020 Breaking the Cycle of Corruption in Nigeria's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science, Schooling and Manpower Production in Nigeria: a Study of Kano State Science Secondary Schools, 1977-1987

Science, Schooling And Manpower Production in Nigeria: A Study of Kano State Science Secondary Schools, 1977-1987 By Abdalla Uba Adamu A Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (D.Phil.) of The University of Sussex, Brighton, England March 1988 Table of Contents Declaration.................................................................................................................................viii Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................ix Abstract...........................................................................................................................................x Map of Nigeria ...........................................................................................................................xii Map Of Kano State Showing The Local Government Areas Where The Four Science Secondary Schools Are Located (Dawakin Tofa, Dawakin Kudu, Ringim And Kafin Hausa)......................................................................................................................xii Chapter 1 .......................................................................................................................................1 Introduction To The Study.......................................................................................................1 1.1 Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

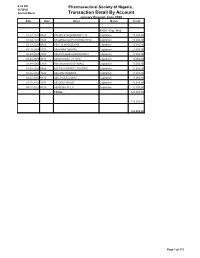

Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria.. 06/30/20 Accrual Basis Transaction Detail by Account January Through June 2020 Date Num Name Memo Credit

4:39 PM Pharmaceutical Society of Nigeria.. 06/30/20 Accrual Basis Transaction Detail By Account January through June 2020 Date Num Name Memo Credit 48001 · Cap Abia 01-27-2020 4841 AB-OBI-EGHOMWARE C.O Capitation 10,000.00 02-04-2020 8545 AB-OSSAI OGECHUKWU RITA Capitation 10,000.00 02-12-2020 9965 AB-C O MADUBUIKE Capitation 10,000.00 02-18-2020 4772 AB-MARK GWARA Capitation 10,000.00 02-20-2020 4955 AB-IKWUEKE FERDINAND C Capitation 10,000.00 02-24-2020 4913 AB-MICHAEL N. UYO Capitation 10,000.00 03-24-2020 5559 AB-URUKWEM ISHMAEL Capitation 10,000.00 03-25-2020 0859 AB-TOCHUKWU E OBIDIKE Capitation 10,000.00 03-26-2020 3043 AB-UZO NGOZIKA Capitation 10,000.00 03-27-2020 8330 AB-OTAKA AGWU Capitation 10,000.00 03-30-2020 1074 AB-ODILI NGOZI Capitation 10,000.00 04-17-2020 4915 AB-MGBAJA L.C Capitation 10,000.00 TOTAL 120,000.00 120,000.00 120,000.00 Page 1 of 213 Date Num Name Memo Credit 48002 · Cap Adamawa 01-27-2020 2060 AD-DAUDA ABDULAMRUFF Capitation 10,000.00 01-30-2020 8325 AD-STEPHEN LABAN Capitation 10,000.00 02-05-2020 1557 AD-RAIHANA BELLO Capitation 10,000.00 02-05-2020 1612 AD-MOHAMMED ALI BAZZA Capitation 10,000.00 02-05-2020 1627 AD-MARKUS ISA Capitation 10,000.00 02-06-2020 5545 AD-PHILIP FAITH Capitation 10,000.00 03-04-2020 Zen030420 AD-ISA A. -

L'état Des Etats Au Nigéria

Service économique régional L’état des Etats au Nigéria 1 Ambassade de France au Nigéria European Union Crescent Off Constitution Avenue Central Business District, Abuja Clause de non-responsabilité : le Service économique s’efforce de diffuser des informations exactes et à jour, et corrigera, dans la mesure du possible, les erreurs qui lui seront signalées. Toutefois, il ne peut en aucun cas être tenu responsable de l’utilisation et de l’interprétation de l’information contenue dans cette publication. L’information sur les projets soutenus par l’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) est donnée à titre purement indicatif. Elle n’est ni exhaustive, ni contractuelle. Un classement par Etats peut être sujet à interprétation, notamment pour des projets nationaux (relatifs à la culture, à la gouvernance…) ou régionaux (coordonnées par la CEDEAO) non mentionnés dans le document. Ce classement n’emporte aucun jugement de valeur et n’est pas une justification de l’aide publique apportée par la France à un Etat fédéré plutôt qu’à un autre. Il peut également être soumis à des changements indépendants de la volonté de l’AFD. 2 Ambassade de France au Nigéria European Union Crescent Off Constitution Avenue Central Business District, Abuja SOMMAIRE Avant-propos .................................................................................................................................................4 Etat d’Abia (Sud-Est) ......................................................................................................................................6 -

