SOCRATES—A Simple Model for Predicting Long-Term Changes in Soil Organic Carbon in Terrestrial Ecosystems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tillage and Soil Ecology: Partners for Sustainable Agriculture

Soil & Tillage Research 111 (2010) 33–40 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Soil & Tillage Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/still Review Tillage and soil ecology: Partners for sustainable agriculture Jean Roger-Estrade a,b,*, Christel Anger b, Michel Bertrand b, Guy Richard c a AgroParisTech, UMR 211 INRA/AgroParisTech., Thiverval-Grignon, 78850, France b INRA, UMR 211 INRA/AgroParisTech. Thiverval-Grignon, 78850, France c INRA, UR 0272 Science du sol, Centre de recherche d’Orle´ans, Orle´ans, 45075, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Much of the biodiversity of agroecosystems lies in the soil. The functions performed by soil biota have Tillage major direct and indirect effects on crop growth and quality, soil and residue-borne pests, diseases Soil ecology incidence, the quality of nutrient cycling and water transfer, and, thus, on the sustainability of crop Agroecosystems management systems. Farmers use tillage, consciously or inadvertently, to manage soil biodiversity. Soil biota Given the importance of soil biota, one of the key challenges in tillage research is understanding and No tillage Plowing predicting the effects of tillage on soil ecology, not only for assessments of the impact of tillage on soil organisms and functions, but also for the design of tillage systems to make the best use of soil biodiversity, particularly for crop protection. In this paper, we first address the complexity of soil ecosystems, the descriptions of which vary between studies, in terms of the size of organisms, the structure of food webs and functions. We then examine the impact of tillage on various groups of soil biota, outlining, through examples, the crucial effects of tillage on population dynamics and species diversity. -

Soil As a Huge Laboratory for Microorganisms

Research Article Agri Res & Tech: Open Access J Volume 22 Issue 4 - September 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Mishra BB DOI: 10.19080/ARTOAJ.2019.22.556205 Soil as a Huge Laboratory for Microorganisms Sachidanand B1, Mitra NG1, Vinod Kumar1, Richa Roy2 and Mishra BB3* 1Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya, India 2Department of Biotechnology, TNB College, India 3Haramaya University, Ethiopia Submission: June 24, 2019; Published: September 17, 2019 *Corresponding author: Mishra BB, Haramaya University, Ethiopia Abstract Biodiversity consisting of living organisms both plants and animals, constitute an important component of soil. Soil organisms are important elements for preserved ecosystem biodiversity and services thus assess functional and structural biodiversity in arable soils is interest. One of the main threats to soil biodiversity occurred by soil environmental impacts and agricultural management. This review focuses on interactions relating how soil ecology (soil physical, chemical and biological properties) and soil management regime affect the microbial diversity in soil. We propose that the fact that in some situations the soil is the key factor determining soil microbial diversity is related to the complexity of the microbial interactions in soil, including interactions between microorganisms (MOs) and soil. A conceptual framework, based on the relative strengths of the shaping forces exerted by soil versus the ecological behavior of MOs, is proposed. Plant-bacterial interactions in the rhizosphere are the determinants of plant health and soil fertility. Symbiotic nitrogen (N2)-fixing bacteria include the cyanobacteria of the genera Rhizobium, Free-livingBradyrhizobium, soil bacteria Azorhizobium, play a vital Allorhizobium, role in plant Sinorhizobium growth, usually and referred Mesorhizobium. -

