Ensuring Patients' Access to Care and Privacy: Are Federal Laws Protecting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Results of Elections Attorneys General 1857

RESULTS OF ELECTIONS OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL 1857 - 2014 ------- ※------- COMPILED BY Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP ------- ※------- (2016) 1 FOREWORD The Office of Attorney General of Minnesota is established by the constitution; its duties are set by the legislature; and its occupant is chosen by the voters. 1 The first question any historian of the office confronts is this: why is the attorney general elected and not appointed by the governor? Those searching for answers to this question will look in vain in the debates of the 1857 constitutional convention. That record is barren because there was a popular assumption that officers of the executive and legislative branches of the new state government would be elected. This expectation was so deeply and widely held that it was not even debated by the delegates. An oblique reference to this sentiment was uttered by Lafayette Emmett, a member of the Democratic wing of the convention, during a debate on whether the judges should be elected: I think that the great principle of an elective Judiciary will meet the hearty concurrence of the people of this State, and it will be entirely unsafe to go before any people in this enlightened age with a Constitution which denies them the right to elect all the officers by whom they are to be governed. 2 Contemporary editorialists were more direct and strident. When the convention convened in St. Paul in July 1857, the Minnesota Republican endorsed an elected judiciary and opposed placing appointment power in the chief executive: The less we have of executive patronage the better. -

Results of Elections Attorneys General 1857

RESULTS OF ELECTIONS OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL 1857 - 2010 ------- ※------- COMPILED BY Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP ------- ※------- (2013) 1 FOREWORD The Office of Attorney General of Minnesota is established by the constitution; its duties are set by the legislature; and its occupant is chosen by the voters. 1 The first question any historian of the office confronts is this: why is the attorney general elected and not appointed by the governor? Those searching for answers to this question will look in vain in the debates of the 1857 constitutional convention. That record is barren because there was a popular assumption that officers of the executive and legislative branches of the new state govern- ment would be elected. This expectation was so deeply and widely held that it was not even debated by the delegates. An oblique reference to this sentiment was uttered by Lafayette Emmett, a member of the Democratic wing of the convention, during a debate on whether the judges should be elected: I think that the great principle of an elective Judiciary will meet the hearty concurrence of the people of this State, and it will be entirely unsafe to go before any people in this enlightened age with a Constitution which denies them the right to elect all the officers by whom they are to be governed. 2 Contemporary editorialists were more direct and strident. When the convention convened in St. Paul in July 1857, the Minnesota Republican endorsed an elected judiciary and opposed placing appointment power in the chief executive: The less we have of executive patronage the better. -

Office Name Elected Officials in Ramsey County

Elected Officials in Ramsey County Term of Office Year of Next Office Name (Years) Election Federal President/ Vice President Donald Trump and Michael Pence 4 2020 US Senator Amy Klobuchar 6 2018 US Senator Al Franken 6 2020 US Congress- District 4 Betty McCollum 2 2018 US Congress- District 5 Keith Ellison 2 2018 State Senate- District 38 Roger Chamberlain 4 2020 Senate- District 41 Carolyn Laine 4 2020 Senate- District 42 Jason "Ike" Isaacson 4 2020 Senate- District 43 Charles "Chuck" Wiger 4 2020 Senate- District 53 Susan Kent 4 2020 Senate- District 64 Dick Cohen 4 2020 Senate- District 65 Sandy Pappas 4 2020 Senate- District 66 John Marty 4 2020 Senate- District 67 Foung Hawj 4 2020 Representative- District 38B Matt Dean 2 2018 Representative- District 41A Connie Bernardy 2 2018 Representative- District 41B Mary Kunesh-Podein 2 2018 Representative- District 42A Randy Jessup 2 2018 Representative- District 42B Jamie Becker-Finn 2 2018 Representative- District 43A Peter Fischer 2 2018 Representative- District 43B Leon Lillie 2 2018 Representative- District 53A JoAnn Ward 2 2018 Representative- District 64A Erin Murphy 2 2018 Representative- District 64B Dave Pinto 2 2018 Representative- District 65A Rena Moran 2 2018 Representative- District 65B Carlos Mariani 2 2018 Representative- District 66A Alice Hausman 2 2018 Representative- District 66B John Lesch 2 2018 Representative- District 67A Tim Mahoney 2 2018 Representative- District 67B Sheldon Johnson 2 2018 Governor / Lieutenant Governor Mark Dayton / Tina Smith 4 2018 Secretary of State Steve Simon 4 2018 State Auditor Rebecca Otto 4 2018 Attorney General Lori Swanson 4 2018 Judicial State Supreme Court- Chief Justice Lorie Skjerven Gildea 6 2018 State Supreme Court- Associate Justice Barry Anderson 6 2018 State Supreme Court- Associate Justice Margaret H. -

