Eupsychian Theory: Reclaiming Maslow and Rejecting the Pyramid - the Seven Essential Needs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healthy Personality

HEALTHY PERSONALITY Presented by CONTINUING PSYCHOLOGY EDUCATION 6 CONTINUING EDUCATION HOURS “I wanted to prove that human beings are capable of something grander than war and prejudice and hatred.” Abraham Maslow, Psychology Today, 1968, 2, p.55. Course Objective Learning Objectives The purpose of this course is to provide an Upon completion, the participant will understand understanding of the concept of healthy personality. the nature, motivation, and characteristics of the Seven theorists offer their views on the subject, healthy personality. Seven influential including: Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, Erich psychotherapists-theorists examine the concept Fromm, Abraham Maslow, Carl Jung, Viktor of healthy personality allowing the reader to Frankl, and Fritz Perls. integrate these principles into his or her own life. Accreditation Faculty Continuing Psychology Education is approved to Neil Eddington, Ph.D. provide continuing education by the following: Richard Shuman, LMFT Texas State Board of Social Worker Examiners (Provider # CS3329) - 5 hours for this course; Texas State Board of Examiners of Professional Counselors (LPC Provider # 2013) - 6 hours for this course; Texas State Board of Examiners of Marriage and Family Therapists - 6 hours for this course; this course meets the qualifications for 6 hours of continuing education for Psychologists, LSSPs, LPAs, and Provisionally Licensed Psychologists as required by the Texas State Board of Examiners of Psychologists. Mission Statement Continuing Psychology Education provides the highest quality continuing education designed to fulfill the professional needs and interests of mental health professionals. Resources are offered to improve professional competency, maintain knowledge of the latest advancements, and meet continuing education requirements mandated by the profession. -

Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory)

Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory) What is the Theory? Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is a theory in psychology proposed by the American psychologist Abraham Maslow in his 1943 paper “A Theory of Human Motivation”. Maslow developed a theory that suggests we are motivated to satisfy five basic needs. These needs are arranged in a hierarchy. Maslow suggests that we seek first to satisfy the lowest level of needs. Once this is done, we seek to satisfy each higher level of need until we have satisfied all five needs. While modern research shows some shortcomings with this theory, Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory remains an important and simple motivation tool for managers to understand and apply. The Hierarchy of Needs is as follows: 1. Physiological Needs (basic issues of survival such as salary, stable employment, able to eat/drink/sleep well) 2. Security Needs (stable physical and emotional environment issues such as benefits, pension, safe work environment, and fair work practices; job security) 3. “Belongingness” Needs (social acceptance issues such as friendship or cooperation on the job; feeling part of a group/team) 4. Esteem Needs (positive self-image and respect and recognition issues such as job titles, nice work spaces, and prestigious job assignments; being recognised for achievements/improvements) 5. Self-Actualization Needs (achievement issues such as workplace autonomy, challenging work, and subject matter expert status on the job, the need for personal growth and development) Extracts taken from https://managementisajourney.com/motivation-applying-maslows-hierarchy-of-needs-theory/ 1 Hierarchy of Needs – Abraham Maslow; 1943 (Content Theory) How to Apply this Theory to the Workplace 1. -

The Transpersonal William James

THE TRANSPERSONAL WILLIAM JAMES Mark B. Ryan, Ph.D. Cholula, Puebla, Mexico ABSTRACT: Transpersonal psychologists often speculate on who was their ‘‘first’’ pioneer, commonly with reference to Carl Jung. A look at the early development of modern psychology, however, reveals various figures who accepted a spiritual and collective dimension of the psyche, among them William James. Out of a tension between scientific and religious outlooks embodied in his own life and thought, James had embraced and articulated the principal elements of a transpersonal orientation by the early twentieth century, and had given them a metaphysical and empirical justification on which they still can stand today. We can see those elements in four aspects of his thought: first, in what he chose to study, especially in his interest in psychic and religious experience; second, in his definition of true science and his refutation of materialism; third, in his concept of consciousness; and fourth, in his defense of the validity of spiritual experience. ‘‘100 Years of Transpersonal Psychology’’: the title and description of the Association for Transpersonal Psychology conference in September, 2006, represented a milestone in the official recognition of William James’s place in the origins of modern transpersonal thought. As the conference’s official announcement declared, James made the first recorded use of the term ‘‘transpersonal’’ in 1905. The conference’s title took its measure of a century from that coinage, suggesting a major role for James in the founding of the field. The occasion of James’s use of the term was modest: an unpublished document, merely a printed course syllabus at Harvard University for an introductorycourse in philosophy (Vich, 1998). -

Who Is Abraham Maslow?

