Terrorists, Geopolitics and Kenya's Proposed Border Wall with Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mandera County Hiv and Aids Strategic Plan 2016-2019

MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” i MANDERA COUNTY HIV AND AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN 2016-2019 “A healthy and productive population” Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used for commercial purposes or for profit. iv MANDERA COUNTY HIV & AIDS STRATEGIC PLAN (2016- 2019) Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations vii Foreword viii Preface ix Acknowledgement x CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Information xii 1.2 Demographic characteristics 2 1.3 Land availability and use 2 1.3 Purpose of the HIV Plan 1.4 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 1.5 Guiding principles CHAPTER TWO: HIV STATUS IN THE COUNTY 2.1 County HIV Profiles 5 2.2 Priority population 6 2.3 Gaps and challenges analysis 6 CHAPTER THREE: PURPOSE OF Mcasp, strateGIC PLAN DEVELOPMENT process AND THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES 8 3.1 Purpose of the HIV Plan 9 3.2 Process of developing the HIV and AIDS Strategic Plan 9 3.3 Guiding principles 9 CHAPTER FOUR: VISION, GOALS, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 10 4.1 The vision, goals and objectives of the county 11 4.2 Strategic directions 12 4.2.1 Strategic direction 1: Reducing new HIV infection 12 4.2.2 Strategic direction 2: Improving health outcomes and wellness of people living with HIV and AIDS 14 4.2.3 Strategic Direction 3: Using human rights based approach1 to facilitate access to services 16 4.2.4 Strategic direction 4: Strengthening Integration of community and health systems 18 4.2.5 Strategic Direction 5: Strengthen Research innovation and information management to meet the Mandera County HIV Strategy goals. -

Taming the Intractable Inter-Ethnic Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle

International Journal of Innovative Research and Knowledge Volume-3 Issue-7, July-2018 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE ISSN-2213-1356 www.ijirk.com TAMING THE INTRACTABLE INTER-ETHNIC CONFLICT IN THE ILEMI TRIANGLE PETERLINUS OUMA ODOTE, PHD Abstract This article provides an overview of the historical trends of conflict in the Ilemi triangle, exploring the issues, the nature, context and dynamics of these conflicts. The author endeavours to deepen the understanding of the trends of conflict. A consideration on the discourse on the historical development is given attention. The article’s core is conflict between the five ethnic communities that straddle this disputed triangle namely: the Didinga and Toposa from South Sudan; the Nyangatom, who move around South Sudan and Ethiopia; the Dassenach, who have settled East of the Triangle in Ethiopia; and the Turkana in Kenya. The article delineates different factors that promote conflict in this triangle and how these have impacted on pastoralism as a way of livelihood for the five communities. Lastly, the article discusses the possible ways to deal with the intractable conflict in the Ilemi Triangle. Introduction Ilemi triangle is an arid hilly terrain bordering Kenya, South Sudan and Ethiopia, that has hit the headlines and catapulted onto the international centre stage for the wrong reasons in the recent past. Retrospectively, the three countries have been harshly criticized for failure to contain conflict among ethnic communities that straddle this contested area. Perhaps there is no better place that depicts the opinion that the strong do what they will and the weak suffer what they must than the Ilemi does. -

Usaid Kenya Niwajibu Wetu (Niwetu) Fy 2018 Q3 Progress Report

USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT JULY 2018 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI Global, LLC. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 1 USAID KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) FY 2018 Q3 PROGRESS REPORT 1 April – 30 June 2018 Award No: AID-OAA-I-13-00013/AID-615-TO-16-00010 Prepared for John Langlois United States Agency for International Development/Kenya C/O American Embassy United Nations Avenue, Gigiri P.O. Box 629, Village Market 00621 Nairobi, Kenya Prepared by DAI Global, LLC 4th Floor, Mara 2 Building Eldama Park Nairobi, Kenya DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. USAID/KENYA NIWAJIBU WETU (NIWETU) PROGRESS REPORT FOR Q3 FY 2018 2 CONTENTS I. NIWETU EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................... vii II. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS (Qualitative Impact) ................................................................ 9 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (Quantitative Impact) .......................................................... 20 III. ACTIVITY PROGRESS (QUANTITATIVE IMPACT) ............................................... 20 IV. CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES ................................................................. 39 V. PERFORMANCE MONITORING ............................................................................... -

