Macartney's Things. Were They Useful? Knowledge and the Trade To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annie Ross Uk £3.25

ISSUE 162 SUMMER 2020 ANNIE ROSS UK £3.25 Photo by Merlin Daleman CONTENTS Photo by Merlin Daleman ANNIE ROSS (1930-2020) The great British-born jazz singer remembered by VAL WISEMAN and DIGBY FAIRWEATHER (pages 12-13) THE 36TH BIRMINGHAM, SANDWELL 4 NEWS & WESTSIDE JAZZ FESTIVAL Birmingham Festival/TJCUK OCTOBER 16TH TO 25TH 2020 7 WHAT I DID IN LOCKDOWN [POSTPONED FROM ORIGINAL JULY DATES] Musicians, promoters, writers 14 ED AND ELVIN JAZZ · BLUES · BEBOP · SWING Bicknell remembers Jones AND MORE 16 SETTING THE STANDARD CALLUM AU on his recent album LIVE AND ROCKING 18 60-PLUS YEARS OF JAZZ MORE THAN 90% FREE ADMISSION BRIAN DEE looks back 20 THE V-DISC STORY Told by SCOTT YANOW 22 THE LAST WHOOPEE! Celebrating the last of the comedy jazz bands 24 IT’S TRAD, GRANDAD! ANDREW LIDDLE on the Bible of Trad FIND US ON FACEBOOK 26 I GET A KICK... The Jazz Rag now has its own Facebook page. with PAOLO FORNARA of the Jim Dandies For news of upcoming festivals, gigs and releases, features from the archives, competitions and who 26 REVIEWS knows what else, be sure to ‘like’ us. To find the Live/digital/ CDs page, simply enter ‘The Jazz Rag’ in the search bar at the top when logged into Facebook. For more information and to join our mailing list, visit: THE JAZZ RAG PO BOX 944, Birmingham, B16 8UT, England UPFRONT Tel: 0121454 7020 BRITISH JAZZ AWARDS CANCELLED WWW.BIRMINGHAMJAZZFESTIVAL.COM Fax: 0121 454 9996 Email: [email protected] This is the time of year when Jazz Rag readers expect to have the opportunity to vote for the Jazz Oscars, the British Jazz Awards. -

The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18Th Century Great Britain

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain Scott H. Zurawel Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Zurawel, Scott H., "The unL ar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in 18th Century Great Britain" (2011). Honors Theses. 1092. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1092 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i THE LUNAR SOCIETY OF BIRMINGHAM AND THE PRACTICE OF SCIENCE IN 18TH CENTURY GREAT BRITAIN: A STUDY OF JOSPEH PRIESTLEY, JAMES WATT AND WILLIAM WITHERING By Scott Henry Zurawel ******* Submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE March, 2011 ii ABSTRACT Zurawel, Scott The Lunar Society of Birmingham and the Practice of Science in Eighteenth-Century Great Britain: A Study of Joseph Priestley, James Watt, and William Withering This thesis examines the scientific and technological advancements facilitated by members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham in eighteenth-century Britain. The study relies on a number of primary sources, which range from the regular correspondence of its members to their various published scientific works. The secondary sources used for this project range from comprehensive books about the society as a whole to sources concentrating on particular members. -

Thomas Hickey”, Apollo, III, 1926, Pp

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 Online edition HICKEY, Thomas fixed by some robust process. In his later career Dublin .V.1741 – Madras .V.1824 he continued to make black and white chalk The son of Noah Hickey, a confectioner in drawings capturing his sitters’ spontaneous Dublin, he was a pupil of Robert West (q.v.) at expressions: William Sydenham reported to the Dublin Society school, where he won prizes Humphry in a letter of 10.X.1800 that Hickey between 1753 and 1756. His brother John had been “very successful in making black chalk (1751–1795) was a sculptor. He travelled to Italy portraits as preparatory studies” for his series of between 1761 and 1767 before returning to seven paintings of the “success at Mysore”, no Dublin for three years, after which he moved to doubt the fourth Anglo-Mysore war which England. He was admitted to the Royal resulted in the death of Tipu Sultan. Academy Schools in London on 11.VI.1771, and Bibliography exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1772 Archer 1979; Bénézit; Thomas Bodkin, and 1792 (from Jermyn Street, 1772; Tavistock “Thomas Hickey”, Apollo, III, 1926, pp. 96ff; Row, 1773; Henrietta Street, 1774, Gerard Breeze 1983; Breeze 1984; Crookshank 1969; Street, 1775–76; Bath, 1778; and 31 Margaret Crookshank & Glin 1994; Crookshank & Glin J.39.106 William Monckton-Arundell, né Street, 1792). Boswell records dining with 2002; Dictionary of Irish biography; Dublin 1969; Monckton, 2nd Viscount GALWAY (1725– Hickey and Dr Johnson in 1775 shortly before Figgis 2014; Figgis & Rooney 2001; Sir William 1772), MP, master of staghounds, pstl/ppr, his move to Bath where he is recorded between Foster, “British artists in India”, Walpole Society, c.25x20 ov. -

Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850 Thesis How to cite: Mcdermott, Siobhan Clare (2019). Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ed14 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Irish Travelling Artists: Ireland, Southern Asia and the British Empire 1760-1850 Siobhan Claire McDermott, BA, MA, Open University, MB, BAO, BCh, Trinity College Dublin. Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History, School of Arts and Culture, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, the Open University, September, 2018. Personal Statement No part of this thesis has previously been submitted for a degree or other qualification of the Open University or any other university or institution. It is entirely the work of the author. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to show that Irish art made in the period under discussion, the late-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, should not be considered solely in terms of Ireland’s relationship with England as heretofore, but rather, within the framework of the wider British Empire. -

Soho Depicted: Prints, Drawings and Watercolours of Matthew Boulton, His Manufactory and Estate, 1760-1809

SOHO DEPICTED: PRINTS, DRAWINGS AND WATERCOLOURS OF MATTHEW BOULTON, HIS MANUFACTORY AND ESTATE, 1760-1809 by VALERIE ANN LOGGIE A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History of Art College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the ways in which the industrialist Matthew Boulton (1728-1809) used images of his manufactory and of himself to help develop what would now be considered a ‘brand’. The argument draws heavily on archival research into the commissioning process, authorship and reception of these depictions. Such information is rarely available when studying prints and allows consideration of these images in a new light but also contributes to a wider debate on British eighteenth-century print culture. The first chapter argues that Boulton used images to convey messages about the output of his businesses, to draw together a diverse range of products and associate them with one site. Chapter two explores the setting of the manufactory and the surrounding estate, outlining Boulton’s motivation for creating the parkland and considering the ways in which it was depicted. -

Download Spring 2015

LAUREN ACAMPORA CHARLES BRACELEN FLOOD JOHN LeFEVRE BELINDA BAUER ROBERT GODDARD DONNA LEON MARK BILLINGHAM FRANCISCO GOLDMAN VAL McDERMID BEN BLATT & LEE HALL with TERRENCE McNALLY ERIC BREWSTER TOM STOPPARD & ELIZABETH MITCHELL MARK BOWDEN MARC NORMAN VIET THANH NGUYEN CHRISTOPHER BROOKMYRE WILL HARLAN JOYCE CAROL OATES MALCOLM BROOKS MO HAYDER P. J. O’ROURKE KEN BRUEN SUE HENRY DAVID PAYNE TIM BUTCHER MARY-BETH HUGHES LACHLAN SMITH ANEESH CHOPRA STEVE KETTMANN MARK HASKELL SMITH BRYAN DENSON LILY KING ANDY WARHOL J. P. DONLEAVY JAMES HOWARD KUNSTLER KENT WASCOM GWEN EDELMAN ALICE LaPLANTE JOSH WEIL MIKE LAWSON Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, 12 FL, New York, New York 10011 GROVE PRESS Hardcovers APRIL A startling debut novel from a powerful new voice featuring one of the most remarkable narrators of recent fiction: a conflicted subversive and idealist working as a double agent in the aftermath of the Vietnam War The Sympathizer Viet Thanh Nguyen MARKETING Nguyen is an award-winning short story “Magisterial. A disturbing, fascinating and darkly comic take on the fall of writer—his story “The Other Woman” Saigon and its aftermath and a powerful examination of guilt and betrayal. The won the 2007 Gulf Coast Barthelme Prize Sympathizer is destined to become a classic and redefine the way we think about for Short Prose the Vietnam War and what it means to win and to lose.” —T. C. Boyle Nguyen is codirector of the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network and edits a profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer blog on Vietnamese arts and culture is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs Published to coincide with the fortieth A clash with his individual loyalties. -

