Tragopogon-Pratensis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Identifying Key Components of Interaction Networks Involving Greater Sage Grouse

Identifying Key Components of Interaction Networks Involving Greater Sage Grouse Sarah Barlow and Bruce Pavlik Conservation Department Red Butte Garden and Arboretum Salt Lake City, Utah 84105 Vegetation Forb seed Pollinators collections GSG Insects (chick diet) Chick Survivorship Linked to Vegetation Structure and Food Resource Abundance Gregg and Crawford 2009 J. Wildlife Man. 73:904-913 Astragalus geyeri Microsteris gracilis (Phacelia gracilis) https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/Microsteris_gracilis_1776.JPG/220px-Microsteris_gracilis_1776.JPG Agoseris heterophylla Achillea millefolium Taraxacum officinale Bransford, W.D. & Dophia http://www.americansouthwest.net/ Literature Survey: Forbs and Insects as Essential Foods Reference Field Site Insect Foods Forb Foods Achillea, Agoseris, Astragalus, Pennington et al. 2016 Review 41 invert taxa, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lactuca, Orthoptera Taraxacum, Trifolium, Lepidium Greg and Crawford 2009 NW Nevada Lepidoptera larvae especially strong Microsteris gracilis relation to SB "productive forbs" not at Thompson et al. 2006 Wyoming > 3<11 cm Hymenoptera, Ants, Coleoptera expense of sagebrush cover Drut, Crawford, Gregg 1994 Oregon Scarabs, Tenebrionids, ants w/ high occurrence Drut, Pyle and Crawford June beetles most preferred on all sites, Agoseris, Astragalus, Crepis, 1994 Oregon then Microsteris Tenebrionids and ants (by mass & freq) Trifolium (by mass & freq) Orthoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera (by Peterson 1970 Montana vol & freq) Taraxacum, Tragopogon, Lactuca (by -

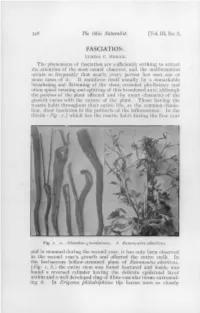

Fasciation. Lumina C

346 The Ohio Naturalist. [Vol. III, No. 3, FASCIATION. LUMINA C. RIDDLE. The phenomena of fasciation are sufficiently striking to attract the attention of the most casual observer, and the malformation occurs so frequently that nearly every person has seen one or more cases of it. It manifests itself usually by a remarkable broadening and flattening of the stem, crowded phyllotaxy and often spiral twisting and splitting of this broadened axis, although the portion of the plant affected and the exact character of the growth varies with the nature of the plant. Those having the rosette habit throughout their entire life, as the common dande- lion, show fasciation in the peduncle of the inflorescence. In the thistle (Fig. 2,) which has the rosette habit during the first year Fig. 1. a. Ailanthus glandulosus. b. Ranunculus abortivus, and is stemmed during the second year, it has only been observed in the second year's growth and affected the entire stalk. In the herbaceous hollow-stemmed plant of Ranunculus abortivus, {Fig. 1, b,) the entire stem was found fasciated and inside was found a reversed cylinder having the delicate epidermal layer within and a well developed ring of fibro-vascular tissue surround- ing it. In Erigeron philadelphicus the leaves were so closely Jan., 1903.] Fasciation. 347 compacted that the stem was entirely concealed while the top of the stalk was twisted down. In woody plants fasciated stems are nearly always split or twisted, often both, as shown in Ailanthus glandidosus {Fig. i, a.) Fasciation is found frequently occurring in man}- cultivated plants; the flowers, hyacinths, gladioli, narcissus, violets, gerani- u m s , nasturtiums ( Tropoeolum); the garden vegetables, cabbage or Brassica oleracea, and beets, Beta vulgaris ; and trees, Pinus, Thuya, Taxus, Salix, Alnus,Ulmus, Prunus and Populus. -

