The Parable of the Trees and the Keeper of the Garden in the Thanksgiving Scroll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7

Chapter 20 4Q521 and What It Might Mean for Q 3–7 Gaye Strathearn am personally grateful for S. Kent Brown. He was a commit- I tee member for my master’s thesis, in which I examined 4Q521. Since that time he has been a wonderful colleague who has always encouraged me in my academic pursuits. The relationship between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian- ity has fueled the imagination of both scholar and layperson since their discovery in 1947. Were the early Christians aware of the com- munity at Qumran and their texts? Did these groups interact in any way? Was the Qumran community the source for nascent Chris- tianity, as some popular and scholarly sources have intimated,¹ or was it simply a parallel community? One Qumran fragment that 1. For an example from the popular press, see Richard N. Ostling, “Is Jesus in the Dead Sea Scrolls?” Time Magazine, 21 September 1992, 56–57. See also the claim that the scrolls are “the earliest Christian records” in the popular novel by Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 245. For examples from the academic arena, see André Dupont-Sommer, The Dead Sea Scrolls: A Preliminary Survey (New York: Mac- millan, 1952), 98–100; Robert Eisenman, James the Just in the Habakkuk Pesher (Leiden: Brill, 1986), 1–20; Barbara E. Thiering, The Gospels and Qumran: A New Hypothesis (Syd- ney: Theological Explorations, 1981), 3–11; Carsten P. Thiede, The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Jewish Origins of Christianity (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 152–81; José O’Callaghan, “Papiros neotestamentarios en la cueva 7 de Qumrān?,” Biblica 53/1 (1972): 91–100. -

The Angels Tarot for Ascension

The Angels Tarot 78 Different Angels to Awaken Your Inner Powers MEANING OF TAROT ROTA – TARO – ORAT – TORA – ATOR (The Wheel – Of Tarot – Speaks – The Law – Of Hator/ Nature) Karma: How We Manifest Our Reality Through Vibrations (Beliefs, Thoughts, Desires, Feelings, Actions) 78 Cards: 5 Elements • Spirit: 22 Major Arcana (Higher Consciousness) • 56 Minor Arcana (4 elemental suits): – Swords: Air (Mental) – Wands: Fire (Will) – Cups: Water (Emotional) – Coins: Earth (Material) (10 number and 4 courts each) Reading the Angels Tarot • Focus upon the Issues at Hand • Make an Intention to Receive Accurate Guidance and Healing • Meditation to Connect with Higher Self and Angelic Kingdom • Reverse half the deck and Shuffle gently to Randomize cards Layouts • Spread the Cards into an Arch on a Smooth Surface • Intuitively Pick the Cards and place them face down • Open Sequentially in Meditative State and Bring Each Angel In Angelic Healing and Meditation • Visualize the Angel on the card appearing before you • Ask the Angel to Guide you and Listen to the Answer through all Senses • Channelling the energy of the Angel for any of the Chakras or Aura, or into the Situation Reversed Cards • Fallen Angels or Dark Aspects of any Card to be Transformed • Blocked Energy of the Card to be Healed • Meditation with the Straightened Card to Understand and Accept the Lesson Major Arcana Spirit’s Journey from The Fool to The World For Ascension of Collective Consciousness The Fool ADAMAEL (Earth God) 0 of Spirit – Unknown Self Uranus and Rahu: Search for -

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons

Isaiah Commentaries & Sermons SONG OF SOLOMON JEREMIAH NEWEST ADDITIONS: Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 53 (Isaiah 52:13-53:12) - Bruce Hurt Verse by verse Commentary on Isaiah 35 - Bruce Hurt ISAIAH RESOURCES Commentaries, Sermons, Illustrations, Devotionals Click chart to enlarge Click chart to enlarge Chart from recommended resource Jensen's Survey of the OT - used by permission Another Isaiah Chart see on right side Caveat: Some of the commentaries below have "jettisoned" a literal approach to the interpretation of Scripture and have "replaced" Israel with the Church, effectively taking God's promises given to the literal nation of Israel and "transferring" them to the Church. Be a Berean Acts 17:11-note! ISAIAH ("Jehovah is Salvation") See Excellent Timeline for Isaiah - page 39 JEHOVAH'S JEHOVAH'S Judgment & Character Comfort & Redemption (Isaiah 1-39) (Isaiah 40-66) Uzziah Hezekiah's True Suffering Reigning Jotham Salvation & God Messiah Lord Ahaz Blessing 1-12 13-27 28-35 36-39 40-48 49-57 58-66 Prophecies Prophecies Warnings Historical Redemption Redemption Redemption Regarding Against & Promises Section Promised: Provided: Realized: Judah & the Nations Israel's Israel's Israel's Jerusalem Deliverance Deliverer Glorious Is 1:1-12:6 Future Prophetic Historic Messianic Holiness, Righteousness & Justice of Jehovah Grace, Compassion & Glory of Jehovah God's Government God's Grace "A throne" Is 6:1 "A Lamb" Is 53:7 Time 740-680BC OTHER BOOK CHARTS ON ISAIAH Interesting Facts About Isaiah Isaiah Chart The Book of Isaiah Isaiah Overview Chart by Charles Swindoll Visual Overview Introduction to Isaiah by Dr John MacArthur: Title, Author, Date, Background, Setting, Historical, Theological Themes, Interpretive Challenges, Outline by Chapter/Verse. -