South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan

South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan Final Report September 2012 This publication was produced by Nathan Associates Inc. for review by the United States Agency for International Development under the USAID Worldwide Trade Capacity Building (TCBoost) Project. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. South Sudan Corridor Diagnostic Study and Action Plan Final Report SUBMITTED UNDER Contract No. EEM-I-00-07-00009-00, Order No. 2 SUBMITTED TO Mark Sorensen USAID/South Sudan Cory O’Hara USAID EGAT/EG Office SUBMITTED BY Nathan Associates Inc 2101 Wilson Boulevard, Suite 1200 Arlington, Virginia 22201 703.516.7700 [email protected] [email protected] DISCLAIMER This document is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Its contents are the sole responsibility of the author or authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Acronyms v Executive Summary vii 1. Introduction 1 Study Scope 1 Report Organization 3 2. Corridor Infrastructure 5 South Sudan Corridor Existing Infrastructure and Condition 5 3. Corridor Performance 19 Performance Data: Nodes and Links 19 Overview of South Sudan Corridor Performance 25 South Sudan Corridor Cost and Time Composition 26 Interpretation of Results for South Sudan Corridor 29 4. Legal and Regulatory Framework 33 Overview of Legal System 33 National Transport Policy 36 Transport Legal and Regulatory Framework Analysis 40 Customs and Taxation: Legal and Regulatory Framework Analysis 53 5. -

Delimitation of the Elastic Ilemi Triangle: Pastoral Conflicts and Official Indifference in the Horn of Africa

Delimitation Of The Elastic Ilemi Triangle: Pastoral Conflicts and Official Indifference in the Horn Of Africa NENE MBURU ABSTRACT This article observes that although scholars have addressed the problem of the inherited colonial boundaries in Africa, there are lacunae in our knowledge of the complexity of demarcating the Kenya-Sudan-Ethiopia tri-junctional point known as the Ilemi Triangle. Apart from being a gateway to an area of Sudan rich in unexplored oil reserves, Ilemi is only significant for its dry season pastures that support communities of different countries. By analyzing why, until recently, the Ilemi has been ‘unwanted’ and hence not economically developed by any regional government, the article aims to historically elucidate differences of perception and significance of the area between the authorities and the local herders. On the one hand, the forage-rich pastures of Ilemi have been the casus belli (cause for war) among transhumant communities of Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya, and an enigma to colonial surveyors who could not determine their ‘ownership’ and extent. On the other hand, failure to administer the region in the last century reflects the lack of attractiveness to the authorities that have not agreed on security and grazing arrangements for the benefit of their respective nomadic populations. This article places the disputed ‘triangle’ of conflict into historical, anthropological, sociological and political context. The closing reflections assess the future of the dispute in view of the current initiative by the USA to end the 19-year-old civil war in Sudan and promote the country’s relationship with her neighbors particularly Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia. -

