Translating and Exegeting Hebrew Poetry: Illustrated with Psalm 70

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Psalms Psalm

Cultivate - PSALMS PSALM 126: We now come to the seventh of the "Songs of Ascent," a lovely group of Psalms that God's people would sing and pray together as they journeyed up to Jerusalem. Here in this Psalm they are praying for the day when the Lord would "restore the fortunes" of God's people (vs.1,4). 126 is a prayer for spiritual revival and reawakening. The first half is all happiness and joy, remembering how God answered this prayer once. But now that's just a memory... like a dream. They need to be renewed again. So they call out to God once more: transform, restore, deliver us again. Don't you think this is a prayer that God's people could stand to sing and pray today? Pray it this week. We'll pray it together on Sunday. God is here inviting such prayer; he's even putting the very words in our mouths. PSALM 127: This is now the eighth of the "Songs of Ascent," which God's people would sing on their procession up to the temple. We've seen that Zion / Jerusalem / The House of the Lord are all common themes in these Psalms. But the "house" that Psalm 127 refers to (in v.1) is that of a dwelling for a family. 127 speaks plainly and clearly to our anxiety-ridden thirst for success. How can anything be strong or successful or sufficient or secure... if it does not come from the Lord? Without the blessing of the Lord, our lives will come to nothing. -

Psalm 70 — an Urgent SOS

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Sunday School Placerita Baptist Church 2006 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 70 — An Urgent SOS 1.0 Introducing Psalm 70 y Psalm 70 is almost identical to Psalm 40:13-17. 9 Psalm 70 is the third to the last psalm in Book 2, while Psalm 40 is the second to the last psalm in Book 1. 9 “David appears to have written the full-length Psalm [40], and also to have made this excerpt from it, and altered it to suit the occasion.”— Charles Haddon Spurgeon, The Treasury of David, 3 vols. (reprint; Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, n.d.), 2/1:203. y Psalm 71 has no heading, so some commentators believe that Psalms 70 and 71 should be treated as one psalm. 9 “Hasten” (70:1, 5; 71:12) translates an unusual Hebrew word that occurs only once outside Psalms (1 Samuel 20:38). It occurs in Psalms 22:19; 38:22; 40:13 (= 70:1); and 141:1. 9 “Shame” occurs in 70:2, 3; 71:13, 24. y The psalm heading (“for a memorial”) is also found on Psalm 38. Perhaps the psalm was sung in conjunction with a sacrifice that would help “remind” the Lord of the psalmist’s request (cf. Leviticus 2:2; 24:7; 1 Chronicles 16:4). y Psalm 70 is a very short version of the message of Psalm 69. 2.0 Reading Psalm 70 (NAU) 70:1 A Psalm of David; for a memorial. -

Psalm 70:1-5 Hurry, Lord, Help!

Psalm 70:1-5 Hurry, Lord, Help! Book II concludes with a three psalm finale. Psalm 70 brings the “save-me” psalms to a quick and decisive climax. Psalm 71 follows with the joyful prayer of a resilient saint who expresses lifelong confidence in the Lord. Psalm 72 is a royal psalm dedicated to Solomon’s reign with a prophetic vision of the coming Messiah, the ideal king, who will rule and reign over the global Kingdom of God. Psalm 70 brings the worshiper back to a theme that has dominated Book II. The human condition is fallen and broken. We are in danger from every conceivable angle, from our own sinful nature to a vast array of enemies who lurk in the shadows ready to pounce. The cry, “save me!” has run through Book II as a dominate theme. It is fitting then that a quick spontaneous cry for help should bring these deliverance psalms to a clear finish. Save Me Hasten, O God, to save me; come quickly, Lord, to help me. Psalm 70:1 The plea for help remains even after great psalms of hope and salvation. David has given us an exhilarating sense of the grand sweep of redemption and creation (Ps 65) and a compelling invitation to join all the earth in shouting praises and singing hymns to God for his awesome deeds (Ps 66). David unites the blessing of God and the mission of God in a redemptive trajectory that encompasses all the nations (Ps 67) and leads us in a rousing crescendo of praise (Ps 68). -