WHO IS ABRAHAM MASLOW? A SHORT READING J WHO IS ABRAHAM MASLOW? • Abraham Maslow was an American psychologist. • Psychology is the scientific study of the mind and behavior. • Best known for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs • He stressed the importance of focusing on the positive qualities of people. • During his time, psychologists were usually focused on the abnormal and ill. • Maslow focused on positive mental health. WHAT IS MASLOW KNOWN FOR? MASLOW’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS • Maslow described that people will be motivated to achieve certain needs, and some needs will take priority over others. • The first need is for physical survival, and that will be what motivates a person’s behavior. • Once that need is met, the next level of needs is what will motivate a person’s behavior. WHAT ARE THE NEEDS? PHYSIOLOGICAL • Most important needs to have met • Biological requirements for human survival • air, food, drink, shelter, clothing, warmth, sex, sleep SAFETY • People want to experience order, predictability and control in their lives. • These needs can be fulfilled by the family and society • Police, schools, business and medical care LOVE AND BELONGINGNESS • The third level of human needs is social and involves feelings of belongingness. The need for interpersonal relationships motivates behavior. • Examples include friendship, intimacy, trust, and acceptance, receiving and giving affection and love. Affiliating, being part of a group (family, friends, work). ESTEEM • The fourth level in Maslow’s hierarchy - which Maslow classified into two categories: 1. esteem for oneself (dignity, achievement, mastery, independence) and 2. the desire for reputation or respect from others (status, prestige). -

Challenges of Humanistic Psychology for Secondary Education Walter P

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 7-1972 Challenges of Humanistic Psychology for Secondary Education Walter P. Dember Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Education Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHALLENGES OF HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY FOR SECONDARY EDUCATION By Walter P. Dember B.B.A., St. Bo11aventu.re University, 19.52 M.S., Niagara University, 1970 ~ ! ' ' ,.1. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Walden University July, 1972 ~~-· ., . ABSTRACT CHALLENGES OF HUMANISTIC P&"YCHOLOGY FOR SECONDARY EDUCATION By Walter P. Dember E.B.A., St. Bonaventure University, 1952 M.S., Niagara University, 1970 Frederick C. Spei , Ed. D., Advisor School Administrator, Buffalo Public Schools Buffalo, New York A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Walden University July, 1972 ----~-----..,.------------------------.....·-::r, • ABSTRACT CHALLENGES OF HUMANISTIC PSYCHOLOGY FOR SECONDARY EDUCATION A new conception of man is now being unfolded in a very different orientation toward p~chology or in a new p~chology called "Humanistic Psychology." It is the purpose of this thesis to arrive at these new concepts of man through research into the writings of and about four hnma:nistic p~chologists--Gordon W. -

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs in an Inclusion Classroom- by Kaitlin Lutz

Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs in an Inclusion Classroom- By Kaitlin Lutz (/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom- +By+Kaitlin+Lutz) # Edit ! 0 (/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz#discussion) " 3 (/page/history/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz) … (/page/menu/Maslow%27s+Hierarchy+of+Needs+in+an+Inclusion+Classroom-+By+Kaitlin+Lutz) All students have basic needs to be met for learning to occur. The more needs that are met, the more students will learn. Maslow's hierarchy, developed by Abraham Maslow in 1954, is a way of organizing the basic needs of students on different levels (McLeod, 2007). The more levels that are met, the more a student will learn. Maslow's hierarchy of needs applies especially to students with exceptionalities, because many times students' with exceptionalities needs are more difficult to meet. Abraham Maslow http://thesocialworkexam.com/maslows-theory-of-basic-needs-learning What is Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs? According to Gorman in the Aboriginal and Islander Health Worker Journal, there are six levels to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. The first level is physiological needs. The first level must be met in order to move onto any other levels in the hierarchy. Physiological needs include the basic necessities of life (Gorman, 2010). These needs may include food, water, and shelter. Once physiological needs are met, students will then need the second level of Maslow's hierarchy. The second level is safety needs. Students need to feel safe in the environment in which they are learning with no outside threats. -

Download Article (PDF)

