Mwft F 1 7 1 a I 0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLENN MILLER ORCHESTRA Highlights

GLENN MILLER ORCHESTRA Highlights Glenn Miller was born on March 1, 1904, in Clarinda, Iowa. Glenn Miller originally wrote the music for Moonlight Serenade (later to become his theme song) as an exercise when he was studying with noted arranger, Joseph Schilinger. The first Glenn Miller Orchestra, formed in 1937, was a financial failure. In March 1938, Glenn Miller launched his second band, and unlike the first band, it became an enormous success with multiple hit records and huge box office sales. At the height of the orchestra’s popularity, Glenn Miller disbanded his musical organization in 1942 to volunteer for the army. He then organized the famous Glenn Miller Army Air Force Band. On December 15, 1944, Major Glenn Miller took off in a single engine plane from England – against his better judgment – to precede his band to France, never to be seen again. The army officially declared him dead one year later. Due to popular demand, the Miller Estate authorized the formation of the present Glenn Miller Orchestra in 1956. In 1941, Glenn Miller and His Orchestra had more hit records in one year, including A String of Pearls, than anybody in the history of the recording industry. Although other songs had sold over a million record copies, in 1941 Glenn Miller’s recording of Chattanooga Choo Choo received the first Gold Record ever to be awarded. The Glenn Miller Orchestra has been “on the road” longer and more continuously than any other Big Band ever. The Glenn Miller Orchestra travels over 100,000 miles each year, playing nearly 300 dates. -

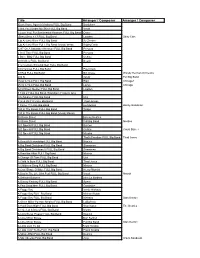

NSBA Convention Performances.Xlsx

NSBA Performances 1 Title Composer/ Arranger Publisher Grade Performing Group Director(s) Year Russian Christmas Music Alfred Reed, arr. James Curnow Hal Leonard 3.5 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 December Sky Erik Morales FJH Music 1.5 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 But for the Love of Ireland James Swearingen C.L. Barnhouse Company 3 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 Burma Patrol Karl King, ed. James Swearingen C.L. Barnhouse Company 3 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 Torrents of Fire Larry Neeck C.L. Barnhouse Company 3 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 Pandora Randall Strandridge Grand Mesa Music 2 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 An Irish Jig for Young Feet Travis J. Weller FJH Music 2 Ashland-Greenwood Senior High Band Jonathan Jaworski 2015 Girl from Ipanema Antonio Carlos Jobim/arr. Roger Holmes Hal Leonard Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Old Black Magic Arlene and Mercer/arr. Jerry Dotson Unpublished Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Pick up the Pieces arr. Victor Lopez Alfred Music Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Misty Burke and Garner/arr. Mike Lewis Alfred Music Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Blue Hue Dominic Spera C.L. Barnhouse Company Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Everlasting Gordon Goodwin Belwin Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 Bottom Line Blues Jon Phelps Kendor Music Publications Kearney High School Jazz Ensemble Nathan LeFeber 2015 All of Me Marks and Simon/arr. -

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“In the Mood”—Glenn Miller (1939) Added to the National Recording Registry: 2004 Essay by Cary O’Dell Glenn Miller Original release label “Sun Valley Serenade” Though Glenn Miller and His Orchestra’s well-known, robust and swinging hit “In the Mood” was recorded in 1939 (and was written even earlier), it has since come to symbolize the 1940s, World War II, and the entire Big Band Era. Its resounding success—becoming a hit twice, once in 1940 and again in 1943—and its frequent reprisal by other artists has solidified it as a time- traversing classic. Covered innumerable times, “In the Mood” has endured in two versions, its original instrumental (the specific recording added to the Registry in 2004) and a version with lyrics. The music was written (or written down) by Joe Garland, a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith who also composed “Leap Frog” for Les Brown and his band. The lyrics are by Andy Razaf who would also contribute the words to “Ain’t Misbehavin’” and “Honeysuckle Rose.” For as much as it was an original work, “In the Mood” is also an amalgamation, a “mash-up” before the term was coined. It arrived at its creation via the mixture and integration of three or four different riffs from various earlier works. Its earliest elements can be found in “Clarinet Getaway,” from 1925, recorded by Jimmy O’Bryant, an Arkansas bandleader. For his Paramount label instrumental, O’Bryant was part of a four-person ensemble, featuring a clarinet (played by O’Bryant), a piano, coronet and washboard. Five years later, the jazz piece “Tar Paper Stomp” by Joseph “Wingy” Manone, from 1930, beget “In the Mood’s” signature musical phrase. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

