Fall 2019 • No. 73 Issue No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicken Tikka Seasoning

1 / 5 Chicken Tikka Seasoning Chicken tikka curry - Serves 4. Before cooking: Peel and slice 1 medium-sized onion. Crush 5 garlic cloves. Peel and finely grate 3 tbsp of fresh ginger. Dice 4 .... Chicken Tikka Masala is thought to have been created by a Bangladeshi chef in Glasgow in the 1960s. It's a spicy, tomato-based dish seasoned with garlic, .... An easiest and aromatic homemade tikka masala spice mix for the popular tikka masala sauce or curry and dry rub for vegetable kebabs or baked tofu. ... Tags: best chicken tikka masala recipeeasy chicken tikka masalahow to .... This recipe is passed on through generations and perfected each time for the best results. From the traditional chicken tikka or paneer, to meat .... Shop Mr Kooks Zesty Tikka Rub - 1.23 Oz from Vons. Browse our wide selection of Indian ... Seasoning, Chicken Tikka, Medium Spicy. Authentic Indian cuisine.. A combination of spices are used to marinate the chicken before the meat is cooked in a gravy-like spiced sauce. Origins. Chicken Tikka Curry .... Shop for Simply Asia Indian Essentials Chicken Tikka Masala Seasoning Mix at Kroger. Find quality products to add to your Shopping List or order online for .... It owes its name to that heavily-spiced sauce, as masala is an Indian term for a mixture of spices. You can find Chicken Tikka Masala at every .... Spices Used in Recipe · Kashmiri red chilli powder (Deghi Mirch) · Saffron (Kesar) · Green Chillies (Hari Mirch) · Cassia bark · Chaat Masala · Garam Masala .... Homemade tandoori masala spice mix, a staple for Indian butter chicken, ... I needed this mix for a butter chicken recipe. -

Indian Masala Roast Turkey with Spiced Trimmings, Makhani Gravy and a Mango and Cranberry Chutney

INDIAN MASALA ROAST TURKEY WITH SPICED TRIMMINGS, MAKHANI GRAVY AND A MANGO AND CRANBERRY CHUTNEY INGREDIENTS PREPARATION Whole Turkey/Turkey crown 1. In a large baking tray place chunky slices of onion in the middle. The turkey will rest on here. Add the cinnamon stick and bay leaf Marinade to the tray. 4 tbsp Ginger, garlic paste 4 tbsp cumin and coriander powder 2. Mix all the marinade ingredients together, place turkey on top of 2 tsp turmeric onions and pour over the marinade reserving about a third of the 2 tsp garam masala mixture for the gravy. Leave to marinade for at least 6 hours or 2 tsp tandoori masala overnight. Seeds from 5 cardamom pods, crushed 1 tsp dried fenugreek leaves 3. Mix together all the stuffing ingredients, then either place under 3 tbsp Greek yoghurt the skin or make stuffing balls for around the turkey to decorate. 2 fresh lemons Salt and pepper 4. Pre-heat oven and cook turkey covered in foil according to its Squeeze of runny honey weight. Olive oil For lining the tray 5. Once cooked, leave to rest for at least 30 minutes before carving Cinnamon stick & bay leaf with a damp tea towel. 2 medium white onions Recipe continues overleaf Stuffing: (optional) 50/50 lamb mince and turkey mince Garlic/ginger Ajwain seeds Fresh coriander Coriander and cumin powder Turmeric by Nisha Parmar INDIAN MASALA ROAST TURKEY WITH SPICED TRIMMINGS, MAKHANI GRAVY AND A MANGO AND CRANBERRY CHUTNEY INGREDIENTS PREPARATION Garlic and chaat crispy roast Garlic and chaat crispy roast potatoes potatoes Maris piper potatoes, cut in quarters 1. -

