Why Ekphrasis? Author(S): Valentine Cunningham Source: Classical Philology, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frick Collection, New York Works from the Permanent Collection

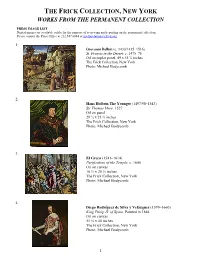

THE FRICK COLLECTION, NEW YORK WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available solely for the purpose of reviewing and reporting on the permanent collection. Please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430/1435–1516) St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1475–78 Oil on poplar panel, 49 x 55 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2. Hans Holbein The Younger (1497/98–1543) Sir Thomas More, 1527 Oil on panel 29 ½ x 23 ¾ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3. El Greco (1541–1614) Purification of the Temple, c. 1600 Oil on canvas 16 ½ x 20 ⅝ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 4. Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) King Philip IV of Spain, Painted in 1644 Oil on canvas 51 ⅛ x 40 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 1 5. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657 Oil on canvas 19 ⅞ x 18 ⅛ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 6. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Self-Portrait, dated 1658 Oil on canvas 52 ⅝ x 40 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 7. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) The Rehearsal, 1878–79 Oil on canvas 18 ¾ x 24 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 8. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) The Meeting (one panel in the series called The Progress of Love), 1771–73 Oil on canvas 125 x 96 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2 9. -

Modernist Ekphrasis and Museum Politics

1 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2017 2 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2017 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the public art museum and its practices of collecting, organizing, and defining cultures at once enabled and constrained the poetic forms and subjects available to American and British poets of a transatlantic long modernist period. I trace these lines of influence particularly as they shape modernist engagements with ekphrasis, the historical genre of poetry that describes, contemplates, or interrogates a visual art object. Drawing on a range of materials and theoretical formations—from archival documents that attest to modernist poets’ lived experiences in museums and galleries to Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology of art and critical scholarship in the field of Museum Studies—I situate modernist ekphrastic poetry in relation to developments in twentieth-century museology and to the revolutionary literary and visual aesthetics of early twentieth-century modernism. This juxtaposition reveals how modern poets revised the conventions of, and recalibrated the expectations for, ekphrastic poetry to evaluate the museum’s cultural capital and its then common marginalization of the art and experiences of female subjects, queer subjects, and subjects of color. -

Alex Katz Coca Cola Press Release

Alex Katz Coca-Cola Girls 2 November – 21 December, 2018 Timothy Taylor, London, is pleased to present Coca-Cola Girls, an exhibition of new large-scale paintings by Alex Katz inspired by the eponymous, and iconic, figures from advertising art history. The Coca-Cola Girls were an integral component of the company’s advertising from the 1890’s through to the 1960’s, emanating an ideal of the American woman. Initially, the Coca-Cola Girls were reserved and demure, evolving during WWI, and through the era of the pin-up, to images of empowered service women in uniform, and athletic, care-free, women at leisure. In the context of pre-televised advertising, the wall decals and large-scale billboards depicting these figures made a significant impact on the visual language of the American urban landscape. For Katz, this optimistic figure also encapsulates a valuable notion of nostalgia; “That’s Coca-Cola red, from the company’s outdoor signs in the fifties… you know, the blond girl in the red convertible, laughing with unlimited happiness. It’s a romance image, and for me it has to do with Rembrandt’s ‘The Polish Rider.’ I could never understand that painting but my mother and Frank O’Hara both flipped over it, so I realized I was missing something. They saw it as a romantic figure, riding from the Black Sea to the Baltic.” 1 . The poses captured in these new paintings disclose a sense of balletic movement; a left arm extending upwards, a head twisted to the right, a leg poised on the ball of a foot, or a hand extending to and from nowhere - always glimpsed in a fleeting gesture within a dynamic sequence. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies Teaching English Language and Literature for Secondary Schools Miriam Zbíralová Faith and Religion in Selected Novels by Iris Murdoch Master‟s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Prof. Mgr. Milada Franková, CSc., M.A. 2012 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author‟s signature Acknowledgement: I would like to thank my supervisor, prof. Franková, for valuable advice and constant support during the whole process of writing the thesis. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 5 1 Religion and Morality .................................................................................................... 7 1.1 The Nature of Good and Morality .......................................................................... 7 1.2 God and Good ....................................................................................................... 17 1.3 Morality without Religion .................................................................................... 22 2 Religion, Morality and Art ........................................................................................... 31 2.1 Art and Morality ................................................................................................... 31 2.2 Art and Religion ................................................................................................... -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt

Originalveröffentlichung in: Artibus et Historiae 21 (2000), Nr. 41, S. 197-205 ZDZISLAW ZYGULSKI, JR. Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt Few paintings included among outstanding creations of chaser was an outstanding American collector, Henry Clay modern painting provoke as many disputes, polemics and Frick, king of coke and steel who resided in Pittsburgh and passionate discussions as Rembrandt's famous Lisowczyk, since 1920 in New York where, in a specially designed build 1 3 which is known abroad as the Polish Rider . The painting was ing, he opened an amazingly beautiful gallery . The transac purchased by Michat Kazimierz Ogihski, the grand hetman of tion, which arouse public indignation in Poland, was carried Lithuania in the Netherlands in 1791 and given to King out through Roger Fry, a writer, painter and art critic who occa Stanislaus Augustus in exchange for a collection of 420 sionally acted as a buyer of pictures. The price including his 2 guldens' worth of orange trees . It was added to the royal col commission amounted to 60,000 English pounds, that was lection in the Lazienki Palace and listed in the inventory in a little above 300,000 dollars, but not half a million as was 1793 as a "Cosaque a cheval" with the dimensions 44 x 54 rumoured in Poland later. inch i.e. 109,1 x 133,9 cm and price 180 ducats. In his letter to the King, Hetman Ogihski called the rider, The subsequent history of the painting is well known. In presented in the painting "a Cossack on horseback". -

HNA Apr 2015 Cover.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 32, No. 1 April 2015 Peter Paul Rubens, Agrippina and Germanicus, c. 1614, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1963.8.1. Exhibited at the Academy Art Museum, Easton, MD, April 25 – July 5, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Obituary/Tributes ................................................................. 1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) HNA News ............................................................................7 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Personalia ............................................................................... 8 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ........................................................................... -

Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920S Spain

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2015 Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920s Spain Brian M. Cole University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Cole, Brian M., "Ekphrasis and Avant-Garde Prose of 1920s Spain" (2015). Theses and Dissertations-- Hispanic Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/23 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Melania G. Mazzucco

Mamoli Zorzi and Manthorne (eds.) FROM DARKNESS TO LIGHT WRITERS IN MUSEUMS 1798-1898 Edited by Rosella Mamoli Zorzi and Katherine Manthorne From Darkness to Light explores from a variety of angles the subject of museum ligh� ng in exhibi� on spaces in America, Japan, and Western Europe throughout the nineteenth and twen� eth centuries. Wri� en by an array of interna� onal experts, these collected essays gather perspec� ves from a diverse range of cultural sensibili� es. From sensi� ve discussions of Tintore� o’s unique approach to the play of light and darkness as exhibited in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco in Venice, to the development of museum ligh� ng as part of Japanese ar� s� c self-fashioning, via the story of an epic American pain� ng on tour, museum illumina� on in the work of Henry James, and ligh� ng altera� ons at Chatsworth, this book is a treasure trove of illumina� ng contribu� ons. FROM DARKNESS TO LIGHT FROM DARKNESS TO LIGHT The collec� on is at once a refreshing insight for the enthusias� c museum-goer, who is brought to an awareness of the exhibit in its immediate environment, and a wide-ranging scholarly compendium for the professional who seeks to WRITERS IN MUSEUMS 1798-1898 proceed in their academic or curatorial work with a more enlightened sense of the lighted space. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. Printed and digital edi� ons, together with supplementary digital material, can also be found at www.openbookpublishers.com Cover image: -

Vii. Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-69)