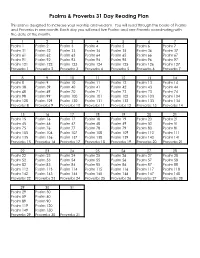

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3

Commentary on Psalms - Volume 3 Author(s): Calvin, John (1509-1564) Calvin, Jean (1509-1564) (Alternative) (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Calvin found Psalms to be one of the richest books in the Bible. As he writes in the introduction, "there is no other book in which we are more perfectly taught the right manner of praising God, or in which we are more powerfully stirred up to the performance of this religious exercise." This comment- ary--the last Calvin wrote--clearly expressed Calvin©s deep love for this book. Calvin©s Commentary on Psalms is thus one of his best commentaries, and one can greatly profit from reading even a portion of it. Tim Perrine CCEL Staff Writer This volume contains Calvin©s commentary on chapters 67 through 92. Subjects: The Bible Works about the Bible i Contents Commentary on Psalms 67-92 1 Psalm 67 2 Psalm 67:1-7 3 Psalm 68 5 Psalm 68:1-6 6 Psalm 68:7-10 11 Psalm 68:11-14 14 Psalm 68:15-17 19 Psalm 68:18-24 23 Psalm 68:25-27 29 Psalm 68:28-30 33 Psalm 68:31-35 37 Psalm 69 40 Psalm 69:1-5 41 Psalm 69:6-9 46 Psalm 69:10-13 50 Psalm 69:14-18 54 Psalm 69:19-21 56 Psalm 69:22-29 59 Psalm 69:30-33 66 Psalm 69:34-36 68 Psalm 70 70 Psalm 70:1-5 71 Psalm 71 72 Psalm 71:1-4 73 Psalm 71:5-8 75 ii Psalm 71:9-13 78 Psalm 71:14-16 80 Psalm 71:17-19 84 Psalm 71:20-24 86 Psalm 72 88 Psalm 72:1-6 90 Psalm 72:7-11 96 Psalm 72:12-15 99 Psalm 72:16-20 101 Psalm 73 105 Psalm 73:1-3 106 Psalm 73:4-9 111 Psalm 73:10-14 117 Psalm 73:15-17 122 Psalm 73:18-20 126 Psalm 73:21-24 -

Psalms Book Two

Theopolis Bible Translations 2 Psalms Book Two — TRANSLATION BY James B. Jordan MISSION— Theopolis Institute teaches men and women to lead cultural renewal by renewing the church. Participants in its various programs—its courses, conferences, and publications—will gain competence to read the Bible imaginatively, worship God faithfully, and engage the culture intelligently. CONTACT— a P.O. Box 36476, Birmingham, AL 35236 a theopolisinstitue.com e [email protected] t @theopolisinstitute Introduction The translation here presented is a work in progress. We hope to get feedback from those who use this material. In this Introduction, we set forth how we are doing this and why. The Structure of the Psalter To begin with, the structure of the Psalter. The book of Psalms as we have it today is not the psalter used at Solomon's Temple, but the completed and reorganized psalter for the Second Temple, the Temple after the exile. This is clear from Psalm 137, which was written at the exile. It is also clear in that psalms by David are found scattered throughout the whole psalter. The psalter used in Solomon's Temple may well have been arranged quite differently, but while that psalter was inspired and authoritative for that time, what we have today is a rearranged and completed psalter, equally inspired and authoritative, as well as final. We don't know whom God inspired to produce the final psalter. We can guess at Ezra, since he was a priest, and much involved with setting up the Second Temple order right after the return from Babylon. -