Pondi Essential Menu 5 29.Pages

Pondicherithe essential menu breakfast breakfast frankie masala eggs & cilantro chutney wrap | choice of dosa wrap [gf] or carrot roti [v] 7 | + lamb 10 railway omelet ”everything but the kitchen sink” |choice of carrot roti [v] or pondi salad [gf] [v] 10| + lamb 13 khichri ✓ [gf] seven grains slow stewed with vegetables, ginger, turmeric, herbs, yogurt & warm spices 10 avocado dosa [gf] [v] roasted mushrooms, avocado masala, mango chutney | summer sambar 14 green dosa [gf] [v] sautéed greens, pumpkin seed chutney, avocado masala | summer sambar 12 egg dosa [gf] open face crêpe smeared with spinach purée, egg, cheese, vegetables & sesame 10 pani poori semolina puffs, mango cumin broth with lentil vegetable filling 8 snacks,sandwiches & salads samosa 5 VEG [v] sweet potato & pea with tomato kasundi | NON-VEG chicken & garbanzo with cumin yogurt pav bhaji Mumbai street fav! vegetable masala bhaji | toasted pumpkin buns 8 chili lettuce wraps ✓ sichuan pepper peanut masala with choice of paneer or chicken 12 madras chicken wings [gf] oven roasted with black pepper, sesame, amchur & tamarind chutney, cumin yogurt 13 frankies | choice of: desi fries or pondi salad or sambar a classic mumbai street wrap, choice of dosa wrap [gf] [v] or carrot roti [v] sabzi [v] rotating seasonal vegetables 10 chicken cilantro, fenugreek, tomato & garam masala in egg washed wrap 12 ghee burger | choice of : desi fries | pondi salad | summer sambar 10 choice of: ghee fried chicken or paneer with onion masala, mango chutney & fresh herbs pickle pizza pickled local -

Herbs & Spices

www.TheCookingMAP.com About 22 Authors 1. Healthy Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/olivia-lopez 2. Bread Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/emma-kim 3. Dessert Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/sophia-garcia 4. Fruit and Vegetable Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/emily-chan 5. Drink Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/nathan-nelson 6. Pasta and Noodles Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/jack-lemmon 7. Salad Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/henry-fox 8. Appetizer and Snack Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/ella-martinez 9. BBQ & Grilling Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/ellie-lewis 10. Breakfast and Brunch Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/anna-lee 11. Dinner Recipe Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/victoria-lopez 12. Everyday Cooking Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/sofia-rivera 13. Holiday Food Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/chloe-webb 14. {Cooking by Ingredient Land}: https://www.thecookingmap.com/lily-li 15. Lunch Recipe Land : https://www.thecookingmap.com/lucy-liu 16. Main Dish Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/benjamin-tee 17. Meat and Poultry Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/nora-perry 18. Seafood Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/mila-mason 19. Side Dish Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/amelia-vega 20. Soup and Stew Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/liam-fox 21. U.S.A Recipe Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/lucas-neill 22. World Cuisine Land: https://www.thecookingmap.com/avery-moore Herbs & Spices 365 Enjoy 365 Days with Amazing Herb & Spice Recipes in Your Own Herb & Spice Cookbook (Herbs & Spices- Volume 1) Lily Li Copyright: Published in the United States by Lily Li/ © LILY LI Published on November 12, 2018 All rights reserved. -

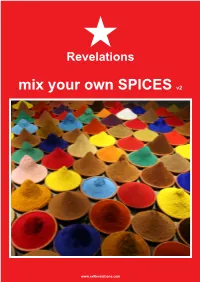

Mix Your Own SPICES V2

Revelations mix your own SPICES v2 www.svRevelations.com Achaar Ka Masala Yield: 1 cup Masala, a ground spice mixture is perhaps the most common and the easiest way of using 1 tablespoon red chilly powder whole spices. It takes a little effort to combine spices at home and make a spice blend. In the multitude of spice mix, Achaar Ka Masala stands out for its bright color. 1 tablespoon turmeric powder 3 tablespoons mustard seeds (sarson) 1 tablespoon fennel seeds (saunf) In a heavy bottom pan dry roast the mustard seeds for 1 - 2 minutes. Transfer to a bowl. Next dry roast the fennel seeds till aroma is released, keep on stirring while roasting. 1 tablespoon fenugreek seeds (methi dana) Transfer to the same bowl as mustard seeds. 1 tablespoon carom seeds (ajwain) Similarly, dry roast fenugreek seeds, carom seeds and nigella seeds on by one. 2 teaspoons nigella seeds (kalonji) Add the roasted spices in a blender and grind to a coarse powder. Transfer the masala mix to a bowl. Add salt, amchur, red chili powder and turmeric powder. 1 tablespoon salt (or to taste) Stir to combine. Store the Achaar Masala in a clean, dry airtight jar at room temperature. Make sure to use dry spoon to scoop out the masala. Achaar Masala has a shelf life of more than 6 months if stored at ideal conditions. Adobo Seasoning Yield: 7 tablespoons Prep Time: 10 minutes 2 tablespoons salt This seasoning is used often in Mexican and Filipino dishes. 1 tablespoon paprika 2 teaspoons ground black pepper In a bowl, stir together the salt, paprika, black pepper, onion powder, oregano, cumin, garlic 1 1/2 teaspoons onion powder powder, and chili powder. -

