Suzie Dobrontei Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU and Member States' Policies and Laws on Persons Suspected Of

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS’ RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS EU and Member States’ policies and laws on persons suspected of terrorism- related crimes STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee), presents an overview of the legal and policy framework in the EU and 10 select EU Member States on persons suspected of terrorism-related crimes. The study analyses how Member States define suspects of terrorism- related crimes, what measures are available to state authorities to prevent and investigate such crimes and how information on suspects of terrorism-related crimes is exchanged between Member States. The comparative analysis between the 10 Member States subject to this study, in combination with the examination of relevant EU policy and legislation, leads to the development of key conclusions and recommendations. PE 596.832 EN 1 ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and was commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation -

Group Support and Cognitive Dissonance 1 I'ma

Group support and cognitive dissonance 1 I‘m a Hypocrite, but so is Everyone Else: Group Support and the Reduction of Cognitive Dissonance Blake M. McKimmie, Deborah J. Terry, Michael A. Hogg School of Psychology, University of Queensland Antony S.R. Manstead, Russell Spears, and Bertjan Doosje Department of Social Psychology, University of Amsterdam Running head: Group support and cognitive dissonance. Key words: cognitive dissonance, social identity, social support Contact: Blake McKimmie School of Psychology The University of Queensland Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia Phone: +61 7 3365-6406 Fax: +61 7 3365-4466 Group support and cognitive dissonance 2 [email protected] Abstract The impact of social support on dissonance arousal was investigated to determine whether subsequent attitude change is motivated by dissonance reduction needs. In addition, a social identity view of dissonance theory is proposed, augmenting current conceptualizations of dissonance theory by predicting when normative information will impact on dissonance arousal, and by indicating the availability of identity-related strategies of dissonance reduction. An experiment was conducted to induce feelings of hypocrisy under conditions of behavioral support or nonsupport. Group salience was either high or low, or individual identity was emphasized. As predicted, participants with no support from the salient ingroup exhibited the greatest need to reduce dissonance through attitude change and reduced levels of group identification. Results were interpreted in terms of self -

Institutional Abuse: a Psychiatrist's Perspective

Institutional Abuse: Untying the Gordian Knot Dr Julian Parmegiani MB BS FRANZCP September 2018 Out of Home Care – Current Statistics Heritability of Psychiatric Disorders The effects of trauma during childhood and adolescence Talk Snowballing Effects of Trauma Outline Protective Factors and Resilience False Memories Impact of legal proceedings Children subjected to investigation = 115,024 Substantiated = 45,714 Child Protection Children on care & Services – protection orders = 61,723 Children in out-of-home care = 2016 55,614 *AIHW Child Protection Report 2015-2016 Child Protection Services – Statistics Type of Abuse Primary + other abuse Emotional Abuse 43% 32.5% Neglect 27% 28.2% Physical Abuse 18% 15% Sexual Abuse 12% 1.7% *AIHW Child Protection Report 2015-2016 Out-of-home care • 46% under 5yrs old Child • 94% in home-based care – 49% in relative/kinship care Protection – 39% in foster care – 5% in third party parental care Services – – 1% other Statistics • 6% in institutions *AIHW Child Protection Report 2015-2016 No information about the parents – possible reasons: Child • Alcohol abuse Protection • Drug abuse • Mental illness Services – • Severe personality disorder Statistics • In custody • Cognitive impairment • Genetic vulnerability – Mental illness might have manifested itself anyway • Pre-existing behavioural problems – Parents couldn’t cope with uncontrollable child • Psychological trauma might have already caused irreparable damage before being Evaluation taken into institution • Targeting: Bullies and predators victimizing of Adult vulnerable targets – Odd – Socially inadequate Survivors – Shy – Anxious – Depressed • All of the above combined MJA • Volume 185 Number 9 • 6 November 2006 MJA • Volume 185 Number 9 • 6 November 2006 MJA • Volume 185 Number 9 • 6 November 2006 Alcohol Use Disorder - 50% heritable The heritability of alcohol use disorders: a Heritability meta-analysis of twin and adoption studies B. -

