Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Thailand and Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RP: Sri Lanka: Hikkaduwa-Baddegama Section Of

Resettlement Plan May 2011 Document Stage: Draft SRI: Additional Financing for National Highway Sector Project Hikkaduwa–Baddegama Section of Hikkaduwa–Baddegama–Nilhena Road (B153) Prepared by Road Development Authority for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 May 2011) Currency unit – Sri Lanka rupee (Rs) Rs1.00 = $0.009113278 $1.00 = Rs109.730000 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank CEA – Central Environmental Authority CSC – Chief Engineer’s Office CSC – Construction Supervision Consultant CV – Chief Valuer DSD – Divisional Secretariat Division DS – Divisional Secretary ESD – Environment and Social Division GN – Grama Niladhari GND – Grama Niladhari Division GOSL – Government of Sri Lanka GRC – Grievance Redress Committee IOL – inventory of losses LAA – Land Acquisition Act LARC – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Committee LARD – Land Acquisition and Resettlement Division LAO – Land Acquisition Officer LARS – land acquisition and resettlement survey MOLLD – Ministry of Land and Land Development NEA – National Environmental Act NGO – nongovernmental organization NIRP – National Involuntary Resettlement Policy PD – project director PMU – project management unit RP – resettlement plan RDA – Road Development Authority ROW – right-of-way SD – Survey Department SES – socioeconomic survey SEW – Southern Expressway STDP – Southern Transport Development Project TOR – terms of reference WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Ha hectare km – kilometer sq. ft. – square feet sq. m – square meter NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

2.02 Rajasuriya 2008

ARJAN RAJASURIYA National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency, Crow Island, Colombo 15, Sri Lanka [email protected]; [email protected] fringing and patch reefs (Swan, 1983; Rajasuriya et al., 1995; Rajasuriya & White, 1995). Fringing coral reef Selected coral reefs were monitored in the northern, areas occur in a narrow band along the coast except in western and southern coastal waters of Sri Lanka to the southeast and northeast of the island where sand assess their current status and to understand the movement inhibits their formation. The shallow recovery processes after the 1998 coral bleaching event continental shelf of Gulf of Mannar contains extensive and the 2004 tsunami. The highest rate of recovery coral patch reefs from the Bar Reef to Mannar Island was observed at the Bar Reef Marine Sanctuary where (Rajasuriya, 1991; Rajasuriya, et al. 1998a; Rajasuriya rapid growth of Acropora cytherea and Pocillopora & Premaratne, 2000). In addition to these coral reefs, damicornis has contributed to reef recovery. which are limited to a depth of about 10m, there are Pocillopora damicornis has shown a high level of offshore coral patches in the west and east of the recruitment and growth on most reef habitats island at varying distances (15 -20 km) from the including reefs in the south. An increase in the growth coastline at an average depth of 20m (Rajasuriya, of the calcareous alga Halimeda and high levels of 2005). Sandstone and limestone reefs occur as sedimentation has negatively affected some fringing discontinuous bands parallel to the shore from inshore reefs especially in the south. Reef surveys carried out areas to the edge of the continental shelf (Swan, 1983; for the first time in the northern coastal waters around Rajasuriya et al., 1995). -