Rare Species As Examples of Plant Evolution G

Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs Volume 3 The Endangered Species: A Symposium Article 14 12-1-1979 Rare species as examples of plant evolution G. Ledyard Stebbins Department of Genetics, University of California, Davis, California 95616 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm Recommended Citation Stebbins, G. Ledyard (1979) "Rare species as examples of plant evolution," Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs: Vol. 3 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbnm/vol3/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RARE SPECIES AS EXAMPLES OF PLANT EVOLUTION G. Ledyaid Stebbins' .\bstract.- Rare species, including endangered ones, can be very valuable sources of information about evolution- arv processes. They may be rare and valuable because: (1) they are evolutionary youngsters and could represent an entirelv new evolutionary strategy of great scientific and practical value; (2) they are evolutionary relicts that have stored enormous amounts of genetic information of great worth; (3) they may represent endemic varieties that har- bor a great deal of the genetic variability in the gene pool that would be of enormous value to a plant geneticist; the rarity of the plant is not necessarily correlated with the size of its gene pool; (4) they may represent unique ecologi- cal adaptations of great value to future generations. Studies of gene pools and the genetics of adaptation constitute a new and developing field of the future. -

COVER CROPS and SOIL-BORNE FUNGI DANGEROUS TOWARDS the CULTIVATION of SALSIFY (Tragopogon Porrifolius Var

Acta Sci. Pol., Hortorum Cultus 10(2) 2011, 167-181 COVER CROPS AND SOIL-BORNE FUNGI DANGEROUS TOWARDS THE CULTIVATION OF SALSIFY (Tragopogon porrifolius var. sativus (Gaterau) Br.) Elbieta Patkowska, Mirosaw Konopiski University of Life Sciences in Lublin Abstract. Salsify has a remarkable taste and nutritious values. It is a rich source of inulin – a glycoside which has a positive effect on human and animal organisms. The paper pre- sents studies on the species composition of soil-borne fungi infecting the roots of Tragopogon porrifolius var. sativus cultivated with the use of oats, tansy phacelia and spring vetch as cover crops. In a field experiment the cover crops formed abundant green mass before winter and it constituted a natural mulch on the surface of the plough land. It was managed in two ways: 1) mixed with the soil as a result of spring ploughing, or 2) mixed with the soil as a result of pre-winter ploughing. The conventional cultivation of salsify, i.e. without cover crops, constituted the control. The studies established the number and health status of four-week-old salsify seedlings and roots with necrotic signs. A laboratory mycological analysis made it possible to determine the quantitative and qualitative composition of fungi infecting the underground parts of Tragopogon porri- folius var. sativus. The emergences and the proportion of infected salsify seedlings varied and depended on the species of the mulching plant. The smallest number of infected seed- lings was obtained after the mulch with oats, slightly more after the application of spring vetch or tansy phacelia as cover crops, and the most in the control. -

Inf.9 Proposal from Germany

INF.9 PROPOSAL FROM GERMANY This proposal reflects the wish of delegates expressed during the 56 th session of the Specialized Section: – to elaborate a standard for root vegetables other than carrots, – to include the tubercle vegetables. The intention of this standard for root and tubercle vegetables is, to integrate the existing UNECE standards for scorzonera (FFV-33), horse-radish (FFV-20), and radishes (FFV-43). Thus, while approving this draft standard as new UNECE standard, these standards should be withdrawn. UNECE STANDARD FFV-No concerning the marketing and commercial quality control of ROOT AND TUBERCLE VEGETABLES 1 I. DEFINITION OF PRODUCE This standard applies to root and tubercle vegetables of varieties (cultivars) grown from the following species to be supplied fresh to the consumer, root and tubercle vegetables for industrial processing being excluded: – beet tubercle ( Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris var. vulgaris und var. lutea DC.), – celeriac ( Apium graveolens L. var. rapaceum (Mill.) Gaudin), – Hamburg parsley ( Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Nyman ex A. W. Hill var. tuberosum (Bernh.) Mart Crov.), – horse-radish ( Armoracia rusticana Gottfr. Gaertn., B. Mey. et Scherb.), – kohlrabi, cabbage turnip (Brassica olearacea var. gongylodes L.) – parsnips ( Pastinaca sativa L.), – radishes ( Raphanus sativus L. var. sativus ), – radishes ( Raphanus sativus var. niger (Mill.) J. Kern.). – salsify ( Tragopogon porrifolius L. ssp. porrifolius ), – scorzonera ( Scorzonera hispanica L.), – swede ( Brassica napus L. (Napobrassica-group)), – turnips ( Brassica rapa L. (Rapa-group)), – turnip-rooted chervil or bulbous chervil ( Chaerophyllum bulbosum L.), – root and tubercle vegetables of other species and any hybrids. II. PROVISIONS CONCERNING QUALITY 1 Note: For carrots ( Daucus carota L.) the UNECE standard FFV-10 applies. -

