Overview Orientation of the Night Sky Figure 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Photochemically Driven Collapse of Titan's Atmosphere

REPORTS has escaped, the surface temperature again Photochemically Driven Collapse decreases, down to about 86 K, slightly of Titan’s Atmosphere above the equilibrium temperature, because of the slight greenhouse effect resulting Ralph D. Lorenz,* Christopher P. McKay, Jonathan I. Lunine from the N2 opacity below (longward of) 200 cm21. Saturn’s giant moon Titan has a thick (1.5 bar) nitrogen atmosphere, which has a These calculations assume the present temperature structure that is controlled by the absorption of solar and thermal radiation solar constant of 15.6 W m22 and a surface by methane, hydrogen, and organic aerosols into which methane is irreversibly converted albedo of 0.2 and ignore the effects of N2 by photolysis. Previous studies of Titan’s climate evolution have been done with the condensation. As noted in earlier studies assumption that the methane abundance was maintained against photolytic depletion (5), when the atmosphere cools during the throughout Titan’s history, either by continuous supply from the interior or by buffering CH4 depletion, the model temperature at by a surface or near surface reservoir. Radiative-convective and radiative-saturated some altitudes in the atmosphere (here, at equilibrium models of Titan’s atmosphere show that methane depletion may have al- ;10 km for 20% CH4 surface humidity) lowed Titan’s atmosphere to cool so that nitrogen, its main constituent, condenses onto becomes lower than the saturation temper- the surface, collapsing Titan into a Triton-like frozen state with a thin atmosphere. -

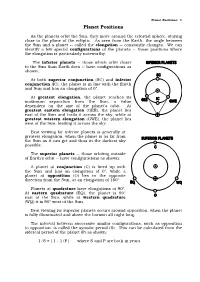

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur

Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur To cite this version: Alex Soumbatov-Gur. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution. [Research Report] Karpov institute of physical chemistry. 2019. hal-02147461 HAL Id: hal-02147461 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02147461 Submitted on 4 Jun 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Phobos, Deimos: Formation and Evolution Alex Soumbatov-Gur The moons are confirmed to be ejected parts of Mars’ crust. After explosive throwing out as cone-like rocks they plastically evolved with density decays and materials transformations. Their expansion evolutions were accompanied by global ruptures and small scale rock ejections with concurrent crater formations. The scenario reconciles orbital and physical parameters of the moons. It coherently explains dozens of their properties including spectra, appearances, size differences, crater locations, fracture symmetries, orbits, evolution trends, geologic activity, Phobos’ grooves, mechanism of their origin, etc. The ejective approach is also discussed in the context of observational data on near-Earth asteroids, main belt asteroids Steins, Vesta, and Mars. The approach incorporates known fission mechanism of formation of miniature asteroids, logically accounts for its outliers, and naturally explains formations of small celestial bodies of various sizes. -

Basic Principles of Celestial Navigation James A

Basic principles of celestial navigation James A. Van Allena) Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 52242 ͑Received 16 January 2004; accepted 10 June 2004͒ Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s geographic position by the observation of identified stars, identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. This subject has a multitude of refinements which, although valuable to a professional navigator, tend to obscure the basic principles. I describe these principles, give an analytical solution of the classical two-star-sight problem without any dependence on prior knowledge of position, and include several examples. Some approximations and simplifications are made in the interest of clarity. © 2004 American Association of Physics Teachers. ͓DOI: 10.1119/1.1778391͔ I. INTRODUCTION longitude ⌳ is between 0° and 360°, although often it is convenient to take the longitude westward of the prime me- Celestial navigation is a technique for determining one’s ridian to be between 0° and Ϫ180°. The longitude of P also geographic position by the observation of identified stars, can be specified by the plane angle in the equatorial plane identified planets, the Sun, and the Moon. Its basic principles whose vertex is at O with one radial line through the point at are a combination of rudimentary astronomical knowledge 1–3 which the meridian through P intersects the equatorial plane and spherical trigonometry. and the other radial line through the point G at which the Anyone who has been on a ship that is remote from any prime meridian intersects the equatorial plane ͑see Fig. -

