Extracellular Spaces and Cardiac Conduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ION CHANNEL DIVERSITY and CHARACTERIZATION

ION CHANNEL DIVERSITY and CHARACTERIZATION Voltage clamp techniques K channels Na channels Ca channels Ligand-gated channels Channelopathies OUTLINE Voltage clamp techniques whole cell, single channel, gating K channels Na channels Ca channels Cardiac AP Na nerve vs cardiac Ica: L vs T type; drugs (BayK, nitrendipine) Ito: inactivation, subtypes Kv1.4, Kv4.2/3, accessory subunits Ikr,Iks, Ikur (drugs dofetilide) IK1 – rectification Cardiac channelopathies (LQTS, SQTS, Brugada syndrome) Ligand-gated channels (AChR) Pancreatic beta cell channels (KATP, ICa) Voltage clamp techniques Capacitance currents (Ic) and ionic currents (Ii) are activated by rapid changes in membrane potential using voltage clamp Variable Vtest can be applied with voltage clamp 2.0 sec 40 duration 20 (10 sec between each pulse) 0 -20 mV test -40 V -60 -80 Simplified schematic of voltage clamp circuit Original patch clamp recordings (1981) Pflugers Arch 391: 85-100 Four modes of patch clamp technique High-throughput, automated patch clamp instruments EVOLUTION and Ion channel diversity Diversity of ion channels Example: nematode C. elegans 73 K channels (20 6 TM, 3 IRK, 50 TWIK) 89 ligand-gated channels (42 ACh, 37 inhibitory GABAA or glutamate, 10 excitatory glutamate) 5 voltage-gated Ca channels 6 chloride channels 24 gap junction channels (connexins) 22 mechanosensitive channels 6 cyclic-nucleotide gated channels 11 TRP-related channels Total: 236 channel subunit genes Origin of ion channel diversity 1) gene duplication & divergence 2) alternative mRNA splicing 3) -

Src Regulation of Cx43 Phosphorylation and Gap Junction Turnover

biomolecules Article Src Regulation of Cx43 Phosphorylation and Gap Junction Turnover Joell L. Solan 1 and Paul D. Lampe 1,2,* 1 Translational Research Program, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA 98109, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Global Health, Pathobiology Program, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98109, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 October 2020; Accepted: 22 November 2020; Published: 24 November 2020 Abstract: The gap junction protein Connexin43 (Cx43) is highly regulated by phosphorylation at over a dozen sites by probably at least as many kinases. This Cx43 “kinome” plays an important role in gap junction assembly and turnover. We sought to gain a better understanding of the interrelationship of these phosphorylation events particularly related to src activation and Cx43 turnover. Using state-of-the-art live imaging methods, specific inhibitors and many phosphorylation-status specific antibodies, we found phospho-specific domains in gap junction plaques and show evidence that multiple pathways of disassembly exist and can be regulated at the cellular and subcellular level. We found Src activation promotes formation of connexisomes (internalized gap junctions) in a process involving ERK-mediated phosphorylation of S279/282. Proteasome inhibition dramatically and rapidly restored gap junctions in the presence of Src and led to dramatic changes in the Cx43 phospho-profile including to increased Y247, Y265, S279/282, S365, and S373 phosphorylation. Lysosomal inhibition, on the other hand, nearly eliminated phosphorylation on Y247 and Y265 and reduced S368 and S373 while increasing S279/282 phosphorylation levels. We present a model of gap junction disassembly where multiple modes of disassembly are regulated by phosphorylation and can have differential effects on cellular signaling. -

