Oceania, Regional Overviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

KNOTLESS NETTING in AMERICA and OCEANIA T HE Question Of

116 AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST [N. s., 37, 1935 48. tcdbada'b stepson, stepdaughter, son or KNOTLESS NETTING IN AMERICA daughter of wife's brother or sis AND OCEANIA By D. S. DAVIDSON ter, son or daughter of husband's brother or sister: reciprocal to the HE question of trans-Pacific influences in American cultureshas been two preceding terms 49. tcdtsa'pa..:B T seriously debated for a number of years. Those who favor a trans step~grandfather, husband of oceanic movement have pointed out many resemblances and several grandparent's'sister 50. tCLlka 'yaBB striking similarities between certain culture traits of the New World and step-grandmother, wife of grand Oceania. The theory of a historical relationship between these appearances parent's brother 51. tcde'batsal' is based upon the hypothesis that independent invention and convergence step-grandchild, grandchild of speaker's wife's (or speaker's hus in development are not reasonable explanations either for the great number band's) brother or sister: recipro of resemblances or for the certain complexities found in the two areas. c~l to the two preceding terms The well-known objections to the trans-Pacific diffusion theory can 52. tsi.J.we'bats husband Or wife of grandchild of be summarized as follows: speaker or speaker's brother or 1. That many of the so-called similarities at best are only resemblances sister; term possibly reciprocal between very simple traits which might be independently invented or 53. tctlsxa'xaBll son-in-law or daughter-in-law of discovered. speaker's wife's brother or sister, 2. -

South America Wine Cruise!

South America Wine Cruise! 17-Day Voyage Aboard Oceania Marina Santiago to Buenos Aires January 28 to February 14, 2022 Prepare to be awestruck by the magnificent wonders of South America! Sail through the stunning fjords of Patagonia and experience the cheerfully painted colonial buildings and cosmopolitan lifestyle of Uruguay and Argentina. Many people know about the fantastic Malbec, Torrontes, Tannat, and Carminiere wines that come from this area, but what they may not know is how many other great styles of wine are made by passionate winemakers throughout Latin America. This cruise will give you the chance to taste really remarkable wines from vineyards cooled by ocean breezes to those perched high in the snow-capped Andes. All made even more fun and educational by your wine host Paul Wagner! Your Exclusive Onboard Wine Experience Welcome Aboard Reception Four Exclusive Wine Paired Dinners Four Regional Wine Seminars Farewell Reception Paul Wagner Plus Enjoy: Renowned Wine Expert and Author Pre-paid Gratuities! (Expedia exclusive benefit!) "After many trips to Latin America, I want to share the wines, food and Complimentary Wine and Beer with lunch and dinner* culture of this wonderful part of the Finest cuisine at sea from Executive Chef Jacques Pépin world with you. The wines of these FREE Unlimited Internet (one per stateroom) countries are among the best in the Country club-casual ambiance world, and I look forward to Complimentary non-alcoholic beverages throughout the ship showing you how great they can be on this cruise.” *Ask how this can be upgraded to the All Inclusive Drink package onboard. -

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." the Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Africa in Oceania." The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 169–182. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 27 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-009>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 27 September 2021, 09:12 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 9 Africa in Oceania Māui and Legba Hone Taare Tikao, an Ngāi Tahu scholar involved in Te Kotahitanga, the Māori Parliament movement of the late nineteenth century, puts the pieces together: Māui must have visited Africa in one of his epic journeys.1 For once upon a time Māui had turned a thief called Irawaru into a dog, and since then some Māori have considered the dog to be their tuākana (elder sibling). In the 1830s a trading ship from South Africa arrives at Otago harbour. On board is a strange animal that the sailors call a monkey but that the local rangatira (chiefs) recognize to be, in fact, Irawaru. They make speeches of welcome to their elder brother. It is 1924 and the prophet Rātana visits the land that Māui had trodden on so long ago. He finds a Zulu chief driving a rickshaw. He brings the evidence of this debasement back to the children of Tāne/ Māui as a timely warning as to their own standing in the settler state of New Zealand. It is 1969 and Henderson Tapela, president of the African Student’s Association in Aotearoa NZ, reminds the children of Tāne/Māui about their deep-seated relationship with the children of Legba. -