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated With

Polarized Ukraine 2014: Opinion and Territorial Split Demonstrated with the Bounded Confidence XY Model, Parameterized by Twitter Data Maksym Romenskyy Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK and Department of Mathematics, Uppsala University, Box 480, Uppsala 75106, Sweden Viktoria Spaiser School of Politics and International Studies, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK Thomas Ihle Institute of Physics, University of Greifswald, Felix-Hausdorff-Str. 6, Greifswald 17489, Germany Vladimir Lobaskin School of Physics, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland (Dated: July 26, 2018) Multiple countries have recently experienced extreme political polarization, which in some cases led to escalation of hate crime, violence and political instability. Beside the much discussed presi- dential elections in the United States and France, Britain’s Brexit vote and Turkish constitutional referendum, showed signs of extreme polarization. Among the countries affected, Ukraine faced some of the gravest consequences. In an attempt to understand the mechanisms of these phe- nomena, we here combine social media analysis with agent-based modeling of opinion dynamics, targeting Ukraine’s crisis of 2014. We use Twitter data to quantify changes in the opinion divide and parameterize an extended Bounded-Confidence XY Model, which provides a spatiotemporal description of the polarization dynamics. We demonstrate that the level of emotional intensity is a major driving force for polarization that can lead to a spontaneous onset of collective behavior at a certain degree of homophily and conformity. We find that the critical level of emotional intensity corresponds to a polarization transition, marked by a sudden increase in the degree of involvement and in the opinion bimodality. -

Appendix 3 Chronology of Events Surrounding Increased Security

Appendix 3 Chronology of events surrounding increased security measures Notable European terror related incidents • Nov 2015 – Paris Attacks. 130 killed and 413 injured by suicide bombers and mass shootings • March 2016 – Brussels Bombing. 35 killed and 300 injured by suicide bomber • July 2016 – Nice attacks. 86 killed and 458 injured by a cargo truck driven into crowds • Dec 2016 – Berlin Xmas market attack. 12 killed and 56 injured by a truck driven into crowds • Aug 2017 – Barcelona attack. 13 killed and 130 injured by truck driven into crowds Recent British terror related incidents • May 2013 A British soldier, Lee Rigby, was murdered in an attack by two Islamist extremists • June 2016 MP Jo Cox murdered by white nationist • March 2017 Westminster attack - Islamist, drove a car into pedestrians on Westminster Bridge. 4 killed and 50 injured. A police officer killed in the grounds of the Palace of Westminster • May 2017 Manchester Arena bombing – An Islamist suicide bomber, blew himself up at Manchester Arena, 22 killed and 139 injured • June 2017 London Bridge attack – Three Islamists drove a van into pedestrians on London bridge before stabbing. Eight people were killed and at least 48 wounded • June 2017 Finsbury Park attack –a British man, drove a van into Muslim worshippers near Finsbury Park Mosque, London Recent Guildhall security related incidents. Evidence cycle thefts and anti-social related incidents surrounding rough sleepers in the area that have not formally been reported. • Feb 2014 - Planned demonstration at full council. Demonstration prevented by joint operation between Facilities and Police to monitor building access. • Feb 2015 – Planned demonstration at full council. -

Lecture Misinformation

Quote of the Day: “A lie will go round the world while truth is pulling its boots on.” -- Baptist preacher Charles H. Spurgeon, 1859 Please fill out the course evaluations: https://uw.iasystem.org/survey/233006 Questions on the final paper Readings for next time Today’s class: misinformation and conspiracy theories Some definitions of fake news: • any piece of information Donald Trump dislikes more seriously: • “a type of yellow journalism or propaganda that consists of deliberate disinformation or hoaxes spread via traditional news media (print and broadcast) or online social media.” disinformation: “false information which is intended to mislead, especially propaganda issued by a government organization to a rival power or the media” misinformation: “false or inaccurate information, especially that which is deliberately intended to deceive” Some findings of recent research on fake news, disinformation, and misinformation • False news stories are 70% more likely to be retweeted than true news stories. The false ones get people’s attention (by design). • Some people inadvertently spread fake news by saying it’s false and linking to it. • Much of the fake news from the 2016 election originated in small-time operators in Macedonia trying to make money (get clicks, sell advertising). • However, Russian intelligence agencies were also active (Kate Starbird’s research). The agencies created fake Black Lives Matter activists and Blue Lives Matter activists, among other profiles. A quick guide to spotting fake news, from the Freedom Forum Institute: https://www.freedomforuminstitute.org/first-amendment- center/primers/fake-news-primer/ Fact checking sites are also essential for identifying fake news. -