Dynamics of Carbon 14 in Soils: a Review C

Radioprotection, Suppl. 1, vol. 40 (2005) S465-S470 © EDP Sciences, 2005 DOI: 10.1051/radiopro:2005s1-068 Dynamics of Carbon 14 in soils: A review C. Tamponnet Institute of Radioprotection and Nuclear Safety, DEI/SECRE, CADARACHE, BP. 1, 13108 Saint-Paul-lez-Durance Cedex, France, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. In terrestrial ecosystems, soil is the main interface between atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere and biosphere. Its interactions with carbon cycle are primordial. Information about carbon 14 dynamics in soils is quite dispersed and an up-to-date status is therefore presented in this paper. Carbon 14 dynamics in soils are governed by physical processes (soil structure, soil aggregation, soil erosion) chemical processes (sequestration by soil components either mineral or organic), and soil biological processes (soil microbes, soil fauna, soil biochemistry). The relative importance of such processes varied remarkably among the various biomes (tropical forest, temperate forest, boreal forest, tropical savannah, temperate pastures, deserts, tundra, marshlands, agro ecosystems) encountered in the terrestrial ecosphere. Moreover, application for a simplified modelling of carbon 14 dynamics in soils is proposed. 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of carbon 14 of anthropic origin in the environment has been quite early a matter of concern for the authorities [1]. When the behaviour of carbon 14 in the environment is to be modelled, it is an absolute necessity to understand the biogeochemical cycles of carbon. One can distinguish indeed, a global cycle of carbon from different local cycles. As far as the biosphere is concerned, pedosphere is considered as a primordial exchange zone. Pedosphere, which will be named from now on as soils, is mainly located at the interface between atmosphere and lithosphere. -

Soil Carbon Science for Policy and Practice Soil-Based Initiatives to Mitigate Climate Change and Restore Soil Fertility Both Rely on Rebuilding Soil Organic Carbon

comment Soil carbon science for policy and practice Soil-based initiatives to mitigate climate change and restore soil fertility both rely on rebuilding soil organic carbon. Controversy about the role soils might play in climate change mitigation is, consequently, undermining actions to restore soils for improved agricultural and environmental outcomes. Mark A. Bradford, Chelsea J. Carey, Lesley Atwood, Deborah Bossio, Eli P. Fenichel, Sasha Gennet, Joseph Fargione, Jonathan R. B. Fisher, Emma Fuller, Daniel A. Kane, Johannes Lehmann, Emily E. Oldfeld, Elsa M. Ordway, Joseph Rudek, Jonathan Sanderman and Stephen A. Wood e argue there is scientific forestry, soil carbon losses via erosion and carbon, vary markedly within a field. Even consensus on the need to decomposition have generally exceeded within seemingly homogenous fields, a Wrebuild soil organic carbon formation rates of soil carbon from plant high spatial density of soil observations is (hereafter, ‘soil carbon’) for sustainable land inputs. Losses associated with these land therefore required to detect the incremental stewardship. Soil carbon concentrations and uses are substantive globally, with a mean ‘signal’ of management effects on soil carbon stocks have been reduced in agricultural estimate to 2-m depth of 133 Pg carbon8, from the local ‘noise’11. Given the time soils following long-term use of practices equivalent to ~63 ppm atmospheric CO2. and expense of acquiring a high density of such as intensive tillage and overgrazing. Losses vary spatially by type and duration observations, most current soil sampling is Adoption of practices such as cover crops of land use, as well as biophysical conditions too limited to reliably quantify management and silvopasture can protect and rebuild such as soil texture, mineralogy, plant effects at field scales9,10. -

The Nature and Dynamics of Soil Organic Matter: Plant Inputs, Microbial Transformations, and Organic Matter Stabilization

Soil Biology & Biochemistry 98 (2016) 109e126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Soil Biology & Biochemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/soilbio Review paper The nature and dynamics of soil organic matter: Plant inputs, microbial transformations, and organic matter stabilization Eldor A. Paul Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory and Department of Soil and Crop Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523-1499, USA article info abstract Article history: This review covers historical perspectives, the role of plant inputs, and the nature and dynamics of soil Received 19 November 2015 organic matter (SOM), often known as humus. Information on turnover of organic matter components, Received in revised form the role of microbial products, and modeling of SOM, and tracer research should help us to anticipate 31 March 2016 what future research may answer today's challenges. Our globe's most important natural resource is best Accepted 1 April 2016 studied relative to its chemistry, dynamics, matrix interactions, and microbial transformations. Humus has similar, worldwide characteristics, but varies with abiotic controls, soil type, vegetation inputs and composition, and the soil biota. It contains carbohydrates, proteins, lipids, phenol-aromatics, protein- Keywords: Soil organic matter derived and cyclic nitrogenous compounds, and some still unknown compounds. Protection of trans- 13C formed plant residues and microbial products occurs through spatial inaccessibility-resource availability, 14C aggregation of mineral and organic constituents, and interactions with sesquioxides, cations, silts, and Plant residue decomposition clays. Tracers that became available in the mid-20th century made the study of SOM dynamics possible. Soil carbon dynamics Carbon dating identified resistant, often mineral-associated, materials to be thousands of years old, 13 Humus especially at depth in the profile. -