A Tree in the Garden

MAIER BECKER A Tree in the Garden The Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge are one and the same tree. When the verse states ‘God caused to sprout the Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge’ (Gen. 2:9) it should be understood to mean, God caused to 1 sprout the Tree of Life which is also the Tree of Knowledge . R. J OSEPH KIMHI THIS COMMENT SEEMS to fly in the face of the basic details of the creation story in the Bible. In fact, it appears to contradict outright an explicit Biblical verse where God says “now (that man has eaten from the Tree of Knowledge), lest he partake from the Tree of Life as well” (3:22). 2 If the trees are one and the same, then by eating from the Tree of Knowledge man had already partaken of the Tree of Life! This essay proposes a reading of the Genesis story which provides a textual and conceptual basis for R. Kimhi’s explication, based on midrashic sources. I will suggest that R. Kimhi’s com - mentary sheds light on fundamental issues relating to man’s mortality and his relationship with God. 3 The Textual Starting Point The Bible introduces the Tree of Life stating; “God caused to sprout from the ground every tree that was pleasing to the sight and the Tree of Life betokh— within, the garden” (2:9). The text could have simply stated “the Tree of Life bagan —in the garden.” What does the word betokh , come to add? Onkelos translates the word betokh in this verse to mean bemitsiut— in the middle of the garden. -

The Jewish Symbols

UNIWERSYTET ZIELONOGÓRSKI Przegląd Narodowościowy – Review of Nationalities • Jews nr 6/2016 DOI: 10.1515/pn-2016-0014 ISSN 2084-848X (print) ISSN 2543-9391 (on-line) Krzysztof Łoziński✴ The Jewish symbols KEYWORDS: Jew, Judaism, symbol, archetype, Judaica SŁOWA KLUCZOWE: Żyd, judaizm, symbol, archetyp, judaica In every culture, people have always used symbols giving them sense and assigning them a specific meaning . Over the centuries, with the passage of time religious sym- bols have mingled with secular symbols . The charisms of Judaism have tuallymu in- termingled with the Christian ones taking on a new tribal or national form with in- fluences of their own culture . The aim of this article is to analyze and determine the influence of Judaic symbols on religious and social life of the Jews . The article indicates the sources of symbols from biblical times to the present day . I analyzed the symbols derived from Jewish culture, and those borrowed within the framework of acculturation with other communities as well . By showing examples of the interpenetration of cultures, the text is anattempt to present a wide range of meanings symbols: from the utilitarian, through religious, to national ones . It also describes their impact on the religious sphere, the influence on nurturing and preserving the national-ethnic traditions, sense of identity and state consciousness . The political value of a symbol as one of the elements of the genesisof the creation of the state of Israel is also discussed . “We live in a world of symbols, a world of symbols lives in us “ Jean Chevalier The world is full of symbols . -

The Nature of God and Christ Doctrinal Study Paper

United Church of God, an International Association .......... The Nature of God and Christ Doctrinal Study Paper Approved by the Council of Elders August 2005 All scriptures are quoted from The Holy Bible, New King James Version (© 1988 Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, Tennessee) unless otherwise noted. THE NATURE OF GOD AND CHRIST Doctrinal Study Paper Table of Contents Page Classical Trinitarian View of the Godhead 4 Question of Origins 5 Summary of Principal Views on the Origin of Christ 6 OLD TESTAMENT SECTION 6 The Tetragrammaton 6 The Shema and the “Oneness” of God 8 God (Elohim) in the Plural or Collective Sense 11 Anthropomorphic or Amorphical God 11 The God of the Old Testament 12 Theophanies 14 Angel of God’s Presence and YHWH 15 Who Was Married to Israel? 17 Who Led Israel to the Promised Land?—The 1 Corinthians 10:4 Question 19 NEW TESTAMENT SECTION 20 Neoplatonic, Gnostic and Jewish Concepts of the Logos 20 The Biblical Origin of the Logos 23 The Logos as the Agent of Creation 24 The Only Begotten Son of God 25 The Logos Empties Himself of Glory 26 The Logos Is Identified as Jesus Christ in Revelation 27 Christ’s Testimony of Glory He Shared With the Father 27 The Testimony of David Is Verified by Christ 28 Preexistence of Christ Confirmed by the Priesthood of Melchizedek 29 Christ’s Testimony of His Preexistence 31 Jesus Was Worshipped (Yet Only God Is to Be Worshipped) 32 The Testimony of Peter 32 God’s Purpose for Creating Humankind 33 Christ the Redeemer 34 God’s Purpose for Humanity 35 “One” (Greek Heis/Hen) God in the -