European Collection 2015

European Collection 2015 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN & THE RIVIERAS EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN & GREEK ISLES NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES CONTINENTAL EUROPE CONTENTS 2 EXPERIENCE 96 TRANSOCEANIC VOYAGES The OlifeTM 104 gRAND VOYAGES 16 TASTE The Finest Cuisine at Sea 114 EXPLORE ASHORE Shore Excursion Collections & Land Tour Series 28 VALUE Best Value in Upscale Cruising 123 HOTEL PROGRAMS Pre- & Post-Cruise Hotel Programs 32 OcEANIA CLUB 126 SUITES & STATEROOMS 34 DESTINATION SPECIALISTS Culinary Discovery ToursTM & New Ports of Call 136 DECK PLANS 42 WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN 140 PROGRAMS & INFORMATION & THE RIVIERAS Travel Protection & Air Program Details 62 EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN 142 CRUISE CALENDAR & GREEK ISLES 144 EXPERIENCE OcEANIACRUISES.COM 74 NORTHERN EUROPE & BRITISH ISLES 145 GENERAL INFORMATION Oceania Club Terms & Conditions 90 CONTINENTAL EUROPE ON THE COVER Scottish kilts originate back to the 16th century and were traditionally worn as full length garments by Gaelic-speaking male Highlanders of northern Scotland POINTS OF DISTINCTION n FREE AIRFARE* on every voyage n Mid-size, elegant ships catering to just 684 or 1,250 guests n Finest cuisine at sea, served in a variety of distinctive open-seating Europe Collection restaurants, at no additional charge n Gourmet culinary program crafted 2015 by world-renowned Master Chef Jacques Pépin THE MAGIC OF THE OLD WORLD | When millenniums of history and great works n of art meet captivating cultures and generous smiles, you know you’ve arrived in Europe. Spectacular port-intensive itineraries featuring overnight visits and extended From Michelangelo’s David in Florence to Rembrandt’s masterpieces in Amsterdam, you evening port stays will be awed and inspired. Stand on the Acropolis in Athens or explore the gilded czar palaces in St. -

BREAKDOWN of SUB-REGIONS Americas

BREAKDOWN OF SUB-REGIONS Americas Atlantic Islands and Central and Canada Eastern US Latin America Southwest US Argentina Atlantic Canada Kansas City Boston Atlantic Islands British Columbia Nebraska Hartford Brazil A Canadian Prairies Oklahoma Maine Brazil B Montreal & Quebec Southwest US A New York A Central America Toronto Southwest US B New York B Chile St. Louis Philadelphia Colombia Pittsburgh Mexico Washington DC Peru Western New York Uruguay Midwest US Southeastern US Western US Chicago Florida Colorado Cleveland Greater Tennessee Desert US Indianapolis Louisville Hawaii Iowa Mid-South US Idaho Madison North Carolina Los Angeles Milwaukee Southern Classic New Mexico Minnesota Virginia Northern California Southern Ohio Orange County West Michigan Portland Salt Lake San Diego Seattle Spokane Asia Pacific Oceania Eastern Asia Southeastern Asia Southern Asia Brisbane Beijing Cambodia Bangladesh Melbourne Chengdu Indonesia India A New Zealand Hong Kong Malaysia India B Perth Japan Philippines India C Sydney Korea Singapore Nepal Mongolia Thailand Pakistan Shanghai Vietnam Sri Lanka Shenzhen A Shenzhen B Taiwan Europe, Middle East, and Africa Sub-Saharan Africa Eastern Europe Northern Europe Southern Europe Ethiopia Bulgaria Denmark & Norway Croatia Ghana Czech Republic Finland Cyprus Kenya Hungary Ireland Greece Mauritius Kazakhstan Sweden Israel Nigeria A Poland A Istanbul Nigeria B Poland B Italy Rwanda Romania Portugal South Africa Russia A Serbia Tanzania Russia B Slovenia Uganda Slovakia Spain Zimbabwe Ukraine A Ukraine B Middle East and Western Europe North Africa Austria Bahrain Benelux Doha France Egypt Germany Emirates Switzerland Jordan Kuwait Lebanon Morocco Oman Saudi Arabia . -