Foreign Exchange Auction No 55/2004 of 19Th July, 2004 Foreign Exchange Auction Sales Result Applicant Name Form Bid Cumm

1 CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA, ABUJA TRADE AND EXCHANGE DEPARTMENT FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION NO 55/2004 OF 19TH JULY, 2004 FOREIGN EXCHANGE AUCTION SALES RESULT APPLICANT NAME FORM BID CUMM. BANK Weighted S/N A. QUALIFIED BIDS M/A NO R/C NO APPLICANT ADDRESS RATE AMOUNT AMOUNT PURPOSE NAME Average 1 GNLD INTERNATIONAL LTD. MF0193262 363844 12, CHIEF OLU OSHUNKEYE CRESCENT, 133.5000 38,495.20 38,495.20 PROTEIN POWDER,GR2 VANILLA AND GR2 CHOCOLATE N.I.B 0.0549 2 JUBECAN NIGERIA CO. LTD MF 0472346 RC 73310 NO. 6, VENN ROAD NORTH, ONITSHA, ANA 133.5000 11,680.00 50,175.20 IMPORTATION OF 16MT SHEETS OF COVER PAPER (INDUSTRIAL RAWNAL 0.0167 3 EMPIRE ENGINEERING AND MACHINE TOOMF0559592 RC479599TWEST ROAD,RUMUOKORO,PORTHARCO 133.5000 77,500.00 127,675.20 INDUSTRIAL MACHINES PRUDENT 0.1106 4 OLARINDE AND SONS ENTR.LIMITED MF 0646513 131952 1,BADAGRY EXP.WAY,ORILE IGANMU,LAG 133.5000 71,816.00 199,491.20 1370PCS OF STAINLESS STEELS TUBES WEMA 0.1025 5 ADE-JOHN M.O. AA1264459 A0147733 21, TEMPLE ROAD, IKOYI LAGOS 133.3000 2,000.00 201,491.20 PERSONAL TRAVEL ALLOWANCE UBA 0.0029 6 SOPTIMAL VENTURES LTD MF0567882 RC251347 IFE ROAD,OPPOSITECELECA CHURCH ,IB 133.2000 36,092.00 237,583.20 POULTRY FEED ADDITIVES (L-LYSINE) PRUDENT 0.0514 7 CONSUMER ELECTRONICS NIG LTD MF0578342 458,790 OSHOPEY PLAZA 17/18 ALLEN AVE. IKEJA 133.2000 74,900.00 312,483.20 IMPORTATION OF USED COMPUTER SYSTEMS DESKTOP/TOWER, 486STD. CHRTD 0.1067 8 UNIVERSAL TEXTILES INDUSTRIES LIMITEMF0676006 14311 INDEPENDENCE ROAD, BOMPAI, KANO 133.2000 134,424.00 446,907.20 POLYETHYLENE TREPHALATE, -