2018 Primary Election Consolidated Sample Ballot

CONSOLIDATED SAMPLE BALLOT A Sibley CountyB State of MinnesotaC August 14, 2018 State Partisan Primary Ballot 11 Sibley County, Minnesota August 14, 2018 Instructions to Voters: To vote, completely fill in the oval(s) next to your choice(s) like this: R This ballot card contains a partisan ballot and a nonpartisan ballot. On the partisan ballot you are permitted to vote for candidates of one political party only. 21 Republican Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party Party Federal Offices Federal Offices U.S. Senator U.S. Senator For term expiring January 3, 2025 For term expiring January 3, 2025 Vote for One Do not vote for Vote for One Roque "Rocky" De La Fuente Steve Carlson January 3, 2025 candidates of January 3, 2025 Rae Hart Anderson more than one Stephen A. Emery January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Jim Newberger party. Amy Klobuchar January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Merrill Anderson David Robert Groves 40 January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Leonard J. Richards 41 U.S. Senator January 3, 2025 Special Election for term expiring 42 January 3, 2021 U.S. Senator Vote for One Special Election for term expiring 43 January 3, 2021 Nikolay Nikolayevich Bey Vote for One January 3, 2021 Bob Anderson Christopher Lovell Seymore Sr. January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 Karin Housley Gregg A. Iverson January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 Tina Smith U.S. Representative January 3, 2021 District 7 Nick Leonard Vote for One January 3, 2021 Richard W. Painter Dave Hughes January 3, 2021 Ali Chehem Ali 51 Matt Prosch January 3, 2021 State Offices U.S. -

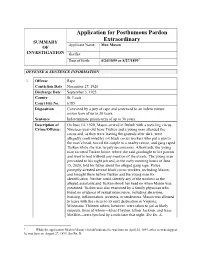

Application for Posthumous Pardon Extraordinary [Matter No

Application for Posthumous Pardon SUMMARY Extraordinary Applicant Name: Max Mason OF INVESTIGATION aka/fka: Date of Birth: 4/24/1899 or 8/27/18991 OFFENSE & SENTENCE INFORMATION 1. Offense Rape Conviction Date November 27, 1920 Discharge Date September 3, 1925 County St. Louis Court File No. 6785 Disposition Convicted by a jury of rape and sentenced to an indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Sentence Indeterminate prison term of up to 30 years. Description of On June 14, 1920, Mason arrived in Duluth with a traveling circus. Crime/Offense: Nineteen-year-old Irene Tusken and a young man attended the circus and, as they were leaving the grounds after dark, were allegedly confronted by six black circus workers who put a gun to the man’s head, forced the couple to a nearby ravine, and gang raped Tusken while she was largely unconscious. Afterwards, the young man escorted Tusken home, where she said goodnight to her parents and went to bed without any mention of the events. The young man proceeded to his night job and, in the early morning hours of June 15, 2020, told his father about the alleged gang rape. Police promptly arrested several black circus workers, including Mason, and brought them before Tusken and the young man for identification. Neither could identify any of the workers as the alleged assailants and Tusken shook her head no when Mason was presented. Tusken was also examined by a family physician who found no evidence of sexual intercourse, including abrasions, bruising, inflammation, soreness, or tenderness. Mason was allowed to leave with the circus to its next destination in Virginia, Minnesota. -

COVER PHOTOGRAPHER Tim Rummelhoff

SPRING 2008 IN THIS ISSUE Faculty, Student, and Alumni Profiles • Walter F. Mondale Celebration • Women in Section E A New Dean For a New Era The Law School Welcomes David Wippman. INTERIM DEANS Guy-Uriel E. Charles Fred L. Morrison DIRECTOR OF COMMUNICATIONS Cynthia Huff SENIOR EDITOR Corrine Charais DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Scotty Mann DIRECTOR OF ALUMNI RELATIONS AND ANNUAL GIVING Anita C. Foster CONTRIBUTING WRITERS Corrine Charais Brad Clary Anita Foster Susan Gainen Evan Johnson Sara Jones Frank Jossi Erin Keyes Muria Kruger Scotty Mann Steve Marchese Todd Melby Kit Naylor Mark Peña Bryan Seiler Pamela Tabar Jenna Zakrajsek COVER PHOTOGRAPHER Tim Rummelhoff PHOTOGRAPHERS: Anthony Brandenburg Trey Fortner Jayme Halbritter Perspectives is a general interest magazine published throughout the academic year for Dan Kieffer the University of Minnesota Law School community of alumni, friends, and supporters. Josh Kohanek Letters to the editor or any other communication regarding content should be sent Mark Luinenburg to Cynthia Huff ([email protected]), Director of Communications, University of Minnesota Law School, 229 19th Avenue South, N225, Minneapolis, MN 55455. Dan Marshall Mike Minehart The University of Minnesota is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal Tony Nelson access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, age, marital status, disability, public assistance status, Tim Rummelhoff veteran status, or sexual orientation. DESIGNER ©2008 by University of Minnesota Law School. Carr Creatives Lending a Helping Hand hen Fred and I talk to students we are trying to attract to the Law School, we tell them that one of the best ways to judge a law school is by the participation of its Walumni in the life of the school. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 12, 2011