P0249-P0262.Pdf

THE CONDOR VOLUME 57 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER. 19.55 NUMBER 5 A SYSTEMATIC REVISION AND NATURAL HISTORY OF THE SHINING SUNBIRD OF AFRICA By JOHN G. WILLIAMS The ,Shining Sunbird (Cinnyris habessinicus Hemprich and Ehrenberg) has a com- paratively restricted distribution in the northeastern part of the Ethiopian region. It occurs sporadically from the northern districts of Kenya Colony and northeastern Uganda northward to Saudi Arabia, but it apparently is absent from the highlands of Ethiopia (Abyssinia) above 5000 feet. The adult male is one of the most brightly col- ored African sunbirds, the upper parts and throat being brilliant metallic green, often with a golden sheen on the mantle, and the crown violet or blue. Across the breast is a bright red band, varying in width, depth of color, and brilliance in the various races, bordered on each side by yellow pectoral tufts; the abdomen is black. The female is drab gray or brown and exhibits a well-marked color cline, the most southerly birds being pale and those to the northward becoming gradually darker and terminating with the blackish-brown female of the most northerly subspecies. In the present study I am retaining, with some reluctance, the genus Cinnyris for the speciesunder review. I agree in the main with Delacour’s treatment of the group in his paper ( 1944) “A Review of the Family Nectariniidae (Sunbirds) ” and admit that the genus Nectarinia, in its old, restricted sense, based upon the length of the central pair of rectrices in the adult male, is derived from a number of different stocks and is ur+ sound. -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

Project Information Document (Pid) Concept Stage

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) CONCEPT STAGE Report No.: PIDC446 Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name South Sudan- Eastern Africa Regional Transport , Trade and Development Facilitation Program (Phase One) (P131426) Region AFRICA Public Disclosure Copy Country Africa Sector(s) Rural and Inter-Urban Roads and Highways (60%), Public administration- Transportation (20%), General industry and trade sector (20%) Theme(s) Trade facilitation and market access (70%), Regional integration (30%) Lending Instrument Investment Project Financing Project ID P131426 Borrower(s) Ministry of Finance, Commerce and Economic Planning, Ministry of Public Disclosure Authorized Finance Implementing Agency Ministry of Transport, Roads and Bridges, Ministry of Transport and Infrastructure Environmental B-Partial Assessment Category Date PID Prepared/ 29-Aug-2013 Updated Date PID Approved/ 03-Sep-2013 Disclosed Estimated Date of 30-Sep-2013 Appraisal Completion Public Disclosure Authorized Estimated Date of 30-Jan-2014 Board Approval Concept Review Track II - The review did authorize the preparation to continue Public Disclosure Copy Decision I. Introduction and Context Country Context Deepening regional integration – economic opportunity for South Sudan & neighbors 1. The countries in the Eastern Africa sub-region, including Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Ethiopia, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and South Sudan recorded an average annual economic growth rate of about 5 percent over the last decade. The sub- Public Disclosure Authorized -

Land and Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle of East Africa

Land and Conflict in the Ilemi Triangle of East Africa By Maurice N. Amutabi Abstract Insecurity among the nations of the Horn of Africa is often concentrated in the nomadic pastoralist areas. Why? Is the pastoralist economy, which revolves around livestock, raiding and counter-raiding to blame for the violence? Why are rebel movements in the Horn, such the Lord‟s Resistance Army (LRA) in Uganda, the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) in Ethiopia, several warlords in Somalia, etc, situated in nomadic pastoralist areas? Is the nomadic lifestyle to blame for lack of commitment to the ideals of any one nation? Why have the countries in the Horn failed to absorb and incorporate nomadic pastoralists in their structures and institutions, forty years after independence? Utilizing a political economy approach, this article seeks to answer these questions, and more. This article is both a historical and philosophical interrogation of questions of nationhood and nationalism vis-à-vis the transient or mobile nature that these nomadic pastoralist “nations” apparently represent. It scrutinizes the absence of physical and emotional belonging and attachment that is often displayed by these peoples through their actions, often seen as unpatriotic, such as raiding, banditry, rustling and killing for cattle. The article assesses the place of transient and migratory ethnic groups in the nation-state, especially their lack of fixed abodes in any one nation-state and how this plays out in the countries of the region. I pay special attention to cross-border migratory ethnic groups that inhabit the semi-desert areas of the Sudan- Kenya-Ethiopia-Somalia borderlines as case studies. -