View Annual Report

AG HOMES SAVINGS & LOANS PLC RC602252 Annual Report & Accounts 31st December 2013 Our Value Statement We strive to honour God and be respectful of each other, our customers and other stakeholders. Our Vision Statement To be the preferred Primary Mortgage Institution with a commanding presence nation-wide. Our Mission Statement To consistently create value to stakeholders by providing excellent services through creative and caring employees using innovative technology applications in a first class ambience. 1 Annual Report & Accounts 31st December 2013 AG HOMES SAVINGS & LOANS PLC RC602252 Contents Corporate Information 3 Results at a Glance 8 Report of the Directors 9 Report of the Audit Committee 13 Independent Auditors' Report 14 Statement of Comprehensive Income 16 Statement of Financial Position 17 Statement of Changes in Equity 18 Statement of Cash Flows 19 Notes to the Financial Statements 20 Statement of Value Added 56 Five-Year Financial summary 57 2 Annual Report & Accounts 31st December 2013 AG HOMES SAVINGS & LOANS PLC RC602252 CORPORATE INFORMATION Directors Rev. Dr. Vincent Alaje - Acting Chairman Mr. Tony Okechukwu Ewelike - Managing Director/CEO Barr. Patrick Chinweike Abuka - Director Barr. Danjuma Suleman -Director Rev. Dr. Paul Emeka - Director Ngozi Anyogu - Executive Director Company Secretary: Barr. Anthony Okonmah Registered Number: RC 602252 Date of Registration: 21 July, 2004 Operating License Number: 000000005 Date Licensed: 31 December, 2004 Registered Office: 96, Opebi Road, Ikeja, Lagos. Head Office/Opebi Branch: 96 Opebi Road, Ikeja, Lagos. Auditors: Baker Tilly Nigeria, (Chartered Accountants), Kresta Laurel Complex (4th Floor), 376, Ikorodu Road, Maryland,Lagos. Correspondent Banks: United Bank for Africa Plc Access Bank Plc Registrars CardinalStones Registrars Limited 358, Herbert Macaulay Way, Yaba, Lagos ...a partner you can trust 3 Annual Report & Accounts 31st December 2013 AG HOMES SAVINGS & LOANS PLC RC602252 The Board Rev. -

Passion for Polo Passion for Polo

MAY 2013 | VOL 1 ISSUE 4 | N2,000 | £8 Adventures in Luxury Claire Tomlinson Polo’s First Lady Royal Polo Players !e Sport of Kings Marwan Chatila Bond Street’s Most Discreet Jeweller Sayyu Dantata !"hchukker.com !"hchukkermagazine.com Passion for polo 62 82 ContentsMAY 2013 | VOL 1 ISSUE 4 7 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 32 PASSION FOR POLO Ahmed Dasuki How photographer Tony Ramirez 16 turned his passion into a business 9 EDITOR’S WELCOME Funmi Oladeinde-Ogbue 36 GINGER BAKER "e Cream drummer’s THE SEASON Nigerian polo odyssey AT FIFTH CHUKKER 38 KOLA ALUKO 10 ETISALAT AFRICAN Entrepreneur Kola Aluko PATRONS CUP on sport and business All the action from this 40 ROYALTY IN POLO prestigious event Who’s Who in today’s royal players 16 SEEN AT FIFTH CHUKKER Who’s Who in the In Crowd UP CLOSE AND PERSONAL 18 NWANKWO KANU 45 MUSTAPHA SHERIFF Fi!h Chukker’s new “I appreciate the support Charity Ambassador I have had along the way.” 20 COMMISSIONING OF 46 OSA COOKEY THE ADAMU ATTA “I have had a special bond PRIMARY SCHOOL with horses since I was a child.” "e remodelled Fi!h Chukker-funded 48 HADI SIRIKA primary school opens its doors “"e thrill of playing is so special and ful#lling.” POLO PEOPLE 50 SANI UMAR 22 GENERAL HASSSAN KATSINA “I love the thrills that go with riding.” Remembering the legendary polo-playing General ART IN FOCUS 26 PASSION FOR POLO 52 NIC FIDDIAN!GREEN Sayyu Dantata Horse sculptor extraordinaire 28 WOMEN IN POLO 56 KELECHI AMADI!OBI Claire Tomlinson’s trailblazing career Nigeria’s fashion photography genius 30 THE INAUGURAL AFRICAN -

Theme: Optimizing the Economic Development Capacity of the Ajaokuta-Kaduna-Kano “AKK” Gas Pipeline Project