Minnesota Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 12, 2011 FOR INFORMATION Gary Goldsmith – (651) 296-1721 Jeff Sigurdson – (651) 296-1720 CAMPAIGN FINANCE AND PUBLIC DISCLOSURE BOARD RELEASES FINAL PUBLIC SUBSIDY PAYMENT AMOUNTS FOR 2010 ELECTION During 2010 the Campaign Finance and Public Disclosure Board distributed $4,011,037 in public subsidy payments to 364 candidates running for state constitutional and legislative offices. The 364 candidates who received a public subsidy payment represent 86% of the 422 candidates who were on the general election ballot. A list of qualifying candidates and the payments they received is attached to this news release. Of the 465 candidates who filed for a state constitutional or legislative office in 2010, 416 (89%) signed voluntary agreements to abide by spending limits and other conditions required to be eligible for public subsidy of their campaigns. To qualify for public subsidy a candidate must: • be opposed at either the primary or general election, • appear on the general election ballot, • sign and file a public subsidy agreement with the Board to abide by applicable campaign expenditure limits, • and raise a specified amount in contributions of $50 or less from individuals eligible to vote in Minnesota. Money for the public subsidy program comes from the state general fund. A portion of public subsidy money is allocated to specific parties and districts based on taxpayer check-offs on income and property tax returns. By office and party, the total public subsidy payments totaled: - Continued - DFL RPM IPMN Governor $0 $515,953 $348,279 Attorney General $180,409 $0 $0 Secretary of State $67,214 $58,967 $0 State Auditor $67,214 $58,967 $0 State Senate $813,551 $618,818 $6,488 House of Representatives $754,680 $505,265 $15,226 Total $1,883,070 $1,757,972 $369,994 DFL = Democratic Farmer Labor RPM = Republican Party of Minnesota IPMN = Independence Party of Minnesota Note: No Green Party of Minnesota candidates qualified for a public subsidy payment in 2010. -

State of Minnesota Office of the Attorney General

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp STATE OF MINNESOTA OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL ANNUAL REPORT REQUIRED BY Minnesota Statute Sections 8.08 and 8.15 Subdivision 4 (2017) Fiscal Year 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................... 1 CIVIL LITIGATION....................................................................................................... 2 REGULATORY LAW AND PROFESSIONS............................................................... 8 GOVERNMENT LEGAL SERVICES............................................................................ 14 STATE GOVERNMENT SERVICES............................................................................ 27 CIVIL LAW..................................................................................................................... 39 APPENDIX A: Recap of Legal Services........................................................................ A-1 APPENDIX B: Special Attorney Appointments............................................................ B-1 APPENDIX C: Attorney General Opinions oflnterest .................................................. C-1 INTRODUCTION This report is intended to fulfill the requirements of Minnesota Statutes Sections 8.08 and 8.15, Subdivision 4, for Fiscal Year 2018 (FY 2018). The Attorney General's Office (AGO) is organized -