The Vascular Flora of Rarău Massif (Eastern Carpathians, Romania). Note Ii

Memoirs of the Scientific Sections of the Romanian Academy Tome XXXVI, 2013 BIOLOGY THE VASCULAR FLORA OF RARĂU MASSIF (EASTERN CARPATHIANS, ROMANIA). NOTE II ADRIAN OPREA1 and CULIŢĂ SÎRBU2 1 “Anastasie Fătu” Botanical Garden, Str. Dumbrava Roşie, nr. 7-9, 700522–Iaşi, Romania 2 University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Iaşi, Faculty of Agriculture, Str. Mihail Sadoveanu, nr. 3, 700490–Iaşi, Romania Corresponding author: [email protected] This second part of the paper about the vascular flora of Rarău Massif listed approximately half of the whole number of the species registered by the authors in their field trips or already included in literature on the same area. Other taxa have been added to the initial list of plants, so that, the total number of taxa registered by the authors in Rarău Massif amount to 1443 taxa (1133 species and 310 subspecies, varieties and forms). There was signaled out the alien taxa on the surveyed area (18 species) and those dubious presence of some taxa for the same area (17 species). Also, there were listed all the vascular plants, protected by various laws or regulations, both internal or international, existing in Rarău (i.e. 189 taxa). Finally, there has been assessed the degree of wild flora conservation, using several indicators introduced in literature by Nowak, as they are: conservation indicator (C), threat conservation indicator) (CK), sozophytisation indicator (W), and conservation effectiveness indicator (E). Key words: Vascular flora, Rarău Massif, Romania, conservation indicators. 1. INTRODUCTION A comprehensive analysis of Rarău flora, in terms of plant diversity, taxonomic structure, biological, ecological and phytogeographic characteristics, as well as in terms of the richness in endemics, relict or threatened plant species was published in our previous note (see Oprea & Sîrbu 2012). -

Flora Mediterranea 26

FLORA MEDITERRANEA 26 Published under the auspices of OPTIMA by the Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum Palermo – 2016 FLORA MEDITERRANEA Edited on behalf of the International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo by Francesco M. Raimondo, Werner Greuter & Gianniantonio Domina Editorial board G. Domina (Palermo), F. Garbari (Pisa), W. Greuter (Berlin), S. L. Jury (Reading), G. Kamari (Patras), P. Mazzola (Palermo), S. Pignatti (Roma), F. M. Raimondo (Palermo), C. Salmeri (Palermo), B. Valdés (Sevilla), G. Venturella (Palermo). Advisory Committee P. V. Arrigoni (Firenze) P. Küpfer (Neuchatel) H. M. Burdet (Genève) J. Mathez (Montpellier) A. Carapezza (Palermo) G. Moggi (Firenze) C. D. K. Cook (Zurich) E. Nardi (Firenze) R. Courtecuisse (Lille) P. L. Nimis (Trieste) V. Demoulin (Liège) D. Phitos (Patras) F. Ehrendorfer (Wien) L. Poldini (Trieste) M. Erben (Munchen) R. M. Ros Espín (Murcia) G. Giaccone (Catania) A. Strid (Copenhagen) V. H. Heywood (Reading) B. Zimmer (Berlin) Editorial Office Editorial assistance: A. M. Mannino Editorial secretariat: V. Spadaro & P. Campisi Layout & Tecnical editing: E. Di Gristina & F. La Sorte Design: V. Magro & L. C. Raimondo Redazione di "Flora Mediterranea" Herbarium Mediterraneum Panormitanum, Università di Palermo Via Lincoln, 2 I-90133 Palermo, Italy [email protected] Printed by Luxograph s.r.l., Piazza Bartolomeo da Messina, 2/E - Palermo Registration at Tribunale di Palermo, no. 27 of 12 July 1991 ISSN: 1120-4052 printed, 2240-4538 online DOI: 10.7320/FlMedit26.001 Copyright © by International Foundation pro Herbario Mediterraneo, Palermo Contents V. Hugonnot & L. Chavoutier: A modern record of one of the rarest European mosses, Ptychomitrium incurvum (Ptychomitriaceae), in Eastern Pyrenees, France . 5 P. Chène, M. -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