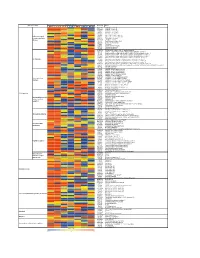

Supporting Figure 2

Normalized value Functional class Genbank Name Naive SC 1h SC 6h SC 24h WM 1h WM 6h WM 24h AB016161 GABA-B receptor 1d AF109405 GABA-B receptor 2a M35077 Dopamine-1A receptor S46131 Dopamine-1A receptor M84009 Dopamine receptor D4 U13368 Adrenergic receptor, alpha 1a G Protein-coupled M60654 Adrenergic receptor, alpha 1d receptors and their M64236 Tachykinin 1 receptor effectors AI229237 Opioid receptor-like Y11433 Pyrimidinergic receptor P2Y4 M64299 Adenosine A1 receptor E00001 Pro-insulin M29014 Insulin receptor precursor U35315 Serotonin receptor 2C S62043 Serotonin receptor 6 AF000368 Scn9a sodium channel, type IX, alpha polypeptide M27158 Kcna5 K+ voltage-gated channel, shaker-related subfamily, member 5 X17621 Kcna6 potassium voltage-gated channel, shaker-related, subfamily, member 6 X16476 Kcnb1 potassium voltage gated channel, Shab-related subfamily, member 1 M77482 Kcnb2 potassium voltage gated channel, Shab-related subfamily, member 2 S64320 Kcnd2 potassium voltage gated channel, Shal-related family, member 2 Ion channels X87635 Kcnj4 potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 4 D86039 Kcnj11 potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 11 X83581 Kcnj16 potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 16 AF073891 Kcnh5 potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag-related), member 5 U69882 Kcnn2 potassium intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated channel, subfamily N, member 2 Z36944 Chloride channel 4-2 Z56277 Chloride channel 5 L08493 GABA-A receptor alpha-4 subunit X51992 -

Ion Channels 3 1

r r r Cell Signalling Biology Michael J. Berridge Module 3 Ion Channels 3 1 Module 3 Ion Channels Synopsis Ion channels have two main signalling functions: either they can generate second messengers or they can function as effectors by responding to such messengers. Their role in signal generation is mainly centred on the Ca2 + signalling pathway, which has a large number of Ca2+ entry channels and internal Ca2+ release channels, both of which contribute to the generation of Ca2 + signals. Ion channels are also important effectors in that they mediate the action of different intracellular signalling pathways. There are a large number of K+ channels and many of these function in different + aspects of cell signalling. The voltage-dependent K (KV) channels regulate membrane potential and + excitability. The inward rectifier K (Kir) channel family has a number of important groups of channels + + such as the G protein-gated inward rectifier K (GIRK) channels and the ATP-sensitive K (KATP) + + channels. The two-pore domain K (K2P) channels are responsible for the large background K current. Some of the actions of Ca2 + are carried out by Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels and Ca2+-sensitive Cl − channels. The latter are members of a large group of chloride channels and transporters with multiple functions. There is a large family of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters some of which have a signalling role in that they extrude signalling components from the cell. One of the ABC transporters is the cystic − − fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) that conducts anions (Cl and HCO3 )and contributes to the osmotic gradient for the parallel flow of water in various transporting epithelia. -