State Court School Desegregation Cases: the New Frontier

State Court School Desegregation Cases: The New Frontier 2020 Edition LawPracticeCLE Unlimited All Courses. All Formats. All Year. ABOUT US LawPracticeCLE is a national continuing legal education company designed to provide education on current, trending issues in the legal world to judges, attorneys, paralegals, and other interested business professionals. New to the playing eld, LawPracticeCLE is a major contender with its oerings of Live Webinars, On-Demand Videos, and In-per- son Seminars. LawPracticeCLE believes in quality education, exceptional customer service, long-lasting relationships, and networking beyond the classroom. We cater to the needs of three divisions within the legal realm: pre-law and law students, paralegals and other support sta, and attorneys. WHY WORK WITH US? At LawPracticeCLE, we partner with experienced attorneys and legal professionals from all over the country to bring hot topics and current content that are relevant in legal practice. We are always looking to welcome dynamic and accomplished lawyers to share their knowledge! As a LawPracticeCLE speaker, you receive a variety of benets. In addition to CLE teaching credit attorneys earn for presenting, our presenters also receive complimentary tuition on LawPracticeCLE’s entire library of webinars and self-study courses. LawPracticeCLE also aords expert professors unparalleled exposure on a national stage in addition to being featured in our Speakers catalog with your name, headshot, biography, and link back to your personal website. Many of our courses accrue thousands of views, giving our speakers the chance to network with attorneys across the country. We also oer a host of ways for our team of speakers to promote their programs, including highlight clips, emails, and much more! If you are interested in teaching for LawPracticeCLE, we want to hear from you! Please email our Directior of Operations at [email protected] with your information. -

Student Edition07-08.Qxp

CONTENTS Fun Facts About Minnesota ................................................................................................2 Minnesota State Symbols....................................................................................................3 State Historic Sites ............................................................................................................10 Governor’s Residence ......................................................................................................10 Historical Essay: The “Civic State” ..................................................................................11 Good Citizenship ..............................................................................................................13 Pledge of Allegiance and The National Anthem ..............................................................14 The United States Flag......................................................................................................15 Flag Etiquette ....................................................................................................................16 Presidents and Vice Presidents of the United States ........................................................18 Documentary History........................................................................................................19 The Mayflower Compact ............................................................................................19 Fundamental Orders of 1639 ......................................................................................20 -

Chapter Four

State Executive Offices Chapter Four Chapter Four State Executive Offices Governor ...................................................................................................... 286 Lieutenant Governor .................................................................................... 287 Attorney General .......................................................................................... 288 State Auditor ................................................................................................ 289 Secretary of State ......................................................................................... 290 Executive Councils and Boards ................................................................... 292 Executive Officers Since Statehood ............................................................ 293 Image provided by the Minnesota Historical Society Governor William Marshall was Minnesota's fifth governor, serving from January 8, 1866 until January 9, 1870. He was instrumental in securing suffrage for African Americans in Minnesota in 1869. StateExecutive Offices Chapter Four Chapter Four State Executive Offices OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR Mark Dayton (Democratic-Farmer-Labor) Elected: 2010 Term: Four years Term expires: January 2015 Statutory Salary: $120,303 St. Paul. Blake School, Hopkins; BA, cum laude, Yale University (1969); Teacher, New York City Public Schools; Legislative Assistant, Senator Walter Mondale; Commissioner, Minnesota Department of Economic Development; Commissioner, Minnesota Department of -

Camden Township 0010

SAMPLE BALLOT 11 Official Ballot State Primary Ballot Judge _____ Carver County, Minnesota August 14, 2018 Judge _____ Instructions to Voters: To vote, completely fill in the oval(s) next to your choice(s) like this ( ) 21 This is a partisan primary ballot. You are permitted to vote for candidates of one political party only. Republican Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party Party Do not vote for Federal Offices candidates of Federal Offices U.S. Senator more than one U.S. Senator For term expiring January 3, 2025 party. For term expiring January 3, 2025 Vote for One Vote for One Rae Hart Anderson Steve Carlson January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 Jim Newberger Stephen A. Emery January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 40 Merrill Anderson Amy Klobuchar January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 41 Roque "Rocky" De La Fuente David Robert Groves January 3, 2025 January 3, 2025 42 Leonard J. Richards U.S. Senator January 3, 2025 43 Special Election for term expiring January 3, 2021 U.S. Senator Vote for One Special Election for term expiring January 3, 2021 Nikolay Nikolayevich Bey Vote for One January 3, 2021 Bob Anderson Christopher Lovell Seymore Sr. January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 Karin Housley Gregg A. Iverson January 3, 2021 January 3, 2021 U.S. Representative Tina Smith District 6 January 3, 2021 Nick Leonard Vote for One January 3, 2021 Richard W. Painter A.J. Kern January 3, 2021 52 Ali Chehem Ali Patrick Munro January 3, 2021 Tom Emmer U.S. Representative District 6 State Offices Vote for One Governor and Lieutenant Ian Todd Governor Vote for One Team State Offices Mathew (Matt) Kruse and Governor and Lieutenant Theresa Loeffler Governor Vote for One Team Jeff Johnson and Erin Murphy and Donna Bergstrom Erin Maye-Quade Tim Pawlenty and Lori Swanson and Michelle Fischbach Rick Nolan Attorney General Tim Walz and Vote for One Peggy Flanagan Doug Wardlow Tim Holden and James P.