Appetizers Tandoori Specialities Chef Special's Karahi Dishes Bhoona

Appetizers Karahi Dishes Jaipuri Dishes Vegetable pakora…….………………………………...3.95 A rich flavored dish made with bell peppers, onions, Semi dry dish made from tender pieces of tikka cooked Chicken Pakora………………………………………...5.95 tomatoes, fresh ginger and garlic. with bell peppers, onions, tomato and mushrooms. Gobhi Pakora…………………………………………..5.95 Chicken Karahi………………………………………...9.95 Chicken Jaipuri………………………………………...9.95 Vegetable Samosa Chana………………………..….….5.95 Lamb Karahi…………………………………………...9.95 Lamb Jaipuri…………………………………………...9.95 Cheese Pakora……………………………………...…..6.95 Vegetable Karahi..……………………………………..9.95 Prawn and Mushroom Jaipuri………………………….9.95 Tikki Chana………………………………………...…..5.95 Chicken or Lamb Karahi Saag….……………………...9.95 Shrimp Jaipuri………………………………………...10.95 Chana Poori………………………………………….....5.95 Goat Karahi…………………………………………….9.95 Fish Jaipuri……………………………………………10.95 Mushroom Poori…………………………………….....5.95 Paneer Karahi……………………………………..........9.95 Prawn Poori………………………………………...…..5.95 Shrimp Karahi………………………………………...10.95 Vegetable dishes Papadoms…………………………………………...….4.95 Shrimp Saag……………………………………..........10.95 Vegetables cooked fresh with authentic Indian herbs and Soup of the day……………………………………..….3.95 spices. Fish Pakora…………………………………………...14.95 Bhoona Dishes Mix Vegetable…………………………………………8.95 A tomato based rich in flavor dish made with chef’s secret Shahi Paneer…………………………………………...8.95 Tandoori Specialities recipe and special herbs and spices. Saag Paneer (spinach and Cheese)……………………..8.95 chicken marinated in garlic, lemon juice, jeera and -

