Applying Existential Social Psychology to Mental Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

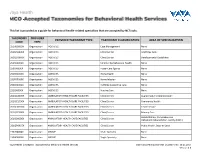

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders NDSCS Counseling Services hopes the following information will help you gain a better understanding of eating disorders. If you believe you or someone you know is experiencing related concerns and would like to visit with a counselor, please call NDSCS Counseling Services for an appointment - 701.671.2286. Definition There is a commonly held view that eating disorders are a lifestyle choice. Eating disorders are actually serious and often fatal illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Signs and Symptoms Anorexia nervosa People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, and eat very small quantities of only certain foods. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. While many young women and men with this disorder die from complications associated with starvation, others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders. Symptoms include: • Extremely restricted eating • Extreme thinness (emaciation) • A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight • Intense fear of gaining weight • Distorted body image, a self-esteem -

Understanding Mental Health

UNDERSTANDING MENTAL HEALTH WHAT IS MENTAL HEALTH? Our mental health directly influences how we think, feel and act: it also affects our physical health. Work, in fact, is actually one of the best things for protecting our mental health, but it can also adversely affect it. Good mental health and well-being is not an on-off A person’s mental health moves back and forth along this range during experience. We can all have days, weeks or months their lifetime, in response to different stressors and circumstances. At where we feel resilient, strong and optimistic, the green end of the continuum, people are well; showing resilience regardless of events or situations. Often that can and high levels of wellbeing. Moving into the yellow area, people be mixed with or shift to a very different set of may start to have difficulty coping. In the orange area, people have thoughts, feelings and behaviours; or not feeling more difficulty coping and symptoms may increase in severity and resilient and optimistic in just one or two areas of frequency. At the red end of the continuum, people are likely to be our life. For about twenty-five per cent of us, that experiencing severe symptoms and may be at risk of self-harm or may shift to having a significant impact on how suicide. we think, feel and act in many parts of our lives, including relationships, experiences at work, sense of connection to peer groups and our personal sense of worth, physical health and motivation. This could lead to us developing a mental health condition such as anxiety, depression, substance misuse. -

PSY 324: Social Psychology of Emotion

Advanced Social Psychology: Emotion PSY 324 Section A Spring 2008 Instructor: Christina M. Brown, M.A., A.B.D. CRN: 66773 E-mail: [email protected] Class Time: Monday, Wednesday, Friday Office Hours: 336 Psych MW 2:00-3:00 or by appt 1:00 - 1:50 pm Office Phone: (513) 529-1755 Location: 127 PSYC Required Readings Niedenthal, P. M., Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2006). Psychology of emotion: Interpersonal, experiential, and cognitive approaches. New York: Taylor & Francis. *The textbook is $35 Amazon.com and can be found on Half.com for as cheap as $26. Journal articles will be assigned regularly throughout the semester. These will be available as downloadable .pdf files on Blackboard. Course Description This course is on the advanced social psychology of emotion. Students will gain an understanding of the function of emotion, structure of emotion, and the interplay between emotion, cognition, behavior, and physiology. We will spend most of our time discussing theories of emotion and empirical evidence supporting and refuting these theories. Research is the foundation of psychology, and so a considerable amount of time will be spent reading, discussing, and analyzing research. There will be regular discussions that will each focus on a single assigned reading (always a journal article, which will be made available on Blackboard), and it is my hope that these discussions are active, thoughtful, and generative (meaning that students leave the discussion with research questions and ideas for future research). Although there will be some days entirely devoted to discussion, I hope that we can weave discussion into lecture-based days as well. -

Social Psychology Glossary

Social Psychology Glossary This glossary defines many of the key terms used in class lectures and assigned readings. A Altruism—A motive to increase another's welfare without conscious regard for one's own self-interest. Availability Heuristic—A cognitive rule, or mental shortcut, in which we judge how likely something is by how easy it is to think of cases. Attractiveness—Having qualities that appeal to an audience. An appealing communicator (often someone similar to the audience) is most persuasive on matters of subjective preference. Attribution Theory—A theory about how people explain the causes of behavior—for example, by attributing it either to "internal" dispositions (e.g., enduring traits, motives, values, and attitudes) or to "external" situations. Automatic Processing—"Implicit" thinking that tends to be effortless, habitual, and done without awareness. B Behavioral Confirmation—A type of self-fulfilling prophecy in which people's social expectations lead them to behave in ways that cause others to confirm their expectations. Belief Perseverance—Persistence of a belief even when the original basis for it has been discredited. Bystander Effect—The tendency for people to be less likely to help someone in need when other people are present than when they are the only person there. Also known as bystander inhibition. C Catharsis—Emotional release. The catharsis theory of aggression is that people's aggressive drive is reduced when they "release" aggressive energy, either by acting aggressively or by fantasizing about aggression. Central Route to Persuasion—Occurs when people are convinced on the basis of facts, statistics, logic, and other types of evidence that support a particular position. -

