Understanding a First Episode of Psychosis-Caregiver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Redlands Psychiatrist Referral List Most Major Insurances Accepted Including Medi-Medi and Other Government (909) 335-3026 Insurances

University of Redlands Psychiatrist Referral List Most major insurances accepted including medi-medi and other government (909) 335-3026 insurances. But not limited to Aetna HMO/PPO, Cigna, TRIWEST, MANAGED Inland Psychiatric Medical Group 1809 W. Redlands Blvd. HEALTH NETWORK, Universal care (only for brand new day), Blue Shield, IEHP, http://www.inlandpsych.com/ Redlands, CA 92373 PPO / Most HMO, MEDICARE, Blue Cross Blue Shield, KAISER (with referral), BLUE CROSS / ANTHEM, HeathNet Providers available at this SPECIALTIES location: Chatsuthiphan, Visit MD Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Borderline Personality Disorders, Depression, Medication Management, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd Belen, Nenita MD Adhd/Add, Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Depression, Medication Management, Meet And Greet, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd, Panic Disorders, Phobias, Ptsd Adhd/Add, Adoption Issues, Aids/Hiv, Anger Management, Anxiety Disorder, Bipolar Disorders, Borderline Personality Disorders, Desai, David MD Conduct/Disruptive Disorder, Depression, Dissociative Disorder, Medication Management Farooqi, Mubashir MD Addictionology (md Only), Adhd/Add, Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-evening, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Conduct/Disruptive Disorder, Depression, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd, Ptsd Julie Wareham, MD General Psychiatry, Inpatient hospital coverage for adolescent, adult, chemical dependency and consult and liaison services. Sigrid Formantes, MD General Psychiatry, General Psychiatrist Neelima Kunam, MD General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist John Kohut, MD General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist Anthony Duk, MD InlandPsych Redlands, Inc. (909)798-1763 http://www.inlandpsychredlands.com 255 Terracina Blvd. St. 204, Most major health insurance plans accepted, including student insurance Redlands, CA 92373 Providers available at this SPECIALTIES location: * Paladugu, Geetha K. MD Has clinical experience in both inpatient and outpatient settings. -

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

“Cat-Gras” Delusion: a Unique Misidentification Syndrome and a Novel Explanation

Neurocase The Neural Basis of Cognition ISSN: 1355-4794 (Print) 1465-3656 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/nncs20 “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation R. Ryan Darby & David Caplan To cite this article: R. Ryan Darby & David Caplan (2016) “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation, Neurocase, 22:2, 251-256, DOI: 10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 Published online: 14 Jan 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1195 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 4 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=nncs20 Download by: [Vanderbilt University Library] Date: 06 December 2017, At: 06:39 NEUROCASE, 2016 VOL. 22, NO. 2, 251–256 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2015.1136335 “Cat-gras” delusion: a unique misidentification syndrome and a novel explanation R. Ryan Darbya,b,c and David Caplana,c aDepartment of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; bDepartment of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA; cHarvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA ABSRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Capgras syndrome is a distressing delusion found in a variety of neurological and psychiatric diseases Received 23 June 2015 where a patient believes that a family member, friend, or loved one has been replaced by an imposter. Accepted 20 December 2015 Patients recognize the physical resemblance of a familiar acquaintance but feel that the identity of that KEYWORDS person is no longer the same. -