Soups 5 Starters Tandoor Clay Oven Breads Drinks 3

SOUPS 5 STARTERS RAITA & PAPPADAM BIRBALI SHORBA ASSORTED PAKORAS 6 HARE MASALE KA RAITA 4 homemade shorba. tomato. vegetables. deep fried. yogurt. cucumber. tomato. onion. orange segments. roasted cumin. SAMOSA 5 PAPPADAM 2 MULLIGATAWANY SOUP crispy pyramids. spiced potato. traditional roasted. pea. lentil. pepper spice. deep fried. PAPPADAM ROASTED / FRIED VEG COCONUT ZAFRANI SAMOSA CHAAT 7 MASALA 4 vegetables. coconut. saffron. samosas. chickpeas. yogurt. chutney. roasted onion. chili. cilantro. spices. GINGER PEPPER CHICKEN SOUP BOONDI RAITA 4 chicken. ginger spice. PAPDI CHAAT 7 yogurt. boondi. crispy flour chips. chickpeas. yogurt. chutney. spices. ALOO TIKKI CHAAT 7 TANDOOR CLAY OVEN potato patty. chickpeas. yogurt. BREADS chutney. spices. PANEER TIKKA / PANEER ACHARI VADA PAO 7 TANDOORI ROTI 2 TIKKA 12 potato bonda. chili garlic. bun. whole wheat bread. tandoor marinated paneer. onion. pepper. preparation. tomato. pineapple. grilled. BEET CUTLETS 7 culcutta specialy. kasundi mustard. TAWA PARATHA 3 TANDOORI MURGH (half/full) 9/16 pan fried. whole wheat bread. home style. a well known delicacy. VEG HARA BARA KEBAB 7 RUMALI ROTI 4 MURGH TIKKA 13 spinach, cheese & potato patties. thin hand tossed bread. chicken. spice variety. grilled. aromatic herbs. crispy. iron griddle. MURGH MALAI TIKKA 13 CHOLE BHATURE 13 NAAN chicken. cream. lemon juice. grilled. spiced chickpea curry with puffed leavened flour bread. tandoor bread. preparation. TIKKA PLATTER 16 (plain 2 / butter 2 / garlic 3 / bullet - chili chicken. assortment. CHICKEN LOLLIPOP 6 & cilantro 3) drums. spice variety. crispy. RESHMI KEBAB 13 LACHCHA/PUDINA PARATHA 3 minced chicken. skewered. spices. CHICKEN CHAAT 8 multilayer bread. clarified butter. grilled. tikka. flour crisps. chickpeas. yogurt. -

We're Open 7 Days a Week

We guarantee satisfaction. CONTEMPORARY INDIAN CUISINE Tulsi is a name of rare quality and distinction. “Tulsi” is a holy plant from the basil family. It belongs to the Hindu religion as a paramount symbol of worship. (6th in an order of eight scared objects). Tulsi contacts important medicicinal properties used inthe sure and precention of many illnesses. (including malaria and heart disease). It’s value is such that the word “Tulsi” has come to mean “that which cannot be compared.” Tulsi contemporary Insian cuisine offers you the finest curries without compare. Halal meat available. Home delivery services (conditions apply). We’re open 7 days a week. SURCHARGE APPLIES ON PUBLIC HOLIDAYS. WWW.TULSI.CO.NZ VEGETARIAN ENTRÉE ROASTED PAPADOM BASKET $2.50 Crispy lentil based pancake sprinkled with chaat masala. MASALA PAPADOM BASKET $2.50 Crispy lentil based pancaked topped with onion, tomato, cucumber and green coriander with chaat masala. ONION PAKORA $7.50 Onion fitters dipped in chickpea flour and deep fried until crispy. JEERA ALOO $7.50 Potato cubes tempered and sautéed with cumin seeds, Turmeric powder, lemon juice and garnished with green coriander. VEGETABLE PAKORA $7.50 Mixed vegetables dipped in spicy chickpea and flour and deep fried. VEGETABLE SAMOSA $7.00 Green peas and smashed potatoes filled in triangular pastry. ALOO COCKTAIL $7.50 Crushed boil potatoes, mixed with curry leaves, bread crumbs and deep-fried. TANDOORI PANEER $9.00 Cottage cheese marinated in yoghurt and ginger garlic paste and roasted in the tandoori with capsicums and onion. TANDOORI MUSHROOM $9.00 Mushrooms marinated in yoghurt, ginger, garlic and combination of spices and roasted in tandoori oven. -

