Environmental Assessment for the Dosewallips Engineered Log Jam Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Brothers Wilderness Air Quality Report, 2012

The Brothers Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 241 Wilderness Name: The Brothers Wilderness The Brothers Wilderness Air Quality Report National Forest: Olympic National Forest State: WA Counties: Jefferson General Location: Olympic Peninsula Acres: 16,337 Thursday, May 17, 2012 Page 1 of 4 The Brothers Wilderness Air Quality Report Wilderness ID: 241 Wilderness Name: The Brothers Wilderness Wilderness Categories Information Specific to this Wilderness Year Established 1984 Establishment Notes 99-635, Washington State Wilderness Act of 1984 Designation Clean Air Act Class 2 Administrative Olympic National Forest Unique Landscape Features The Brothers Wilderness is located on the eastern flanks of the Olympic National Forest just South of Buckhorn Wilderness and north of Mt. Skokomish Wilderness. Between moss- and fern-laden banks, the Dosewallips and Hamma Hamma Rivers run cold and clear north and south, respectively, of the borders of The Brothers Wilderness. At 6,866 feet, The Brothers is the highest peak in the area, with a distinct double summit that ranks among the most popular climbs in the Olympics. Through the center of the Wilderness the Duckabush River splashes down a wide and lovely glacier-carved valley shadowed by tall hemlock, fir, and cedar. From the Duckabush the terrain rises steeply into a mazelike network of forested ridges that peak on The Brothers to the south and 5,701-foot Mount Jupiter to the north. In the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains, the area collects about 80 inches of precipitation each year, and temperatures stay temperate, rarely rising above 80 degrees Fahrenheit and seldom freezing along the river. -

Geologic Map of the Brinnon 7.5-Minute Quadrangle, Jefferson and Kitsap Counties, Washington

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE BRINNON 7.5-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, JEFFERSON AND KITSAP COUNTIES, WASHINGTON by Michael Polenz, Eleanor Spangler, Logan A. Fusso, David A. Reioux, Ryan A. Cole, Timothy J. Walsh, Recep Cakir, Kenneth P. Clark, Jeffrey H. Tepper, Robert J. Carson, Domenico Pileggi, and Shannon A. Mahan WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Map Series 2012-02 December 2012 DISCLAIMER Neither the State of Washington, nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the State of Washington or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the State of Washington or any agency thereof. INDEMNIFICATION Research supported by the U.S. Geological Survey, National Cooperative Geologic Mapping Program, under USGS award number G11AC20236. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government. WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES -

June 2010 Penwicle

JUNE Ed Book Photography Monday, June 14, 7 pm 2010 Presented by: Ed Book Ed Book is a PWC member and past presenter, and was the PWC Artisan featured at the April PWC meeting. Ed will be sharing his photos of snow geese at the Skagit River delta in spring and the autumn oaks of Klickitat County (the best autumn color of Washington), just north of the Columbia River Gorge. The Skagit River delta serves as a wintering ground for hundreds of thousands of snow geese, trumpeter swans, and bald eagles. It's located at the north end of Puget Sound at the mouth of the Skagit River, which collects water from the northern Cascade Mountain Range and carries it to Puget Sound. Top: Snow geese wintering at Fir Island in the Skagit River delta fly in formation close to each other to reduce air resistance. Bottom: Snow geese wintering at Fir Island fly in the early morning with Whitehorse Mountain in the background. Photos courtesy of Ed Book, © edbookphoto.com Perry Avenue in East Bremerton. The public is cordially invited. is cordially The public Avenue Perry in East Bremerton. tsap Unitarian Universalist Fellowship on Fellowship Universalist Unitarian tsap Monday of every month at 7 pm at at every the month Ki Monday of Peninsula Club meets second Peninsula Wilderness on the Monthly MAP: Monthly Activity Planning Meeting & June Potluck Board Meeting Friday, June 25, 6:30 pm Thursday, June 10, 6 pm Board Meeting, 7 pm MAP Contact: Paul Dutky, 360-479-2683, [email protected] Contact: John & Ellen Knott, 360-710-1158 Visit with fellow PWCers at Paul’s home in Bremerton. -