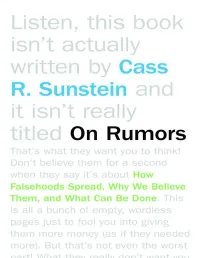

On Rumors Also by Cass R

On Rumors Also by Cass R. Sunstein Simpler: The Future of Government Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard Thaler) Worst-Case Scenarios Republic.com 2.0 Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge The Second Bill of Rights: Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Unfinished Revolution and Why We Need It More Than Ever Radicals in Robes: Why Extreme Right-Wing Courts Are Wrong for America Laws of Fear: Beyond the Precautionary Principle Why Societies Need Dissent Risk and Reason: Safety, Law, and the Environment One Case at a Time Free Markets and Social Justice Legal Reasoning and Political Conflict Democracy and the Problem of Free Speech The Partial Constitution After the Rights Revolution On Rumors How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, and What Can Be Done Cass R. Sunstein With a new afterword by the author Princeton University Press • Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2014 by Cass R. Sunstein Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Originally published in North America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2009 First Princeton Edition 2014 ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-16250-8 LCCN 2013950544 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Printed on acid-free paper. -

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration

Varieties of Opinion Change in a Finnish Citizen Deliberation Experiment on Immigration Marina Lindell (Åbo Akademi University), André Bächtiger (University of Stuttgart), Kimmo Grönlund (Åbo Akademi University), Kaisa Herne (University of Tampere), Maija Setälä (University of Turku) Abstract In the study of deliberation, a largely underexplored area is why some participants become more extreme, whereas some become more moderate. Opinion polarization is usually considered a suspicious outcome of deliberation, while moderation is seen as a desirable one. This article takes issue with this view. Results from a deliberative experiment on immigration show that polarizers and moderators were not different in their socio-economic, cognitive, or affective profiles. Moreover, both polarization and moderation can entail deliberatively desired pathways: in the experiment, both polarizers and moderators learned during deliberation, levels of empathy were fairly high on both sides, and group pressures barely mattered. Finally, the absence of a participant with an immigrant background in a group was associated with polarization in anti-immigrant direction, bolstering longstanding claims regarding the importance of presence in interaction (Philips 1995). Paper presented at the “13ème Congrès National Association Française de Science Politique (AFSP), Aix-en-Provence, June 22–24, 2015 1 Introduction Empirical studies of citizen deliberation suggest that participants often change opinions (and also quite radically; see, e.g., Fishkin, 2009). Luskin et al. (2002) claim that knowledge gain is an important mechanism of opinion change, whereas Sanders (2012) was unable to identify any robust predictor of opinion change in a recent study based on a pan-European deliberative poll (Europolis). A largely understudied area in this regard is why some participants polarize their opinions due to deliberation, and why others moderate them. -

The Locus of Control

UVA-OB-0786 THE LOCUS OF CONTROL Please check true or false to the statements below that best fit your own beliefs. Please do so before reading the rest of this note. Locus of Control Instrument1 TRUE FALSE 1. I usually get what I want in life. 2. I need to be kept informed about news events. 3. I never know where I stand with other people. 4. I do not really believe in luck or chance. 5. I think that I could easily win a lottery. 6. If I do not succeed on a task, I tend to give up. 7. I usually convince others to do things my way. 8. People make a difference in controlling crime. 9. The success I have is largely a matter of chance. 10. Marriage is largely a gamble for most people. 11. People must be the master of their own fate. 12. It is not important for me to vote. 13. My life seems like a series of random events. 14. I never try anything that I am not sure of. 15. I earn the respect and honors I receive. 16. A person can get rich by taking risks. 17. Leaders are successful when they work hard. 18. Persistence and hard work usually lead to success. 19. It is difficult to know who my real friends are. 20. Other people usually control my life. 1 A professor in the psychology department at Mercyhurst College in Erie, Pennsylvania, Terry Pettijohn developed this variation to Rotter’s original Locus of Control survey. This technical note was written by Gerry Yemen and James G. -