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number. -

Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock

Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock Entering Information in the Electronic Time Clock (ETC) for Assistance Provided to Other Routes WHEN PROVIDING OFFICE ASSISTANCE Press "MOVE" Press "OFFICE" Type in the number of the route that your are assisting. This will be a six digit number that begins with 0 followed by the last two numbers of the zip code for that route and then one or two zeros and the number of the route. Example for route 2 in the 20886 zip code would be 086002 Route 15 in the 20878 zip code would be 078015 Then swipe your badge WHEN YOU HAVE FINISHED PROVIDING OFFICE ASSISTANCE Press "MOVE" Press "OFFICE" Type in the number of the route you are assigned to that day (as above) Swipe your badge WHEN PROVIDING STREET ASSISTANCE AND ENTERING THE INFORMATION WHEN YOU RETURN FROM THE STREET Press "MOVE" Press "STREET" Type in the number of the route that you assisted (as above) Type in the time that you started to provide assistance in decimal hours (3:30 would be 1550). See the conversion chart. Swipe your badge Press "MOVE" Press "STREET" Type in YOUR route number (as above) Type in the time you finished providing assistance to the other route, Swipe your badge Page 1 TIME CONVERSION TABLE Postal timekeepers use a combination of military time (for the hours) and decimal time (for the minutes). Hours in the morning need no conversion, but use a zero before hours below 10; to show evening hours, add 12. (Examples: 6:00 am = 0600; 1:00 pm = 1300.) Using this chart, convert minutes to fractions of one hundred. -

Light, Color, and Atmospheric Optics

Light, Color, and Atmospheric Optics GEOL 1350: Introduction To Meteorology 1 2 • During the scattering process, no energy is gained or lost, and therefore, no temperature changes occur. • Scattering depends on the size of objects, in particular on the ratio of object’s diameter vs wavelength: 1. Rayleigh scattering (D/ < 0.03) 2. Mie scattering (0.03 ≤ D/ < 32) 3. Geometric scattering (D/ ≥ 32) 3 4 • Gas scattering: redirection of radiation by a gas molecule without a net transfer of energy of the molecules • Rayleigh scattering: absorption extinction 4 coefficient s depends on 1/ . • Molecules scatter short (blue) wavelengths preferentially over long (red) wavelengths. • The longer pathway of light through the atmosphere the more shorter wavelengths are scattered. 5 • As sunlight enters the atmosphere, the shorter visible wavelengths of violet, blue and green are scattered more by atmospheric gases than are the longer wavelengths of yellow, orange, and especially red. • The scattered waves of violet, blue, and green strike the eye from all directions. • Because our eyes are more sensitive to blue light, these waves, viewed together, produce the sensation of blue coming from all around us. 6 • Rayleigh Scattering • The selective scattering of blue light by air molecules and very small particles can make distant mountains appear blue. The blue ridge mountains in Virginia. 7 • When small particles, such as fine dust and salt, become suspended in the atmosphere, the color of the sky begins to change from blue to milky white. • These particles are large enough to scatter all wavelengths of visible light fairly evenly in all directions. -

Solar Engineering Basics

Solar Energy Fundamentals Course No: M04-018 Credit: 4 PDH Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] Solar Energy Fundamentals Harlan H. Bengtson, PhD, P.E. COURSE CONTENT 1. Introduction Solar energy travels from the sun to the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation. In this course properties of electromagnetic radiation will be discussed and basic calculations for electromagnetic radiation will be described. Several solar position parameters will be discussed along with means of calculating values for them. The major methods by which solar radiation is converted into other useable forms of energy will be discussed briefly. Extraterrestrial solar radiation (that striking the earth’s outer atmosphere) will be discussed and means of estimating its value at a given location and time will be presented. Finally there will be a presentation of how to obtain values for the average monthly rate of solar radiation striking the surface of a typical solar collector, at a specified location in the United States for a given month. Numerous examples are included to illustrate the calculations and data retrieval methods presented. Image Credit: NOAA, Earth System Research Laboratory 1 • Be able to calculate wavelength if given frequency for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Be able to calculate frequency if given wavelength for specified electromagnetic radiation. • Know the meaning of absorbance, reflectance and transmittance as applied to a surface receiving electromagnetic radiation and be able to make calculations with those parameters. • Be able to obtain or calculate values for solar declination, solar hour angle, solar altitude angle, sunrise angle, and sunset angle. -

