, and in making the people aware of their rights. -

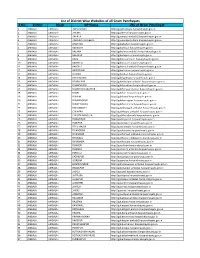

List of District Wise Websites of All Gram Panchayats S.No

List of District Wise Websites of all Gram Panchayats S.No. District Block GP Name URL of Gram Panchayat 1 AMBALA AMBALA-I ADHO MAJRA http://gpadhomajra.harpanchayats.gov.in 2 AMBALA AMBALA-I AHEMA http://gpahema.harpanchayats.gov.in 3 AMBALA AMBALA-I AMIPUR http://gpamipur-ambala1.harpanchayats.gov.in 4 AMBALA AMBALA-I ANANDPUR JALBERA http://gpanandpurjalbera.harpanchayats.gov.in 5 AMBALA AMBALA-I BABAHERI http://gpbabaheri.harpanchayats.gov.in 6 AMBALA AMBALA-I BAKNAUR http://gpbaknaur.harpanchayats.gov.in 7 AMBALA AMBALA-I BALANA http://gpbalana-ambala1.harpanchayats.gov.in 8 AMBALA AMBALA-I BALAPUR http://gpbalapur.harpanchayats.gov.in 9 AMBALA AMBALA-I BARA http://gpbara-ambala1.harpanchayats.gov.in 10 AMBALA AMBALA-I BAROULA http://gpbaroula.harpanchayats.gov.in 11 AMBALA AMBALA-I BAROULI http://gpbarouli-ambala1.harpanchayats.gov.in 12 AMBALA AMBALA-I BATROHAN http://gpbatrohan.harpanchayats.gov.in 13 AMBALA AMBALA-I BEDSAN http://gpbedsan.harpanchayats.gov.in 14 AMBALA AMBALA-I BEGO MAJRA http://gpbegomajra.harpanchayats.gov.in 15 AMBALA AMBALA-I BEHBALPUR http://gpbehbalpur-ambala1.harpanchayats.gov.in 16 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHANOKHERI http://gpbhanokheri.harpanchayats.gov.in 17 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHANPUR NAKATPUR http://gpbhanpurnakatpur.harpanchayats.gov.in 18 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHARI http://gpbhari.harpanchayats.gov.in 19 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHUNNI http://gpbhunni.harpanchayats.gov.in 20 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHURANGPUR http://gpbhurangpur.harpanchayats.gov.in 21 AMBALA AMBALA-I BHURE MAJRA http://gpbhuremajra.harpanchayats.gov.in 22 AMBALA -

Reduction of Violence Against Women: Property Ownership & Economic

Reduction of Violence Against Women: Property Ownership & Economic Independence in Rural Haryana Reduction of Violence Against Women: Property Ownership & Economic Independence in Rural Haryana By Prem Chowdhry *The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of UN Women, the United Nations or any of its affiliated organizations. Contents Introduction 4 Methodology 5 Previous Research 7 Acceptance of Violence: 11 Understanding the Cultural & Historical Context Political Economy of Haryana: 15 Changes in Gender Relationships Challenging Socio-cultural Norms 25 and Shifting Gender Relations Women’s Resistance 50 Women’s Options: Property, 55 Education and Employment References 59 Reduction of Violence against Women: Property Ownership and Employment in Rural Haryana Introduction The power structure within the household operating through specific gender hierarchies uses violence as the most potent tool of control and domination. Gender inequality derives its legitimacy and acceptance through the ideological and cultural matrix systems of rural Haryana. The wide scale prevalence of violence in rural households shows how gendered systems interact with other socio- cultural structures, not only to reinforce but to further tighten the existing gender inequalities. In this respect the influence of marital violence has been most pronounced. The present study seeks to determine the effect of property ownership and economic independence of women on the reduction of violence, especially spousal violence, in relation to rural Haryana. It seeks to analyze how and why women my acquire ownership or/and control over land/property/assets or avail of employment opportunities in a deep-rooted patriarchal cultural milieu of northern India which, in practice, is given to negate such acquisitions. -