Agricultural Soil Carbon Credits: Making Sense of Protocols for Carbon Sequestration and Net Greenhouse Gas Removals

Agricultural Soil Carbon Credits: Making sense of protocols for carbon sequestration and net greenhouse gas removals NATURAL CLIMATE SOLUTIONS About this report This synthesis is for federal and state We contacted each carbon registry and policymakers looking to shape public marketplace to ensure that details investments in climate mitigation presented in this report and through agricultural soil carbon credits, accompanying appendix are accurate. protocol developers, project developers This report does not address carbon and aggregators, buyers of credits and accounting outside of published others interested in learning about the protocols meant to generate verified landscape of soil carbon and net carbon credits. greenhouse gas measurement, reporting While not a focus of the report, we and verification protocols. We use the remain concerned that any end-use of term MRV broadly to encompass the carbon credits as an offset, without range of quantification activities, robust local pollution regulations, will structural considerations and perpetuate the historic and ongoing requirements intended to ensure the negative impacts of carbon trading on integrity of quantified credits. disadvantaged communities and Black, This report is based on careful review Indigenous and other communities of and synthesis of publicly available soil color. Carbon markets have enormous organic carbon MRV protocols published potential to incentivize and reward by nonprofit carbon registries and by climate progress, but markets must be private carbon crediting marketplaces. paired with a strong regulatory backing. Acknowledgements This report was supported through a gift Conservation Cropping Protocol; Miguel to Environmental Defense Fund from the Taboada who provided feedback on the High Meadows Foundation for post- FAO GSOC protocol; Radhika Moolgavkar doctoral fellowships and through the at Nori; Robin Rather, Jim Blackburn, Bezos Earth Fund. -

Measuring Soil Carbon Change

Measuring soil carbon change Peter Donovan version: October 2013 This guide can be freely copied and adapted, with attribution, no commercial use, and derivative works similarly licensed. Contents What this guide is about, and how to use it iv 1 The work of the biosphere 1 1.1 Technology . 1 1.2 The carbon cycle . 2 1.3 Let, not make . 3 1.4 Monitoring: a strategic and creative choice . 4 2 Measuring soil carbon 7 2.1 Purpose, result, and uncertainty . 7 2.2 Change . 9 2.3 Organic and inorganic soil carbon . 11 2.4 Laboratory tests . 12 2.5 Getting started . 14 3 Site selection and sampling design 15 3.1 Mapping your site . 15 3.2 Stratification . 15 3.3 Locating plots . 17 3.4 Sampling tools . 17 3.5 Sampling intensity within the plot . 17 4 Sampling and field procedures 20 4.1 Lay out a transect and mark the plot center . 20 4.2 Soil surface observations . 23 4.3 Lay out the plot . 23 4.4 Use probe to take samples . 24 4.5 Soils with abundant rocks, gravel, or coarse fragments . 24 4.6 Characterize the soil . 25 4.7 Bag the sample . 26 4.8 Going deeper . 26 4.9 Sampling for bulk density . 27 4.10 Resampling . 29 4.11 Correcting for changes in bulk density . 29 ii 5 Getting your samples analyzed 31 5.1 Sample preparation . 31 5.2 Storing samples . 32 5.3 Split sampling to test your lab . 32 5.4 U.S. labs that do elemental analysis or dry combustion test . -