Oceania & Antarctica, Locate and Describe

Oceania & Antarctica, locate and describe » Activity 1. In pairs, match geographical features names in the word bank with the correct description. ___ Antarctic Peninsula ___ Ayers Rock/Uluru ___ Darling River ___ Great Barrier Reef ___ Great Dividing Range ___ Melanesia ___ Micronesia ___ New Zealand ___ Polynesia ___ Tasmania 'Meeting points': Torres Strait Note: In bold, description verbs for your cards. southern Pacific Ocean. Historically, the islands have been known as South Sea Islands even | 1 | • It is a group of islands situated some 1,500 though the Hawaiian Islands are located in the North kilometres east of Australia. In fact, it is an island Pacific. country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean and it comprises two main landmasses and around 600 | 6 | • It is an island located 240 km to the south of smaller islands. the Australian mainland, separated by the Bass Strait. The island covers 64,519 km². | 2 | • It is a large sandstone rock formation in central Australia. This rock is sacred to the Aboriginal | 7 | • It is Australia's most substantial mountain people of the area. It lies 335 km south west of the range. It stretches more than 3,500 kmfrom the nearest large town, Alice Springs. The area around northeastern tip of Queensland, running the entire the formation is home to ancient paintings. length of the eastern coastline. | 3 | • It is a subregion of Oceania extending from | 8 | • It is the third longest river in Australia, New Guinea island in the southwestern Pacific measuring 1,472 km from its source in northern Ocean to the Torres Strait, and eastward to Fiji. -

THE LIMITS of SELF-DETERMINATION in OCEANIA Author(S): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol

THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Author(s): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1/2, The Caribbean and Pacific in a New World Order (March/June 2007), pp. 182-208 Published by: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27866500 . Accessed: 11/10/2013 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of the West Indies and Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social and Economic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 133.30.14.128 on Fri, 11 Oct 2013 20:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Social and Economic Studies 56:1&2 (2007): 182-208 ISSN:0037-7651 THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Terence Wesley-Smith* ABSTRACT This article surveys processes of decolonization and political development inOceania in recent decades and examines why the optimism of the early a years of self government has given way to persistent discourse of crisis, state failure and collapse in some parts of the region. -

Global and Continental Drought in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century: Severity–Area–Duration Analysis and Temporal Variability of Large-Scale Events

1962 JOURNAL OF CLIMATE VOLUME 22 Global and Continental Drought in the Second Half of the Twentieth Century: Severity–Area–Duration Analysis and Temporal Variability of Large-Scale Events J. SHEFFIELD Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey K. M. ANDREADIS Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington E. F. WOOD Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey D. P. LETTENMAIER Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington (Manuscript received 10 July 2008, in final form 15 October 2008) ABSTRACT Using observation-driven simulations of global terrestrial hydrology and a cluster algorithm that searches for spatially connected regions of soil moisture, the authors identified 296 large-scale drought events (greater than 500 000 km2 and longer than 3 months) globally for 1950–2000. The drought events were subjected to a severity–area–duration (SAD) analysis to identify and characterize the most severe events for each continent and globally at various durations and spatial extents. An analysis of the variation of large-scale drought with SSTs revealed connections at interannual and possibly decadal time scales. Three metrics of large-scale drought (global average soil moisture, contiguous area in drought, and number of drought events shorter than 2 years) are shown to covary with ENSO SST anomalies. At longer time scales, the number of 12-month and longer duration droughts follows the smoothed variation in northern Pacific and Atlantic SSTs. Globally, the mid-1950s showed the highest drought activity and the mid-1970s to mid-1980s the lowest activity. -