2013 International Conference on Advances in Social Science, Humanities, and Management (ASSHM 2013) The Beauty of the Transcending of the Humanity --Research on Maslow’s Self-actualization Theory Liu Hongyu1 Han Lu2 1The School of Psychology and Cognitive Science of East China Normal Unversity 2The School of Art and Design of Wuhan Textile University Abstract: but also the highest value goal of the entire Abraham Harold Maslow is a world-renowned psychology and ethics. Maslow's psychology social psychologist, personality theorist and an and ethics are built around one center, i.e., man expert at comparative psychology. Maslow has or humanity. It is human-centered and based on also made great achievements in philosophy and humans’ needs with full realization of human literature. potential as its final goal. Maslow's theory can Maslow is a well-known scholars with his be expressed by a simple formula: human → study of self-realization in the West.The concept need (motivation) →behavior → realization of of self-realization is complex and rich in value or humanity (self-actualization is the connotation.He completed the research on the vertex). Maslow suggests that self-actualization self-fulfilling the original intention of those who is based on people's needs system rooted in are very specific,such as,to identify human genetic gene like instinct, namely the intrinsic beings,to make outstanding contributions to requirement of the realization of five needs society of people of common personality (physiology, safety, love/belonging, self-esteem, characteristics,to identify some of the positive self-actualization) from the bottom to the top, human potential value of the goal. -

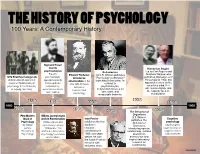

02B Psych Timeline.Pages

THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY 100 Years: A Contemporary History Sigmund Freud founds Humanism Begins psychoanalysis Behaviorism Led by Carl Rogers and Freud's Edward Titchener John B. Watson publishes Abraham Maslow, who 1879 First Psychology Lab psychoanalytic introduces "Psychology as Behavior," publishes Motivation and Personality in 1954, this Wilhelm Wundt opens first approach asserts structuralism in the launching behaviorism. In experimental laboratory in that people are contrast to approach centers on the U.S. with his book conscious mind, free psychology at the University motivated by, Manual of psychoanalysis, of Leipzig, Germany. unconscious drives behaviorism focuses on will, human dignity, and Experimental the capacity for self- and conflicts. observable and Psychology measurable behavior. actualization. 1938 1890 1896 1906 1956 1860 1960 1879 1901 1913 The Behavior of 1954 Organisms First Modern William James begins B.F. Skinner Ivan Pavlov Cognitive Book of work in Functionalism publishes The Psychology William James and publishes the first Behavior of psychology By William John Dewey, whose studies in Organisms, psychologists James, 1896 article "The classical introducing operant begin to focus on Principles of Reflex Arc Concept in conditioning in conditioning. It draws cognitive states Psychology Psychology" promotes 1906; two years attention to and processes functionalism. before, he won behaviorism and the Nobel Prize for inspires laboratory his work with research on salivating dogs. conditioning. Name _________________________________Date _________________Period __________ THE HISTORY OF PSYCHOLOGY A Contemporary History Use the timeline from the back to answer the questions. 1. What happened earlier? A) B.F. Skinner publishes The Behavior of Organism B) John B. Watson publishes Psychology as Behavior 2. -

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory

December 15, 2008 Perspectives in Theory: Anthology of Theorists affecting the Educational World Editors: Misty M. Bicking, Brian Collins, Laura Fernett, Barbara Taylor, Kathleen Sutton Shepherd University Table Of Contents Abstract_______________________________________________________________________4 Alfred Adler ___________________________________________________________________5 Melissa Bartlett Mary Ainsworth _______________________________________________________________17 Misty Bicking Alois Alzheimer _______________________________________________________________30 Maura Bird Albert Bandura ________________________________________________________________45 Lauren Boyer James A. Banks________________________________________________________________59 Adel D. Broadwater Vladimir Bekhterev_____________________________________________________________72 Thomas Cochrane Benjamin Bloom_______________________________________________________________86 Brian Collins John Bowlby and Attachment Theory ______________________________________________98 Colin Curry Louis Braille: Research_________________________________________________________111 Justin Everhart Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model___________________________________________124 Kristin Ezzell Jerome Bruner________________________________________________________________138 Laura Beth Fernett Noam Chomsky Stubborn Without________________________________________________149 Jamin Gibson Auguste Comte _______________________________________________________________162 Heather Manning -

