Exploring Relationships Between Time, Law and Social Ordering: a Curated Conversation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. -

Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock

Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock (ETC) for Assistance Provided to Other Routes WHEN PROVIDING OFFICE ASSISTANCE Press "MOVE" Press "OFFICE" Type in the number of the route that your are assisting. This will be a six digit number that begins with 0 followed by the last two numbers of the zip code for that route and then one or two zeros and the number of the route. Example for route 2 in the 20886 zip code would be 086002 Route 15 in the 20878 zip code would be 078015 Then swipe your badge WHEN YOU HAVE FINISHED PROVIDING OFFICE ASSISTANCE Press "MOVE" Press "OFFICE" Type in the number of the route you are assigned to that day (as above) Swipe your badge WHEN PROVIDING STREET ASSISTANCE AND ENTERING THE INFORMATION WHEN YOU RETURN FROM THE STREET Press "MOVE" Press "STREET" Type in the number of the route that you assisted (as above) Type in the time that you started to provide assistance in decimal hours (3:30 would be 1550). See the conversion chart. Swipe your badge Press "MOVE" Press "STREET" Type in YOUR route number (as above) Type in the time you finished providing assistance to the other route, Swipe your badge Page 1 TIME CONVERSION TABLE Postal timekeepers use a combination of military time (for the hours) and decimal time (for the minutes). Hours in the morning need no conversion, but use a zero before hours below 10; to show evening hours, add 12. (Examples: 6:00 am = 0600; 1:00 pm = 1300.) Using this chart, convert minutes to fractions of one hundred. -

Alasdair Gray and the Postmodern

ALASDAIR GRAY AND THE POSTMODERN Neil James Rhind PhD in English Literature The University Of Edinburgh 2008 2 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by me; that it is entirely my own work, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified on the title page. Signed: Neil James Rhind 3 CONTENTS Title……………………………………….…………………………………………..1 Declaration……………………………….…………………………………………...2 Contents………………………………………………………………………………3 Abstract………………………………….………………………………..…………..4 Note on Abbreviations…………………………………………………………….….6 1. Alasdair Gray : Sick of Being A Postmodernist……………………………..…….7 2. The Generic Blending of Lanark and the Birth of Postmodern Glasgow…….…..60 3. RHETORIC RULES, OK? : 1982, Janine and selected shorter novels………….122 4. Reforming The Victorians: Poor Things and Postmodern History………………170 5. After Postmodernism? : A History Maker………………………………………….239 6. Conclusion: Reading Postmodernism in Gray…………………………………....303 Endnotes……………………………………………………………………………..320 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….324 4 ABSTRACT The prominence of the term ‘Postmodernism’ in critical responses to the work of Alasdair Gray has often appeared at odds with Gray’s own writing, both in his commitment to seemingly non-postmodernist concerns and his own repeatedly stated rejection of the label. In order to better understand Gray’s relationship to postmodernism, this thesis begins by outlining Gray’s reservations in this regard. Principally, this is taken as the result of his concerns -

(Loadest): a Fortran Program for Estimating Constituent Loads in Streams and Rivers

LOAD ESTIMATOR (LOADEST): A FORTRAN PROGRAM FOR ESTIMATING CONSTITUENT LOADS IN STREAMS AND RIVERS Techniques and Methods Book 4, Chapter A5 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Load Estimator (LOADEST): A FORTRAN Program for Estimating Constituent Loads in Streams and Rivers By Robert L. Runkel, Charles G. Crawford, and Timothy A. Cohn Techniques and Methods Book 4, Chapter A5 U.S. Department of the Interior! U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2004 For more information about the USGS and its products:! Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS! World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply ! endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, it contains copyrighted materials that are noted in the text. ! Permission to reproduce those items must be secured from the individual copyright owners. iii Contents Abstract . .. 1 1 Introduction . 2 1.1 Background . 2 1.2 Related Reading . 2 1.3 Report Organization . 2 1.4 Acknowledgments . .. 2 2 Theory . 3 2.1 Background – Linear Regression Approach to Load Estimation . 3 2.2 Load Estimation Methods used within LOADEST . 4 2.2.1 Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) . 5 2.2.2 Adjusted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (AMLE) . 5 2.2.3 Least Absolute Deviation (LAD) . 6 2.2.4 Summary of MLE, AMLE, and LAD for Load Estimation . -