A N G E L S (Amemjam¿) 1

A N G E L S (amemJam¿) 1. Brief description 2. Nine orders of Angels 3. Archangels and Other Angels 1. Brief description of angels * Angels are spiritual beings created by God to serve Him, though created higher than man. Some, the good angels, have remained obedient to Him and carry out His will. Lucifer, whose ambitions were a distortion of God's plan, is known to us as the fallen angel, with the use of many names, among which are Satan, Belial, Beelzebub and the Devil. * The word "angelos" in Greek means messenger. Angels are purely spiritual beings that do God's will (Psalms 103:20, Matthew 26:53). * Angels were created before the world and man (Job 38:6,7) * Angels appear in the Bible from the beginning to the end, from the Book of Genesis to the Book of Revelation. * The Bible is our best source of knowledge about angels - for example, Psalms 91:11, Matthew 18:10 and Acts 12:15 indicate humans have guardian angels. The theological study of angels is known as angelology. * 34 books of Bible refer to angels, Christ taught their existence (Matt.8:10; 24:31; 26:53 etc.). * An angel can be in only one place at one time (Dan.9:21-23; 10:10-14), b. Although they are spirit beings, they can appear in the form of men (in dreams – Matt.1:20; in natural sight with human functions – Gen. 18:1-8; 22: 19:1; seen by some and not others – 2 Kings 6:15-17). * Angels cannot reproduce (Mark 12:25), 3. -

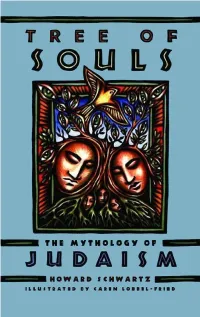

Tree of Souls: the Mythology of Judaism

96 MYTHS OF CREATION 124. THE PILLARS OF THE WORLD The world stands upon pillars. Some say it stands on twelve pillars, according to the number of the tribes of Israel. Others say that it rests on seven pillars, which stand on the water. This water is on top of the mountains, which rest on wind and storm. Still others say that the world stands on three pillars. Once every three hundred years they move slightly, causing earthquakes. But Rabbi Eleazar ben Shammua says that it rests on one pillar, whose name is “Righteous.” One of the ancient creation myths found in many cultures describes the earth as standing on one or more pillars. In this Jewish version of the myth, several theories are found—that the earth stands on twelve, seven, or three pillars—or on one. Rabbi Eleazar ben Shammua gives that one pillar the name of Tzaddik, “Righteous,” under- scoring an allegorical reading of this myth, whereby God is the pillar that supports the world. This, of course, is the central premise of monotheism. Alternatively, his comment may be understood to refer to the Tzaddik, the righteous man whose exist- ence is required for the world to continue to exist. Or it might refer to the principle of righteousness, and how the world could not exist without it. Sources: B. Hagigah 12b; Me’am Lo’ez on Genesis 1:10. 125. THE FOUNDATION STONE The world has a foundation stone. This stone serves as the starting point for all that was created, and serves as a true foundation. -

Isaiah 60 Through 66 and the New Testament (Compiled by Steve Gregg)

Isaiah 60 through 66 and the New Testament (compiled by Steve Gregg) Isaiah 60:3 Rev.21:24 The Gentiles shall come to your light, And the nations of those who are saved [a] shall walk in its And kings to the brightness of your rising. light, and the kings of the earth bring their glory and honor into it. Isaiah 60:5 Rev.21:26 The wealth of the Gentiles shall come to you. And they shall bring the glory and the honor of the nations into it. Isaiah 60:11 Rev.21:25 Therefore your gates shall be open continually; They Its gates shall not be shut at all by day (there shall be no shall not be shut day or night, night there). Isaiah 60:19 Rev.21:23 The sun shall no longer be your light by day, Nor for The city had no need of the sun or of the moon to shine in brightness shall the moon give light to you; But it, for the glory of God illuminated it. The Lamb is its light. the Lord will be to you an everlasting light, And your God your glory. Isaiah 60:21 Rev.21:27 Also your people shall all be righteous… But there shall by no means enter it anything that defiles, or causes an abomination or a lie… Isaiah 61:1-2 Luke 4:18-21 The Spirit of the Lord God is upon Me, because [Jesus quotes this passage and then says:] the Lord has anointed Me To preach good tidings to the “Today this Scripture is fulfilled in your hearing.” poor; He has sent Me to heal the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives, and the opening of the prison to those who are bound; to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord Isaiah 61:11 Mark 4:28 For as the earth brings forth its bud, as the garden causes For the earth yields crops by itself: first the blade, then the things that are sown in it to spring forth, so the the head, after that the full grain in the head. -