VII. REMBRANDT VAN RIJN (1606-69) Biographical and background information 1. Rembrandt born in Leiden, son of a prosperous miller; settled in Amsterdam in 1632. 2. Married Saskia van Uylenburgh in 1634, who died in 1642; living with Hendrickje Stoffels by 1649. 3. Declaration of bankruptcy in 1656 and auctions of his property in 1657 and 1658; survived Hendrickje (d. 1663) and his son Titus (1641-68). 4. Dutch cultural and political background: war of liberation from Catholic Spain (1568-1648) and Protestant dominance; Dutch commerce and maritime empire. 5. Oil medium: impasto, glazes, canvas support, chiaroscuro and color. Selected works 6. Religious subjects a. Supper at Emmaus, c. 1628-30 (oil on panel, 1’3” x 1’5”, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris) b. Blinding of Samson, 1636 (oil on canvas, 7’9” x 9’11”, Städelshes Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt-am-Main) c. Supper at Emmaus, 1648 (oil on panel, 2’3” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) d. Return of the Prodigal Son, c. 1668-69 (oil on canvas, 8’7” x 2’7”, The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) 7. Self-Portraits—appearance, identity, image of the artist a. Self-portrait, 1629 (oil on panel, 9 ¼” x 6 ¾”, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Kassel) b. Self-portrait, c. 1634 (oil on panel, 26 ½” x 21 ¼”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) c. Self-portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill, 1639 (etching, 8” x 6 ½”) d. Self-portrait, 1640 (oil on panel, 1’10” x 1’7”, National Gallery, London) i. Comparisons 1. Raphael, Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514- 15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) 2. -

Complete List — 1 Foreword

2019/2020 Complete List — 1 Foreword Chaos and Awe – are these the words that best sum up our teenage 21st century? They also happen to be the title of the Chrysler Museum’s latest exhibition on painting in the 21st century, whose artworks invoke the 18th-century philosophical notion of the sublime. In the 18th century this specifically related to the sense of being overwhelmed by the immeasurable nature of God and the physical world. To a 21st-century, largely atheist audience, such a concept might likely conjure up the powerful, exciting and destabilizing effects of globalization, mass migration, radical ideologies and the rapid growth of technology in our lives; that sense of our being overwhelmed by competing forces in our daily world. Or perhaps, it might just evoke a sense of “zoning-out”; that in the face of so much depressing news, misinformation, and hyper-sensitising technology, simply ignoring the world around us is the easiest way to maintain some semblance of normality – the path of non-resistance so to speak. So how do we engage meaningfully in today’s world in ways that do not engender anxiety, fear, conflict, or an overriding sense of impotent fury? Well here’s a thought; the next time you find yourself in a town or city which has a museum, or an art gallery, or just a library, simply step inside and go and look at a work of art – any work of art – for ten minutes. It could be a painting, an installation, a wonderful object, or a beautifully designed and printed book. -

Ekphrastic Poetry

Art and Poetry Background Information Ekphrastic Poetry Ekphrastic poetry has come to be defined as poems written about works of art; however, in ancient Greece, the ekphrasi term s was applied to the skill of describing a thing with vivid detail. One of the earliest examples of ekphrasis can be found ’ in Homer s epic poem The Iliad, in which the speaker elaborately describes the shield of Achilles in nearly 150 poetic lines: And first Hephaestus makes a great and massive shield, blazoning well-‐wrought emblems all across its surface, … And he forged on the shield two noble cities filled with mortal men. With weddings and wedding feasts in one … And he forged the Ocean River’s mighty power girdling round the outmost rim of the welded indestructible shield. (The Iliad, Book 18, lines – 558 707) In addition to the descriptions of a work of art, an ekphrastic poem usually includes an exploration of how the speaker is impacted by his or her experience with John the work. For example, in Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the ancient vessel piques the curiosity of the speaker, who asks: “What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?” Poetic Responses to Art It is not uncommon r fo writers to have transformative experiences with works of art. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke was greatly influenced by visual art, including the paintings of the French artist Paul Cezanne, whose work, he believed, helped his writing. Rilke captures the transformative experience of viewing a work of art in his poem Archaic “ Torso of Apollo.” In the poem, the speaker’s observations about an ancient sculpture spark reflections about existence.