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020

REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE and the SOIL CARBON SOLUTION SEPTEMBER 2020 AUTHORED BY: Jeff Moyer, Andrew Smith, PhD, Yichao Rui, PhD, Jennifer Hayden, PhD REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE IS A WIN-WIN-WIN CLIMATE SOLUTION that is ready for widescale implementation now. WHAT ARE WE WAITING FOR? Table of Contents 3 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 9 A Potent Corrective 11 Regenerative Principles for Soil Health and Carbon Sequestration 13 Biodiversity Below Ground 17 Biodiversity Above Ground 25 Locking Carbon Underground 26 The Question of Yields 28 Taking Action ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 30 Soil Health for a Livable Future Many thanks to the Paloma Blanca Foundation and Tom and Terry Newmark, owners of Finca Luna Nueva Lodge and regenerative farm in 31 References Costa Rica, for providing funding for this paper. Tom is also the co-founder and chairman of The Carbon Underground. Thank you to Roland Bunch, Francesca Cotrufo, PhD, David Johnson, PhD, Chellie Pingree, and Richard Teague, PhD for providing interviews to help inform the paper. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The environmental impacts of agricultural practices This introduction is co-authored by representatives of two The way we manage agricultural land 140 billion new tons of CO2 contamination to the blanket of and translocation of carbon from terrestrial pools to formative organizations in the regenerative movement. matters. It matters to people, it matters to greenhouse gases already overheating our planet. There is atmospheric pools can be seen and felt across a broad This white paper reflects the Rodale Institute’s unique our society, and it matters to the climate. no quarreling with this simple but deadly math: the data are unassailable. -

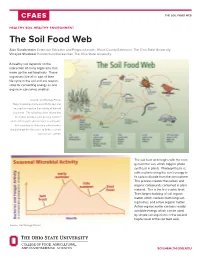

The Soil Food Web

THE SOIL FOOD WEB HEALTHY SOIL HEALTHY ENVIRONMENT The Soil Food Web Alan Sundermeier Extension Educator and Program Leader, Wood County Extension, The Ohio State University. Vinayak Shedekar Postdoctural Researcher, The Ohio State University. A healthy soil depends on the interaction of many organisms that make up the soil food web. These organisms live all or part of their life cycle in the soil and are respon- sible for converting energy as one organism consumes another. Source: Soil Biology Primer The phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) test can be used to measure the activity of the soil food web. The following chart shows that mi-crobial activity peaks in early summer when soil is warm and moisture is adequate. Soil sampling for detecting soil microbes should follow this timetable to better capture soil microbe activity. The soil food web begins with the ener- gy from the sun, which triggers photo- synthesis in plants. Photosynthesis re- sults in plants using the sun’s energy to fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This process creates the carbon and organic compounds contained in plant material. This is the first trophic level. Then begins building of soil organic matter, which contains both long-last- ing humus, and active organic matter. Active organic matter contains readily available energy, which can be used by simple soil organisms in the second trophic level of the soil food web. Source: Soil Biology Primer SOILHEALTH.OSU.EDU THE SOIL FOOD WEB - PAGE 2 The second trophic level contains simple soil organisms, which Agriculture can enhance the soil food web to create more decompose plant material. -

Unit 2.3, Soil Biology and Ecology

2.3 Soil Biology and Ecology Introduction 85 Lecture 1: Soil Biology and Ecology 87 Demonstration 1: Organic Matter Decomposition in Litter Bags Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 101 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 103 Demonstration 2: Soil Respiration Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 105 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 107 Demonstration 3: Assessing Earthworm Populations as Indicators of Soil Quality Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 111 Step-by-Step Instructions for Students 113 Demonstration 4: Soil Arthropods Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 115 Assessment Questions and Key 117 Resources 119 Appendices 1. Major Organic Components of Typical Decomposer 121 Food Sources 2. Litter Bag Data Sheet 122 3. Litter Bag Data Sheet Example 123 4. Soil Respiration Data Sheet 124 5. Earthworm Data Sheet 125 6. Arthropod Data Sheet 126 Part 2 – 84 | Unit 2.3 Soil Biology & Ecology Introduction: Soil Biology & Ecology UNIT OVERVIEW MODES OF INSTRUCTION This unit introduces students to the > LECTURE (1 LECTURE, 1.5 HOURS) biological properties and ecosystem The lecture covers the basic biology and ecosystem pro- processes of agricultural soils. cesses of soils, focusing on ways to improve soil quality for organic farming and gardening systems. The lecture reviews the constituents of soils > DEMONSTRATION 1: ORGANIC MATTER DECOMPOSITION and the physical characteristics and soil (1.5 HOURS) ecosystem processes that can be managed to In Demonstration 1, students will learn how to assess the improve soil quality. Demonstrations and capacity of different soils to decompose organic matter. exercises introduce students to techniques Discussion questions ask students to reflect on what envi- used to assess the biological properties of ronmental and management factors might have influenced soils. -