SAS® Dates with Decimal Time John Henry King, Ouachita Clinical Data Services, Inc., Caddo Gap, AR

Paper RF03-2015 SAS® Dates with Decimal Time John Henry King, Ouachita Clinical Data Services, Inc., Caddo Gap, AR ABSTRACT Did you know that a SAS-Date can have a decimal part that SAS treats as you might expect a fraction of a day also known as time? Often when data are imported from EXCEL an excel date-time will be imported as SAS-Date with a decimal part. This Rapid Fire tip discusses how to identify these values and gives examples of how to work with them including how to convert them to SAS-Date-time. INTRODUCTION A SAS-Date is defined as an integer number representing the number of days since 01JAN1960. For 01JAN1960 the internal SAS Date value is zero. The numeric value stored as Real Binary Floating Point can include a decimal portion and this decimal portion can represent time. For example the SAS-Date 0.5 can be considered to represent ½ day since 01JAN1960 or 01JAN1960:12:00:00. It is important to remember that for the most part SAS ignores the decimal portion and a SAS Date with a decimal value is NOT a SAS-Date-time value. USUALLY IGNORED As shown by this example SAS usually ignores the decimal part. Notice that for SAMEDAY alignment INTNX keeps the decimal part while alignment END and BEGIN drop it. data _null_; x = .5; put x= x=date9.; do align='B','E','S'; i = intnx('week',x,0,align); put i= i=date9. i=weekdate. align=; end; run; x=0.5 x=01JAN1960 i=-5 i=27DEC1959 i=Sunday, December 27, 1959 align=B i=1 i=02JAN1960 i=Saturday, January 2, 1960 align=E i=0.5 i=01JAN1960 i=Friday, January 1, 1960 align=S CONVERSION TO DATE-TIME Converting a SAS-Date with decimal time part to SAS-Date-Time can be done using DHMS function specifying 0 for the hour, minute, and second arguments. -

Stephen Mihm Associate Professor of History University of Georgia 7 November 2014

THE STANDARDS OF THE STATE: WEIGHTS, MEASURES, AND NATION MAKING IN THE EARLY AMERICAN REPUBLIC Stephen Mihm Associate Professor of History University of Georgia 7 November 2014 “State Formations: Histories and Cultures of Statehood” Center for Historical Research at the Ohio State University Do Not Cite or Quote without Permission In January 1830, a committee appointed by the Delaware House of Representatives filed a report to the larger General Assembly. The committee, created in response to a petition praying that the Delaware state government do something to establish “uniform weights and measures,” deemed it “inexpedient to make any legislative enactment upon this subject.” Their argument for inaction, laid out in great detail, reveals something about the fault lines of federalism at this time. “Congress alone can remedy the evils under which we labor, for want of a uniform standard,” they observed: Article I, Section 8 of the United States Constitution explicitly gave Congress the power to “fix the standard of weights and measures.” But Congress, while possessor of this prerogative, had declined to act, despite entreaties to do so. The committee ruefully reported that while “a great variety of useful and curious learning has been developed” as Congress grappled with the problem, “no law has yet been enacted by that body, to fix that standard.” The individual states, the committee reported, had acted, despite the questionable constitutionality of doing so. Each established their own weights and measures, driven by whatever their “particular circumstances seemed to require.” As a consequence, observed the committee, “scarcely any two States agree in their standards of weights and measures.” A small state like Delaware, overshadowed by the large commercial cities of Baltimore and Philadelphia, followed at least two – and likely many more – sets of standards, all of them at variance with each other. -

