Major Events and Policy Issues in E.C. Competition Law, 1999-Part 1: [Zoo01 I.C.C.L.R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 PRESSEMAPPE Nyon, Schweiz Sonntag, 18

AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 PRESSEMAPPE Nyon, Schweiz Sonntag, 18. Oktober 2015 11.20MEZ Letzte Aktualisierung 16/10/2015 18:07MEZ OFFIZIELLE SPONSOREN DER UEFA EURO 2016 Fakten und Zahlen 2 Töpfe 3 Teamprofile: Topf 1 4 Teamprofile: Topf 2 25 Qualifikation zur UEFA EURO 2016 46 UEFA EURO Play-off-Geschichte 57 Legende 58 1 - AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 Sonntag 18 Oktober 2015 - 11.20CET (11.20 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Nyon, Schweiz Fakten und Zahlen 2 - AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 Sonntag 18 Oktober 2015 - 11.20CET (11.20 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Nyon, Schweiz Töpfe TOPF 1 TOPF 2 Bosnien und Dänemark Herzegowina Republik Irland Ukraine Norwegen Schweden Slowenien Ungarn 3 - AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 Sonntag 18 Oktober 2015 - 11.20CET (11.20 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Nyon, Schweiz Teamprofile: Topf 1 Bosnien und Herzegowina Ukraine Schweden 4 - AUSLOSUNG DER PLAY-OFFS FÜR DIE UEFA EURO 2016 Sonntag 18 Oktober 2015 - 11.20CET (11.20 Ortszeit) Pressemappe Nyon, Schweiz Bosnien und Herzegowina Bosnien und Herzegowina - Teamprofil Bestes Abschneiden bei einer EURO: Noch nie qualifiziert Trainer: Mehmed Baždarević Beste Torschützen: insgesamt - Edin Džeko (44); aktuell – Edin Džeko (44) Meiste Einsätze: insgesamt - Emir Spahić (85); aktuell - Emir Spahić (85) Gründung des Verbandes: 1992 Spitzname: Zmaveji (Drachen), Ljiljani (Lilien) Spielorte: Bilino Polje, Zenica; Asim Ferhatović, Sarajevo Zweimal scheiterte Bosnien und Herzegowina in den Play-offs zu einem großen Turnier (FIFA-WM 2010 und UEFA EURO 2012) zuletzt an Portugal, doch vor der WM 2014 klappte es endlich. Angeführt vom Torjägerduo Edin Džeko und Vedad Ibišević gewann das Team seine Qualifikationsgruppe und sicherte sich das Ticket für Brasilien. -

Uefa Euro 2020 Final Tournament Draw Press Kit

UEFA EURO 2020 FINAL TOURNAMENT DRAW PRESS KIT Romexpo, Bucharest, Romania Saturday 30 November 2019 | 19:00 local (18:00 CET) #EURO2020 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit 1 CONTENTS HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK ................................................ 3 - 9 HOW TO FOLLOW THE DRAW ................................................ 10 EURO 2020 AMBASSADORS .................................................. 11 - 17 EURO 2020 CITIES AND VENUES .......................................... 18 - 26 MATCH SCHEDULE ................................................................. 27 TEAM PROFILES ..................................................................... 28 - 107 POT 1 POT 2 POT 3 POT 4 BELGIUM FRANCE PORTUGAL WALES ITALY POLAND TURKEY FINLAND ENGLAND SWITZERLAND DENMARK GERMANY CROATIA AUSTRIA SPAIN NETHERLANDS SWEDEN UKRAINE RUSSIA CZECH REPUBLIC EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS 2018-20 - PLAY-OFFS ................... 108 EURO 2020 QUALIFYING RESULTS ....................................... 109 - 128 UEFA EURO 2016 RESULTS ................................................... 129 - 135 ALL UEFA EURO FINALS ........................................................ 136 - 142 2 UEFA EURO 2020 Final Tournament Draw | Press Kit HOW THE DRAW WILL WORK How will the draw work? The draw will involve the two-top finishers in the ten qualifying groups (completed in November) and the eventual four play-off winners (decided in March 2020, and identified as play-off winners 1 to 4 for the purposes of the draw). The draw will spilt the 24 qualifiers -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Personal Name: André van Meerkerk Address: Martinus Nijhofaan 101 Post Code: 4481 DH City: Kloetinge Country: Netherlands Phone number mobile: +31 6 53342654 Email: [email protected] Date of birth: 17 march 1962 Occupation: Multi-camera Director Company: André van Meerkerk Sport & Media Producties BV Website: www.andrevanmeerkerk.nl LinkedIn profile www.linkedin.com/in/andrevanmeerkerk Pure passion, many years (since 1987) of production and directing experience and a daily shot of adrenaline – nothing more, nothing less. And it works. These are the ingredients behind my successful productions for NOS, FOX Sports, Canal+, RTL, SBS6, Talpa, Ziggo and many other broadcasters. Look further to find out more about my production and directing experience in Sports. Productions This is my daily fare. Every year I take care of the production and direction of over 100 live television sport programmes. These programmes include many sports events, such as the matches in the Dutch Football Leaque, the Dutch National Football Team, the most important baseball tournaments and live coverage of boxing galas and other competitions. Besides this sports-based work, I also take care of the training of new directors. Television programmes I am specialised in live programmes that makes every fibre in your body feel the excitement and tension. It is necessary to react quickly, maintain an overview and to be able to draw on knowledge of the game. And it is always a matter of close collaboration with a strong and experienced crew. Directing It all starts with passion - but that on itself is not enough… Being a good director means understanding how to play the game, both on and of the pitch. -