An Update on Connexin Gap Junction and Hemichannels in Diabetic Retinopathy

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review An Update on Connexin Gap Junction and Hemichannels in Diabetic Retinopathy Jorge González-Casanova 1 , Oliver Schmachtenberg 2, Agustín D. Martínez 3, Helmuth A. Sanchez 3, Paloma A. Harcha 3 and Diana Rojas-Gomez 4,* 1 Instituto de Ciencias Biomédicas, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Santiago 8910060, Chile; [email protected] 2 Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencia de Valparaíso, Instituto de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso 2360102, Chile; [email protected] 3 Centro Interdisciplinario de Neurociencia de Valparaíso, Instituto de Neurociencia, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Valparaíso, Valparaíso 2360102, Chile; [email protected] (A.D.M.); [email protected] (H.A.S.); [email protected] (P.A.H.) 4 Escuela de Nutrición y Dietética, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Andres Bello, Santiago 8370146, Chile * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +56-2-26618559 Abstract: Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is one of the main causes of vision loss in the working age popu- lation. It is characterized by a progressive deterioration of the retinal microvasculature, caused by long-term metabolic alterations inherent to diabetes, leading to a progressive loss of retinal integrity and function. The mammalian retina presents an orderly layered structure that executes initial but complex visual processing and analysis. Gap junction channels (GJC) forming electrical synapses are present in each retinal layer and contribute to the communication between different cell types. Citation: González-Casanova, J.; In addition, connexin hemichannels (HCs) have emerged as relevant players that influence diverse Schmachtenberg, O.; Martínez, A.D.; physiological and pathological processes in the retina. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Effects of Neurosteroids, such as Pregnenolone Sulfate and its receptor, TrpM3 in the Retina. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04d8607f Author Webster, Corey Michael Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Effects of Neurosteroids, such as Pregnenolone Sulfate, and its receptor, TrpM3 in the Retina. By Corey Webster A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular and Cell Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Marla Feller, Chair Professor Diana Bautista Professor Daniella Kaufer Professor Stephan Lammel Fall 2019 The Effects of Neurosteroids, such as Pregnenolone Sulfate, and its receptor, TrpM3 in the Retina. Copyright 2019 by Corey Webster Abstract The Effects of Neurosteroids, such as Pregnenolone Sulfate, and its receptor, TrpM3 in the Retina. by Corey M. Webster Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular and Cell Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Marla Feller, Chair Pregnenolone sulfate (PregS) is the precursor to all steroid hormones and is produced in neurons in an activity dependent manner. Studies have shown that PregS production is upregulated during certain critical periods of development, such as in the first year of life in humans, during adolescence, and during pregnancy. Conversely, PregS is decreased during aging, as well as in several neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions. There are several known targets of PregS, such as a positive allosteric modulator NMDA receptors, sigma1 receptor, and as a negative allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors. -

Paxilline, a Closed BK Channel Blocker Expression Produces a 13-Mv Or 32-Mv Rightward Shift of Voltage Neces- Yu Zhou, Christopher J

Monday, March 7, 2011 261a In lymphocytes Ca2þ signals are essential for diverse cellular functions. After AT1 receptor, which will advance our understanding of GPCR-ion channel antigen binds to the T cell receptor a series of reactions are initiated that gen- interaction network on the fine regulation of vascular tone. Supported by 2þ erate IP3 and culminate in an increase in cytosolic Ca . Mechanisms that re- NIH. move Ca2þ also exert an important influence on the net Ca2þ level. The SERCA pump resequesters Ca2þ into the ER and the PMCA transports Ca2þ to the ex- þ 1429-Pos Board B339 tracellular side. Two key features of the PMCA are its stimulation by Ca2 -cal- Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase B Knockout Mice Have Impaired Activa- modulin and by PKA-dependent phosphorylation (Bers, 2001) but in most of tion of the Kþ channel KCa3.1 Resulting in Defective T Cell Activation the mathematical models this pump is represented with a simple Michaelis- þ Shekhar Srivastava, Lie Di, Olga Zhdanova, Yi Sun, Zhai Li, Menten formulation due to its small contribution to the overall Ca2 fluxes. Edward Y. Skolnik. This is not the case in T cells, Bautista et al (2002) showed that this pump is þ Nucleoside Diphosphate kinases (NDPK) are encoded by the Nme (non-met- the primary means of Ca2 extrusion in T cells and its activity is modulated þ þ astatic cell) gene family. While they comprise a family of 10 genes, NDPK-A by Ca2 enabling the cell to adapt to higher Ca2 values during T cell activa- 2þ and B are ubiquitously expressed and account for most of the NDPK- activ- tion. -

Aquaporin 0 Modulates Lens Gap Junctions in the Presence of Lens-Specific Beaded Filament Proteins