Time, Timetables & Speed

G.07 G.05 Time, Timetables & Speed Questions involving time are often badly answered in GCSE exams. This is because students use non-calculator addition and subtraction methods learned for use with the decimal number system (H, T, U, etc) with time. This follows a different number system (60 sec in 1 minute, 60 min in 1 hour, 24 hours in 1 day, etc), so methods involving ‘carrying’ and ‘borrowing’ don’t work in the same way. For example, in decimal o I buy two items costing £6.53 and £1.48, how much have I spent? o How much change do I get from £10 But in time o If it is 0653 now, what time will it be in 1 hour and 48 minutes? o and how much time will then elapse until 1000? G.07 G.05 When working with time questions, drawing a time line is often helpful. If the question allows you to use a calculator, learn to use the time button So for the previous question the button presses would be: 6 53 + 1 48 = and 10 0 - 8 41 = GCSE Maths Paper 2 PPQ (Calc OK) G.07 G.05 GCSE Numeracy Paper 2 PPQ (Calc OK) G.07 G.05 Timetables Often appear on a non-calculator paper. Use a timeline and if the journey has more than one stage DO NOT ASSUME they move directly from one stage to another without time passing waiting for the next departure. GCSE Maths Paper 1 PPQ (non-Calc) GCSE Maths Paper 1 PPQ (non-Calc) G.07 G.05 G.07 G.05 Time Zones GCSE Numeracy Paper 1 PPQ (non-Calc) G.07 G.05 G.07 G.05 Average Speed and Decimal Time Another aspect where things go wrong! For example Write 4 hours 15 minutes as a decimal value If this is asked on a Paper 2, once again the time button is your friend! The button presses would be 4 15 = Then pressing again will turn the time to decimal and back again as you repeatedly press the button. -

Julian Day from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia "Julian Date" Redirects Here

Julian day From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia "Julian date" redirects here. For dates in the Julian calendar, see Julian calendar. For day of year, see Ordinal date. For the comic book character Julian Gregory Day, see Calendar Man. Not to be confused with Julian year (astronomy). Julian day is the continuous count of days since the beginning of the Julian Period used primarily by astronomers. The Julian Day Number (JDN) is the integer assigned to a whole solar day in the Julian day count starting from noon Greenwich Mean Time, with Julian day number 0 assigned to the day starting at noon on January 1, 4713 BC, proleptic Julian calendar (November 24, 4714 BC, in the proleptic Gregorian calendar),[1] a date at which three multi-year cycles started and which preceded any historical dates.[2] For example, the Julian day number for the day starting at 12:00 UT on January 1, 2000, was 2,451,545.[3] The Julian date (JD) of any instant is the Julian day number for the preceding noon in Greenwich Mean Time plus the fraction of the day since that instant. Julian dates are expressed as a Julian day number with a decimal fraction added.[4] For example, the Julian Date for 00:30:00.0 UT January 1, 2013, is 2,456,293.520833.[5] The Julian Period is a chronological interval of 7980 years beginning 4713 BC. It has been used by historians since its introduction in 1583 to convert between different calendars. 2015 is year 6728 of the current Julian Period. -

Precision and Splendor: Clocks and Watches at the Frick Collection

ON VIEW IN THE PORTICO GALLERY PRECISION AND SPLENDOR: CLOCKS AND WATCHES AT THE FRICK COLLECTION January 23, 2013, through March 9, 2014 (extended, note new end date) Today the question “What time is it?” is quickly answered by looking at any number of devices around us, from watches to phones to computers. For millennia, however, determining the correct time was not so simple. In fact, it was not until the late thirteenth century that the first mechanical clocks were made, slowly replacing sundials and water clocks. It would take several hundred years before mechanical timekeepers became reliable and accurate. This exhibition explores the discoveries and innovations made in the field of horology from the early sixteenth to the nineteenth century. The exhibition, to be shown in the new Portico Gallery, features eleven clocks and fourteen watches from the Winthrop Kellogg Edey bequest, along with five clocks lent Mantel Clock with Study and Philosophy, movement by Renacle-Nicolas Sotiau (1749−1791), figures after Simon-Louis by a private collector, works that have never before been seen in New York Boizot (1743–1809), c. 1785−90, patinated and gilt bronze, marble, enameled metal, and glass, H.: 22 inches, private collection City. Together, these objects chronicle the evolution over the centuries of more accurate and complex timekeepers and illustrate the aesthetic developments that reflected Europe’s latest styles. Precision and Splendor: Clocks and Watches at The Frick Collection was organized by Charlotte Vignon, Associate Curator of Decorative Arts, The Frick Collection. Major funding for the exhibition is provided by Breguet. Additional support is generously provided by The Selz Foundation, Peter and Gail Goltra, and the David Berg Foundation. -