Project Horizon Report

Volume I · SUMMARY AND SUPPORTING CONSIDERATIONS UNITED STATES · ARMY CRD/I ( S) Proposal t c• Establish a Lunar Outpost (C) Chief of Ordnance ·cRD 20 Mar 1 95 9 1. (U) Reference letter to Chief of Ordnance from Chief of Research and Devel opment, subject as above. 2. (C) Subsequent t o approval by t he Chief of Staff of reference, repre sentatives of the Army Ballistic ~tissiles Agency indicat e d that supplementar y guidance would· be r equired concerning the scope of the preliminary investigation s pecified in the reference. In particular these r epresentatives requested guidance concerning the source of funds required to conduct the investigation. 3. (S) I envision expeditious development o! the proposal to establish a lunar outpost to be of critical innportance t o the p. S . Army of the future. This eva luation i s appar ently shar ed by the Chief of Staff in view of his expeditious a pproval and enthusiastic endorsement of initiation of the study. Therefore, the detail to be covered by the investigation and the subs equent plan should be as com plete a s is feas ible in the tin1e limits a llowed and within the funds currently a vailable within t he office of t he Chief of Ordnance. I n this time of limited budget , additional monies are unavailable. Current. programs have been scrutinized r igidly and identifiable "fat'' trimmed awa y. Thus high study costs are prohibitive at this time , 4. (C) I leave it to your discretion t o determine the source and the amount of money to be devoted to this purpose. -

Alasdair Gray and the Postmodern

ALASDAIR GRAY AND THE POSTMODERN Neil James Rhind PhD in English Literature The University Of Edinburgh 2008 2 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis has been composed by me; that it is entirely my own work, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified on the title page. Signed: Neil James Rhind 3 CONTENTS Title……………………………………….…………………………………………..1 Declaration……………………………….…………………………………………...2 Contents………………………………………………………………………………3 Abstract………………………………….………………………………..…………..4 Note on Abbreviations…………………………………………………………….….6 1. Alasdair Gray : Sick of Being A Postmodernist……………………………..…….7 2. The Generic Blending of Lanark and the Birth of Postmodern Glasgow…….…..60 3. RHETORIC RULES, OK? : 1982, Janine and selected shorter novels………….122 4. Reforming The Victorians: Poor Things and Postmodern History………………170 5. After Postmodernism? : A History Maker………………………………………….239 6. Conclusion: Reading Postmodernism in Gray…………………………………....303 Endnotes……………………………………………………………………………..320 Works Cited………………………………………………………………………….324 4 ABSTRACT The prominence of the term ‘Postmodernism’ in critical responses to the work of Alasdair Gray has often appeared at odds with Gray’s own writing, both in his commitment to seemingly non-postmodernist concerns and his own repeatedly stated rejection of the label. In order to better understand Gray’s relationship to postmodernism, this thesis begins by outlining Gray’s reservations in this regard. Principally, this is taken as the result of his concerns -

Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael

an Educator’s Guid E INSIDE • Links to Education Standards • Introduction to Exoplanets • Glossary of Terms • Classroom Activities Table of Contents Photo © Michael Malyszko Photo © Michael For The TeaCher About This Guide .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Connections to Education Standards ................................................................................................... 5 Show Synopsis .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Meet the “Stars” of the Show .................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction to Exoplanets: The Basics .................................................................................................. 9 Delving Deeper: Teaching with the Show ................................................................................................13 Glossary of Terms ..........................................................................................................................................24 Online Learning Tools ..................................................................................................................................26 Exoplanets in the News ..............................................................................................................................27 During -

5 the Orbit of Mercury

Name: Date: 5 The Orbit of Mercury Of the five planets known since ancient times (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn), Mercury is the most difficult to see. In fact, of the 6 billion people on the planet Earth it is likely that fewer than 1,000,000 (0.0002%) have knowingly seen the planet Mercury. The reason for this is that Mercury orbits very close to the Sun, about one third of the Earth’s average distance. Therefore it is always located very near the Sun, and can only be seen for short intervals soon after sunset, or just before sunrise. It is a testament to how carefully the ancient peoples watched the sky that Mercury was known at least as far back as 3,000 BC. In Roman mythology Mercury was a son of Jupiter, and was the god of trade and commerce. He was also the messenger of the gods, being “fleet of foot”, and commonly depicted as having winged sandals. Why this god was associated with the planet Mercury is obvious: Mercury moves very quickly in its orbit around the Sun, and is only visible for a very short time during each orbit. In fact, Mercury has the shortest orbital period (“year”) of any of the planets. You will determine Mercury’s orbital period in this lab. [Note: it is very helpful for this lab exercise to review Lab #1, section 1.5.] Goals: to learn about planetary orbits • Materials: a protractor, a straight edge, a pencil and calculator • Mercury and Venus are called “inferior” planets because their orbits are interior to that of the Earth.