JPRI Working Paper No. 7: February 1997 Building Japan's Information Superhighway by Joel West If You Want to Know About U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January -2021

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co JANUARY -2021 Banking & Financial Awareness 1. IDBI Bank has sold 23% of its stake in IDBI Federal Life Insurance Company Limited (IFLI) to Ageas Insurance International NV for a consideration of Rs 507 crore. Note: IFLI is a three-way joint venture of IDBI Bank, Belgium’s Ageas and Federal Bank.On purchasing the stake, Ageas Insurance International NV will hold 49% stake in IFLI earlier from 26%. While IDBI Bank’s stake in IFLI will be reduced to 25% from 48%.Federal Bank continues to hold 26 per cent stake in IFLI. 2. The RoDTEP scheme has replaced the popular Merchandise Exports from India Scheme from January 1, 2021. Note: As per the finance ministry the benefit of Remission of Duties and Taxes on Exported Products (RoDTEP) scheme will be extended to all export goods from January 1, 2021.Under the scheme, the embedded central, state and local duties or taxes will get refunded and credited in an exporter’s ledger account with customs. 3. The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) has imposed a fine of rupees Rs 25 crore on Indian company Reliance Industries Ltd. for carrying out manipulative trade. Note: Two more entities, Navi Mumbai SEZ Pvt Ltd and Mumbai SEZ Ltd have been fined Rs 20 crore and Rs 10 crore, respectively. The fine was imposed on Reliance India Limited because the company violated the Prohibition of Fraudulent and Unfair Trade Practices (PFUTP). 4. International card payment service RuPay partnered partnered with RBL Bank to launch an innovative payment solution for Indian merchants “RuPay PoS” in association with PayNearby. -

19. CD-ROM Games

Forthcoming in WOLF, Mark J.P. (ed.). Video Game History: From Bouncing Blocks to a Global Industry, Greenwood Press, Westport, Conn. 19. CD-ROM Games Carl Therrien While it became a standard relatively recently, disc-based storage goes a long way back in the history of video game distribution. The term encompasses a wide range of technologies, from magnetic floppy discs, analog laserdiscs, to a variety of digital optical media. Of the latter, the CD-ROM enjoyed the strongest following and the longest lifespan; as of 2006, a significant number of PC games are still burned on CDs. When it became the most common video game distribution format in the mid nineteen-nineties, the compact disc was already a standard in the music industry. In contrast to the magnetic tapes used for the distribution of albums and movies, optical discs allowed relatively fast, random, non-linear access to the content. But these features were already common in the realm of cartridge-based video game systems; the ROMs in Atari 2600 or Super Nintendo game cartridges were directly connected to the system’s working memory and could be read instantly. The CD drive optical head couldn’t compete; as a matter of fact, optical discs introduced the infamous “loading” screen to the console gamer. Video games benefited first and foremost from the storage capabilities of the CD-ROM. While the CD format shares its core technical principle with the more recent DVD standard (found in the Xbox and PlayStation 2) and other dedicated formats (such as the Dreamcast’s GD-ROM and the Gamecube optical disc), this chapter will focus solely on the integration of CD-ROM technology and its consequences on game design and development. -

Oracle® Multimedia Reference

Oracle® Multimedia Reference 18c E84256-02 August 2018 Oracle Multimedia Reference, 18c E84256-02 Copyright © 1999, 2018, Oracle and/or its affiliates. All rights reserved. Primary Author: Lavanya Jayapalan Contributors: Sue Pelski, Melliyal Annamalai, Susan Mavris, James Steiner This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, delivered to U.S. Government end users are "commercial computer software" pursuant to the applicable Federal Acquisition Regulation and agency- specific supplemental regulations. As such, use, duplication, disclosure, modification, and adaptation of the programs, including any operating system, integrated software, any programs installed on the hardware, and/or documentation, shall be subject to license terms and license restrictions applicable to the programs. -