Indian Tapas and Tandoori Grills

INDIAN TAPAS AND TANDOORI GRILLS Choori Chaat (v) / 5.50 Chicken Wings (GF) - 3 pcs / 5.50 Signature street food snack of papdi, cornflakes, herbs Tandoori Chicken wings tossed in Hot garlic sauce spiced potato, mango chutney, tamarind chutney, mint chutney, yoghurt and pomegranate pearls Tandoori Chicken Tikka (GF) – 3 pcs / 6 sitting on a bed of rice poppadum Chicken tikka, marinated in Tandoori spice mix with saffron and charcoal grilled. Aloo Papdi Chaat (v) / 4.50 Street food snack of crisp flour pancake, potato, Chicken Malai Tikka Afghani (GF) – 3 pcs / 6 chick-pea tabbouleh, tamarind chutney and yoghurt Tandoor roasted very mild chicken tikka, marinated in Onion Bhaji (Vegan) (GF) – 3 pcs/ 4.50 cream cheese, yogurt and aromatic spices Contains nuts Shredded onion in gram flour batter, crisp golden fried Chicken Momo Tandoori. red chilli chutney – 4 pcs / 6 Vegetable Samosa (Vegan) – 2 pcs/ 5 Chicken mince dumpling, steamed, marinated in garden peas and spiced potato in a crisp pastry - vegan tandoori masala and charcoal grilled Lasooni Paneer Shashlik with peppers (v) (GF) / 6.5 Tawa Fish Ajwaini (GF) – 2 pcs (GF) / 7 Cottage cheese, peppers and onion spiced in tandoori Tilapia Fish Fillet, thin gram-flour coating, pan-fried marinade, char-grilled in clay oven Salmon Tikka (GF) – 2 pcs / 8 Butternut Squash Seekh Kebab (Vegan) / 6 Grilled Norwegian Salmon in a mild Butternut squash, cauliflower, carrots and beans, sautéed, Tandoori mix marinade, chargrilled in clayoven mashed, skewered and grilled over charcoal Tandoori King Prawn -

Soups Starters

Soups 1. Murgh Shorba 59 Kč Chicken broth with coriander and served with shreds of chicken. 2. Dal Shorba 55 Kč Traditional Indian lentil soup Starters 3. Vegetable Samosa 2 pcs. 85 Kč Triangular pastry stuffed with spicy potatoes, peas and dry fruits. 4. Onion Bhaji 4 pcs. 85 Kč Sliced Onions dipped in chick pea batter and deep fried. 5. Roasted Pappadam 2 pcs. 45 Kč Paper-thin lentil crepes roasted in a tandoor oven. 6. Masala Pappadam 2 pcs. 69 Kč Paper-thin lentil crepes roasted in a tandoor oven with tomatoes onion and coriander 7. Vegetable Pakora 89 Kč Fresh Vegetables smothered in chick pea batter and deep fried. 8. Vegetable Platter (for 2 pers.) 199 Kč Mixed platter of 2 onion bhaji, mix vegetable pakora, and 2 samosa. 9. Tandoori Platter (for 2 pers.) 210 Kč Mixed platter of tangri chicken, chicken tikka, malai tikka 10. Chicken Tikka 4 pcs. 139 Kč Tender morsels of chicken marinated in yoghurt and tandoori masala then cooked in tandoori oven. 11. Malai Tikka 4 pcs. 157 Kč Chicken breast marinated with ginger, garlic, cream, cheese, cashew and cardamom, roasted in a tandoori oven. 12. Tandoori Prawn 6 pcs. 349 Kč Tiger prawn marinated in yoghurt, cinnamon and Indian spices, smoked in tandoori oven. From Tandoor Tandoor is not a name of recipe. It is actually a cooking method. A tandoor is a clay oven in which a hot fire is built. Marinated meat is lowered into the oven on long metal skewers. Then, it is cooked in this smoky and extremely hot environment. -