Fr. Lazarus Moore the Septuagint Psalms in English

THE PSALTER Second printing Revised PRINTED IN INDIA AT THE DIOCESAN PRESS, MADRAS — 1971. (First edition, 1966) (Translated by Archimandrite Lazarus Moore) INDEX OF TITLES Psalm The Two Ways: Tree or Dust .......................................................................................... 1 The Messianic Drama: Warnings to Rulers and Nations ........................................... 2 A Psalm of David; when he fled from His Son Absalom ........................................... 3 An Evening Prayer of Trust in God............................................................................... 4 A Morning Prayer for Guidance .................................................................................... 5 A Cry in Anguish of Body and Soul.............................................................................. 6 God the Just Judge Strong and Patient.......................................................................... 7 The Greatness of God and His Love for Men............................................................... 8 Call to Make God Known to the Nations ..................................................................... 9 An Act of Trust ............................................................................................................... 10 The Safety of the Poor and Needy ............................................................................... 11 My Heart Rejoices in Thy Salvation ............................................................................ 12 Unbelief Leads to Universal -

Daily Evening Prayer for Holy Week Wednesday, March 31, 2021

Daily Evening Prayer for Holy Week Wednesday, March 31, 2021 Confession of Sin The Officiant says to the people Dear friends in Christ, here in the presence of Almighty God, let us kneel in silence, and with penitent and obedient hearts confess our sins, that we may obtain forgiveness by his infinite goodness and mercy. Most merciful God, we confess that we have sinned against you in thought, word, and deed, by what we have done, and by what we have left undone. We have not loved you with our whole heart; we have not loved our neighbors as ourselves. We are truly sorry and we humbly repent. For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, have mercy on us and forgive us; that we may delight in your will, and walk in your ways, to the glory of your Name. Amen. The Priest alone stands and says Almighty God have mercy on you, forgive you all your sins through our Lord Jesus Christ, strengthen you in all goodness, and by the power of the Holy Spirit keep you in eternal life. Amen. The Invitatory and Psalter All stand Officiant O God make speed to save us. People O Lord, make haste to help us. Glory to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit: as it was in the beginning, is now, and will be for ever. Amen. O Gracious Light Phos hilaron O gracious light, pure brightness of the everliving Father in heaven, O Jesus Christ, holy and blessed! Now as we come to the setting of the sun, and our eyes behold the vesper light, we sing your praises, O God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. -

THE TRIBULATION PSALM with Verse References

THE TRIBULATION PSALM With Verse References DAY ONE 1) Psalm 8:1 O Lord, our Lord, How excellent is Your name in all the earth, Who have set Your glory above the heavens! 2) Psalm 97:9 For You, Lord, are most high above all the earth; You are exalted far above all gods. 3) Psalm 89:11 The heavens are Yours, the earth also is Yours; The world and all its fullness, You have founded them. 4) Psalm 102:25 Of old You laid the foundation of the earth, And the heavens are the work of Your hands. DAY TWO 5) Psalm 77:11 I will remember the works of the Lord; Surely I will remember Your wonders of old. 6) Psalm 93:2 Your throne is established from of old; You are from everlasting. 7) Psalm 75:1 We give thanks to You, O God, we give thanks! For Your wondrous works declare that Your name is near. 8) Psalm 48:10 According to Your name, O God, So is Your praise to the ends of the earth; Your right hand is full of righteousness. DAY THREE 9) Psalm 92:1-2 It is good to give thanks to the Lord, And to sing praises to Your name, O Most High; To declare Your lovingkindness in the morning, And Your faithfulness every night. 10) Psalm 143:8 Cause me to hear Your lovingkindness in the morning, For in You do I trust; Cause me to know the way in which I should walk, For I lift up my soul to You. -