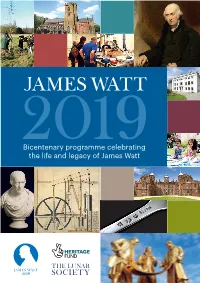

Bicentenary Programme Celebrating the Life and Legacy of James Watt

Bicentenary programme celebrating the life and legacy of James Watt 2019 marks the 200th anniversary of the death of the steam engineer James Watt (1736-1819), one of the most important historic figures connected with Birmingham and the Midlands. Born in Greenock in Scotland in 1736, Watt moved to Birmingham in 1774 to enter into a partnership with the metalware manufacturer Matthew Boulton. The Boulton & Watt steam engine was to become, quite literally, one of the drivers of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and around the world. Although best known for his steam engine work, Watt was a man of many other talents. At the start of his career he worked as both a mathematical instrument maker and a civil engineer. In 1780 he invented the first reliable document copier. He was also a talented chemist who was jointly responsible for proving that water is a compound rather than an element. He was a member of the famous Lunar Portrait of James Watt by Sir Thomas Lawrence, 1812 Society of Birmingham, along with other Photo by Birmingham Museums Trust leading thinkers such as Matthew Boulton, Erasmus Darwin, Joseph Priestley and The 2019 James Watt Bicentenary Josiah Wedgwood. commemorative programme is The Boulton & Watt steam engine business coordinated by the Lunar Society. was highly successful and Watt became a We are delighted to be able to offer wealthy man. In 1790 he built a new house, a wide-ranging programme of events Heathfield Hall in Handsworth (demolished and activities in partnership with a in 1927). host of other Birmingham organisations. Following his retirement in 1800 he continued to develop new inventions For more information about the in his workshop at Heathfield. -

Accounting and Labour Control at Boulton and Watt, C. 1775-1810

This is a repository copy of Accounting and Labour Control at Boulton and Watt, c. 1775- 1810. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/11233/ Monograph: Toms, S. (2010) Accounting and Labour Control at Boulton and Watt, c. 1775-1810. Working Paper. Department of Management Studies, University of York Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 11233 Working Paper Toms, S (2010) Accounting and Labour Control at Boulton and Watt, c. 1775-1810 Working paper number 52. White Rose Research Online [email protected] University of York The York Management School Working Paper No. 52 ISSN Number: 1743-4041 March 2010 Accounting and Labour Control at Boulton and Watt, c. -

Craft Focus Magazine

www.craftfocus.com April/May 2010 April/May CRAFTFOCUS Issue 18 www.craftfocus.com MAGAZINE Happy Birthday Craft Focus! REVIEWS • Craft Hobby + Stitch International • CHA Winter Show TRIED AND TESTED KNITTING YARN How card making is evolving Does e-commerce work for your business? PLUS WIN! Latest products £500 worth of Numberjacks craft Industry profiles kits from Creativity International News & views Position Yourself for the Economic Recovery! Just turn the page to discover how leading UK retailers and manufacturers plan to grow their business in 2010! Give Your Business a Competitive Join us on a Special Reader Trip to the 27-29 Stephens Con Rosemont, Illinois - j “It’s the ideal platform for UK manufacturers and retailers to learn more about the US craft business and the way it operates. Many UK companies that have ventured into the important US market have used the Show as a starting point before committing full-scale.” - Sara Davies, Sales Director at Crafter’s Companion Discover Trends Before Your Competitors X Superb access to craft industry design, manufacturing and retail trends from across the globe X Engage with hundreds of exhibitors and thousands of attendees representing a vast selection of product categories across: B Scrapbooking and Papercrafts B Fabric, Quilting and Needlecrafts B Art Materials and Framing B General Crafts Edge and Find Inspiration in Chicago CHA 2010 Summer Convention & Trade Show July 2010 nvention Center just outside of Chicago Build Your Business with World Class Education X Business building seminars that provide attendees with ideas and strategies they can immediately apply to their own businesses. -

Obtaining a Royal Privilege in France for the Watt Engine, 1776-1786 Paul Naegel, Pierre Teissier

Obtaining a Royal Privilege in France for the Watt Engine, 1776-1786 Paul Naegel, Pierre Teissier To cite this version: Paul Naegel, Pierre Teissier. Obtaining a Royal Privilege in France for the Watt Engine, 1776- 1786. The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology, 2013, 83, pp.96 - 118. 10.1179/1758120612Z.00000000021. hal-01591127 HAL Id: hal-01591127 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01591127 Submitted on 20 Sep 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. int. j. for the history of eng. & tech., Vol. 83 No. 1, January 2013, 96–118 Obtaining a Royal Privilege in France for the Watt Engine (1776–1786) Paul Naegel and Pierre Teissier Centre François Viète, Université de Nantes, France Based on unpublished correspondence and legal acts, the article tells an unknown episode of Boulton and Watt’s entrepreneurial saga in eighteenth- century Europe. While the Watt engine had been patented in 1769 in Britain, the two associates sought to protect their invention across the Channel in the 1770s. They coordinated a pragmatic strategy to enrol native allies who helped them to obtain in 1778 an exclusive privilege from the King’s Council to exploit their engine but this had the express condition of its superiority being proven before experts of the Royal Academy of Science. -