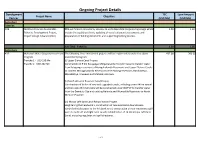

Ongoing Project Details

Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) Agriculture Fisheries ADB Northern Province Sustainable PDA will finance consultancy services to undertake detail engineering design which 1.59 1.30 Fisheries Development Project, include the updating of cost, updating of social safeguard assessments and Project Design Advance (PDA) preparation of bidding documents and supporting bidding process. Sub Total - Fisheries 1.59 1.30 Agriculture ADB Mahaweli Water Security Investment The following three investment projects will be implemented under the above 432.00 360.00 Program investment program. Tranche 1 - USD 190 Mn (i) Upper Elahera Canal Project Tranche 2- USD 242 Mn Construction of 9 km Kaluganga-Morgahakanda Transfer Canal to transfer water from Kaluganga reservoir to Moragahakanda Reservoirs and Upper Elehera Canals to connect Moragahakanda Reservoir to the existing reservoirs; Huruluwewa, Manakattiya, Eruwewa and Mahakanadarawa. (ii) North Western Province Canal Project Construction of 96 km of new and upgraded canals, including a new 940 m tunnel and two new 25 m tall dams will be constructed under NWPCP to transfer water from the Dambulu Oya and existing Nalanda and Wemedilla Reservoirs to North Western Province. (iii) Minipe Left Bank Canal Rehabilitation Project Heightening the headwork’s, construction of new automatic downstream- controlled intake gates to the left bank canal; construction of new emergency spill weirs to both left and right bank canals; rehabilitation of 74 km Minipe Left Bank Canal, including regulator and spill structures. 1 of 24 Ongoing Project Details Development TEC Loan Amount Project Name Objective Partner (USD Mn) (USD Mn) IDA Agriculture Sector Modernization Objective is to support increasing Agricultural productivity, improving market 125.00 125.00 Project access and enhancing value addition of small holder farmers and agribusinesses in the project areas. -

Assessment of Forestry-Related Requirements for Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of Tsunami-Affected Areas of Sri Lanka

ASSESSMENT OF FORESTRY-RELATED REQUIREMENTS FOR REHABILITATION AND RECONSTRUCTION OF TSUNAMI-AFFECTED AREAS OF SRI LANKA MISSION REPORT 10 – 24 MARCH 2005 SIMMATHIRI APPANAH NATIONAL FOREST PROGRAMME ADVISOR (ASIA-PACIFIC) FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................... 1 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... 1 2. Background......................................................................................................................... 2 3. Key features of the Mission and approach ...................................................................... 3 4. Impact of the Tsunami....................................................................................................... 4 4.1 General overview ............................................................................................................... 4 4.2 Natural habitats affected by the Tsunami .......................................................................... 5 5. The impact of the Tsunami on natural and manmade ecosystems................................ 7 5.1 Coastlines........................................................................................................................... 7 5.2 Home gardens ................................................................................................................... -

Safe & Secure Certified Level 1 Hotels by the Sri Lanka Tourism

SAFE & SECURE CERTIFIED LEVEL 1 HOTELS As at 14th January 2021 Published by Sri Lanka Tourism Development Authority No. Name District Category Hotel Website 1 Amaya Beach Batticaloa 4 Star [email protected]/[email protected] 2 Amaya Lake Matale 4 Star [email protected] 3 Amethyst Resort Batticaloa Tourist Hotel [email protected]/[email protected] 4 Ananthara Kaluthara Resort Kalutara 5 Star [email protected] / [email protected] 5 Ananthara Peace Heaven Resort Hambantota 5 Star [email protected] (Not sure this is GM email) 6 Ani Villas Dickwella Matara Tourist Hotel [email protected] 7 Ayurveda Paragon Galle Tourist Hotel [email protected] 8 Cape Weligama Matara Boutique Hotel [email protected] 9 Castlereagh Bungalow Nuwara Eliya Boutique Villa [email protected] 10 Cinnamon Benthota Beach Galle 4 Star [email protected] 11 Cinnamon Bey Kalutara 5 Star 12 Citrus Hikkaduwa Galle Tourist Hotel [email protected] 13 Connected Dreams Galle Bungalow [email protected] 14 Coral Sands Hotel Galle Tourist Hotel [email protected] 15 Dunkeld Bungalow Nuwara Eliya Boutique Villa [email protected] 16 Haritha Villas + Spa Galle Guest House [email protected] 17 Heritance Ahungalla Galle 5 Star [email protected] 18 Heritance Negambo Gampaha 5 Star [email protected]/[email protected] 19 Hibiscus Beach Hotel Kalutara 1 Star [email protected] 20 Insight Resort Ahangama. Galle Tourist Hotel [email protected] -