Liturgical Introductions to the Psalms Revising As of May 2017

Liturgical Introductions to the Psalms Revising as of May 2017 - Brief introductions for use when singing or reading from the Psalter Terry L. Johnson 2 Liturgical Introductions to the Psalms Terry L. Johnson 3 On the Psalms Generally St. Basil (330–379) “A Psalms is the calm of souls, the arbiter of peace: it stills the stormy waves of thought. It softens the angry spirit and sobers the intemperate. A Psalm cements friendship; it unites those who are at variance; it reconciles those who are at enmity. For who can regard as an enemy the man with whom he has joined in lifting up one voice to God? Psalmody therefore provides the greatest of all good things, even love, for it has therefore invented concerted singing as a bond of unity, and fits the people together in the concord of one choir. A psalm puts demons to flight; it summons the angels to our aid; it is a weapon in the midst of alarms by night, a rest from the toils of day; it is a safeguard for babes, a decoration for adults, a comfort for the aged, a most fitting ornament for women. It makes deserts populous and market-places sane. It is an initiation to novices, growth to those who are advancing, a confirmation to those who are being perfected. It is the voice of the church; it gladdens festivals, it creates godly sorrow. For a Psalm calls forth tears from a stony heart. A Psalm is the employment of angels, heavenly converse, spiritual incense. What mayest thou not learn thence? The heroism of courage; the integrity of justice; the gravity of temperance; the perfection of prudence; the manner of repentance; the measure of patience; in a word every good thing thou canst mention. -

1 Kings &2 Chronicles W/Associated Psalms(Part 1)

1 Kings &2 Chronicles w/Associated Psalms(Part 1) Kings Purpose : The nation deserved the exile but restoration was possible through full repentance. Outline : 1.1:1-1.11:43 – Failure and Hope in Solomon’s Years (Solomon’s Wisdom, Solomon’s Women) 1.12:1-2.17:41 – Failure and Hope in Divided Years (Elijah and Elisha, Fall of Samaria in the north) 2.18:1-2:25:30 – Failure and Hope in Judah’s Final Years (Fall of Jerusalem in the south) Author : Unknown (Jewish tradition says Jeremiah) Date : Reign of Solomon – 970-922…Fall of Samaria – 722…Fall of Jerusalem…586 Book written while in exile (maybe around 550) Chronicles Purpose : To direct the restoration of the kingdom during the post-exilic period. Outline : 1.1:1-1.9:44 – Genealogies of God’s People (From Adam to David to Zerubbabel) 1.10:1-2.9:31 – United Kingdom (Saul, David, Solomon) 2.10:1-2:28:26 – Divided Kingdom (Fall of Samaria and Jerusalem) 2.29:1-2.36:23 – Reunited Kingdom (Cyrus’ Edict) Author : Some suggest there was a single “chronicler” for Chronicles and for Ezra-Nehemiah (perhaps Ezra himself). There are definite similarities, but also distinctions. Date : United Monarchy – 1050…Divided Monarchy – 922…Fall of Samaria – 722…Fall of Jerusalem – 586…Cyrus Edict – 538…Date of Composition, maybe 500-400 BC Notes about the Kings of Israel (north) and Judah (south) : The northern kingdom (Israel) was less stable politically than the southern kingdom (Judah). Israel only lasted for 209 years vs. 345 years for Judah. -

1 Psalms 69-70 – John Karmelich 1. This Is One Of

Psalms 69-70 – John Karmelich 1. This is one of those lessons that best starts by first giving the title: "What does it mean practically to be followers of Jesus?" Yes we are to be witnesses for Him, but what exactly are we supposed to do about that on a daily basis? What can we expect to happen to us if we have committed our lives to Him? Those are the simple issues this lesson takes on. ☺ a) As opposed to the last number of psalms that focused on God and what He can and will do in our lives, the focus of these psalms is back on us. These psalms state in effect that if we are committed to serving God how do we deal with that responsibility? b) It is to say in effect, "OK, God I know that I have committed my life to serving You and I am overwhelmed by what that entails." This psalm states in effect that we as humans are weak creatures. In order for us to make a difference for God, we need His help. This psalm is in effect a prayer request for God to help us to make a difference for Him. 2. You may find it interesting that Psalm 69 is the second most quoted psalm in the New Testament after Psalm 22. The references in Psalm 69 mainly tie to specific events of Jesus life. OK, so what? The answer is this psalm reminds us of the realization by Jesus himself as a man (and also the apostles as well) of the overwhelming cost to our own lives of being a follower of Christ.