Company Backgrounders : Fiji

Company Backgrounder by Dataquest Fuji Electric Co., Ltd. 12-1 Yurakucho 1-chome, Chyoda-ku Tokyo 100, Japan Telephone: Tokyo 211-7111 Telex: J22331 FUJIELEA or FUJIELEB Fax: (03) 215-8321 Dun's Number: 05-667-2785 Date Founded: 1923 CORPORATE STRATEGIC DIRECTION silicon diodes, thyristors, application-specific ICs (ASICs), LSIs, hybrid ICs, surge absorbers, semicon ductors, sensors, photoconductive drums for copiers, Since its founding in 1923, Fuji Electric Co., Ltd., has been supplying high-quality products to a wide printers, hard-disk drives, magnetic recording disks, variety of industries. Expanding outward while main and watt-hour meters. taining its base as a heavy electrical manufacturer, the Company has achieved leading market positions in Products in the Motors, Drives, and Controls Division products such as uninterruptible power supplies, include induction motors, variable-speed controlled inverters, high-voltage silicon diodes, and vending motors, brake and geared motors, pumps, fans and machines. blowers, inverters, servomotor systems, small preci sion motors, magnetic contractors, and molded case circuit breakers. This division accounted for Fuji Electric's business is organized into five divi 20.5 percent of total revenue, or ¥157.6 biUion sions: Heavy Electrical; Systems; Electronic Devices; (US$1.1 billion) for year ended March 1990. Motors, Drives, and Controls; and Vending Machines and Specialty Appliances. The Heavy Electrical Division manufactures ttieimal power plant equip The Vending Machines and Specialty Appliances ment, hydroelectric power plant equipment, nuclear Division accounted for 17.4 percent of revenue, total power plant equipment, electric motors, transformers, ing ¥133.7 billion (US$938.7 million) for fiscal year computer control equipment, and odier heavy electri ended March 1990. -

Table of Contents

2 English Table of Contents Usage Notice Precautions ............................................................................................. 3 Introduction About the Product .................................................................................... 4 Package Overview .................................................................................. 5 Installation Product Overview .................................................................................... 6 Start Your Installation............................................................................... 8 User Controls User Control Overview ............................................................................ 10 Function Descriptions.............................................................................. 13 Appendices Troubleshooting ....................................................................................... 16 The Apple Macintosh Connections ......................................................... 18 Maintenance ............................................................................................ 19 Specifications .......................................................................................... 21 Compatibility Modes ................................................................................ 22 3 English Usage Notice Warning- Do not look into the lens. The bright light may hurt your eyes. Warning- To reduce the risk of fire or electric shock, do not expose this product to rain or moisture. Warning- Please do -

Oracle Intermedia Reference, 10G Release 2 (10.2) B14297-01

Oracle® interMedia Reference 10g Release 2 (10.2) B14297-01 June 2005 Oracle interMedia ("interMedia") is a feature that enables Oracle Database to store, manage, and retrieve images, audio, video, or other heterogeneous media data in an integrated fashion with other enterprise information. Oracle interMedia extends Oracle Database reliability, availability, and data management to multimedia content in Internet, electronic commerce, and media-rich applications. Oracle interMedia Reference, 10g Release 2 (10.2) B14297-01 Copyright © 1999, 2005, Oracle. All rights reserved. Primary Author: Sue Pelski Contributors: Robert Abbott, Sanjay Agarwal, Melli Annamalai, Bill Beauregard, Raja Chatterjee, Fengting Chen, Rajiv Chopra, Helen Grembowicz, Dongbai Guo, Susan Kotsovolos, Andrew Lamb, Albert Landeck, Dong Lin, Joseph Mauro, Susan Mavris, Rabah Mediouni, Simon Oxbury, Vishal Rao, Todd Rowell, Susan Shepard, Ingrid Stuart, Rosanne Toohey, Bill Voss, Rod Ward, Manjari Yalavarthy The Programs (which include both the software and documentation) contain proprietary information; they are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are also protected by copyright, patent, and other intellectual and industrial property laws. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of the Programs, except to the extent required to obtain interoperability with other independently created software or as specified by law, is prohibited. The information contained in this document is subject to change without notice. If you find any problems in the documentation, please report them to us in writing. This document is not warranted to be error-free. Except as may be expressly permitted in your license agreement for these Programs, no part of these Programs may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, for any purpose. -

European Semiconductor Industry Service (ESIS) Have Received This Data As a Loose-Leaf Service Section to Be Filed in Their Binder Set