Western Salsify in Range, Pasture, and CRP

Western Salsify in Range, Pasture, and CRP Jane Mangold 2010 Pest Management Tour Outline . Identification . Life history/Biology . Ecology . Management . Research trial Western Salsify (Tragopogon dubius) . Also known as goat’s-beard, oyster plant . “Salsify” = “a plant that follows the sun” Do you have western salsify on your land? 1. Yes 2. No 3. Not sure 0% 0% 0% Yes No Not sure 0 of 5 Has western salsify been increasing over the past several years on your land? 1. Yes 2. No 3. Not sure 0% 0% 0% Yes No Not sure 0 of 5 For those of you who DO have western salsify, do you consider it a problem? 1. Yes 2. No 3. Not sure 0% 0% 0% Yes No Not sure 0 of 5 On my land, western salsify is a problem mainly on 1. Cropland 2. CRP 3. Range/pasture 0% 0% 0% Cropland CRP Range/pasture 0 of 5 IDENTIFICATION . Linear, grass-like leaves • Rubbery, smooth to touch . Leaves clasp stem at base . Milky juice . Hollow stem below flower . Yellow, dandelion-like flower . Bracts extend beyond flower . Fluffy, sphere of seeds . Seeds with umbrella-like pappus Tragopogon Species . T. dubius • Western salsify, western goat’s-beard . T. pratensis • Meadow salsify, meadow goat’s-beard, Jack-go-to- bed-at-noon . T. porrifolius • Common salsify, garden salsify, oyster-plant . T. miscellus • Hybrid of T. dubius and T. pratensis . T. mirus • Hybrid of T. dubius and T. porrifolius Tragopogon Distributions T. dubius T. pratensis T. porrifolius T. miscellus T. mirus Flower Comparisons T. dubius—yellow, long bracts T. -

Yellow Salsify Tragopogon Dubius Scop

yellow salsify Tragopogon dubius Scop. Synonyms: Tragopogon dubius Scop. ssp. major (Jacq.) Voll., Tragopogon major Jacq. Other common name: common salsify, goat’s beard, goatsbeard, meadow goat’s beard, salsifis majeur, salsify, western goat’s beard, western salsify, wild oysterplant, yellow goat’s beard Family: Asteraceae Invasiveness Rank: 50 The invasiveness rank is calculated based on a species’ ecological impacts, biological attributes, distribution, and response to control measures. The ranks are scaled from 0 to 100, with 0 representing a plant that poses no threat to native ecosystems and 100 representing a plant that poses a major threat to native ecosystems. Description could be confused with yellow salsify. It grows Yellow salsify is biennial plant that grows 30 ½ to 91 throughout Canada. Unlike yellow salsify, meadow cm tall from a large taproot. All parts of the plant salsify does not have swollen stems below the flower contain a milky, white juice. Leaves are up to 30 ½ cm heads, and each of its flowers has only 8 or 9 floral long, clasping, alternate, narrow, grass-like, somewhat bracts (Royer and Dickinson 1999). No other tall, fleshy, hairless, and light-green to blue-green. Flower yellow-flowered Asteraceae species in Alaska have heads are 2 ½ to 6 ¼ cm across with yellow ray flowers. milky juice and long, narrow bracts. Flower heads form at the end of long, hollow peduncles. There are 10 to 14 bracts subtending each head. Bracts are 2 ½ to 5 cm long and extend beyond the ray flowers. Leaves from the previous year are often found at the base of the plant. -

Plants of Hot Springs Valley and Grover Hot Springs State Park Alpine County, California

Plants of Hot Springs Valley and Grover Hot Springs State Park Alpine County, California Compiled by Tim Messick and Ellen Dean This is a checklist of vascular plants that occur in Hot Springs Valley, including most of Grover Hot Springs State Park, in Alpine County, California. Approximately 310 taxa (distinct species, subspecies, and varieties) have been found in this area. How to Use this List Plants are listed alphabetically, by family, within major groups, according to their scientific names. This is standard practice for plant lists, but isn’t the most user-friendly for people who haven’t made a study of plant taxonomy. Identifying species in some of the larger families (e.g. the Sunflowers, Grasses, and Sedges) can become very technical, requiring examination of many plant characteristics under high magnification. But not to despair—many genera and even species of plants in this list become easy to recognize in the field with only a modest level of study or help from knowledgeable friends. Persistence will be rewarded with wonder at the diversity of plant life around us. Those wishing to pursue plant identification a bit further are encouraged to explore books on plants of the Sierra Nevada, and visit CalPhotos (calphotos.berkeley.edu), the Jepson eFlora (ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora), and CalFlora (www.calflora.org). The California Native Plant Society (www.cnps.org) promotes conservation of plants and their habitats throughout California and is a great resource for learning and for connecting with other native plant enthusiasts. The Nevada Native Plant Society nvnps.org( ) provides a similar focus on native plants of Nevada.