Satellite TV News S051 7RU Ctober 20Th and Unusual Sightings on Intelsat Certain of the PAS -3R 803 © 27°W

FROM THE CLARKE BELT ROGER BUNNEY 35 GRAYLING MEAD FISHLAKE ROMSEY, HANTS Satellite TV News S051 7RU ctober 20th and unusual sightings on Intelsat certain of the PAS -3R 803 © 27°W. Checking across the 1830 sighting from the Otransponders atI 1.590GHz horizontal Capsis Beach Hotel at NTSC standard picttires from an aircraft, hills, then I 2.735GHz horizontal close-ups of military installations, a tank and an November 3rd though it airfield. The 1800 hours sightings continued without looked rather warmer any audio and ceased transmission with a `Globecast than Romsey in NY' and the pictureS then cut. The following day late November! Orion is afternoon and up appeared pictures though this time often carrying NTSC of an unusual aircraft, prop to rear taxiing along a feeds in NTSC for MBC The unmanned surveillance aircraft Live TV surveillance images from the runway in the desert in the rising sun. Lifting off and back into the UK from seen on tests via 27°W aircraft. yet more airborne pictures - as before the camera around 1730, another in featured sighting lines and other inlaid data. A clear analogue - OK if subsequent discussion with a learned source revealed you speak Arabic...the that this was an unatanned surveillance aircraft world hasn't gone totally undergoing tests prior to use across former digital! James Yugoslavia. The then present, manned, air surveillance Broughton (Yateley) aircraft were being spotted with missile laser sighting modified his Horizon to and these are being Withdrawn. To whom these Horizon motor mount pictures were intended isn't known and unusually on his dish with an they were carried inI the clear, analogue! additional 150mm New reader GaiTy Crawford (Kennoway, Fife) actuator drive on top has a second-hand 1H dish and I dB noise LNB which lets him hinge the During the UK Thrust SSC land RTP Lisbon and a news feed via Eutelsat feeding a Pace receiver. -

6. Africa Cup of Nations Stadiums

6. Africa Cup of Nations stadiums The first African Cup of Nations (CAN) was organised in 1957 and has been held every two years since 1968. 16 teams have participated in each tournament since 1998. In 2010 the Confederation of African Football (CAF) decided to move the CAN to uneven years to avoid the event clashing with the FIFA World Cup. Figure 6.1: Africa Cup of Nations stadiums 2000-2010 Number of Used Venues Number of New or Major Renovated Venues 7 666 6 6 5 4 44 4 44 3 2 1 1 0 1 0 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 As the figure above shows, the CAN’s host countries have over the last ten years tended to use four to six venues – in contrast to UEFA Euro, in which 16 teams also participate but UEFA’s requirements calls for at least eight stadiums. In the last six CAN tournaments all final venues have had a capacity over 45,000 and an average capacity of just over 58,000, which is comparable to the requirements UEFA has for the stadiums that stage the UEFA Euro final. However, the average capacity of the smallest venues used for the CAN is just 19,500 seats, which differs from UEFA’s minimum requirement of 30,000 seats. Both Tunisia and Egypt, who hosted CAN in 2004 and 2006 respectively, already had a decent number of stadiums available and did not make any major investments in new stadiums. Tunisia hosted the Mediterranean Games in 2001 and leading up to these games they constructed Stade de 7 Novembre, which after the 2011 revolution is now named Stade Olympique de Radès. -

Channel Package Orbital Position Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD 1+