3. EAST and SOUTH-EAST ASIA, OCEANIA and the PACIFIC Regional Overview

3. EAST AND SOUTH-EAST ASIA, OCEANIA AND THE PACIFIC Regional Overview Methamphetamine continues to dominate the ATS market dismantled laboratories in the region intended solely for in East and South-East Asia, Oceania and the Pacific. ATS methamphetamine manufacture dropped from about 410 seizures in the region have annually increased from about in 2008 to less than 180 in 2009, these have remained at 13 tons in 2008 to just under 40 tons in 2012. The rapid about 150 in 2010 and 2011. The annual number of dis- rise of ATS seizures over the years is primarily attributable mantled “ecstasy” laboratories have remained at around 30 to the increase of methamphetamine seizures which about between 2008 and 2010, but have increased to just under tripled from less than 12 tons in 2008 to 36 tons in 2012. 140 in 2011. Having increased from about 0.1 tons in 2008 to 2.3 tons in 2011, amphetamine seizures in the region have dropped Fig. 12: Dismantled ATS laboratories reported in again to less than 0.2 tons in 2012. Seizures of "ecstasy" East and South-East Asia, Oceania and the have also fluctuated over the years, but have more than Pacific, 2008-2011 tripled in 2012 to 1.9 tons. However, both amphetamine 900 and “ecstasy” seizures in the region have remained at rela- 800 tively low levels, whilst methamphetamine seizures have 700 annually made up more than 90 per cent of total ATS sei- zures for a number of years. 600 500 Fig. 11: Total ATS seizures reported in East and 400 South-East Asia, Oceania and the Pacific, 2008-2012 300 45,000 Number Laboratories of 200 40,000 100 35,000 0 30,000 2008 2009 2010 2011 25,000 20,000 "Ecstasy" Methamphetamine/Amphetamine 15,000 Methamphetamine 10,000 Quantity seized (kg) seized Quantity 5,000 Source: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Annual Report Questionnaire 2008-2011. -

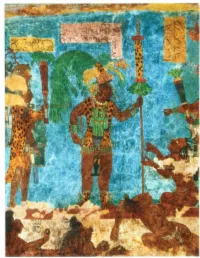

CHAPTER 4 EARLY SOCIETIES in the AMERICAS and OCEANIA 69 G 11/ F of M C \I C O ' C Hi Ch~N B A

n early September of the year 683 C. E., a Maya man named Chan Bahlum grasped a sharp obsidian knife and cut three deep slits into the skin of his penis. He insert ed into each slit a strip of paper made from beaten tree bark so as to encourage a continuing flow of blood. His younger brother Kan Xu I performed a similar rite, and other members of his family also drew blood from their own bodies. The bloodletting observances of September 683 c.E. were political and religious rituals, acts of deep piety performed as Chan Bahlum presided over funeral services for his recently deceased father, Pacal, king of the Maya city of Palenque in the Yu catan peninsula. The Maya believed that the shedding of royal blood was essential to the world's survival. Thus, as Chan Bahlum prepared to succeed his father as king of Palenque, he let his blood flow copiously. Throughout Mesoamerica, Maya and other peoples performed similar rituals for a millennium and more. Maya rulers and their family members regularly spilled their own blood. Men commonly drew blood from the penis, like Chan Bahlum, and women often drew from the tongue. Both sexes occasionally drew blood also from the earlobes, lips, or cheeks, and they sometimes increased the flow by pulling long, thick cords through their wounds. According to Maya priests, the gods had shed their own blood to water the earth and nourish crops of maize, and they expected human beings to honor them by imitating their sacrifice. By spilling human blood the Maya hoped to please the gods and ensure that life-giving waters would bring bountiful harvests to their fields. -

Australia and Oceania: Physical Geography

R E S O U R C E L I B R A R Y E N C Y C L O P E D I C E N T RY Australia and Oceania: Physical Geography Encyclopedic entry. Oceania is a region made up of thousands of islands throughout the South Pacific Ocean. G R A D E S 6 - 12+ S U B J E C T S Biology, Earth Science, Geology, Geography, Human Geography, Physical Geography C O N T E N T S 10 Images For the complete encyclopedic entry with media resources, visit: http://www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/oceania-physical-geography/ Oceania is a region made up of thousands of islands throughout the Central and South Pacific Ocean. It includes Australia, the smallest continent in terms of total land area. Most of Australia and Oceania is under the Pacific, a vast body of water that is larger than all the Earth’s continental landmasses and islands combined. The name “Oceania” justly establishes the Pacific Ocean as the defining characteristic of the continent. Oceania is dominated by the nation of Australia. The other two major landmasses of Oceania are the microcontinent of Zealandia, which includes the country of New Zealand, and the eastern half of the island of New Guinea, made up of the nation of Papua New Guinea. Oceania also includes three island regions: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (including the U.S. state of Hawaii). Oceania’s physical geography, environment and resources, and human geography can be considered separately. Oceania can be divided into three island groups: continental islands, high islands, and low islands.