DataQuest a company of MThe Dun & Bradstreet Corporation 7th April Dear Client, NEW FORMAT—MARKET SHARE DATA Dataquest's Eviropean Components Group completed preliminary 1988 European semiconductor market share estimates, which are enclosed herein. In the past, clients of the European Semiconductor Industry Service (ESIS) have received this data as a loose-leaf service section to be filed in their binder set. For your convenience we are now publishing this data in the form of a booklet. This booklet can still be filed as before, but offers much greater ease of use "on the move". We have also presented the market share estimates in a ranked format, rather than in alphabetical format, for your ease in comparing of vendors' market positions in different products and technologies. The previous year's rank is also shown for reference. Extra analysis is given, such as percentage market share for each vendor, for further ease in interpreting the estimates. We hope this helps make our estimates more usefuL to you. We would be interested in your comments regarding this new format. Yours sincerely %Y^^ • Bypon Harding Research Analyst European Components Group. 1290 Ridder Park Drive, San Jose, CA 95131-2398 (408) 437-8000 Telex 171973 Fax (408) 437-0292 European Semiconductor Industry Service Volume III—Companies E)ataQuest nn acompanyof IISI TheDun&Biadstreetcorporation 12^ Ridder Park Drive San Jose, California 95131-2398 (408) 437-8000 Telex: 171973 I^: (408) 437-0292 Sales/Service Offices: UNITED KINGDOM FRANCE EASTERN U.S. Dataquest Europe Limited Dataquest Europe SA Dataquest Boston Roussel House, Tour Gallieni 2 1740 Massachusetts Ave. -

Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade

Edited by Virtual water trade A.Y. Hoekstra February 2003 Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade IHE Delft, The Netherlands 12-13 December 2002 Value of Water Research Report Series No. 12 Virtual water trade Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade Edited by A.Y. Hoekstra February 2003 Value of Water Research Report Series No. 12 IHE Delft P.O. Box 3015 2601 DA Delft The Netherlands Preface This report results from the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade that was held at IHE Delft, the Netherlands, 12-13 December 2002. The aim of the Expert Meeting was to exchange scientific knowledge on the subject of Virtual Water Trade, to review the state-of-the-art in this field of expertise, to discuss in-depth the various aspects relevant to the subject and to set the agenda for future research. In particular the meeting was used as a preparatory meeting to the Session on ‘Virtual Water Trade and Geopolitics’ to take place at the Third World Water Forum in Japan, March 2003. The expert meeting in Delft was the first meeting in a series of meetings organised in the framework of phase VI of the International Hydrological Programme (IHP) of UNESCO and WMO. The meetings fit in the programme ‘Water Interactions: Systems at Risk and Social Challenges’, in particular Focal Area 2.4 ‘Methodologies for Integrated River Basin Management’ and Focal Area 4.2 ‘Value of Water’. The series is organised under the auspices of the Dutch and German IHP Committees and the International Water Assessment Centre (IWAC). -

1900 (Parents: 769, Clones: 1131)

Supported systems: 1900 (parents: 769, clones: 1131) Description [ ] Name [ ] Parent [ ] Year [ ] Manufacturer [ ] Sourcefile [ ] 1200 Micro Computer shmc1200 studio2 1978 Sheen studio2.c (Australia) 1292 Advanced Programmable Video 1292apvs 1976 Radofin vc4000.c System 1392 Advanced Programmable Video 1392apvs 1292apvs 1976 Radofin vc4000.c System 15IE-00-013 ie15 1980 USSR ie15.c 286i k286i ibm5170 1985 Kaypro at.c 3B1 3b1 1985 AT&T unixpc.c 3DO (NTSC) 3do 1991 The 3DO Company 3do.c 3DO (PAL) 3do_pal 3do 1991 The 3DO Company 3do.c 3DO M2 3do_m2 199? 3DO konamim2.c 4004 Nixie Clock 4004clk 2008 John L. Weinrich 4004clk.c 486-PIO-2 ficpio2 ibm5170 1995 FIC at.c 4D/PI (R2000, 20MHz) sgi_ip6 1988 Silicon Graphics Inc sgi_ip6.c 6809 Portable d6809 1983 Dunfield d6809.c 68k Single Board 68ksbc 2002 Ichit Sirichote 68ksbc.c Computer 79152pc m79152pc ???? Mera-Elzab m79152pc.c 800 Junior elwro800 1986 Elwro elwro800.c 9016 Telespiel mtc9016 studio2 1978 Mustang studio2.c Computer (Germany) A5120 a5120 1982 VEB Robotron a51xx.c A5130 a5130 a5120 1983 VEB Robotron a51xx.c A7150 a7150 1986 VEB Robotron a7150.c Aamber Pegasus pegasus 1981 Technosys pegasus.c Aamber Pegasus with pegasusm pegasus 1981 Technosys pegasus.c RAM expansion unit ABC 1600 abc1600 1985 Luxor abc1600.c ABC 80 abc80 1978 Luxor Datorer AB abc80.c ABC 800 C/HR abc800c 1981 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 800 M/HR abc800m abc800c 1981 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 802 abc802 1983 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c ABC 806 abc806 1983 Luxor Datorer AB abc80x.c Acorn Electron electron 1983 -