Orbital Channel Package Satellite Language SD/HD/UHD Position EUTELSAT 1+1 13° EAST HOT BIRD UKRAINIEN SD CLEAR INTERNATIONAL 13D EUTELSAT 24 TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 2M MONDE 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN FIT & DANCE RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN HITS 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 4 FUN HITS RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 4 FUN TV RR Media 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT Cyfrowy 4 FUN TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD POLONAIS SD CLEAR Polsat 13C EUTELSAT 5 SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT 8 KANAL 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 8 KANAL EVROPE 13° EAST HOT BIRD RUSSE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT 90 NUMERI SAT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13B EUTELSAT AB CHANNEL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C ABN 13° EAST EUTELSAT ARAMAIC SD CLEAR HOT BIRD 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI AL 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE HD CLEAR OULA EUROPE 13B EUTELSAT ABU DHABI 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR SPORTS 1 13C EUTELSAT ABU DHABI ARABE, 13° EAST HOT BIRD SD CLEAR SPORTS EXTRA ANGLAIS 13C EUTELSAT ADA CHANNEL Sky Italia 13° EAST HOT BIRD ITALIEN SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT AHL-E-BAIT TV 13° EAST HOT BIRD PERSAN SD CLEAR FARSI 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA EUROPE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13D EUTELSAT AL AOULA MIDDLE SNRT 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR EAST 13D EUTELSAT AL ARABIYA 13° EAST HOT BIRD ARABE SD CLEAR 13C EUTELSAT -

Uefa Champions League 2012/13 Season Match Press Kit

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE 2012/13 SEASON MATCH PRESS KIT Galatasaray AŞ SC Braga Group H - Matchday 2 Ali Sami Yen Spor Kompleksi, Istanbul Tuesday 2 October 2012 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Contents Previous meetings.............................................................................................................2 Match background.............................................................................................................3 Match facts........................................................................................................................4 Squad list...........................................................................................................................6 Head coach.......................................................................................................................8 Match officials....................................................................................................................9 Fixtures and results.........................................................................................................10 Match-by-match lineups..................................................................................................12 Group Standings.............................................................................................................14 Competition facts.............................................................................................................16 Team facts.......................................................................................................................17 -

Unclassified DSTI/ICCP/TISP(97)7/FINAL

Unclassified DSTI/ICCP/TISP(97)7/FINAL Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques OLIS : 24-Jun-1999 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Dist. : 28-Jun-1999 __________________________________________________________________________________________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY Unclassified DSTI/ICCP/TISP(97)7/FINAL COMMITTEE FOR INFORMATION, COMPUTER AND COMMUNICATIONS POLICY Working Party on Telecommunication and Information Services Policies CONDITIONAL ACCESS SYSTEMS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ACCESS English text only 79578 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/ICCP/TISP(97)7/FINAL FOREWORD The following report was presented to the Working Party on Telecommunication and Information Services Policies (TISP) in September 1997 and was subsequently forwarded, in March 1998, to the Committee for Information, Computer and Communications Policy (ICCP), who agreed to its declassification through a written procedure. The report was prepared by Mr. Shigeyoshi Wakabayashi of the OECD’s Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry. It is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. Copyright OECD, 1999 Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or part of this material should be made to: Head of Publications Service, OECD, 2 rue André-Pascal, 75775 Paris Cedex 16, France. 2 DSTI/ICCP/TISP(97)7/FINAL TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD................................................................................................................................................. -

PRESS KIT @EURO2016 Wednesday 2 March 2016 #Lerendezvous 100 Days to Go

PRESS KIT @EURO2016 Wednesday 2 March 2016 #LeRendezVous 100 days to go Table of Contents UEFA European Football Championship ...................................................................................... 3 History of the competition .............................................................................................................. 3 Champions of Europe ..................................................................................................................... 4 UEFA EURO 2016 ........................................................................................................................... 5 I. Event identity ................................................................................................................................ 5 II. Match schedule ............................................................................................................................. 8 III. Facts and figures ..................................................................................................................... 10 IV. EURO 2016 steering group...................................................................................................... 11 V. EURO 2016 SAS: structure and organisation ........................................................................... 12 VI. Host cities ................................................................................................................................ 15 VII. Stadiums ............................................................................................................................... -

Copyright, Competition and Development

Copyright, Competition and Development Report by the Max Planck Institute for Intellectual Property and Competition Law, Munich December 2013 Preliminary note: The preparation of this Report has been mandated by the World Intellectual Property Organization to the Max Planck Institute and has been released in December 2013. Most of the information that is provided in the Report was collected in the second half of 2012 and has only partially been updated until summer 2013. This Report is authored by Professor Josef Drexl, Director of the Max Planck Institute. Many other scholars at the Institute took part in the research that led to this report. These include in particular Doreen Antony, Daria Kim and Moses Muchiri, as well as Dr Mor Bakhoum, Filipe Fischmann, Dr Kaya Köklü, Julia Molestina, Dr Sylvie Nérisson, Souheir Nadde‐Phlix, Dr Gintarė Surblytė and Dr Silke von Lewinski. The author will be happy to receive comments on the Report. These may relate to any corrections that are needed regarding the cases cited in the Report or additional cases that would be interesting and that have come up more recently. It is planned to publish the Report in a revised version in form of a book at a later stage. Comments can be sent to [email protected]. As regards agency and court decisions, the author would highly appreciate if these decisions were delivered in electronic form. Structure of this Document: Summary of the Report 2 Report 13 Annex: Questionnaire 277 1 Summary of the Report 1 Introduction (1) This text presents a summary of the Report of the Max Planck Institute for Intellectual Property and Competition Law on “Copyright, Competition and Development”. -

