Warkentin, University of Calgary – Qatar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Fido 1939–2019

May 2019 No. 164 MARTIN FIDO 1939–2019 DAVID BARRAT • MICHAEL HAWLEY • DAVID pinto STEPHEN SENISE • jan bondeson • SPOTLIGHT ON RIPPERCAST NINA & howard brown • THE BIG QUESTION victorian fiction • the latest book reviews Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1 Ripperologist 164 May 2019 EDITORIAL Adam Wood SECRETS OF THE QUEEN’S BENCH David Barrat DEAR BLUCHER: THE DIARY OF JACK THE RIPPER David Pinto TUMBLETY’S SECRET Michael Hawley THE FOURTH SIGNATURE Stephen Senise THE BIG QUESTION: Is there some undiscovered document which contains convincing evidence of the Ripper’s identity? Spotlight on Rippercast THE POLICE, THE JEWS AND JACK THE RIPPER THE PRESERVER OF THE METROPOLIS Nina and Howard Brown BRITAIN’S MOST ANCIENT MURDER HOUSE Jan Bondeson VICTORIAN FICTION: NO LIVING VOICE by THOMAS STREET MILLINGTON Eduardo Zinna BOOK REVIEWS Paul Begg and David Green Ripperologist magazine is published by Mango Books (www.MangoBooks.co.uk). The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its editorial team, but are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of doWe not occasionally necessarily use reflect material the weopinions believe of has the been publisher. placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement. -

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © the Poisoned Pen, Ltd

BOOKNEWS from ISSN 1056–5655, © The Poisoned Pen, Ltd. 4014 N. Goldwater Blvd. Volume 28, Number 11 Scottsdale, AZ 85251 October Booknews 2016 480-947-2974 [email protected] tel (888)560-9919 http://poisonedpen.com Horrors! It’s already October…. AUTHORS ARE SIGNING… Some Events will be webcast at http://new.livestream.com/poisonedpen. SATURDAY OCTOBER 1 2:00 PM Holmes x 2 WEDNESDAY OCTOBER 19 7:00 PM Laurie R King signs Mary Russell’s War (Poisoned Pen $15.99) Randy Wayne White signs Seduced (Putnam $27) Hannah Stories Smith #4 Laurie R King and Leslie S Klinger sign Echoes of Sherlock THURSDAY OCTOBER 20 7:00 PM Holmes (Pegasus $24.95) More stories, and by various authors David Rosenfelt signs The Twelve Dogs of Christmas (St SUNDAY OCTOBER 3 2:00 PM Martins $24.99) Andy Carpenter #14 Jodie Archer signs The Bestseller Code (St Martins $25.99) FRIDAY OCTOBER 21 7:00 PM MONDAY OCTOBER 3 7:00 PM SciFi-Fantasy Club discusses Django Wexler’s The Thousand Kevin Hearne signs The Purloined Poodle (Subterranean $20) Names ($7.99) TUESDAY OCTOBER 4 Ghosts! SATURDAY OCTOBER 22 10:30 AM Carolyn Hart signs Ghost Times Two (Berkley $26) Croak & Dagger Club discusses John Hart’s Iron House Donis Casey signs All Men Fear Me ($15.95) ($15.99) Hannah Dennison signs Deadly Desires at Honeychurch Hall SUNDAY OCTOBER 23 MiniHistoricon ($15.95) Tasha Alexander signs A Terrible Beauty (St Martins $25.99) SATURDAY OCTOBER 8 10:30 AM Lady Emily #11 Coffee and Club members share favorite Mary Stewart novels Sherry Thomas signs A Study in Scarlet Women (Berkley -

<H1>The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes</H1>

The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes The Lodger by Marie Belloc Lowndes "Lover and friend hast thou put far from me, and mine acquaintance into darkness." PSALM lxxxviii. 18 CHAPTER I Robert Bunting and Ellen his wife sat before their dully burning, carefully-banked-up fire. The room, especially when it be known that it was part of a house standing in a grimy, if not exactly sordid, London thoroughfare, was exceptionally clean and well-cared-for. A casual stranger, more particularly one of a Superior class to their own, on suddenly opening the door of that sitting-room; would have thought that Mr. page 1 / 387 and Mrs. Bunting presented a very pleasant cosy picture of comfortable married life. Bunting, who was leaning back in a deep leather arm-chair, was clean-shaven and dapper, still in appearance what he had been for many years of his life--a self-respecting man-servant. On his wife, now sitting up in an uncomfortable straight-backed chair, the marks of past servitude were less apparent; but they were there all the same--in her neat black stuff dress, and in her scrupulously clean, plain collar and cuffs. Mrs. Bunting, as a single woman, had been what is known as a useful maid. But peculiarly true of average English life is the time-worn English proverb as to appearances being deceitful. Mr. and Mrs. Bunting were sitting in a very nice room and in their time--how long ago it now seemed!--both husband and wife had been proud of their carefully chosen belongings. -