Redalyc. Social Psychology of Mental Health: the Social Structure and Personality Prespective

Scientific Information System Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Esteban Sánchez Moreno, Ana Barrón López de Roda Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Prespective The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol. 6, núm. 1, mayo, 2003 Universidad Complutense de Madrid España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17260102 The Spanish Journal of Psychology, ISSN (Printed Version): 1138-7416 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España How to cite Complete issue More information about this article Journal's homepage www.redalyc.org Non-Profit Academic Project, developed under the Open Acces Initiative The Spanish Journal of Psychology Copyright 2003 by The Spanish Journal of Psychology 2003, Vol. 6, No. 1, 3-11 1138-7416 Social Psychology of Mental Health: The Social Structure and Personality Perspective Esteban Sánchez Moreno and Ana Barrón López de Roda Complutense University of Madrid Previous research has revealed a persistent association between social structure and mental health. However, most researchers have focused only on the psychological and psychosocial aspects of that relationship. The present paper indicates the need to include the social and structural bases of distress in our theoretical models. Starting from a general social and psychological model, our research considered the role of several social, environmental, and structural variables (social position, social stressors, and social integration), psychological factors (self-esteem), and psychosocial variables (perceived social support). The theoretical model was tested working with a group of Spanish participants (N = 401) that covered a range of social positions. The results obtained using structural equation modeling support our model, showing the relevant role played by psychosocial, psychological and social, and structural factors. -

Early Identification of Psychosis a Primer

Early Identification of Psychosis A Primer Mental Health Evaluation & Community Consultation Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction...............................................................................................................3 Psychosis and Early Intervention........................................................................4 Why is Early Intervention Needed?...................................................................5 Risk and Onset..........................................................................................................6 Course of First-Episode Psychosis 1. Prodrome........................................................................................................7 2. Acute Phase....................................................................................................8 3. Recovery Phase..............................................................................................9 Summary of First-Episode Psychosis...............................................................11 Tips for Helpers......................................................................................................12 More Resources......................................................................................................15 Acknowledgements...............................................................................................16 2 INTRODUCTION Psychosis is a condition characterized by loss of contact with reality and may involve severe disturbances in perception, cognition, behavior, -

Illusion and Well-Being: a Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health

Psyehologlcal Bulletin Copyright 1988 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 1988, Vol. 103, No. 2, 193-210 0033-2909/88/$00.75 Illusion and Well-Being: A Social Psychological Perspective on Mental Health Shelley E. Taylor Jonathon D. Brown University of California, Los Angeles Southern Methodist University Many prominenttheorists have argued that accurate perceptions of the self, the world, and the future are essential for mental health. Yet considerable research evidence suggests that overly positive self- evaluations, exaggerated perceptions of control or mastery, and unrealistic optimism are characteris- tic of normal human thought. Moreover, these illusions appear to promote other criteria of mental health, including the ability to care about others, the ability to be happy or contented, and the ability to engage in productive and creative work. These strategies may succeed, in large part, because both the social world and cognitive-processingmechanisms impose filters on incoming information that distort it in a positive direction; negativeinformation may be isolated and represented in as unthreat- ening a manner as possible. These positive illusions may be especially useful when an individual receives negative feedback or is otherwise threatened and may be especially adaptive under these circumstances. Decades of psychological wisdom have established contact dox: How can positive misperceptions of one's self and the envi- with reality as a hallmark of mental health. In this view, the ronment be adaptive when accurate information processing wcU-adjusted person is thought to engage in accurate reality seems to be essential for learning and successful functioning in testing,whereas the individual whose vision is clouded by illu- the world? Our primary goal is to weave a theoretical context sion is regarded as vulnerable to, ifnot already a victim of, men- for thinking about mental health.