Paranoia and Slowed Cognition Ijeoma Ijeaku, MD, MPH, and Melissa Pereau, MD

Cases That Test Your Skills Paranoia and slowed cognition Ijeoma Ijeaku, MD, MPH, and Melissa Pereau, MD Mr. K, age 45, is paranoid, combative, and agitated. Two weeks How would you ago he sustained chemical abrasions at home. What could be handle this case? Visit CurrentPsychiatry.com causing his altered mental status? to input your answers and see how your colleagues responded CASE Behavioral changes aggressive and combative. He throws chairs at Mr. K, age 45, is brought to the emergency de- his peers and staff on the unit and is placed in partment (ED) by his wife for severe paranoia, physical restraints. He requires several doses combative behavior, confusion, and slowed of IM haloperidol, 5 mg, lorazepam, 2 mg, and cognition. Mr. K tells the ED staff that a chemi- diphenhydramine, 50 mg, for severe agitation. cal abrasion he sustained a few weeks earlier Mr. K is guarded, perseverative, and selectively has spread to his penis, and insists that his mute. He avoids eye contact and has poor penis is retracting into his body. He has tied grooming. He has slow thought processing and a string around his penis to keep it from dis- displays concrete thought process. Prednisone appearing into his body. According to Mr. K’s is discontinued and olanzapine, titrated to 30 wife, he went to an urgent care clinic 2 weeks mg/d, and mirtazapine, titrated to 30 mg/d, are ago after he sustained chemical abrasions started for psychosis and depression. from exposure to cleaning solution at home. Mr. K’s mood and behavior eventually re- The provider at the urgent care clinic started turn to baseline but slowed cognition persists. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Two Cases of Intractable Auditory Hallucination Successfully Treated with Sound Therapy

ORIGINAL ARTICLE International Tinnitus Journal. 2010;16(1):29-31. Two cases of intractable auditory hallucination successfully treated with sound therapy Yutaka Kaneko, M.D. 1 Yasuhiko Oda, M.D. 2 Fumiyuki Goto, M.D. 3 Abstract We report two cases of patients with schizoaffective disorder with treatment-refractory auditory verbal hallucinations (AVHs) who were successfully treated with sound therapy, which is effective to treat tinnitus. AVHs in both patients were alleviated within about one month, and no recurrence was reported for 31 and 17 months after the sound the- rapy together with medication. Further studies may confirm the therapeutic value of sound therapy in patients with intractable AVHs. Keywords: auditory hallucinations, sound therapy. 1 Kaneko Otorhinolaryngology Clinic, Sendai, Miyagi, 2 Kunimidai Hospital (Psychiatry), Sendai, Miyagi, and 3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Hino Municipal Hospital, Tokyo, Japan Corresponding Author: Yutaka Kaneko, M.D. Kaneko Otorhinolaryngology Clinic 2-9-14 Kunimi,Aoba-ku,Sendai 981-0943,Japan Tel & Fax: +81-22-233-7722 E-mail: [email protected] International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 16, No 1 (2010) www.tinnitusjournal.com 29 INTRODUCTION levomepromazine and olanzapine, together with fluvo- xamine maleate and sodium valproate during her hos- Auditory hallucinations (AHs) are generally defined pitalization for 3 years. She then received a psychiatric as false perceptions manifesting as “voices commenting” referral to our ear clinic for audiological evaluation and or “voices conversing” in patients with schizophrenia and treatment in August 2006. Her hearing level, calculated schizoaffective disorder. Auditory verbal hallucinations as the average across the frequencies 250, 500, 1000, (AVHs) are one of the major symptoms for the diagnosis and 2000 Hz, was 13.8 dB in the right ear and 18.8 dB of these disorders as well as the evaluation of psychotic in the left ear. -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Summary of Junior MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients Under 18 with Anorexia Nervosa

CR168s Summary of Junior MARSIPAN: Management of Really Sick Patients under 18 with Anorexia Nervosa COLLEGE REPORT College Report 168s October 2015 Approved by: Policy and Public Affairs Committee (PPAC), November 2014 Due for revision: 2016 © 2015 The Royal College of Psychiatrists College Reports constitute College policy. They have been sanctioned by the College via the Policy and Public Affairs Committee (PPAC). For full details of reports available and how to obtain them, visit the College website at http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/publications/ collegereports.aspx The Royal College of Psychiatrists is a charity registered in England and Wales (228636) and in Scotland (SC038369). Contents Authors 2 Key recommendations 3 Risk assessment: how ill is the patient? 4 Location of care 9 Management in specific healthcare settings 11 Management in specialist eating disorders beds 18 Audit and review 20 Resources and further guidance 21 References 22 Contents 1 Authors The authors of this report are multidisciplinary, Dr Jane Whittaker, Consultant Child and independent, and have no conflicts of interest to Adolescent Psychiatrist, Manchester Children’s declare relating to the report. Hospital, Manchester Dr Agnes Ayton, Consultant Psychiatrist, Dr Damian Wood, Consultant Paediatrician, Cotswold House, Oxford Chair of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health’s Young People’s Health Special Dr Rob Barnett, General Practitioner, Liverpool Interest Group, Nottingham University Hospital, Dr Mark Beattie, Consultant Paediatric Nottingham Gastroenterologist, -