John Lewis Stock Number 77060109 Name Curry Night in Containing

John Lewis Stock Number 77060109 Curry Night In Containing:- Naga Chilli Sauce 220ml Name Mango and Chilli Dipping Sauce 220ml Korma Curry Paste 100g Tandoori Masala Mix 55g Naga Chilli Sauce Ingredients: Peaches (26%), Tomatoes, Onions, White wine vinegar, Sugar, Water, Cornflour, Salt, Garlic purée, Concentrated lime juice, Dried naga jolokia chillies. Mango and Chilli Dipping Sauce Ingredients: Mango chutney (40%) (Sugar, Mango, Cane sugar vinegar, Salt, Ginger, Raisins, Chilli powder, Ginger purée, Ginger powder, Garlic powder, Colour: Plain caramel), Sugar, Water, Lime pickle (8%) (Limes, Cotton seed oil, Salt, Mustard, Acetic acid, Fenugreek, Spices), Glucose syrup, Salt, Acetic acid, Chilli flakes, Thickener: Xanthan gum. Ingredients Korma Curry Paste Ingredients: Sunflower oil, Spirit vinegar, Onion, Salt, Ground coriander, Turmeric, Garam masala, Spices, Ground ginger, Chilli flakes, Cinnamon, Ginger purée, Garlic purée, Garlic powder, Onion powder. May contain traces of Nuts. Tandoori Masala Mix Ingredients: Coriander, Cumin, Paprika, Fenugreek, Turmeric, Black pepper, Chilli, Cinnamon, Cloves, Nutmeg, Bay leaves, Garlic granules. May contain traces of Sesame, Mustard and Celery. For allergens, see ingredients in bold Naga Chilli Sauce 220ml Mango and Chilli Dipping Sauce 220ml Net Quantity Korma Curry Paste 100g Tandoori Masala Mix 55g Country of Origin England Storage Instructions N/A Cottage Delight, Leekbrook, Leek, Staffordshire, ST13 Manufacturer’s name and address 7QF Instructions for use N/A Nutrition Labelling N/A Alcoholic Strength N/A Suitable for vegetarians Y Suitable for vegans Y Suitable for nut allergy sufferers N Suitable for gluten allergy sufferers Y Suitable to wheat allergy sufferers Y Suitable for egg allergy sufferers Y Suitable for dairy allergy sufferers Y Suitable for soya allergy sufferers Y Free from alcohol Y Free from artificial flavours Y Free from artificial colours Y . -

Ruby-Menu-2021.Pdf

APPETIZERS Tandoori Chicken Flatbread Tandoori Spiced Chicken, Spiced Onion Jam, Cilantro Yogurt 16.5 Vegetable Samosa Spiced Potato & Green Peas stuffed in Savoury Pastry 5.5 Vegetable Pakora Bell Pepper, Cauliflower & Potato Chickpea Flour Fritter 9 Onion Bhajia Fried Chickpea Flour Battered Onions 9 Goan Calamari Crisp Calamari, Ruby’s Special Sauce 14 Tandoori Roasted Lamb Gilafi Ginger, Garlic, Garam Masala, Peppers & Onions, Pomegranate 16.5 Beetroot Aloo Tikki Beetroot, Potato & Green Pea Fritter Tamarind Sauce 9.25 Cornmeal Crusted Chicken Wings Ginger Garlic Marinated, Lemon Juice, Green Cardamon 13 Chicken Samosa Minced Spiced Chicken & Green Peas stuffed in Savoury Pastry 6.5 Chicken Tikka Ginger, Garlic, Yoghurt, Tandoori Masala 13 Shrimp Pakora (5) Chickpea Flour Battered Shrimp 17 Zaffrani Paneer Tikka Housemade Paneer Cheese, Saffron Marinated 16.5 Crisp Coconut & Noodle Crusted Shrimp Tamarind Sauce 17 Chick Pea & Cream Cheese Bhajia Tamarind Sauce 9.5 Lazeez Mushroom Tikka Tandoor Roasted Mushrooms, Traditional Spice 15.5 Poppadoms & Chutneys 4.25 Biryani Basmati Rice with Fried Onion, Mint, & Spices, steamed over a slow fire, served with raita Shrimp 21.25 Fish 19.75 Beef 19.75 Lamb 19.75 Chicken 18.75 Vegetable 16.75 MODERN INDIAN ENTREES Ajwaini Jhinga Tandoor Cooked Prawns, Marinated in Ginger, Garlic, Caraway, Yoghurt, Vegetable Pulao, Kadai Sauce 30 Bharwan Simla Mirch Paneer & Vegetable Stuffed Bell Pepper 20 Goan Coconut Fish Curry Cumin, Coriander, Red Chilies 23 Samundari Rhatan Shrimp, Calamari, & Wahoo Garam Masala, Chili 26 Nalli Gosht Slow Braised Lamb Shank Green Chili, Onion, Ginger, Tomato 30 Lamb Chops Yoghurt, Garlic & Ginger Marinated, Cooked in the Tandoor 29 FROM THE TANDOOR Tandoori Fish Tikka Marinated with Spices & Yoghurt 21 Murgh Malai Kebab Marinated Chicken Thigh Cooked with Cheese & Yoghurt.