2021 GAS SECTOR STAKEHOLDERS' FORUM – THURSDAY 29th JULY, 2021 IN KANO, KANO STATE. Theme: Optimizing the Economic Development Capacity of the Ajaokuta-Kaduna-Kano “AKK” Gas Pipeline Project T DAY I TOPIC/ACTIVITY PRESENTED BY M Wednesday, 1E Cultural Night/Welcome to Kano & Pre- Forum Registration Planning Committee/KNSG 28th July, 2021 9 : 3 (WELCOME, TECHNICAL SESSIONS & EXHIBITION) 0 – DAY TIME TOPIC/ACTIVITY PRESENTED BY 2 Thursday, 29th 107:30 – 9:00 Registration & Breakfast Session July, 2021 : 0 0 PRE – EVENT OPENING UPDATE SESSION & WELCOME 9:00 – 9:05 Terdoo Akaa (5mins) HSE PRE-EVENT UPDATE SESSION GACN Operations Dept. 9:05 – 9:15 Keynote remarks on GACN operations Mrs. Yemi Famori (10mins) Director, GACN 9:15 – 9:40 Topic: AKK Project Execution Update and completion • Presentation: 20• minsPresentation: 25mins (25mins) schedule. Contributions, Questions• Contributions, and Questions and Answers: 5mins Speaker/Presenter: Answers: 5mins • Engr. Seyi Omotowa MD, Nigerian Gas Company Limited (15mins) 9:40 -9:50 Welcome remarks Engr. Mansur Sambo (10mins) • Chairman, GACN Board 1 FORMAL FORUM OPENING Thursday, 29th 9:50 – 9:54 Opening Prayers (Second Stanza of the National Anthem) Master of Ceremony (MC) July, 2021 (4mins) 9:54 – 10:14 Keynote Address & Forum Opening H. E. President Muhammadu Buhari, (20mins) GCFR Theme for Keynote Address: The imperative of synergetic President of the Federal Republic of Government – Private Sector Partnership to optimize the Nigeria benefits of Major Infrastructure Projects in Nigeria. SESSION 1: INDUSTRY LEADERSHIP OVERVIEW Thursday, 29th 10:14- 10:34 Topic 1: The Significance, Gains & Benefits of the • Presentation: (20 mins) July, 2021 (20 mins) Ongoing Focus On Gas Development. -

Final Shortlisted Candidates

A B C D F 1 2 3 SERIAL REG NO NAME SEX DEPARTMENT 4 ABIA 5 1 NNR2016/AB/709/0046786 UKWUNNA CHINAZA MARGARET F STORE ASSISTANTS 6 2 NNR2016/AB/354/0064812 ONYEIJE OKECHUKWU FAVOUR M WRITERS 7 3 NNR2016/AB/538/0137556 OKEREKE NGOZI NNENNA F SEAMAN 8 4 NNR2016/AB/564/0169218 NWOSU REGINA UKA F SEAMAN 9 5 NNR2016/AB/614/0124068 OLIVER EUCHARIA NKASIOBI F CATERERS 10 6 NNR2016/AB/062/0156107 VERNUMBE EMMANUEL M SEAMAN 11 7 NNR2016/AB/102/0009993 UWADINEKE CHUKWUEMEKA ACKANGEL M BANDSMEN 12 8 NNR2016/AB/102/0047162 OGBONNAYA CHRISTIAN SINCLAIR M INFO TECH 13 9 NNR2016/AB/353/0002341 ORJI BLESSING UCHECHUKWU F STORE ASSISTANTS 14 10 NNR2016/AB/353/0035973 ONUOHA AMARACHI OLUCHI C F NURSES 15 11 NNR2016/AB/353/0064264 ONUOHA ODINAKACHI CLINTON M PT INSTRUCTORS 16 12 NNR2016/AB/353/0153452 ORIOHA UZOMA M SEAMAN 17 13 NNR2016/AB/354/0008349 OGAH MATHEW OGAH M SEAMAN 18 14 NNR2016/AB/354/0023488 NWALA CHUKWUDI VICTOR M CATERERS 19 15 NNR2016/AB/354/0093672 ONUMAEGBU MAUREEN ULOMA F NURSES 20 16 NNR2016/AB/354/0127818 OCHULOR OBINNA VICTOR M PHYSIOTHERAPIST 21 17 NNR2016/AB/354/0170105 NGUMOHA BLESSING CHIDERA F SEAMAN 22 18 NNR2016/AB/538/0094751 OKEH PRINCEWILL CHIAGOZIEM M COMMUNICATIONS 23 19 NNR2016/AB/564/0013444 OKORIE MBA SUNNY M SURVEY RECORDERS 24 20 NNR2016/AB/614/0118273 NJOKU THANKGOD M CHAPLAIN ASSISTANTS 25 21 NNR2016/AB/708/0066351 NWAZUE CHIMDIEBUBE PASCHAL M SEAMAN 26 22 NNR2016/AB/709/0077708 ONYEMACHI AKAJIAKU GRACE F STORE ASSISTANTS 27 23 NNR2016/AB/709/0127189 NWOSU RELINDIS IFEOMA F FIREMEN 28 24 NNR2016/AB/006/0118251 NWEKE -