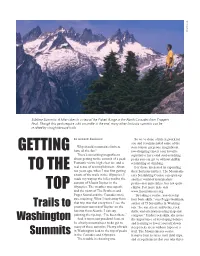

Feature 08-04

HOLAND S ON Night R Hiking Sublime Summits: A hiker takes in a view of the Pickett Range in the North Cascades from Trappers Peak. Though this peak require a bit scramble at the end, many other fantastic summits can be reached by straightforward trails. By Andrew Engelson So we’ve done a little legwork for you and recommended some of the Why should mountain climbers state’s most gorgeous, magnificent, GETTING have all the fun? jaw-dropping (insert your favorite There’s something magnificent superlative here) and soul-satisfying about getting to the summit of a peak. peaks you can get to without skill in Fantastic views, high clear air, and a scrambling or climbing. real sense of accomplishment. About For those interested in expanding TO THE ten years ago, when I was first getting their horizons further, The Mountain- a taste of the trails in the Olympics, I eers Scrambling Course can open up made my way up the killer trail to the another world of intermediate summit of Mount Jupiter in the peaks—not quite hikes, but not quite TOP Olympics. The weather was superb, climbs. For more info, visit and the views of The Brothers and www.mountaineers.org. Puget Sound and the Cascades were “By taking a course, you develop awe-inspiring. What I took away from four basic skills,” says Peggy Goldman, that trip was that every time I see the author of 75 Scrambles in Washing- Trails to prominent summit of Jupiter on the ton. “Ice axe arrest, self-belay, rock horizon from Seattle, I can say, skills, and orientation using map and pointing the tip-top, “I’ve been there.” compass.” Under rock skills, she notes Washington And, it turns out you don’t have to the importance of developing balance be a burly mountaineer to do get to and learning to lower yourself down many of these summits. -

Mountain Goats in the Greater Yellowstone Area: Challenges for Management, Wildlife Society Bulletin, July 10, 2016

EXHIBIT INDEX BATES # DOCUMENT Ex001 - Robin J. Innes, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain 056 Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Oreamnos americanus, Fire Effects Information System (2011), Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ (last visited August 8, 2017) Ex057 - Elizabeth Flesh et al., Range Expansion and Population Growth of Nonnative 066 Mountain Goats in the Greater Yellowstone Area: Challenges for Management, Wildlife Society Bulletin, July 10, 2016 Ex067 - Rolf Johnson, Washington Dept. of Game, Mountain Goats and Mountain Sheep 081 of Washington, January 1983 (excerpt) Ex082 - Clifford Rice & Don Gay, Effects of Mountain Goat Harvest on Historic and 100 Contemporary Populations, 91 Northwestern Naturalist 40 (2010) Ex101 - Bureau of Land Management, Status of the Science on Questions that Relate to 112 BLM Plan Amendment Decisions and Peninsular Ranges Bighorn Sheep (2001) Ex113 - Craig A. Stockwell & Gary C. Bateman, Conflicts in National Parks: A Case 124 Study of Helicopters and Bighorn Sheep Time Budgets at the Grand Canyon, 56 Biological Conservation 317 (1991) Ex125 - Steeve D. Cote, Mountain Goat Responses to Helicopter Disturbance, 24(4) 130 Wildlife Society Bulletin 681 (1996) Ex131 - Alexandre L. Rasiulis et al., The Effect of Radio-Collar Weight on Survival of 135 Migratory Caribou, 78(5) The Journal of Wildlife Management 953 (2014) Ex136 - Steven J. Cooke et al., Troubling issues at the frontier of animal tracking for 138 conservation and management, 00 Conservation Biology 0, 1 (2017) Ex139 - National Park Service, Olympic Nat’l Park, Draft Mountain Goat Management 166 Plan / Environmental Impact Statement (2017) (excerpt) Ex167 - National Park Service, Olympic Nat’l Park, Olympic National Park Minimum 192 Requirements Analysis, 2017 Ex193 - U.S. -

July 2010 Penwicle

JULY PWC Annual Picnic Monday, July 12, 6:30 pm 2010 Location: Raab Park, Poulsbo The Annual PWC Picnic takes the place of the July General Meeting and will be held at Raab Park in Poulsbo. Burgers, salmon burgers, veggie burgers, hot dogs, buns, condiments, potato salad, macaroni salad, desserts, and place settings will be provided. If you would like to bring something (i.e., chips, munchies, fruit,…) to share, feel free to do so. Water coolers will be provided, and cups will be available, but members are encouraged to bring their own reusable cups or bottles to minimize the amount of garbage generated. Bring your own beverage (alcohol is permitted). Activities include a Tall Tales Contest and Tug-O-War, and you are encouraged to bring your own yard games (Frisbee, croquet, bocce ball, etc.) to share. Perry Avenue in East Bremerton. The public is cordially invited. is cordially The public Avenue Perry in East Bremerton. tsap Unitarian Universalist Fellowship on Fellowship Universalist Unitarian tsap Monday of every month at 7 pm at at every the month Ki Monday of Peninsula Club meets second Peninsula Wilderness on the Photos from a recent trip to Lena Lake and Valley of the Silent Men, courtesy of Steve Osburn. Monthly Date Outing / Meeting Contact 7/3-5 Climb The Brothers David Cossa, 360-871-5577 7/4 Sea Kayak Hood Canal Charlie Michel, 360-830-4984 7/6-8 Backpack Royal Basin Doug Terry, 360-550-7911, [email protected] 7/8 MAP Meeting Steve & Nancy Osburn, 360-697-5982 7/9-11 Sea Kayak Lummi and Clark Islands Paul Dutky, 360-479-2683, -