Sri Lanka Delights

Sri Lanka Delights Your consultant: Phone: E-mail: Anu Arora +91-9899685829 [email protected] Day 1 Airport - Colombo Upon arrival welcome and assistance by our representative and transfer to Colombo Hotel (01 hour drive) Colombo - A cozy mixture of the past and present, The Portuguese, Dutch and British have all left in their wake churches and monuments, names and religions, costumes and food and smatterings of their languages which have been absorbed into the speech of the Sri Lankan. Overnight: Colombo Hotel, Colombo Meals: Breakfast, Dinner Day 2 Colombo - Habarana After breakfast drive to Habarana (04 hours drive) en route visit Dambulla Cave Temple - Dating back to the 1st Century BC, this is the most impressive cave temple in Sri Lanka. The cave monastery, with its five sanctuaries, is the largest, best-preserved cave-temple complex in Sri Lanka. Inside the caves, the ceilings are painted with intricate patterns of religious images, following the contours of the rock. There are images of the Lord Buddha and bodhisattvas, as well as various gods and goddesses. Afternoon (optional) Village Tour in Sigiriya - At the start Traveling by bullock cart thorough typical dry Zone village then get on to traditional village boat for boat ride in the lake running through the village and get into their paddy fields & cultivation lands and experience how farmers working there and thereafter having Typical Sri Lankan village lunch serve by Banana or Nelum leaf in side of mud house and at last walking through the village to start point while experience the Village life. Overnight: Habarana Hotel, Habarana Meals: Breakfast, Dinner Day 3 Habarana - Kandy After breakfast proceeds to Sigiriya (20 min) climb Sigiriya rock fortress - Sigiriya was the capital city, built by parricidal King Kasyapa who reigned from 477-495 AD. -

Policy-Relevant Assessment of Community-Level Coastal Management Projects in Sri Lanka Kem Lowry! *, Nirmalie Pallewatte", A.P

Ocean & Coastal Management 42 (1999) 717}745 Policy-relevant assessment of community-level coastal management projects in Sri Lanka Kem Lowry! *, Nirmalie Pallewatte", A.P. Dainis# !Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of Hawaii, Porteus 107, 2424 Maile Way, Honolulu 96822, USA "Department of Zoology, Colombo University, Sri Lanka #Ministry of Cooperatives, Provincial Councils, Local Government and Indigenous Medicine, USA Abstract Community-level coastal management programs are being introduced in some countries as a practical strategy to respond to conditions of poverty and unsustainable resource use practices. Two recently developed Special Area Management (SAM) programs developed in Sri Lanka are part of this international trend. These two SAM programs were assessed to identify planning and early management issues that may be relevant to future projects. This paper examines general issues in assessing community-level projects. The particular focus is on a few issues of general relevance: community participation in the planning process; the adequacy of the boundary; quality of the technical analysis; adequacy of resource management activities; transparency of management decisions; community acceptance of the program; and sustainabil- ity of resource management activities. ( 1999 Published by Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction First-generation coastal management programs are most often characterized by &top-down' approaches to management. That is to say, coastal management programs are frequently organized and implemented by national and provincial levels of government, focused on large geographic areas and replete with mandates to subordinate levels of government and coastal resource users about how resources are to be used and hazards prevented. This &top-down' approach has been most successful * Corresponding author. -

Y%S ,Xld M%Cd;Dka;%Sl Iudcjd§ Ckrcfha .Eiü M;%H W;S Úfyi the Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY

Y%S ,xld m%cd;dka;%sl iudcjd§ ckrcfha .eiÜ m;%h w;s úfYI The Gazette of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka EXTRAORDINARY wxl 2072$58 - 2018 uehs ui 25 jeks isl=rdod - 2018'05'25 No. 2072/58 - FRIDAY, MAY 25, 2018 (Published by Authority) PART I : SECTION (I) — GENERAL Government Notifications SRI LANKA Coastal ZONE AND Coastal RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN - 2018 Prepared under Section 12(1) of the Coast Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Act, No. 57 of 1981 THE Public are hereby informed that the Sri Lanka Coastal Zone and Coastal Resource Management Plan - 2018 was approved by the cabinet of Ministers on 25th April 2018 and the Plan is implemented with effect from the date of Gazette Notification. MAITHRIPALA SIRISENA, Minister of Mahaweli Development and Environment. Ministry of Mahaweli Development and Environment, No. 500, T. B. Jayah Mawatha, Colombo 10, 23rd May, 2018. 1A PG 04054 - 507 (05/2018) This Gazette Extraordinary can be downloaded from www.documents.gov.lk 1A 2A I fldgi ( ^I& fPoh - YS% ,xld m%cd;dka;s%l iudcjd§ ckrcfha w;s úfYI .eiÜ m;%h - 2018'05'25 PART I : SEC. (I) - GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA - 25.05.2018 CHAPTER 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 THE SCOPE FOR COASTAL ZONE AND COASTAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 1.1.1. Context and Setting With the increase of population and accelerated economic activities in the coastal region, the requirement of integrated management focused on conserving, developing and sustainable utilization of Sri Lanka’s dynamic and resources rich coastal region has long been recognized. -

Minamata Initial Assessment Report Sri Lanka

Minamata Initial Assessment Report Sri Lanka July 2019 MIA Sri Lanka 1 Introduction Mercury - A Global Pollutant “Mercury is a chemical of global concern owing to its long- range atmospheric transport, its persistence in the environment once anthropogenically introduced, its ability to bioaccumulate in ecosystems and its significant negative effects on human health and the environment” (First preamble of the Minamata Convention on Mercury) Mercury is a naturally occurring chemical element with symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is commonly known as quicksilver, a shiny silvery metal and is the only metal that is liquid at room temperature and standard pressure. It is a heavy metal having a very low vapour pressure and slowly evaporates even at ambient temperature. Mercury exists as; Mercury occurs in its elemental form in the earth's crust but is more commonly found in the form of cinnabar (mercury Elemental/metallic sulphide). It may occur with other non-ferrous sulphide minerals mercury (zinc, lead, arsenic, gold, etc) and in trace quantities or as an Methyl mercury impurity in many other economically valuable materials including fossil fuels such as coal, gas, and oil. Moreover, Other organic or mercury combines with most metals to form alloys called inorganic compounds amalgams and these decompose on heating with volatilization of the metallic mercury. Once mercury has been released, it persists in the environment, cycling between air, land and water, and biomagnifies up the food chain. Sources and Paths of Mercury in the Environment MIA Sri Lanka 2 Mercury and mercuric compounds (particularly methyl mercury) have long been recognized as chemical substances, which have significant adverse health effects on humans and the environment. -

Research on Safty on Railway Level Crossing from Panadura to Galle

CHAPTER 3 METHOLODY OF STUDY All railway crossings from Panadura to Galle were identified using topo sheet which are published by the Department of survey. The collected details of railway stations cross checked from Railway Stations of Panadura, Aluthgama & Galle. A list of railway stations with location, Divisional Secretariat offices and related Police Stations are shown in Table 3.1 The level crossing locations & roads which were identified using topo sheet were clarified from Chief Engineers Office of Road Development Authority at Kalutara & Galle, Provincial Road Development Authorities of Western & Southern Provinces and relevant local authorities such as Municipal Councils, Urban Councils & Pradeshiya Sabhas. According to the collected data from above authorities & site investigation in survey stage the updated railway level crossing locations with road name, ownership & closest stations were indicated in Table 3.2 All railway level crossings within the project area were inspected & surveyed to collect data related to their safety for road users. For the purpose of studying the geometric conditions of the location including road and railway line existing safety measures, existing traffic controlling methods and their conditions, accidents and serious conflict situations records were surveyed. The data were collected as research survey form no.1 (Appendix A) To analyze the traffic data of the relevant location a traffic count survey was conducted on the railway level crossings. Due to large number of locations, the traffic count was limited to 15 minutes at each location for both directions. It was carried out as survey research form no. 2 (Appendix B). Accident records were collected from relevant Police station & public who are resident closer to the level crossing locations. -