List of State Governors of Nigeria 2019

LIST OF STATE GOVERNORS OF NIGERIA 2019 STATE GOVERNOR DEPUTY GOVERNOR PARTY Abia State Okezie Ikpeazu Ude Oko Chukwu PDP Adamawa State Ahmadu Umaru Fintiri Crowther Seth PDP Akwa Ibom State Udom Gabriel Emmanuel Moses Ekpo PDP Anambra State Willie Obiano Dr. Nkem Okeke APGA Bauchi State Bala Muhammed Baba Tela PDP Bayelsa State Henry Dickson Gboribiogha John Jonah PDP Benue State Samuel Ortom Benson Abounu PDP[1] Borno State BabaGana Umara Umar Usman Kadafur APC Cross River State Benedict Ayade Ivara Esu PDP Delta State Ifeanyi Okowa Kingsley Otuaro PDP Ebonyi State Dave Umahi Eric Kelechi Igwe PDP Edo State Godwin Obaseki Philip Shaibu APC Ekiti State Kayode Fayemi Kolapo Olushola APC Enugu State Ifeanyi Ugwuanyi Cecilia Ezeilo PDP Gombe State Muhammad Inuwa Yahaya Manasseh Daniel Jatau APC Imo State Chukwuemeka Ihedioha Irona Alphonsus PDP Jigawa State Badaru Abubakar Umar Alhaji Namadi APC Kaduna State Nasir Ahmad el-Rufai Yusuf Barnabas Bala APC Kano State Abdullahi Umar Ganduje Hafiz Abubakar APC Katsina State Aminu Bello Masari Mannir Yakubu APC Kebbi State Abubakar Atiku Bagudu Samaila Yombe Dabai APC Kogi State Yahaya Bello Simon Achuba APC Kwara State AbdulRahman AbdulRasaq Kayode Alibi APC Lagos State Babajide Sanwo-Olu Kadri Obafemi Hamzat APC Nasarawa State Abdullahi Sule Emmanuel Agbadu Akabe APC Niger State Abubakar Sani Bello Ahmed Muhammad Ketso APC Ogun State Dapo Abiodun Salako-Oyedele Noimot Olurotimi APC Ondo State Oluwarotimi Odunayo Akeredolu Agboola Ajayi[2] APC[3] Osun State Adegboyega Oyetola Gboyega Alabi APC Oyo State Oluwaseyi Makinde Engr. Rauf Aderemi Olaniyan PDP Plateau State Simon Lalong Sonni Gwanle Tyoden APC Rivers State Ezenwo Nyesom Wike Ipalibo Banigo PDP Sokoto State Aminu Waziri Tambuwal Ahmad Aliyu PDP Taraba State Arch. -

Download Promoting Economic Prosperity

www.pwc.com/ng Promoting Economic Prosperity Analysis of the State- Level Business Environment in Nigeria 2 Promoting Economic Prosperity PwC 3 Foreword We are pleased to present the findings from the State Level Business Environment Analysis conducted across four Nigerian States (Anambra, Edo, Ogun and Niger). This report has been prepared by PwC in response to a request by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO). The purpose of the study was to: ? Identify challenges and opportunities for doing business, and examples of good practices in the focus states. ? Provide key recommendations as to how the United Kingdom (UK) can broaden prosperity and commercial engagements that help Nigerian states make the most of their economic development opportunities. This report is sequel to the March 2016 publication which evaluates the key sectors of opportunity for UK businesses in Nigeria. To form our conclusions, we have used a combination of quantitative analysis of publicly available data as well as insights gathered from interviews with a sample of private sector companies, key state parastatals, business and trade groups, and development agencies. Our findings show that fostering an environment conducive for business and competitiveness is key to promoting economic prosperity. We would like to use this opportunity to acknowledge and appreciate the support we received from the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), respective state governments, private companies, business and trade groups, development agencies interviewed and PwC’s panel of -

Page 1 of 67 OPERATION AURE 7/21/2008

OPERATION AURE Page 1 of 67 OPERATION 'AURE’: The Northern Military Counter-Rebellion of July 1966 By Nowa Omoigui BACKGROUND In the early hours of January 15, 1966, citing a laundry list of complaints against the political class, there was a military rebellion in Nigeria against the first republic [http://www.dawodu.com/nzeogwu2.htm]. Led by a group of Majors who were predominantly of eastern origin, the Prime Minister, a federal minister, two regional premiers, along with top Army officers were brutally assassinated. A number of civilians were also killed. [http://www.gamji.com/NEWS1103.htm] The coup succeeded in Kaduna the northern region capital, failed in Lagos the federal capital and Ibadan the western regional capital, but barely took place in Benin the midwestern capital, and Enugu the eastern capital. The majority of those murdered were northerners, accompanied by some westerners and two Midwesterners. No easterner lost his or her life. On January 16, rather than approve the appointment of Zanna Bukar Dipcharima, a politician of northern origin, as acting Prime Minister, the acting President, Nwafor Orizu, himself of eastern origin, handed over power to Major-General JTU Aguiyi- Ironsi, the GOC of the Nigerian Army, also of eastern origin. This was allegedly at the behest of the rump cabinet, allegedly to enable Ironsi put down the revolt which, as of then, had already failed in southern Nigeria. Until it became apparent recently in separate testimony by Alhaji Shehu Shagari and Chief Richard Akinjide, it had always been publicly assumed in the lay Press that the hand-over was voluntary although unconstitutional - since no such provision existed in the Nigerian constitution. -

Back-Up-Statistics-On-Killing-Of-Christians-In-Nigeria-Jan-April-2021-2

Back-Up Statistics On Killing Of Christians In Nigeria: Jan-April 2021 65 Communities In Niger Sign N20m Peace Deal with Boko Haram: Residents of 65 communities in Niger State have resorted to negotiating and signing a peace deal with Boko Haram to avoid future raids by the insurgents, FIJ can exclusively report. Abubakar Bello, the Governor of Niger had admitted that Boko Haram had hoisted its flag after taken over many communities in the state. This development came few days after the terror group displaced over 5,000 villagers from their ancestral homes in Shiroro and Munya local councils..FIJ has gathered that communities in Gurmana, Manta, Bassa and Kukoki districts in Shiroro area of the state have negotiated with the terrorists for a peace deal after reaching an agreement to pay certain amounts of money in each community.The communities have also purchased at least six Honda motorcycles worth N500,000 for the terrorists, to pacify them. See the list of the villages below: (1) BASSA/KUKOKI WARD Wongo, Kukoki, Masuku, Zangoro, Gungu, Rumache Madalla, Rumache Gari, Maguga, Marenje, Malawai, Madagwa, Kadaga, Hana Wanka, Durumi, Farar Kasa (2) GURMANA WARD Gurmana, Kokki Makaranta, Kokki Magami, Shekadna, Karibo, Rango, Sarkin Zama, Bakin Kogi (Lagbe), Maganda, Jabukin Sama, Jabukin Kasa, Guto, Gwaja, Sundna, Fiyi, Unguwan Turakin Kokki, Kuchiwi, Tsohon Gari, Kokki Bodo, Palalli, Gbakoita, Kampani, Yelwa, Ajata Aboki, Birke, Jankasa, Kasumi, Kuyami, Siyiko (3) MANTA WARD Manta, Jiko, Gungu, Magami, Gaviya, Sabon Gida, Jankasa, Farin Hula, Taidna, Beri Kago, Beri, Gatawi, Kini, Bmada, Bagudu, Guto, Sunko, Gbagawi, Marafa, Gudumi, Gbaga (Source: Foundation for Investigative Journalism, 30th April 2021).