Abraham Maslow

ABRAHAM MASLOW 1908-1970 Dr. C. George Boeree Maslow (in French, translated by Silvia Moraru) Маслоу (in Belarussian) Biography Abraham Harold Maslow was born April 1, 1908 in Brooklyn, New York. He was the first of seven children born to his parents, who themselves were uneducated Jewish immigrants from Russia. His parents, hoping for the best for their children in the new world, pushed him hard for academic success. Not surprisingly, he became very lonely as a boy, and found his refuge in books. To satisfy his parents, he first studied law at the City College of New York (CCNY). After three semesters, he transferred to Cornell, and then back to CCNY. He married Bertha Goodman, his first cousin, against his parents wishes. Abe and Bertha went on to have two daughters. He and Bertha moved to Wisconsin so that he could attend the University of Wisconsin. Here, he became interested in psychology, and his school work began to improve dramatically. He spent time there working with Harry Harlow, who is famous for his experiments with baby rhesus monkeys and attachment behavior. He received his BA in 1930, his MA in 1931, and his PhD in 1934, all in psychology, all from the University of Wisconsin. A year after graduation, he returned to New York to work with E. L. Thorndike at Columbia, where Maslow became interested in research on human sexuality. He began teaching full time at Brooklyn College. During this period of his life, he came into contact with the many European intellectuals that were immigrating to the US, and Brooklyn in particular, at that time -- people like Adler, Fromm, Horney, as well as several Gestalt and Freudian psychologists. -

Major Schools of Thought in Psychology

Major Schools of Thought in Psychology When psychology was first established as a science separate from biology and philosophy, the debate over how to describe and explain the human mind and behavior began. The first school of thought, structuralism, was advocated by the founder of the first psychology lab, Wilhelm Wundt . Almost immediately, other theories began to emerge and vie for dominance in psychology. The following are some of the major schools of thought that have influenced our knowledge and understanding of psychology: Structuralism vs. Functionalism: Structuralism was the first school of psychology, and focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components. Major structuralist thinkers include Wilhelm Wundt and Edward Titchener. Functionalism formed as a reaction to the theories of the structuralist school of thought and was heavily influenced by the work of William James . Major functionalist thinkers included John Dewey and Harvey Carr. Behaviorism: Behaviorism became the dominant school of thought during the 1950s. Based upon the work of thinkers such as John B. Watson , Ivan Pavlov , and B. F. Skinner , behaviorism holds that all behavior can be explained by environmental causes, rather than by internal forces. Behaviorism is focused on observable behavior . Theories of learning including classical conditioning and operant conditioning were the focus of a great deal of research. Psychoanalysis : Sigmund Freud was the found of psychodynamic approach. This school of thought emphasizes the influence of the unconscious mind on behavior. Freud believed that the human mind was composed of three elements: the id , the ego , and the superego. Other major psychodynamic thinkers include Anna Freud, Carl Jung, and Erik Erikson. -

A Brief Analysis of Abraham Maslow's Original Writing of Self-Actualizing People

DOCTORAL FORUM NATIONAL JOURNAL OF PUBLISHING AND MENTORING DOCTORAL STUDENT RESEARCH VOLUME 3, NUMBER 1, 2006 A Brief Analysis of Abraham Maslow’s Original Writing of Self-Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health Nedra H. Francis, MA, LPA, LSSP William Allan Kritsonis, PhD Doctoral Student Professor Clinical Adolescent Psychology PhD Program in Educational Leadership College of Juvenile Justice and Psychology Prairie View A&M University Prairie View A&M University Member of the Texas A&M University System Visiting Lecturer (2005) Oxford Round Table University of Oxford, Oxford, England Distinguished Alumnus (2004) Central Washington University College of Education and Professional Studies ABSTRACT This article analyzes Abraham Maslow’s original writing of Self-Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health. The review of literature in this article reveals that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs have had profound effects in the area of psychology. In addition, the authors present information regarding self-actualized people, theorists of psychology, humanistic principles, culture, and other related issues. he purpose of this article is to briefly discuss Abraham Maslow’s original writing of Self- Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health. Maslow’s work is discussed T relative to his work on psychology, implications of work, research, culture, ethnicities, children, issues, gender, theoretical assumptions, and impact on psychology in the United States. 1 DOCTORAL FORUM NATIONAL JOURNAL OF PUBLISHING AND MENTORING DOCTORAL STUDENT RESEARCH 2________________________________________________________________________________________ Self-Actualizing People: A Study of Psychological Health Abraham Maslow was one of the greatest psychologists of our times. He was best known for the development of his theory on Self-Actualization (SA) and/or Hierarchy of Needs.