Lens Aquaporin 0 Modulates Lens Gap Junctions in the Presence of Lens-Specific Beaded Filament Proteins Sindhu Kumari,1 Junyuan Gao,1 Richard T. Mathias,1,2 Xiurong Sun,1 Amizhdini Eswaramoorthy,1 Nicholas Browne,1 Nigel Zhang,1 and Kulandaiappan Varadaraj1,2 1Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York, United States 2SUNY Eye Institute, Syracuse, New York, United States Correspondence: Kulandaiappan PURPOSE. The objective of this study was to understand the molecular and physiologic Varadaraj, Department of Physiology mechanisms behind the lens cataract differences in Aquaporin 0-knockout-Heterozygous and Biophysics, BST-6, Room # 165A, (AQP0-Htz) mice developed in C57 and FVB (lacks beaded filaments [BFs]) strains. School of Medicine, Stony Brook University, NY 11794-8661, USA; METHODS. Lens transparency was studied using dark field light microscopy. Water permeability kulandaiappan.varadaraj@ (Pf) was measured in fiber cell membrane vesicles. Western blotting/immunostaining was stonybrook.edu. performed to verify expression of BF proteins and connexins. Microelectrode-based intact Submitted: May 2, 2017 lens intracellular impedance was measured to determine gap junction (GJ) coupling Accepted: October 23, 2017 resistance. Lens intracellular hydrostatic pressure (HP) was determined using a microelec- trode/manometer system. Citation: Kumari S, Gao J, Mathias RT, et al. Aquaporin 0 modulates lens gap RESULTS. Lens opacity and spherical aberration were more distinct in AQP0-Htz lenses from junctions in the presence of lens- FVB than C57 strains. In either background, compared to wild type (WT), AQP0-Htz lenses specific beaded filament proteins. showed decreased Pf (approximately 50%), which was restored by transgenic expression of Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. -

Direct Immunogold Labeling of Aquaporin-4 in Square Arrays of Astrocyte and Ependymocyte Plasma Membranes in Rat Brain and Spinal Cord

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 95, pp. 11981–11986, September 1998 Neurobiology Direct immunogold labeling of aquaporin-4 in square arrays of astrocyte and ependymocyte plasma membranes in rat brain and spinal cord i JOHN E. RASH*†‡§,THOMAS YASUMURA*, C. SUE HUDSON*, PETER AGRE¶, AND SØREN NIELSEN *Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, †Program in Molecular, Cellular, and Integrative Neurosciences, and ‡Program in Cell and Molecular Biology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523; ¶Departments of Biological Chemistry and Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine; and iDepartment of Cell Biology, Institute of Anatomy, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark Communicated by Thomas S. Reese, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, August 13, 1998 (received for review March 1, 1998) ABSTRACT Aquaporin (AQP) water channels are abun- the glia limitans and that surround capillaries (3). AQP4 is dant in the brain and spinal cord, where AQP1 and AQP4 are especially abundant in astrocytes and ependymocytes in os- believed to play major roles in water metabolism and osmo- mosensory areas, including the supraoptic nucleus and sub- regulation. Immunocytochemical analysis of the brain re- fornical organ (3). These sites suggest a role for AQP4 in water cently revealed that AQP4 has a highly polarized distribution, transport between the brain parenchyma, cerebrospinal fluid, with marked expression in astrocyte end-feet that surround and blood, as well as a role in osmoregulation. capillaries and form the glia limitans; however, the structural Naturally occurring membranes enriched in AQP1 contain organization of AQP4 has remained unknown. In freeze- intramembrane particles (IMPs). Nevertheless, membrane re- fracture replicas, astrocyte end-feet contain abundant square constitution of AQP1 at high concentration yielded highly arrays of intramembrane particles that parallel the distribu- ordered two-dimensional crystalline lattices of AQP1, with a tion of AQP4. -

Functional Architecture of Inositol 1,4,5-Trisphosphate Signaling in Restricted Spaces of Myoendothelial Projections

Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections Jonathan Ledoux*, Mark S. Taylor†, Adrian D. Bonev*, Rachael M. Hannah*, Viktoriya Solodushko†, Bo Shui‡, Yvonne Tallini‡, Michael I. Kotlikoff‡, and Mark T. Nelson*§ *Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT 05405; †Department of Physiology, College of Medicine, University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL 36688; and ‡Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Edited by David E. Clapham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, and approved May 6, 2008 (received for review February 28, 2008) -Calcium (Ca2؉) release through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate recep- epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, and direct electrical communica tors (IP3Rs) regulates the function of virtually every mammalian tion via gap junctions (2, 3). Engagement of the EDHF cell. Unlike ryanodine receptors, which generate local Ca2؉ events functionality, regardless of its specific identity, depends on the (‘‘sparks’’) that transmit signals to the juxtaposed cell membrane, activation of calcium-sensitive, small-conductance (KCa2.3) a similar functional architecture has not been reported for IP3Rs. and intermediate-conductance (KCa3.1) potassium channels in .(Here, we have identified spatially fixed, local Ca2؉ release events the vascular endothelium (3 (‘‘pulsars’’) in vascular endothelial membrane domains that project Although Ca2ϩ waves and oscillations have been reported in through the internal elastic lamina to adjacent smooth muscle native endothelial preparations (4–6), organized patterns of 2؉ 2ϩ membranes. Ca pulsars are mediated by IP3Rs in the endothelial Ca signaling have not been identified, despite the unique endoplasmic reticulum of these membrane projections. -