STATE ELECTION COMMISSION HARYANA NIRVACHAN SADAN, Plot No. 2, SECTOR 17 PANCHKULA

STATE ELECTION COMMISSION HARYANA NIRVACHAN SADAN, Plot No. 2, SECTOR 17 PANCHKULA NOTIFICATION No. SEC/E-II/2010/5343 Dated: 06/07/2010 In pursuance of the provisions of sub-section (4) of Section 161 of the Haryana Panchayati Raj Act, 1994, State Election Commissioner, Haryana hereby notifies the names of the following persons who have been elected members of Zila Parishad in district Bhiwani in the General Election held in the month of June, 2010. Ward Name Father’s/Husband’s Category No. Name 1 Santra Devi Ajit Singh Scheduled Caste (Women) 2 Jagdish Diwan Singh Scheduled Caste 3 Brajpal Raj Pal Unreserved 4 Ram Chander Ram Baksh Unreserved 5 Manoj Kumar Om Parkash Unreserved 6 Parveen Kumar Prithi Singh Unreserved 7 Ramphal Ami Lal Unreserved 8 Suman Dalbir Scheduled Caste 9 Manmohan Bhurtana Chander Bhan Scheduled Caste 10 Savita Satbir Singh Scheduled Caste 11 Satywan Gopi Ram Unreserved 12 Usha Devi Sita Ram Scheduled Caste (Women) 13 Umed Singh Bairisal Singh Unreserved 14 Santosh Bhupender Women 15 Satybati Om Pal Women 16 Ramphal Jagdish Unreserved 17 Umed Singh Sube Singh Unreserved 18 Ashok Dhanpat Backward Class 19 Ravinder Kumar Diwan Singh Unreserved 20 Krishna Dharmender Women 21 Renu Bala Sumit Women 22 Monika Vijay Women 23 Rajesh Dariya Ram Unreserved 24 Prerna Devi Narvender Singh Women 25 Anita Surender Women 26 Rajbir Bharthu Unreserved 27 Sheela Devi Mala Ram Women 28 Umed Singh Chandgi Ram Unreserved 29 Brahm Parkash Gajan Singh Unreserved 2. This notification is subject to the final result of Civil Writ Petition No. 3403 of 2010 pending in the Punjab & Haryana High Court. -

TRS Thumps Congress in H'nagar with Huge Majority

Follow us on: @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 Established 1864 Published From ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 TRS ‘HUZUR’ 12 HYDERABAD DELHI LUCKNOW THURST ON RURAL INDIA RANKS 63RD ON WORLD WHAT WENT WRONG FOR BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH INDIA MUST CONG IN HUZURNAGAR? BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN BANK'S EASE OF DOING BIZ LIST VIJAYAWADA ` *LATE CITY VOL. 2 ISSUE 16 HYDERABAD, FRIDAY OCTOBER 25, 2019; PAGES 12 3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable LECTURER TURNS DIRECTOR TO BRING US NANI'S HIT { Page 11 } www.dailypioneer.com HC takes IAS officials to TRS thumps Congress in BJP-Sena to keep Maharashtra, task on Haryana heads for hung House dengue cases n H’nagar with huge majority PNS MUMBAI HYDERABAD: Aghast at the state government's failure in PNS n HYDERABAD towards striking employees Maharashtra looks set to have taking steps to prevent the Padmavathi Reddy, wife of state Congress chief had no impact on the outcome. a BJP-led government for outbreak of dengue fever, the The ruling Telangana Rashtra The constituency, with over another five years, even as the Telangana High Court on Samithi (TRS) on Thursday Uttam Kumar Reddy, could only secure 30.46 per 2.36 lakh voters, had recorded results of the Assembly polls Thursday asked the govern- wrested the Huzurnagar cent of the polled votes. Candidates of both the 84.75 per cent polling in the indicated a dip in the party's BJP+SS ment to constitute a high-level Assembly seat from the by-election held on October tally, while the Shiv Sena and CONG+NCP monitoring committee and Congress with a huge majori- Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Telugu 21. -

Rhr D ^Rcejcvu Z Wzurjvv Tcrdy

: % ! ; ! ; ; ,'"/,.=>?@ #()(#) * "#$% &' +#, &- $<&6 27 %687"7O .29.<5 %=6 "<6'=7 ! " # ""#$!#% %#%#% .%"& =&5<62 2 9"7 <6=67 27=6*>* 8 #&#%%# *0*?,,# ?? @" " =ABC=DE =?B ! # . %& '( % 627"8"6 rammed the explosive-laden SUV into a convoy of CRPF n atrocious suicide attack buses at Lethpora, 17 kilome- Akilled 43 Central Reserve ters from Srinagar at around Police Force (CRPF) personnel 3.15 pm. The major impact of $$ in highway village of Lethpora the blast was on a bus packed in south Kashmir on Thursday with off-duty troopers while the bang of the blast that it shat- as a suicide bomber rammed four other buses in tow were tered windowpanes of the explosive-laden SUV into a also badly damaged. At least, houses in a diameter of 5 km %% 79.2 The JeM was involved in Srinagar-bound convoy. This is two personnel deployed for and it was heard in many parts the Pathankot airbase terror the biggest attack on security road safety and not part of the of Srinagar city. Sources said he deadly car bomb attack strike on January 2, 2016,” the forces in three decades of insur- convoy, were also killed. that more than hundred kg of Tcarried out by the Jaish-e- official said. gency in Kashmir. Pakistan- Sources said more than a explosive has been used in the Mohammad on a convoy of the Last such attack was based Jaish-e-Muhammad out- couple of dozen personnel were attack. Central Reserve Police Force recorded on November 2, 2005 fit claimed responsibility for the wounded in the attack. -