Elapsed Time Worksheets for Grade 3 Pdf

Elapsed time worksheets for grade 3 pdf Continue Your student will follow Ann throughout the day, figuring out the past time of her activities. Want to help support the site and remove ads? Become a patron via patreon or donate via PayPal. Each of the printed PDF time sheets on this page includes a response key with time for each person's watch, as well as the actual time between the two values. These Telling Time sheets teach how to read facial clocks! One of the strangest mechanical devices around, of course, is analog watches. We see them everywhere because for so long they have been a pinacle of design and engineering. The miniaturization of analog watches down to the wristwatch remains today a stunning achievement, competing in many ways with the microchip in its expression of human ingenuity. Being able to say the time from analog watches remains a skill that will be relevant in the digital age, if for no other reason than the analog watch continues to represent a noble achievement whether it is on the citizen's watch or on the wrist. Talking time sheets to an hour and minutes Buying up the competence speaking time requires a lot of practice, and these sheets are here to help! Start with sheets that tell the time on the whole clock and then progress through variations that deal with 15-minute intervals. Finally, work on talking time up to minutes to become completely comfortable with reading any position on the face clock. The time tables here include versions that require reading the face of the clock, as well as drawing it accordingly, given the numerical time. -

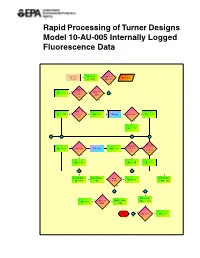

Rapid Processing of Turner Designs Model 10-AU-005 Internally Logged Fluorescence Data

Rapid Processing of Turner Designs Model 10-AU-005 Internally Logged Fluorescence Data Subroutine M1 D 0 MM D 2 Y - - - Read Year Timcnt M2 D 0 or Mont D 2? N MM D Y 1, 3, 5, 7, Y Mont ¤ ? M1 D 31 8, 10, or MM 12? N N ? MM D 4, YN T M1 D 30 6, 9, or - MM D 2 - Call Leap - Leap Year? - M1 D 29 11? F ? M1 D 28 ? - ? - ? - ? 6 ? Mont D Mont D T N N 1, 3, 5, 7, M D 29 Leap Year? Call Leap Mont D 2 4, 6, 9, or 2 8, 10, or 11? 12? F Y Y ? ? ? M2 D 28 M2 D 30 M2 D 31 - ? ? ? ? Days D Days + Mont D Mont Mont Y Days D Days - - - Mont D 1 M2 Day C1 > 12? CDD Day N ? - ? ? HN D 24 YNMont ¤ Days D Days . / Day D 0 - Days Nct MM? CDD ? NY Return HN < 0? - HN D 0 6 Cover Figure Flow chart for FLOWTHRU program subroutine TIMCNT explaining how FLOWTHRU handles severe time breaks in logged data files. EPA/600/R-04/071 July 2004 Rapid Processing of Turner Designs Model 10-AU-005 Internally Logged Fluorescence Data National Center for Environmental Assessment Office of Research and Development U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Washington, DC 20460 DISCLAIMER This document has been reviewed in accordance with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency policy and appro ved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ABSTRACT Continuous recording of dye fluorescence using field fluorometers at selected sampling sites facilitates acquisition of real-time dye tracing data. -

Flowtime: a Form of Decimal Time

8-1 1 Chapter Eight Flowtime: A form of decimal time Most people take our time system for granted. If someone asks “What time is it?” there usually isn’t a lot of controversy about what system of time is being used. Nearly everyone worldwide uses a common system of time based on 24 hours in a day, 60 minutes per hour, and 60 seconds per minute. The only relativity that enters the picture is that the time is different depending on the time zone. So when it’s 8:00 am in New York, for example, it’s 1:00 pm in London. The origins of our 24 hour clock go all the way back to the Egyptians and the Babylonians. The Egyptians divided the time from sunrise to sunset into ten hours of daylight. They also had two hours of twilight and twelve hours of night. This system goes back as far as 1300 B.C. The total is 24 hours per day, which we still have in our time-keeping systems today. The origin of our minute and second goes back to the Babylonians. The Babylonians did their astronomical calculations in a base 60 system. The first fractional place in this base 60 system we now call a minute. The second fractional place in this system we now call a second. It is amazing that, after 3300 years, we are still operating on a system of time that was invented long before technology, and 2600 years before the invention of mechanical clocks (around 1300). Today we have many reasons to divide time into smaller and smaller units.