WRIA 16 Final Report.Doc

Hydrogeologic Study of the Lower Dosewallips/Brinnon Area Prepared for: WRIA 16 Planning Unit Funding Source: WRIA 16 Base Grant, Department of Ecology Grant #G9900020 As pectconsulti ng IN-DEPTH PERSPECTIVE 179 Madrone Lane North 811 First Avenue #480 Bainbridge Island, WA 98110 SeaUle, WA 98104 (206) 780-9370 (206)-328-7443 Project No. 0301 16-001-05 - March 30, 2005 HYDROGEOLOGIC STUDY OF THE LOWER DOSEWALLIPS/BRINNON AREA Prepared for: WRIA 16 Planning Unit Funding Source: WRIA 16 Base Grant, Department of Ecology Grant #G9900020 Project No. 030116-001-05 • March 30, 2005 Aspect Consulting, LLC Erick W. Miller tEXP1REs 02J011or- Erick W. Miller, LHG Joseph S. Lubischer, P.E. Senior Associate Hydrogeologist Project Engineer [email protected] [email protected] W:\030116 WRIA 16\FinaJ Report\WRIA 16 Final Report.doc ~79 Madrone Lane North •• ASPECT CONSULTING Contents Executive Summary........................................................................................... 1 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Background .................................................................................................. 3 1.2 Overview of Dosewallips Basin.................................................................... 3 1.3 Purpose and Scope...................................................................................... 5 2 Geologic Conditions and Basin Glaciation .............................................. 6 2.1 Previous -

Summits on the Air USA (W7W)

Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W7W) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S39.1 Issue number 2.0 Date of issue 01-Dec-2016 Participation start date 01-July-2009 Authorised Date 08-Jul-2009 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Darryl Holman, WW7D, [email protected] Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air – ARM for USA W7W-Washington Table of contents Change Control ................................................................................................................... 4 Disclaimer ........................................................................................................................... 5 Copyright Notices ............................................................................................................... 5 1.0 Association Reference Data .......................................................................................... 6 2.1 Program Derivation ....................................................................................................... 7 2.2 General Information ...................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Final Access, Activation Zone, and Operating Location Explained ............................. 8 2.4 Rights of Way and Access Issues ................................................................................ -

THE MOUNTAINEER VOLUME XIX Number One December 15, 1926

THE MOUNTAINEER VOLUME XIX Number One December 15, 1926 Olympic Peninsula PUBLISttEt> BY THE MOUNTAINJ!,ER.S INCOllPOI\ATED 5 EAT TL E WAS H I N Ci TON. COPYRIG-HT. 1.926 The Mounrtiinee-n IncorporareJ w��Ta.PtN ,afUNTING co .. .. Oii MARION. atATTl I'. The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME NINETEEN Number One December 15, 1926 Olympic Peninsula Incorporated 1913 Organized 1906 EDITORIAL BOARD, 1926 Winona Bailey Lulie Nettleton Arthur Gist Agnes E. Quigley :Mildred Granger C. F. Todd Else Hubert Mrs. Stuart P. Walsh Mrs. Joseph T. Hazard, Associate Editor: Subscription Price, $2.00 Per Year . �nnual (only) Seve11ty-fiYe Cents. Published by The Mountaineers I ncorPora ted Seattle, Washington Entered as �eeond-class matter, December 15, 1920, at the Postoffice at SeaHle, Washington, under the Act of ?.Iarch 3, 1879. WHITE GLACIER Thomas E. Jeter This glacier whose streams feed the Hoh River thousands of feet below lies on the north side of Mount Olympus. CONTENTS Page Greetings ·····----------------------------------·--------·--·······Vilhjalmur Stefansso11 1926 Summer Outing in the Olympics............ Edmond S. Meany,],·..... 7 Down the Quinault River (Poem) ................Edmond S. Meany..... .... 19 Short Hikes in the Olympics............ ................ Ronald R. Ruddi111a11. 21 Some Unexplored Sections of the Olympics.... Theodore C. Lewis........ 25 Making the Olympics Accessible. .............. ......Frank H. Lamb....... 27 A Horne in the Olympics.......................... .....Margaret McCamey 30 Kidnaping in the Olympics.............................. Doris Huelsdonk .... 34 From the Leader of the Press Expedition ........J. H. Christie.......... 37 Summer Outing of 1927 ................... ............._F. B. Farquharson. 40 In Memoriam --------··-··········------·······················Edmond S. Meany.... 41 Members of the 1926 Summer Outing .................................... 42 Mountaineer Activities (Pictures)......... ........................................ 43 Our Forest Theatre................................. -