Compiled and Edited by Kaiser Irani

T YOUTH CAMPS vl/ SATSANG YATRA (J) PEACE WORK MEDITATION CAMPS RESEARCH CENTER > SOCIAL WORKERS CAMPS COMPILED AND EDITED BY KAISER IRANI THE ELOQUENCE OF ACTION Vlmalaji's Work In India From 1978 - 1988 Compiled and Edited by Kaiser Irani Published b y : Vlmal Prakashan Tm sl 5. Theosophlcal Housing Soclely Navrangpura. Ahmedabad-380 009 Gujaral, India (c)1989 Translallon and all rights reserved : Vlmal Prakashan Trust Ahmedabad-380 009. India. Printed By: Suramya Press HinglaJ Mata Compound B/H Navrangpura Police Station. Ahmedabad-380009. Phone:446199 Rs 4 0 = 0 0. CONTENTS Page Forward Chapters I. Pilgrimage for Freedom and I - 23 Democracy II. Camps 24. 89 III. A Leap Into Ihe Flames of Violence 9 0 - 126 IV. Experiments In Restructuring 127- 152 Rural Economy V. With Ihe Assam Movement 153 - 168 VI. The Cause of Punjab and Punjablyall69 - 239 VII. Border Problem of Gujaral 241-244 VIII. Gujarat Blradarl 245 - 254 Pilgrimage For Freedom And Democracy Contents PART ONE 1. Message from Shri Ravi Shnnkcr MaharaJ 2. Pilgrimage for freedom and democracy ' 3. Letter to friends Joining ihe Pilgrimage 4. Our Pilgrimage 5. Preamble 6. Lok Satsang Yalra: Talks by Vimalaji during Yalra in Gujarat and Rajasthan 7. Discussion with Sarvodaya workers In Bikaner, Rajasthan 8. Newsletter of the second phase of Lok Satsang Yalra 9. Report from Punjab PART TWO Resume Of The Pilgrimage 1. Gujarat 2. Rajasthan 3. Madhya Pradesh 4. Punjab 5. Himachal Pradesh 6. Haryana BLESSINGS FROM^SRI RAVI SHANKAR MAHARAJ I am v ery g la d to Iearn about the prqfect undertaken by V lm a la ben and her Satsangi friends to contact the people and waken them. -

Pok Is Controlled by Terrorists

Thousands of candles can be lighted from a single candle, and SATURDAY the life of the candle will not be OCTOBER 26, 2019 shortened. Happiness never CHANDIGARH decreases by being shared. VOL. XXIII, NO. 257 PAGES 12 Buddha Rs. 2 YUGMARGYOUR REGION, YOUR PAPER SBI Q2 profit jumps by Last date for AISSEE 2020 Haryana team beats Gujarat 219 pc at Rs 3,012 cr extended till 31st to win gold medal ...PAGE 11 ...PAGE 3 .... PAGE 3 PoK is controlled by BJP-JJP to form govt in Hry terrorists: Army Chief AGENCY Dushyant Chautala to be Deputy CM NEW DELHI, OCT 25 Army Chief General Bipin Rawat on RAJENDRA KHATRY Friday said that Pakistan Occupied Pak intruder killed CHANDIGARH, OCT 25 Kashmir was not controlled by its Pak- istani establishment but by terrorists. on Pb border Leader of JJP, Dushyant Chauta- "The territory which has been ille- JALANDHAR: A Pakistani in- la has announced to form a coali- gally occupied by Pakistan is not con- truder was killed by Border Secu- tion government with BJP in trolled by the Pakistani establishment, rity Force (BSF) near Bharopal in Haryana. In a joint press confer- it is controlled by terrorists. PoK is ac- Amritsar sector. ence, Chief Minister Manohar tually a terrorist-controlled country or The BSF, in a press communique Lal Khattar and JJP chief a terrorist-controlled part of Pakistan," here, on Friday said the BSF Dushyant Chautala have jointly General Rawat said delivering the KM Infantry soldiers will troops deployed at the BoP expressed happiness to join hand Cariappa Memorial lecture here Bharopal observed suspicious movement of an intruder on with each others.