Isaiah 60:6 Scripture: Exodus 24 Herds of Camels Will Cover Your Land, Young Camels of Midian and Ephah

Daily Prayer Weekly Worship Bible Day 4: Isaiah 60:4 Reading Giving Time, Talents & "Lift up your eyes and look about you: All assemble and come to you; your sons come from afar, and your daughters are carried on the arm. Resources Spiritual Friendships Service In & Beyond the Church Along with the leading persons of the nations coming to Jerusalem, all those who had been forced to leave will also come. The sons and daughters are the children of those who were taken into captivity. Isaiah means that Jerusalem will be once again a place where others find January 5, 2020 inspiration and hope. Jerusalem is more than a physical city, it is a sign of hope. It is a place Day 1: Isaiah 60:1 where peace, justice and mercy are found. The concepts of justice and peace are fine ideas but "Arise, shine, for your light has come, and the glory of the LORD rises upon you. without a physical manifestation they do not on their own have the power to instill hope. With each new dawn we have new possibilities. The night is not a fearsome thing on its own. At night Question: Do you think the author is speaking figuratively or is this something he is because the world around us looks very different than in daytime. so that we can find the night seeing? Why? menacing. We feel better when we can see what is around us. In Isaiah’s time there were no street Challenge: What would for you be a physical manifestation of hope? lights. -

Arise, Shine to Put the Journey of the Wise Men in Perspective, Let Me Begin with a Line from This Morning’S First Lesson, from Isaiah 60

Pastor Gregory P. Fryer Immanuel Lutheran Church, New York, NY 1/6/2013, Epiphany Sunday Isaiah 60:1-6, Psalm 72:1-7, 10-14, Ephesians 3:1-12, Matthew 2:1-12 In the name of the Father and of the + Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen. 1Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of Herod the king, behold, wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, saying, 2“Where is he who has been born king of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the East, and have come to worship him.” (Matthew 2:1-2, RSV) God bless those Wise Men! The old saying is true, “Wise men still seeking him!” So do wise women, girls, and boys. One plain and good thing we can say about those Wise Men of old is that they were energetic. No slug-a-bed for them. The star of the new king shines in the East, and those Wise Men are off to seek this newborn king. No delay. No putting off till tomorrow the good they can begin today. Arise, shine To put the journey of the Wise Men in perspective, let me begin with a line from this morning’s First Lesson, from Isaiah 60. It speaks of light and of arousing oneself because of that light. The verse starts off this way: Arise, shine; for your light has come… (Isaiah 60:1, RSV) This text puts me in mind of those happy days of old, when Carol and I were young parents, when we would wake the children for the new day. -

The Book of the Watchers (Chapters 1–36)

The Book of the Watchers (Chapters 1–36) Superscription to the Book 1:1 The words of the blessing with which Enoch blessed the righteous chosen who will be present on the day of tribulation, to remove all the enemies; and the righteous will be saved. Introduction: An Oracle of Judgment (1:2—5:9) 2 And he took up his discoursea and said, “Enoch, a righteous man whose eyes were opened by God, who had the vision of the Holy One and of heaven, which he showed me. From the words of the watchers and holy ones I heard every- thing; and as I heard everything from them, I also understood what I saw. Not for this generation do I expound, but concerning one that is distant I speak. 3 And concerning the chosen I speak now, and concerning them I take up my discourse. The Theophany “The Great Holy One will come forth from his dwelling, 4 and the eternal God will tread from thence upon Mount Sinai. a Lit. parable (Aram matla<: Gk paraboleμ). 19 EEnochHermtrans.inddnochHermtrans.indd 1919 88/24/2012/24/2012 110:40:590:40:59 AMAM 20 1 Enoch 1:4-9 He will appear with his army,a he will appear with his mighty host from the heaven of heavens. 5 All the watchers will fear and <quake>,b and those who are hiding in all the ends of the earth will sing. All the ends of the earth will be shaken, and trembling and great fear will seize them (the watchers) unto the ends of the earth.