Instead Draws Upon a Much More Generic Sort of Free-Jazz Tenor

1 Funding for the Smithsonian Jazz Oral History Program NEA Jazz Master interview was provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. JON HENDRICKS NEA Jazz Master (1993) Interviewee: Jon Hendricks (September 16, 1921 - ) and, on August 18, his wife Judith Interviewer: James Zimmerman with recording engineer Ken Kimery Date: August 17-18, 1995 Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution Description: Transcript, 95 pp. Zimmerman: Today is August 17th. We’re in Washington, D.C., at the National Portrait Galley. Today we’re interviewing Mr. Jon Hendricks, composer, lyricist, playwright, singer: the poet laureate of jazz. Jon. Hendricks: Yes. Zimmerman: Would you give us your full name, the birth place, and share with us your familial history. Hendricks: My name is John – J-o-h-n – Carl Hendricks. I was born September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, the ninth child and the seventh son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. My father was a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the AME Church. Zimmerman: Who were your brothers and sisters? Hendricks: My brothers and sisters chronologically: Norman Stanley was the oldest. We call him Stanley. William Brooks, WB, was next. My sister, the oldest girl, Florence Hendricks – Florence Missouri Hendricks – whom we called Zuttie, for reasons I never For additional information contact the Archives Center at 202.633.3270 or [email protected] 2 really found out – was next. Then Charles Lancel Hendricks, who is surviving, came next. Stuart Devon Hendricks was next. Then my second sister, Vivian Christina Hendricks, was next. Then Edward Alan Hendricks came next. -

Anticommercialism in the Music and Teachings of Lennie Tristano

ANTICOMMERCIALISM IN THE MUSIC AND TEACHINGS OF LENNIE TRISTANO James Aldridge Department of Music Research, Musicology McGill University, Montreal July 2016 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS © James Aldridge 2016 i CONTENTS ABSTRACT . ii RÉSUMÉ . iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . v PREFACE . vi INTRODUCTION . 1 LITERATURE REVIEW . 8 CHAPTER 1 Redefining Jam Session Etiquette: A Critical Look at Tristano’s 317 East 32nd Street Loft Sessions . 19 CHAPTER 2 The “Cool” and Critical Voice of Lennie Tristano . 44 CHAPTER 3 Anticommercialism in the Pedagogy of Lennie Tristano . 66 CONCLUSION . 86 BIBLIOGRAPHY . 91 ii Abstract This thesis examines the anticommercial ideology of Leonard Joseph (Lennie) Tristano (1919 – 1978) in an attempt to shed light on underexplored and misunderstood aspects of his musical career. Today, Tristano is known primarily for his contribution to jazz and jazz piano in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He is also recognized for his pedagogical success as one of jazz’s first formal teachers. Beyond that, however, Tristano remains a peripheral figure in much of jazz’s history. In this thesis, I argue that Tristano’s contributions are often overlooked because he approached jazz creation in a way that ignored unspoken commercially-oriented social expectations within the community. I also identify anticommercialism as the underlying theme that influenced the majority of his decisions ultimately contributing to his canonic marginalization. Each chapter looks at a prominent aspect of his career in an attempt to understand how anticommercialism affected his musical output. I begin by looking at Tristano’s early 1950s loft sessions and show how changes he made to standard jam session protocol during that time reflect the pursuit of artistic purity—an objective that forms the basis of his ideology. -