Hiking Guide

Olympic Hiking Guide Hiking Olympic National Forest’s Unprotected Wildlands The Olympic Mountains are known internationally as one of the finest remaining natural areas on Earth. Visitors flock to the region during all seasons to experience outstanding forests, rivers, subalpine meadows, and glaciers firsthand. Most visit only the most well known attractions, leaving the more obscure (though often equally impressive) areas to those with the curiosity and willingness to seek them out. What follows are descriptions of how to access some of these special places in our Olympic National Forest, ranging from easy day hikes to energetic, multi-day adventures. What distinguishes the hikes below, however, is that each travels a wild landscape that has yet to receive ironclad protection via congressional Wilderness designation. As a result, despite their beauty and wildlife, these areas remain vulnerable to future logging, destructive road building, and off-road vehicles. Immensely valuable in their own right, the continued integrity of these areas directly contributes to the health of the Olympic Ecoregion as a whole, which has been recognized as a Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site. But don’t take our word for it—visit these areas, form your own opinion, and let our leaders in Congress know what you think. This free publication is offered by Olympic Forest Coalition, an organization dedicated to protecting our Olympic ForestPage and Aquatic Ecosystem. TRAIL INDEX Deer Ridge trail #846…………………………………………………………………………… 3 Ned Hill trail #837………………………………………………………………………………... 3 Lower Graywolf trail #834……………………………………………………………………… 3 Lower Dungeness trail #833…………………………………………………………………… 4 Upper Dungeness trail #833…………………………………………………………………… 4 Gold Creek trail #830……………………………………………………………………………. 4 Little Quilcene/Dirty Face Ridge trail #835…………………………………………………. -

Brinnon Subarea Planning Group

BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS PREFERRED ALTERNATIVE DRAFT MAY 1, 2002 MODIFIED FROM JANUARY 16, 2002 DRAFT RECOMMENDED BY PLANNING COMMISSION AND AUGUST 28, 2001 DRAFT RECOMMENDED BY BRINNON SUBAREA PLANNING GROUP Brinnon Subarea Plan A Chapter of the Jefferson County Comprehensive Plan Brinnon Subarea Planning Group Original Membership, 1999-2000 Linda Tudor, Chair Cedric Lindsay Lynnette Antijunti Kate Marsh, Recorder Joy Baisch Mike Matthews Richard Coone Tom McNerney Dalila Dowd Eleanor Sather John Dowd Bud Schindler Charles Finnila George Sickel Jean Johnson Lea Silsbee Stan Johnston Charles Springer Final Membership Recommending August 28, 2001 Draft Linda Tudor, Chair Cedric Lindsay Joy Baisch Kate Marsh, Recorder Dalila Dowd Tom McNerney John Dowd Bud Schindler Charles Finnila George Sickel Jean Johnson Charles Springer Jefferson County Representatives Board of County Commissioners Richard Wojt, Chair, District 3 Glen Huntingford, District 2 Dan Titterness, District 1 David Goldsmith, County Administrator Department of Community Development Al Scalf, Director of Community Development Josh D. Peters, Associate Planner Warren Hart, AICP; (former) Deputy Director W. Lauren Mark, (former) Associate Planner Special Consultant Mark Personius, AICP; Planning Director Earth Tech, Inc. The work of the Special Consultant was funded in part through the Community Development Block Grant program. Table of Contents Page Vision Statement ...............................................................................................................................................................1 -

Student Dies in Car Crash the Race

the ThunderWord Highline Community College | May 9, 2013 | Volume 50, Issue 25 Student dies in car crash The race By Thunderword Staff is on for Highline’s Hip Hop Club student members plan to honor their late former president at a dance summit next week. elections Hip Hop Summit 2013: In Loving Memory of Asha Salim By Racquel Arceo will be held on May 17 on the Staff Reporter first floor of the Student Union from 4-11 p.m. Leadership of Highline’s Salim died last week on Student Government for the Wednesday night when the car 2013-2014 school year will in which she was riding crashed be determined over the next while heading southbound week. At stake are the offices along Interstate 5 in Seattle. of president and vice president. Salim, who was not wearing The candidates will be cam- a seatbelt, was ejected from the paigning all over campus, in vehicle and died at the scene. hopes of gaining votes. There were six other people Voting will be strictly on- in the car, including one woman line and will open on May 15 who was taken to Harborview at 8:30 a.m. and close on May Medical Center in critical con- 16 at midnight. Voting stations dition. The driver is suspected will be available in the Student of drunk driving and vehicular Friends of Salim held a vigil for her last Friday evening. Union during regular hours. homicide. The online ballot will fea- For many of Salim’s former way she would want it,” Duong smiled too.