DOS/V and Japan's PC Market

Strategic Management Society 16th Annual International Conference Phoenix, Arizona November 12, 1996 Competing through Standards: DOS/V and Japan’s PC Market Joel West <[email protected]> and Jason Dedrick <[email protected]> Center for Research on Information Technologies and Organizations (CRITO) University of California, Irvine 3200 Berkeley Place Irvine, CA 92697-4650 +1-714-824-5449; fax: +1-714-824-8091 http://www.crito.uci.edu November 30, 1996 Working Paper: #PAC-111 Contents The Race to Establish a Dominant Standard.............................. 2 Advantages of Successful Standards.................................... 3 Technological Discontinuities and Dominant Design............ 4 Pioneer Advantages and Disadvantages............................... 5 Heuristics for Establishing Dominant Standards................... 7 Japanese PCs in the 1980’s: PC-98 as the Dominant Standard... 8 Global Dominant Design: IBM PC ...................................... 8 Japanese PC Industry: High Barriers to Entry...................... 9 Japan’s Dominant Design: NEC PC-9801............................ 11 Market Positions, 1991 ....................................................... 13 The DOS/V Revolution ............................................................ 14 Development of the DOS/V Standard.................................. 14 Transforming the Marketplace, 1991-1995.......................... 15 Results of the DOS/V Revolution........................................ 18 Lessons and Implications ......................................................... -

Topics in Access, Storage, and Sensor Networks

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2010 Topics in access, storage, and sensor networks Swapnil Bhatia University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Bhatia, Swapnil, "Topics in access, storage, and sensor networks" (2010). Doctoral Dissertations. 582. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/582 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOPICS IN ACCESS, STORAGE, AND SENSOR NETWORKS BY Swapnil Bhatia Bachelor of Computer Engineering, Mumbai University (1999) DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science May 2010 UMI Number: 3470089 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI' Dissertation Publishing UMI 3470089 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. uestA ® ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 This dissertation has been examined and approved. -

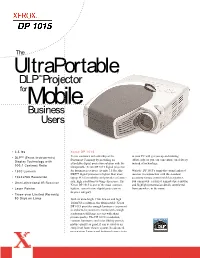

Ultraportable, DLP™ Projector Formobile Business Users

The UltraPortable, DLP™ Projector forMobile Business Users • 3.5 lbs Xerox DP 1015 • DLP™ (Texas Instruments) Xerox continues its leadership as the to your PC will get you up and running Document Company by providing an effortlessly, so you can concentrate on delivery Display Technology with affordable digital projection solution with the instead of technology. 900:1 Contrast Ratio ultraportable Xerox DP 1015 digital projector • 1500 Lumens for business presenters. At only 3.5 lbs, this With the DP 1015’s omni-directional infrared DLP™ digital projector is lighter than most receiver in conjunction with the standard • 1024x768 Resolution laptop PCs for mobility and provides a feature- accessory remote control with laser pointer, rich, high resolution viewing experience. The you can provide a relaxed, animated presentation • Omni-directional IR Receiver Xerox DP 1015 is one of the most compact, and highlight presentation details untethered • Laser Pointer lightest, easiest to use digital projectors in from anywhere in the room. its price category. • Three-year Limited Warranty, 90 Days on Lamp With its ultra-bright 1500 lumens and high 1024x768 resolution, the ultraportable Xerox DP 1015 provides enough luminance to present in ambient-lit conference rooms with enough resolution to fill large screens with sharp picture quality. The DP 1015’s resolution, contrast, luminance and color fidelity provide picture quality so good, it can be used as an entry-level home theater system. Its advanced presentation features and foolproof connectivity Features and Benefits DLP™ (Texas Instruments) Xerox DP 1015 Digital Projector Specifications Display Technology The DP 1015’s powerful DLP technology pro- Projector Type Single 0.7-inch DLP technology from Texas Instruments duces a contrast ratio of 900:1, which provides Weight/Dimensions 3.5 lb, 9.0(W) x 7.6(D) x 2.7(H) inches; 229(W) x 193(D) x 69 (H) mm truer blacks and holds highlight detail for Resolution Native: 1024 x 768 XGA unsurpassed picture clarity, luminance and Brightness 1500 Lumens color accuracy.