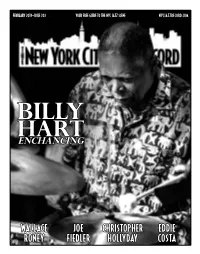

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives

Sun Valley Serenade Orchestra Wives t’s funny how music can define an entire come one of Miller’s biggest hits, “Chattanooga We also get some wonderful Harry Warren and era, and Glenn Miller’s unique sound did Choo Choo,” which, in the film, is a spectacu- Mack Gordon songs, including “At Last” (the Ijust that. It is not possible to think of World lar production number with Dandridge and The castoff from Sun Valley Serenade), “Serenade War II without thinking of the Miller sound. It Nicholas Brothers. Another great new song, “At in Blue,” “People Like You and Me,” and the was everywhere – pouring out of jukeboxes, Last,” was also recorded for the film, but wasn’t instant classic, “I’ve Got a Gal in Kalamazoo.” radios, record players. Miller had been strug- used, except as background music for several The latter was, like “Chattanooga Choo Choo,” gling in the mid-1930s and was dejected, but scenes. The song itself would end up in the nominated for an Oscar for Best Song. It knew he had to come up with a unique sound next Miller film. lost to a little Irving Berlin song called “White to separate him from all the others – and, of Christmas.” course, the sound he came up with was spec- “Chattanooga Choo Choo” hit number one on tacular and the people ate it up. His song the Billboard chart in December of 1941 and George Montgomery’s trumpet playing was “Tuxedo Junction” sold 115,000 copies in one stayed there for nine weeks. The song was dubbed by Miller band member, Johnny Best week when it was released. -

Blues in the Blood a M U E S L B M L E O O R D

March 2011 | No. 107 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com J blues in the blood a m u e s l b m l e o o r d Johnny Mandel • Elliott Sharp • CAP Records • Event Calendar In his play Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare wrote, “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.” It is a lovely sentiment but one with which we agree only partially. So with that introduction, we are pleased to announce that as of this issue, the gazette formerly known as AllAboutJazz-New York will now be called The New York City Jazz Record. It is a change that comes on the heels of our separation New York@Night last summer from the AllAboutJazz.com website. To emphasize that split, we felt 4 it was time to come out, as it were, with our own unique identity. So in that sense, a name is very important. But, echoing Shakespeare’s idea, the change in name Interview: Johnny Mandel will have no impact whatsoever on our continuing mission to explore new worlds 6 by Marcia Hillman and new civilizations...oh wait, wrong mission...to support the New York City and international jazz communities. If anything, the new name will afford us new Artist Feature: Elliott Sharp opportunities to accomplish that goal, whether it be in print or in a soon-to-be- 7 by Martin Longley expanded online presence. We are very excited for our next chapter and appreciate your continued interest and support. On The Cover: James Blood Ulmer But back to the business of jazz. -

Title Arranger / Composer Arranger / Composer

Title Arranger / Composer Arranger / Composer (Back Home Again In) Indiana FULL Big Band Barduhn+ (I Got You) Under My Skin FULL Big Band Vocal (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons FULL Big Band Osser (Shes) Sexy + 17 FULL Big Band Lowden Stray Cats (Up A) Lazy River FULL Big Band Sy Zentner (Up A) Lazy River FULL Big Band (Vocal) Wess Bobby Darin 1237 On A Saturday Afternoon FULL Big Band Persons 2 At A Time FULL Big Band Persons 2 Bone BBQ FULL Big Band Cobine 20 Nickles FULL Big Band Beach 21st Century Schizoid Man FULL Big Band 23 Chuckles FULL Big Band Paul Clark 23 Red FULL Big Band Bill Chase Woody Herman Orchestra 23o N 82oW Full Big Band 25 Or 6 To 4 FULL Big Band Blair Chicago+ 25 Or 6 To 4 FULL Big Band Lamm Chicago 42nd Street Medley FULL Big Band Lowden 5 Foot 2 FULL Big Band (Trombone Feature) Amy 50's Medley FULL Big Band Unk 61st & Rich' It FULL Big Band Thad Jones+ 7 Come 11 FULL Big Band Henderson Benny Goodman 720 In The Books FULL Big Band Wolpe 720 In The Books FULL Big Band (Vocal) Mason 88 Basie Street Sammy Nestico 88 Basie Street Full Big Band Nestico 920 Special FULL Big Band Bunton 920 Special FULL Big Band Collins Count Basie+ 920 Special FULL Big Band Murphy A That's Freedom FULL Big Band Thad Jones A Beautiful Friendship FULL Big Band Nestico A Big Band Christmas FULL Big Band Strommen A Big Band Christmas II FULL Big Band Strommen A Brazilian Affair FULL Big Band Mintzer A Change Of Pace FULL Big Band Unk A Child Is Born FULL Big Band Thad Jones A Childrens Song FULL Big Band Mintzer A Cool Shade Of Blue -

BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER FIRST-CLASS MAIL Box 52252 U.S

IN THIS ISSUE: An interview with BILL TOLE BIG * k Reviews of BOOKS AND RECORDS to consider BAND ★ A SMALL GROUPS JUMP TRIVIA QUIZ NEWSLETTER ★ LETTERS TO THE EDITOR about PAT FRIDAY, LORRAINE ELLIOTT, VIBES, TURNTABLES, BALLROOMS & OTHERS BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER FIRST-CLASS MAIL Box 52252 U.S. POSTAGE Atlanta, GA 30355 PAID Atlanta, GA Permit No. 2022 % \\ V % BIG BAND JIMP VOLUME LXXIV BIG BAND JUMP NEWSLETTER MAY-J UNE 2001 BILL TOLE INTERVIEW The Background For years we’ve seen the name Bill Tole listed as a member of the trombone section of various bands recorded on the west coast, then we became ac quainted with two CDs he had released with a solid band under his own name. Little by little, as information tends to accumulate, we discovered that Bill Tole is the brother of singer Nancy Knorr, who works with the Bill Tole as Bill Tole Jimmy Dorsey orchestra directed by Jim Miller. We also found out that Bill has a brother who is also a trombonist, and also works in the west coast studios. We got to know Bill Tole on a one-to-one basis when he led a Tommy Dorsey style orchestra on a spring BBJ cruise on the S.S. Rembrandt. We didn’t know until then that he’d portrayed Tommy Dorsey in a feature motion picture years earlier, assuming the Dorsey mannerisms, and of course playing the Dorsey music. He is a personable, easy-to-know musician who is fully dedicated to just that.... being the best musician he can be. -

![THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1947 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.002E]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2195/the-jerry-gray-story-1947-updated-jun-15-2018-version-jg-002e-1692195.webp)

THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1947 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.002E]

THE JERRY GRAY STORY – 1947 [Updated Jun 15, 2018 – Version JG.002e] January 26, 1947 [Sunday]: Jerry Gray arranged tunes made famous by Glenn Miller for New York City-based “Here’s To Ya” broadcast over the CBS radio network, January 26, 1947, 2:30 – 3:00 pm local time, performed by the Phil Davis Orchestra [including Trigger Alpert and Bernie Privin] and the Hires Hands vocal group [including Bill Conway]. Sponsored by Hires Root Beer. Moonlight Serenade – arranged by Jerry Gray Don’t Sit Under The Apple Tree – arranged by Jerry Gray Moonlight Cocktail – arranged by Jerry Gray A String Of Pearls – arranged by Jerry Gray Serenade In Blue – arranged by Jerry Gray In The Mood – arranged by Jerry Gray Chattanooga Choo Choo – arranged by Jerry Gray _______________ Harrisburg Telegraph [Harrisburg, Pennsylvania], Jan 18, 1947, Page 19: NEW SUNDAY MUSICAL SHOW HEARD ON WHP ‘Here’s To Ya’ Opens Jan. 26; Stars Louise Carlyle, Phil Hanna, Phil Davis “Here’s To Ya,” sparkling half-hour of popular and familiar music, featuring Contralto Louise Carlyle, Baritone-Emcee Phil Hanna, Phil Davis’ orchestra, and the Hires Hands singing group, starts on the Columbia network and WHP Sunday, January 26, 2:30-3 p.m. “Here’s To Ya” will be the first of a series of new shows to be added to the WHP schedule during the first few weeks of 1947 daytime schedule. Time and all information on the new programs will be announced in the near future on this page. Louise Carlyle, feminine star of “Here’s To Ya,” got her first big break several years ago as vocalist with her brother Russ’ orchestra.