Age of Soil Organic Matter and Soil Respiration: Radiocarbon Constraints on Belowground C Dynamics

April 2000 BELOWGROUND PROCESSES AND GLOBAL CHANGE 399 Ecological Applications, 10(2), 2000, pp. 399±411 q 2000 by the Ecological Society of America AGE OF SOIL ORGANIC MATTER AND SOIL RESPIRATION: RADIOCARBON CONSTRAINTS ON BELOWGROUND C DYNAMICS SUSAN TRUMBORE Department of Earth System Science, University of California, Irvine, California 92697-3100 USA Abstract. Radiocarbon data from soil organic matter and soil respiration provide pow- erful constraints for determining carbon dynamics and thereby the magnitude and timing of soil carbon response to global change. In this paper, data from three sites representing well-drained soils in boreal, temperate, and tropical forests are used to illustrate the methods for using radiocarbon to determine the turnover times of soil organic matter and to partition soil respiration. For these sites, the average age of bulk carbon in detrital and Oh/A-horizon organic carbon ranges from 200 to 1200 yr. In each case, this mass-weighted average includes components such as relatively undecomposed leaf, root, and moss litter with much shorter turnover times, and humi®ed or mineral-associated organic matter with much longer turnover times. The average age of carbon in organic matter is greater than the average age predicted for CO2 produced by its decomposition (30, 8, and 3 yr for boreal, temperate, and tropical soil), or measured in total soil respiration (16, 3, and 1 yr). Most of the CO2 produced during decomposition is derived from relatively short-lived soil organic matter (SOM) components that do not represent a large component of the standing stock of soil organic matter. Estimates of soil carbon turnover obtained by dividing C stocks by hetero- trophic respiration ¯uxes, or from radiocarbon measurements of bulk SOM, are biased to longer time scales of C cycling. -

Interpreting, Measuring, and Modeling Soil Respiration

Biogeochemistry (2005) 73: 3–27 Ó Springer 2005 DOI 10.1007/s10533-004-5167-7 -1 Interpreting, measuring, and modeling soil respiration MICHAEL G. RYAN1,2,* and BEVERLY E. LAW3 1US Department of Agriculture-Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 240 West Pros- pect Street, Fort Collins, CO 80526, USA; 2Affiliate Faculty, Department of Forest, Rangeland and Watershed Stewardship and Graduate Degree Program in Ecology, Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523, USA; 3Department of Forest Science, Oregon State University, 328 Richardson Hall, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Key words: Belowground carbon allocation, Carbon cycling, Carbon dioxide, CO2, Infrared gas analyzers, Methods, Soil carbon, Terrestrial ecosystems Abstract. This paper reviews the role of soil respiration in determining ecosystem carbon balance, and the conceptual basis for measuring and modeling soil respiration. We developed it to provide background and context for this special issue on soil respiration and to synthesize the presentations and discussions at the workshop. Soil respiration is the largest component of ecosystem respiration. Because autotrophic and heterotrophic activity belowground is controlled by substrate availability, soil respiration is strongly linked to plant metabolism, photosynthesis and litterfall. This link dominates both base rates and short-term fluctuations in soil respiration and suggests many roles for soil respiration as an indicator of ecosystem metabolism. However, the strong links between above and belowground processes complicate using soil respiration to understand changes in ecosystem carbon storage. Root and associated mycorrhizal respiration produce roughly half of soil respiration, with much of the remainder derived from decomposition of recently produced root and leaf litter.