YOUNG PEOPLE and BRITISH IDENTITY Gayatri Ganesh, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI 79-81 Borough Road London SE1 1FY

YOUNG AND BRITISHY PEOPLEIDENTIT Research Study Conducted for The Camelot Foundation by Ipsos MORI Contact Details This research was carried out by the Ipsos MORI Qualitative HotHouse: Annabelle Phillips, Research Director, Ipsos MORI YOUNG PEOPLE AND BRITISH IDENTITY Gayatri Ganesh, Senior Research Executive, Ipsos MORI 79-81 Borough Road London SE1 1FY. Tel: 020 7347 3000 Fax: 020 7347 3800 Email: fi [email protected] Internet: www.ipsos-mori.com ©Ipsos MORI/Camelot Foundation J28609 CCheckedhecked & AApproved:pproved: MModels:odels: Annabelle Phillips Pedro Moro Gayatri Ganesh Brandon Palmer Sarah Castell Triston Davis Rachel Sweetman Fiona Bond Joe Lancaster Laura Grievson Samantha Hyde Nosheen Akhtar Helen Bryant Zabeen Akhtar Emma Lynass PPhotographyhotography & DDesign:esign: Diane Hutchison Jay Poyser Dan Rose Julia Burstein CONTENTS Forward.....1 Acknowledgements.....2 Background and Objectives 3 Methodology.....4 Qualitative phase.....4 The group composition.....5 Quantitative phase.....6 Interpretation of qualitative research.....6 Semiotics.....7 Interpretation of semiotics.....9 Report structure.....10 Publication of data.....10 Executive summary 11 Young people’s lives today.....13 The challenge of Britishness.....14 Where next for British youth identity?.....16 Young people in Britain today 19 Young people’s lives today.....21 My identity.....21 My local area.....23 Young people’s views on living in Britain.....28 Where is the concept of Britain relevant.....30 National and ethnic identities 37 England.....39 -

Tv Advertised Lp's

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS TV ADVERTISED LABELS 1970 to 1992 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, SEPTEMBER 2018 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS MANY THANKS TO PAUL ELLWOOD FOR HELP WITH J & B. ANDREW RENAUT’S WEBSITE LISTS MANY OF THE MAJESTIC / K-TEL COMPILATIONS: https://majesticcompilations.com/ CONCEPT RECORDS CONCEPT RECORD PTY LTD, 139 MURRAY ST, PYRMONT, 2009 // 37 WHITING ST, ARTARMON, 2064. BEGUN BY THEO TAMBAKIS AS A J & B SPECIAL PRODUCTS LABEL. ACTIVE FROM 1984. CC 0001 BREAKIN’ IT UP VARIOUS 1984 CC 0002 HOWLIN’ FOR HITS 2LP VARIOUS 1984 CC 0003 LOVE THEMES INSPIRED BY TORVILL & DEAN VARIOUS CC 0004 THAT’S WHAT I CALL ROCK ‘N’ ROLL VARIOUS CC 0005 THE BOP WON’T STOP VARIOUS 1985 CC 0006 THE HITS HITS HITS MACHINE 2LP VARIOUS 1985 CC 0007 MASTERWORKS COLLECTION VARIOUS 1985 CC 0008 CC 0009 LOVE ME GENTLY VARIOUS CC 0010 4 STAR COUNTRY 2LP DUSTY, REEVES, WHITMAN, WILLIAMS CC 0011 CC 0012 THE DANCE TAPES VARIOUS 1985 CC 0013 KISS-THE SINGLES KISS 1985 CC 0014 THE VERY BEST OF BRENDA LEE 2LP BRENDA LEE 1985 CC 0015 SOLID R.O.C.K. VARIOUS 1985 CC 0016 CC 0017 CC 0018 HIT AFTER HIT VARIOUS 1985 CC 0019 BANDS OF GOLD 2LP VARIOUS CC 0020 THE EXTENDED HIT SUMMER 2LP VARIOUS 1985 CC 0021 METAL MADNESS 2LP VARIOUS 1985 CC 0022 FROM THE HEART VARIOUS 1986 CC 0023 STEPPIN’ TO THE BEAT VARIOUS 1986 CC 0024 STARDUST MELODIES NAT KING COLE CC 0025 THE VERY BEST OF OZ ROCK 2LP VARIOUS 1986 CC 0026 SHE BOP VARIOUS 1986 CC 0027 TI AMO VARIOUS 1986 CC 0028 JUMP ‘N’ JIVE VARIOUS 1986 CC 0029 TRUE LOVE WAYS VARIOUS 1986 CC 0030 PUTTIN’ ON