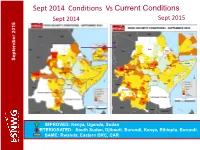

FSNWG Presentation

Sept 2014 Conditions Vs Current Conditions Sept 2015 Sept 2014 September 2015 September September September 2015 IMPROVED: Kenya, Uganda, Sudan DETERIORATED: South Sudan, Djibouti, Burundi, Kenya, Ethiopia, Burundi. SAME: Rwanda, Eastern DRC, CAR Current Conditions: Regional Highlights • Crisis and emergency food insecurity remains a concern in parts of DRC, CAR, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya, parts of Karamoja, Darfur in Sudan, IDP sites in Somalia; September 2015 September • An estimated 17.9 people may be facing food insecurity in the region. • Dry conditions in pastoral areas of Ethiopia, Djibouti and Sudan are expected to continue till Dec (GHACOF, Aug.). • Conflicts/political tension remains a key driver for food insecurity in the region (e.g South Sudan, Burundi, CAR, eastern DRC and Somalia. • El Nino expected to lead to above average rainfall in some areas leading to improved food security outcomes but also localised flooding but depressed rainfalls in others persisting stressed/ food insecurity conditions General improvement in food security situation in the region. However, some deterioration seen in pastoral areas and an estimated 17.9M people in need of humanitarian assistance. Current Conditions – Burundi Burundi WFP, IPC (priliminary) •Generally food security conditions is good due to the season B harvest. September 2015 September •About 100,000 are considered in food insecurity crisis. •Significant number of farming population have fled to neigboring countries (UNHCR) due to the political crisis •The political crisis negatively affected Economic Activities in the country, particularly the capital Bujumbura. Trade in agricultural comoditities fell by about 50%. •The lean period is expected to start in September, is likely be exacerbated by the negative effects of the current crisis Food security relatively stable due to Season B production though expected to remain stressed to December. -

Abstracts 2019 July Graduation

ABSTRACTS 2019 JULY GRADUATION PHD SCHOOL OF BUSINESS FINANCING DECISIONS AND SHAREHOLDER VALUE CREATIONOF NON- FINANCIAL FIRMS QUOTED AT THE NAIROBI SECURITIES EXCHANGE, KENYA KARIUKI G MUTHONI-PHD Department: Business Administration Supervisors: Dr. Ambrose O. Jagongo Dr. Joseph Muniu Shareholder value creation and profit maximizing are among the primary objectives of a firm. Shareholder value creation focuses more on long term sustainability of returns and not just profitability. Rational investors expect good long term yield of their investment. Corporate financial decisions play an imperative role in general performance of a company and shareholder value creation. There have been a number of firms facing financial crisis among them; Mumias Sugar Ltd, Uchumi Supermarkets Ltd and Kenya Airways Ltd. All these companies are quoted at the Nairobi Securities Exchange. Due to declining performance of these companies, share prices have been dropping and shareholders do not receive dividends. This study investigated the effects of financing decisions on shareholder value creation of non- financial firms quoted at NSE for the period 2008-2014. The study was guided by various finance models; which include, Modigliani and Miller, Pecking Order Theory, Agency Free Flow Theory, Market Timing Theory and Capital Asset Pricing Model. The study used general and empirical models from previous studies as a basis for studying specific models which were modified to suit the current study. The study was guided by the positivism philosophy. The study employed explanatory design which is non-experimental. Census design was used as the number of non- financial firms at the time of the study was 40 companies. The data was gathered from NSE handbooks and CMA publications comprising of annual financial statements, income statements and accompanying notes. -

INSULT to INJURY the 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’S Abusive Response

INSULT TO INJURY The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH hrw.org www.khrc.or.ke Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-32446 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2015 978-1-6231-32446 Insult to Injury The 2014 Lamu and Tana River Attacks and Kenya’s Abusive Response Map of Kenya and Coast Region ........................................................................................ i Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ..........................................................................................................