Due to Heavy Rains in Past Few Days, Landslides and Floods in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Flood situation report (29/05/2017) using TerraSAR-X satellite data and publicly available sources Draft Prepared by International Water Management Institute (IWMI) Due to heavy rains in past few days, landslides and floods in Sri Lanka killed 151 people, 111 people still missing, displacing 100,000 and directly affecting 500,000 people across many districts according to the initial estimates by state- run Disaster Management Center. International Disaster Charter was activated by Disaster Management Centre (DMC) and coordinated by International Water Management Institute (IWMI)/CGIAR. The first satellite image obtained on 28-05-2017 by German Aerospace Centre (DLR) showed vast areas of standing flood waters along the Southern and South-Western Provinces. Initial estimates from satellite images indicate that Matara (49.3) and Kalutara with 31.6 km2 flooded area, are the worst affected districts followed by Galle (20.2 km2), Rathnapura (14.9 km2), Colombo (5.6 km2) and Gampaha (4.5 km2). Detailed Divisional Secretariat wise flood affected area for these six districts are given below. Kalutara is reeling under worst flood since 2003. Residents in affected pockets are reluctant to move away from flooded homes fearing safety of their belongings for potential theft. People in the town of Kalutara said that the water levels are still high and don’t expect to fall soon. “All access to our village is cut off completely, making it difficult event for anyone to reach,” told residents in Kalutara to IWMI. River Kalu Ganga is overflowing the bunds due to excess flow from upstream catchment area. As per meteorological/irrigation department forecast, water levels is expected to rise further within next 36 hours. -

Tourist Accommodation

Tourist Accommodation Number of SLTDA Registered Accommodation Establishments as at end March 2019 Classified Tourist Hotels Number of Number of Categorization 6% Establishments Rooms Unclassified Classified Tourist Others 41% Hotels Hotels 147 13,544 10% Five star 23 5,150 Four Star 23 2,438 Three Star 24 2,416 Boutique Guest Hotel and Houses Two Star 39 1,878 Villa 40% One Star 38 1,662 3% Tourist Hotel [Cite your source here.] (Unclassified) 242 10,446 Boutique Hotel 32 638 Tourist… 10,446 Boutique Villa 40 265 Rented Home 19 Rented Apartment 223 Guest House 969 10,594 Hostels 16 Bungalow 412 1,701 Home Stay Unit 1,434 Heritage Bungalow 4 19 Heritage Home 9 Heritage Home 3 9 Heritage Bungalow 19 Guest House 10,594 Home Stay Unit 476 1,434 Classified Tourist… 13,544 Hostels 2 16 Bungalow 1,701 Rented Apartment 70 223 Boutique Villa 265 Rented Home 6 19 Boutique Hotel 638 0 5,000 10,000 15,000 Number of Rooms Total 2,403 38,908 [Cite your source here.] The total number of SLTDA registered accommodation establishments as at 31st March 2019 was 2,403. The number of classified tourist Hotels was 147 and among them 23 were five-star hotels. The presence of small and medium enterprises is strong with guest houses, homestays and bungalows recording the highest number of registered establishments with 969, 476 and 412 respectively. The total room inventory was 38, 908. Classified tourist hotels (1-5 star) had the highest inventory of 13, 544 rooms. Geographical Distribution of Rooms of SLTDA Registered Tourist Establishments Number of Rooms Distribution (NRD) NRD > 7,000 7,000 > NRD > 5,000 5,000 > NRD > 3,000 3,000 > NRD > 1000 1,000 > NRD > 500 500 > NRD > 0 [Cite your source here.] [Cite your source here.] The map depicts the distribution of rooms in SLTDA registered tourist establishments within each district.