Specificity of Psychosis, Mania and Major Depression in A

Molecular Psychiatry (2014) 19, 209–213 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/14 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Specificity of psychosis, mania and major depression in a contemporary family study CL Vandeleur1, KR Merikangas2, M-PF Strippoli1, E Castelao1 and M Preisig1 There has been increasing attention to the subgroups of mood disorders and their boundaries with other mental disorders, particularly psychoses. The goals of the present paper were (1) to assess the familial aggregation and co-aggregation patterns of the full spectrum of mood disorders (that is, bipolar, schizoaffective (SAF), major depression) based on contemporary diagnostic criteria; and (2) to evaluate the familial specificity of the major subgroups of mood disorders, including psychotic, manic and major depressive episodes (MDEs). The sample included 293 patients with a lifetime diagnosis of SAF disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), 110 orthopedic controls, and 1734 adult first-degree relatives. The diagnostic assignment was based on all available information, including direct diagnostic interviews, family history reports and medical records. Our findings revealed specificity of the familial aggregation of psychosis (odds ratio (OR) ¼ 2.9, confidence interval (CI): 1.1–7.7), mania (OR ¼ 6.4, CI: 2.2–18.7) and MDEs (OR ¼ 2.0, CI: 1.5–2.7) but not hypomania (OR ¼ 1.3, CI: 0.5–3.6). There was no evidence for cross-transmission of mania and MDEs (OR ¼ .7, CI:.5–1.1), psychosis and mania (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.4–2.7) or psychosis and MDEs (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.7–1.4). -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

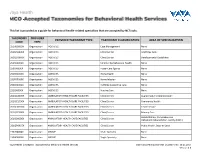

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

The Trauma of First Episode Psychosis: the Role of Cognitive Mediation

The trauma of first episode psychosis: the role of cognitive mediation Chris Jackson, Claire Knott, Amanda Skeate, Max Birchwood Objective: First episode psychosis can be a distressing and traumatic event which has been linked to comorbid symptomatology, including anxiety, depression and PTSD symp- toms (intrusions, avoidance, etc.). However, the link between events surrounding a first episode psychosis (i.e. police involve- ment, admission, use of Mental Health Act, etc.) and PTSD symptoms remains unproven. In the PTSD literature, attention has now turned to the patient’s appraisal of the traumatic event as a key mediator. In this study we aim to evaluate the diagnostic status of first episode psychosis as a PTSD-triggering event and to determine the extent to which cognitive factors such as appraisals and coping mechanisms can mediate the expression of PTSD (traumatic) symptomatology. Method: Approximately 1.5 years after their first episode of psychosis, patients were assessed for traumatic symptoms, conformity to DSM-IV criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and their appraisals of the traumatic events and coping strategies. Psychotic symptomatology was also measured. Results: 31% of the sample of 35 patients who agreed to participate reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD. Although no relationship was found between PTSD (traumatic) symptoms and potentially traumatic aspects of the first episode (including place of treatment, detention under the MHA etc.), intrusions and avoidance were positively related to retrospective appraisals of stressfulness of the ward (i.e. the more stressful they rated it the greater the number of PTSD symptoms) and the patient’s coping style (sealers were less likely to report intrusive re-experiencing but more likely to report avoidance).