Ryanodine Receptor of Skeletal Muscle Is a Gap Junction-Type Channel

Reprint Series 7 October 1988, Volume 242, pp. 99-102 Ryanodine Receptor of Skeletal Muscle Is a Gap Junction-Type Channel JIANJIE MA, MICHAEL FILL, C. MICHAEL KNUDSON, KEVIN P. CAMPBELL, AND ROBERTO CORONADO* Copyright © 1988 by the American Association for the Advancement of Science trolytes and nonelectrolytes and the fact that the open channels have several levels of conductance of large unit value (Fig. 1B) suggested a similarity to gap junctions. Channels formed by purified gap junction proteins have relatively large conductances that in physiological saline vary from 400 pS (2 nS in 1M KCl) in the bovine lens MIP-26 protein (9) to 140 and 280 pS in the rat liver 27 kD protein (10). Similar values have been reported in situ, in heart and lacrimal cells (11). In the case of the ryanodine receptor there appears to be at least three open states (Fig. 1B) with approximate conductances in 0.25M KCl of 800 pS, 400 pS (260 pS in 0.15M KCl), and 200 pS. The largest con- ductance (800 pS) is associated with the briefest lifetime (60 μs), whereas the lowest conductance (200 pS) is associated with the longest lifetime (8 ms). The 400-pS channel is most frequently observed and is thus the main contributor to the po. Thus, like junc- tional channel openings recorded with puri- Ryanodine Receptor of Skeletal Muscle Is a Gap fied proteins (9, 10), the ryanodine receptor has one or more conductance states that pass Junction–Type Channel large nonspecific currents. The strongest homology to junctional channels was found in the effects of protons, Ca2+ and 1-octanol, the well-known un- JIANJIE MA, MICHAEL FILL, C. -

Auxiliary Trafficking Subunit GJA1-20K Protects Connexin-43 from Degradation and Limits Ventricular Arrhythmias

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Journal of Clinical Investigation Auxiliary trafficking subunit GJA1-20k protects connexin-43 from degradation and limits ventricular arrhythmias Shaohua Xiao,1,2 Daisuke Shimura,1 Rachel Baum,1,3 Diana M. Hernandez,3 Sosse Agvanian,3 Yoshiko Nagaoka,3,4 Makoto Katsumata,3 Paul D. Lampe,5 Andre G. Kleber,6 TingTing Hong,1,3 and Robin M. Shaw1 1Nora Eccles Harrison Cardiovascular Research and Training Institute, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. 2Department of Neurology, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA. 3Department of Biomedical Sciences, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA. 4Department of Pathology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA. 5Translational Research Program, Public Health Sciences and Human Biology Divisions, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, Washington, USA. 6Department of Pathology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. Connexin-43 (Cx43) gap junctions provide intercellular coupling, which ensures rapid action potential propagation and synchronized heart contraction. Alterations in Cx43 localization and reductions in gap junction coupling occur in failing hearts, contributing to ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Recent reports have found that an internally translated Cx43 isoform, GJA1-20k, is an auxiliary subunit for the trafficking of Cx43 in heterologous expression systems. Here, we have created a mouse model by using CRISPR technology to mutate a single internal translation initiation site in Cx43 (M213L mutation), which generates full-length Cx43, but not GJA1-20k. We found that GJA1M213L/M213L mice had severely abnormal electrocardiograms despite preserved contractile function, reduced total Cx43, and reduced gap junctions, and they died suddenly at 2 to 4 weeks of age.