1 a DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD: CULTURAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP and the MOBILIZATION of MORALLY TAINTED CULTURAL RESOURCES Elena Dalpiaz Imper

A DOUBLE-EDGED SWORD: CULTURAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE MOBILIZATION OF MORALLY TAINTED CULTURAL RESOURCES Elena Dalpiaz Imperial College Business School Imperial College London South Kensington Campus London SW7 2AZ Tel: +44 (0)20 7594 1969 Email: [email protected] Valeria Cavotta Free University of Bolzano School of Economics and Management Piazza Università 1 39100 - Bozen-Bolzano Tel: +39.0471.013522 Email: [email protected] This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article forthcoming in "Innovation: Organization & Management”. 1 Abstract We aim to highlight a type of cultural entrepreneurship, which has received scant attention by prior scholarship, and consists in deploying morally tainted cultural resources, i.e., resources that some audiences assess as going against accepted principles of morality. We argue that this type of cultural entrepreneurship is a double-edged sword and explain how it may ignite active opposition of offended audiences, as well as attract supportive audiences. We delineate a research agenda to shed light on whether, how, and with what consequences cultural entrepreneurs navigate such a tension — in particular how they 1) mobilize morally tainted cultural resources and with what effect on offended audiences; 2) deal with the consequent legitimacy challenges; 3) transform moral taint into “coolness” to enhance their venture’s distinctiveness. Keywords: cultural entrepreneurship, morality, legitimacy, distinctiveness, cultural resources 2 Introduction Cultural entrepreneurship consists in the deployment of cultural resources to start up new ventures or pursue new market opportunities in established ventures (see Gehman & Soubliere, 2017 for a recent review). Cultural resources are meaning systems such as “stories, frames, categories, rituals, practices” and symbols that constitute the culture of a given societal group (Giorgi, Lockwood, & Glynn, 2015, 13). -

Notions of the Gothic in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock. CLARK, Dawn Karen

Notions of the Gothic in the films of Alfred Hitchcock. CLARK, Dawn Karen. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19471/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version CLARK, Dawn Karen. (2004). Notions of the Gothic in the films of Alfred Hitchcock. Masters, Sheffield Hallam University (United Kingdom).. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Sheffield Hallam University Learning and IT Services Adsetts Centre City Campus Sheffield S1 1WB Return to Learning Centre of issue Fines are charged at 50p per hour REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10694352 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694352 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Notions of the Gothic in the Films of Alfred Hitchcock Dawn Karen Clark A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Master of Philosophy July 2004 Abstract The films of Alfred Hitchcock were made within the confines of the commercial film industries in Britain and the USA and related to popular cultural traditions such as the thriller and the spy story. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films, -

Short Stories by Marie Belloc Lowndes

Short Stories by Marie Belloc Lowndes Short Stories by Marie Belloc Lowndes: A Monstrous Regiment of Women Edited by Elyssa Warkentin Short Stories by Marie Belloc Lowndes: A Monstrous Regiment of Women Edited by Elyssa Warkentin This book first published 2018 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Elyssa Warkentin All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0886-2 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0886-6 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory Note ........................................................................................ 1 Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 The Moving Finger Writes Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 23 According to Meredith Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 47 The Decree Made Absolute Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 66 The Child Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding Aid Prepared by Lisa Deboer, Lisa Castrogiovanni

Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Finding aid prepared by Lisa DeBoer, Lisa Castrogiovanni and Lisa Studier and revised by Diana Bowers-Smith. This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit September 04, 2019 Brooklyn Public Library - Brooklyn Collection , 2006; revised 2008 and 2018. 10 Grand Army Plaza Brooklyn, NY, 11238 718.230.2762 [email protected] Guide to the Brooklyn Playbills and Programs Collection, BCMS.0041 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 7 Historical Note...............................................................................................................................................8 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 8 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Highlights.....................................................................................................................................9 Administrative Information .......................................................................................................................10 Related Materials ..................................................................................................................................... -

NEW RELEASES MP3 CD, CD & LIBRARY DOWNLOAD COMPLETE and UNABRIDGED 1 Introducing Samantha Silva… Samantha Silva Is a Writer and Screenwriter Based in Idaho