Progress in the Must-Offer Debate? Exclusivity in Media and Communication

LEGAL OBSERVATIONS OF THE EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Progress in the Must-offer Debate? Exclusivity in Media and Communication by Alexander Scheuer and Sebastian Schweda EDITORIAL “We’re in a good position!” This increasingly popular phrase is meant to transmit a sense of optimism; optimism that a company or branch of industry is in a position to spot opportunities in new markets or optimism that success will continue despite changes in the market. The markets involved may be defined according to geographical, technical or content-related criteria. In the audiovisual sector, for example, broadcasters are currently battling it out for a share in the various forms of distribution of audiovisual media services and the new markets that are being created as a result. In order for a company that wants to provide audiovisual media services to be well positioned, what it needs more than anything else is content that is of interest to consumers. The key to success for such a company is its ability to offer such content on an exclusive basis, in other words if it owns an exclusive right to distribute it. At the same time, however, it must also position itself in the distribution market, for it needs to send the content to the customer in order to convert its exclusive right into financial reward. This is the theme tackled by this IRIS plus, which looks at the various dimensions of exclusivity in media and communication. This IRIS plus considers the current debate on whether the obligation to transmit (must-carry) certain content should be replaced or at least supplemented by an obligation to offer such content (must-offer). -

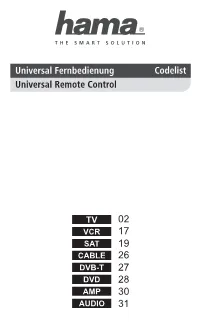

Hama Universal 8-In-1 Remote Control Code List

02 17 19 26 27 28 30 31 TV 01 ACCENT 0301 2551 2791 3601 ANGA 0411 4791 ACCUPHASE 2791 ANGLO 0301 3601 3831 ACEC 2741 ANITECH 0051 0301 1111 2361 ACTION 0051 0301 2091 2391 2391 2551 2581 2791 3811 3601 3831 4731 ADCOM 2711 ANSONIC 5301 5291 0301 1181 ADMIRAL 0051 0301 0621 0741 2551 2581 2631 2741 0981 1131 1571 2571 2791 3601 3881 5581 3661 3831 3881 4641 AOC 0051 2391 4261 ADVENTURA 0411 AR SYSTEM 2551 2791 3321 4761 ADVENTURI 0411 ARC EN CIEL 1981 1991 2091 2341 ADYSON 0051 2141 2391 3911 2591 2641 2681 3921 4731 ARCAM 2141 2641 3911 3921 AEA 2551 2791 4271 AEG 3531 3681 ARCELIK 5591 AGASHI 3831 3911 3921 ARCON 3531 AGB 2141 ARCTIC 5591 AGEF 2571 ARDEM 2551 2791 3541 AIKO 0301 2551 2751 2791 ARISTONA 0051 2471 2551 2741 3601 3831 3891 3911 2791 3921 ARSTIL 5591 AIM 2551 2791 3681 3721 ART TECH 0051 3841 ARTHUR-MARTIN 0621 0771 3881 AKAI 5301 5291 0051 0161 ASA 1101 1371 1381 1471 0301 0411 0561 0671 2571 2951 3881 4631 0741 0871 0991 1001 4641 ASBERG 0051 1111 1571 2551 1271 1291 1491 2141 2581 2791 2321 2361 2371 2391 ASORA 0301 3601 2551 2751 2791 3331 ASTON 4281 3541 3601 3681 3711 ASTRA 0301 2551 2791 3721 3831 3881 3891 ASTRELL 5081 3901 3911 3921 4791 5581 ASUKA 2141 2361 3831 3911 3921 AKASHI 3601 ATD 3841 AKIBA 2361 2551 2791 ATLANTIC 0051 1901 2551 2791 AKITO 2551 2791 3111 3911 AKURA 0051 0301 0881 0891 ATORI 0301 3601 2361 2551 2791 3541 ATORO 0301 3601 3831 AUCHAN 0621 0771 3881 ALARON 3911 AUDIOSONIC 0051 0301 1181 2091 ALBA 5301 5291 0051 0301 2141 2361 2551 2591 1181 1571 1681 2141 2631 2791 3331 3541 2361 2371 2491