Affective Polarization and Its Impact on College Campuses

Bucknell University Bucknell Digital Commons Honors Theses Student Theses Spring 2020 Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses Sam Rosenblatt Bucknell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses Part of the American Politics Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rosenblatt, Sam, "Can We All Just Get Along?: Affective Polarization and its Impact on College Campuses" (2020). Honors Theses. 529. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/honors_theses/529 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Bucknell Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Bucknell Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAN WE ALL JUST GET ALONG?: AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION AND ITS IMPACT ON COLLEGE CAMPUSES by Sam Rosenblatt A Thesis Submitted to the Honors Council For Honors in Political Science April 3, 2020 Approved by: _____________________________________ Advisor: Chris Ellis _____________________________________ Department Chairperson: Scott Meinke Acknowledgements While the culmination of my honors thesis feels a bit anticlimactic as Bucknell has transitioned to remote education, I could not have accomplished this project without the help of the many faculty, friends, and family who supported me. To Professor Ellis, thank you for advising and guiding me throughout this process. Your advice was instrumental and I looked forward every week to discussing my progress and American politics with you. To Professor Meinke and Professor Stanciu, thank you for serving as additional readers. And especially to Professor Meinke for helping to spark my interest in politics during my freshman year. -

Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster

2008 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster Report Submitted to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, Pittsburgh Research Laboratory George S. Everly, Jr., PhD, ABPP Paul Perrin & George S. Everly, III Contents INTRODUCTION THE PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACT OF CRISIS AND DISASTERS The Nature of Human Stress Physiology of Stress Psychology of Stress Excessive Stress Distress Depression Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Compassion Fatigue A Review of Empirical Investigations on the Mental Health Consequences of Crisis and Disaster Primary Victims/ Survivors Rescue and Recovery Personnel “RESISTANCE, RESILIENCE, AND RECOVERY” AS A STRATEGIC AND INTEGRATIVE INTERVENTION PARADIGM Historical Foundations Resistance, Resiliency, Recovery: A Continuum of Care Building Resistance Self‐efficacy Hardiness Enhancing Resilience Fostering Recovery LEADERSHIP AND THE INCIDENT MANAGEMENT AND INCIDENT COMMAND SYSTEMS (ICS) Leadership: What is it? Leadership Resides in Those Who Follow Incident Management Essential Information NIMS Components 1 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster | George Everly, Jr. The Need for Incident Management Key Features of the ICS Placement of Psychological Crisis Intervention Teams in ICS Functional Areas in the Incident Command System Structuring the Mental Health Response Challenges of Rural and Isolated Response Caution: Fatigue in Incident Response Summary CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS REFERENCES APPENDIX A – Training resources in disaster mental health and crisis intervention APPENDIX B – Psychological First Aid (PFA) 2 Psychological Issues in Escape, Rescue, and Survival in the Wake of Disaster | George Everly, Jr. Introduction The experience of disaster appears to have become an expected aspect of life. Whether it is a natural disaster such as a hurricane or tsunami, or a human‐made disaster such as terrorism, the effects can be both physically and psychological devastating. -

Self-Regulation of Driving by Older Adults a Longroad Study

Seniors face serious driving safety and mobility issues. Self-Regulation of Driving by Older Adults A LongROAD Study December 2015 607 14th Street, NW, Suite 201 | Washington, DC 20005 | AAAFoundation.org | 202-638-5944 Title Self-Regulation of Driving by Older Adults: A Synthesis of the Literature and Framework for Future Research. (December 2015) Author Lisa J. Molnar1,2, David W. Eby1,2, Liang Zhang1,2,3, Nicole Zanier1,2, Renée M. St. Louis1,2, Lidia P. Kostyniuk1,2 1University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI) 2Center for Advancing Transportation Leadership and Safety (ATLAS Center) 3Tsinghua University, Beijing, China Acknowledgments This publication was produced as part of the LongROAD (Longitudinal Research on Aging Drivers) Study, a collaborative cohort study of aging and driving managed by Columbia University (Dr. Guohua Li, PI), the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (Dr. David W. Eby, Co-PI), and the Urban Institute (Mr. Robert Santos, Co-PI). Other institutions participating in the project are: University of Michigan Institute for Social Research; University of Michigan Geriatrics Center; University of Colorado School of Medicine; University of Colorado School of Public Health; Johns Hopkins University; Bassett Research Institute; and the University of California, San Diego Department of Family and Preventative Medicine. Liang Zhang’s effort on this report was supported by the China Scholarship Council, a non-profit institution with legal person status affiliated with the Chinese Ministry of Education which funded Liang Zhang as a visiting scholar at the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute (UMTRI), and the ATLAS Center, a University Transportation Center sponsored by the U.S.