JULY– SEPTEMBER 2021 Canada ULVERSCROFT AUDIO NEW RELEASES MP3 CD, CD & LIBRARY DOWNLOAD COMPLETE AND UNABRIDGED 1 Introducing Samantha Silva… Samantha Silva is a writer and screenwriter based in Idaho. She is currently adapting her debut novel, Mr Dickens and His Carol, for the stage. Love and Fury is her latest novel. Introduce us to Love and Fury. Everyone knows Mary Shelley, who gave us Frankenstein, but not everyone knows her mother, who gave us feminism…Wollstonecraft is an enormously important 18th century writer and philosopher who argues and fights with every shred of her being for an end to tyranny, whether of kings, of marriage, or men. She took Edmund Burke head on, supported both the American and French Revolutions…and managed to live as an independent woman, supporting herself as a writer, which is extraordinary for the period. She was famous in her own lifetime, but her reputation was destroyed for a century when her grieving husband, radical philosopher William Godwin, rushed to write a tell-all memoir, including her tragic love affairs, out-of-wedlock child, severe depression, suicide attempts, that scandalised even her admirers. I think we’re still recovering from that loss – trying to recover her. ‘Two centuries later, her fight for gender equality is still the fight, and her presence as necessary as ever.’ What’s your favourite quality about her? It hadn’t occurred to me that my favourite qualities of Wollstonecraft’s – fierce love and rage – are qualities of mine, even if not as attractive in me as they are in her. -

„Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duisburg-Essen Publications Online „Yours truly, Jack the Ripper” Die interdiskursive Faszinationsfigur eines Serienmörders in Spannungsliteratur und Film Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil. im Fach Germanistik am Institut für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Duisburg-Essen Vorgelegt von Iris Müller (geboren in Dortmund) Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Jochen Vogt Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Rolf Parr Tag der Disputation: 26. Mai 2014 Inhalt 1. Vorbemerkungen ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Erkenntnisinteresse .............................................................................. 7 1.2 ‚Jack the Ripper‘ als interdiskursive Faszinationsfigur .......................... 9 1.3 Methodik und Aufbau der Arbeit ......................................................... 11 2. Die kriminalhistorischen Fakten ........................................................... 13 2.1 Quellengrundlage: Wer war ‚Jack the Ripper‘? ................................... 13 2.2 Whitechapel 1888: Der Tatort ............................................................. 14 2.3 Die Morde .......................................................................................... 16 2.3.1 Mary Ann Nichols ................................................................................................ 16 2.3.2 Annie Chapman .................................................................................................. -

EXAMINER Issue 4.Pdf

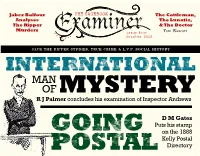

Jabez Balfour THE CASEBOOK The Cattleman, Analyses The Lunatic, The Ripper & The Doctor Murders Tom Wescott issue four October 2010 JACK THE RIPPER STUDIES, TRUE CRIME & L.V.P. SOCIAL HISTORY INTERNatIONAL MAN OF MYSTERY R J Palmer concludes his examination of Inspector Andrews D M Gates Puts his stamp GOING on the 1888 Kelly Postal POStal Directory THE CASEBOOK The contents of Casebook Examiner No. 4 October 2010 are copyright © 2010 Casebook.org. The authors of issue four signed articles, essays, letters, reviews October 2010 and other items retain the copyright of their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication, except for brief quotations where credit is given, may be repro- CONTENTS: duced, stored in a retrieval system, The Lull Before the Storm pg 3 On The Case transmitted or otherwise circulated in any form or by any means, including Subscription Information pg 5 News From Ripper World pg 120 digital, electronic, printed, mechani- On The Case Extra Behind the Scenes in America cal, photocopying, recording or any Feature Stories pg 121 R. J. Palmer pg 6 other, without the express written per- Plotting the 1888 Kelly Directory On The Case Puzzling mission of Casebook.org. The unau- D. M. Gates pg 52 Conundrums Logic Puzzle pg 128 thorized reproduction or circulation of Jabez Balfour and The Ripper Ultimate Ripperologists’ Tour this publication or any part thereof, Murders pg 65 Canterbury to Hampton whether for monetary gain or not, is & Herne Bay, Kent pg 130 strictly prohibited and may constitute The Cattleman, The Lunatic, and copyright infringement as defined in The Doctor CSI: Whitechapel Tom Wescott pg 84 Catherine Eddowes pg 138 domestic laws and international agree- From the Casebook Archives ments and give rise to civil liability and Undercover Investigations criminal prosecution. -

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture

Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith General Editor: Clive Bloom Crime Files Series Editor Clive Bloom Emeritus Professor of English and American Studies Middlesex University London Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/[14927] Clare Smith Jack the Ripper in Film and Culture Top Hat, Gladstone Bag and Fog Clare Smith University of Wales: Trinity St. David United Kingdom Crime Files ISBN 978-1-137-59998-8 ISBN 978-1-137-59999-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-59999-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016938047 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 The author has/have asserted their right to be identifi ed as the author of this work in accor- dance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright.