163 JAN BIALOSTOCKI Rembrandt's 'Eques Polonus'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frick Collection, New York Works from the Permanent Collection

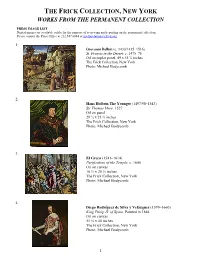

THE FRICK COLLECTION, NEW YORK WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available solely for the purpose of reviewing and reporting on the permanent collection. Please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430/1435–1516) St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1475–78 Oil on poplar panel, 49 x 55 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2. Hans Holbein The Younger (1497/98–1543) Sir Thomas More, 1527 Oil on panel 29 ½ x 23 ¾ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3. El Greco (1541–1614) Purification of the Temple, c. 1600 Oil on canvas 16 ½ x 20 ⅝ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 4. Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) King Philip IV of Spain, Painted in 1644 Oil on canvas 51 ⅛ x 40 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 1 5. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657 Oil on canvas 19 ⅞ x 18 ⅛ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 6. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Self-Portrait, dated 1658 Oil on canvas 52 ⅝ x 40 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 7. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) The Rehearsal, 1878–79 Oil on canvas 18 ¾ x 24 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 8. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) The Meeting (one panel in the series called The Progress of Love), 1771–73 Oil on canvas 125 x 96 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2 9. -

Alex Katz Coca Cola Press Release

Alex Katz Coca-Cola Girls 2 November – 21 December, 2018 Timothy Taylor, London, is pleased to present Coca-Cola Girls, an exhibition of new large-scale paintings by Alex Katz inspired by the eponymous, and iconic, figures from advertising art history. The Coca-Cola Girls were an integral component of the company’s advertising from the 1890’s through to the 1960’s, emanating an ideal of the American woman. Initially, the Coca-Cola Girls were reserved and demure, evolving during WWI, and through the era of the pin-up, to images of empowered service women in uniform, and athletic, care-free, women at leisure. In the context of pre-televised advertising, the wall decals and large-scale billboards depicting these figures made a significant impact on the visual language of the American urban landscape. For Katz, this optimistic figure also encapsulates a valuable notion of nostalgia; “That’s Coca-Cola red, from the company’s outdoor signs in the fifties… you know, the blond girl in the red convertible, laughing with unlimited happiness. It’s a romance image, and for me it has to do with Rembrandt’s ‘The Polish Rider.’ I could never understand that painting but my mother and Frank O’Hara both flipped over it, so I realized I was missing something. They saw it as a romantic figure, riding from the Black Sea to the Baltic.” 1 . The poses captured in these new paintings disclose a sense of balletic movement; a left arm extending upwards, a head twisted to the right, a leg poised on the ball of a foot, or a hand extending to and from nowhere - always glimpsed in a fleeting gesture within a dynamic sequence. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt

Originalveröffentlichung in: Artibus et Historiae 21 (2000), Nr. 41, S. 197-205 ZDZISLAW ZYGULSKI, JR. Further Battles for the Lisowczyk (Polish Rider) by Rembrandt Few paintings included among outstanding creations of chaser was an outstanding American collector, Henry Clay modern painting provoke as many disputes, polemics and Frick, king of coke and steel who resided in Pittsburgh and passionate discussions as Rembrandt's famous Lisowczyk, since 1920 in New York where, in a specially designed build 1 3 which is known abroad as the Polish Rider . The painting was ing, he opened an amazingly beautiful gallery . The transac purchased by Michat Kazimierz Ogihski, the grand hetman of tion, which arouse public indignation in Poland, was carried Lithuania in the Netherlands in 1791 and given to King out through Roger Fry, a writer, painter and art critic who occa Stanislaus Augustus in exchange for a collection of 420 sionally acted as a buyer of pictures. The price including his 2 guldens' worth of orange trees . It was added to the royal col commission amounted to 60,000 English pounds, that was lection in the Lazienki Palace and listed in the inventory in a little above 300,000 dollars, but not half a million as was 1793 as a "Cosaque a cheval" with the dimensions 44 x 54 rumoured in Poland later. inch i.e. 109,1 x 133,9 cm and price 180 ducats. In his letter to the King, Hetman Ogihski called the rider, The subsequent history of the painting is well known. In presented in the painting "a Cossack on horseback". -

HNA Apr 2015 Cover.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 32, No. 1 April 2015 Peter Paul Rubens, Agrippina and Germanicus, c. 1614, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1963.8.1. Exhibited at the Academy Art Museum, Easton, MD, April 25 – July 5, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Obituary/Tributes ................................................................. 1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) HNA News ............................................................................7 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Personalia ............................................................................... 8 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ........................................................................... -

Vii. Rembrandt Van Rijn (1606-69)

VII. REMBRANDT VAN RIJN (1606-69) Biographical and background information 1. Rembrandt born in Leiden, son of a prosperous miller; settled in Amsterdam in 1632. 2. Married Saskia van Uylenburgh in 1634, who died in 1642; living with Hendrickje Stoffels by 1649. 3. Declaration of bankruptcy in 1656 and auctions of his property in 1657 and 1658; survived Hendrickje (d. 1663) and his son Titus (1641-68). 4. Dutch cultural and political background: war of liberation from Catholic Spain (1568-1648) and Protestant dominance; Dutch commerce and maritime empire. 5. Oil medium: impasto, glazes, canvas support, chiaroscuro and color. Selected works 6. Religious subjects a. Supper at Emmaus, c. 1628-30 (oil on panel, 1’3” x 1’5”, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris) b. Blinding of Samson, 1636 (oil on canvas, 7’9” x 9’11”, Städelshes Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt-am-Main) c. Supper at Emmaus, 1648 (oil on panel, 2’3” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) d. Return of the Prodigal Son, c. 1668-69 (oil on canvas, 8’7” x 2’7”, The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg) 7. Self-Portraits—appearance, identity, image of the artist a. Self-portrait, 1629 (oil on panel, 9 ¼” x 6 ¾”, Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen, Kassel) b. Self-portrait, c. 1634 (oil on panel, 26 ½” x 21 ¼”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) c. Self-portrait Leaning on a Stone Sill, 1639 (etching, 8” x 6 ½”) d. Self-portrait, 1640 (oil on panel, 1’10” x 1’7”, National Gallery, London) i. Comparisons 1. Raphael, Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514- 15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) 2. -

Complete List — 1 Foreword

2019/2020 Complete List — 1 Foreword Chaos and Awe – are these the words that best sum up our teenage 21st century? They also happen to be the title of the Chrysler Museum’s latest exhibition on painting in the 21st century, whose artworks invoke the 18th-century philosophical notion of the sublime. In the 18th century this specifically related to the sense of being overwhelmed by the immeasurable nature of God and the physical world. To a 21st-century, largely atheist audience, such a concept might likely conjure up the powerful, exciting and destabilizing effects of globalization, mass migration, radical ideologies and the rapid growth of technology in our lives; that sense of our being overwhelmed by competing forces in our daily world. Or perhaps, it might just evoke a sense of “zoning-out”; that in the face of so much depressing news, misinformation, and hyper-sensitising technology, simply ignoring the world around us is the easiest way to maintain some semblance of normality – the path of non-resistance so to speak. So how do we engage meaningfully in today’s world in ways that do not engender anxiety, fear, conflict, or an overriding sense of impotent fury? Well here’s a thought; the next time you find yourself in a town or city which has a museum, or an art gallery, or just a library, simply step inside and go and look at a work of art – any work of art – for ten minutes. It could be a painting, an installation, a wonderful object, or a beautifully designed and printed book. -

Oral History Center University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Joyce Hill Stoner Joyce Hill Stoner: My Life in Art Conservation and Intersections with the Getty Getty Trust Oral History Project Interviews conducted by Amanda Tewes in 2019 Interviews sponsored by the J. Paul Getty Trust Copyright © 2020 by J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of The Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. -

Why Ekphrasis? Author(S): Valentine Cunningham Source: Classical Philology, Vol

Why Ekphrasis? Author(s): Valentine Cunningham Source: Classical Philology, Vol. 102, No. 1, Special Issues on Ekphrasis<break></break>Edited by Shadi Bartsch and Jaś Elsner (January 2007), pp. 57-71 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/521132 . Accessed: 27/05/2014 15:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Classical Philology. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.76.8.49 on Tue, 27 May 2014 15:49:01 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions WHY EKPHRASIS? valentine cunningham t is hard to imagine western literature, certainly the tradition of Hel- lenic/Roman/Christian/post-Christian literature, without what we can I call ekphrasis—that pausing, in some fashion, for thought before, and/ or about, some nonverbal work of art, or craft, a poiema without words, some more or less aestheticized made object, or set of made objects. This might be done by the poet, whose name we might or might not know, giving a whole poem over to such consideration, or stopping that action, the narrative flow of a longer work, to direct his gaze, his characters’ gaze, our gaze, for a while, at such a thing or things. -

JULIUS S. HELD PAPERS, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items INVENTORY OF THE JULIUS S. HELD PAPERS, ca. 1921-1999 Finding aid prepared by Isabella Zuralski The Getty Research Institute Research Library Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California 90049-1688 Phone: (310) 440-7390 Fax: (310) 440-7780 Email Requests: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/reference_form.html URL: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library ©2005 J. Paul Getty Trust INVENTORY OF THE JULIUS S. 990056 1 HELD PAPERS, ca. 1921-1999 INVENTORY OF THE JULIUS S. HELD PAPERS, ca. 1918-1999 Accession no. 990056 Finding aid prepared by Isabella Zuralski Getty Research Institute. Research Library Contact Information: The Getty Research Institute Research Library Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California 90049-1688 Phone: (310) 440-7390 Fax: (310) 440-7780 Email Requests: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/reference_form.html URL: http://www.getty.edu/research/conducting_research/library/ Processed by: Isabella Zuralski Date Completed: November 2004 Encoded by: Isabella Zuralski ©2005 J. Paul Getty Trust. Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Collection number: 990056 Creator: Held, Julius Samuel, 1905- Extent: 168 boxes (ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: Getty Research Institute Research Library Special Collections and Visual Resources 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, Calif. 90049-1688 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

To the Exhibition Catalogue

-the banishment of ... 48, 191, 191, 196, 236, 268, 299, Conus imperialis L. 416, 416 (fig. 112b) 300, 302, 306, ... waiting for Abraham 132, portrayal HOMER 134, 318, 378, 378 of ... 192, figure identified as ... 132, 191, 192 -Aristotle contemplating the bust of... 27, 28, 134, 171, HAID, Johann Gottfried 134 378, ... as painted by A. de Gelder 38, figure identified -prints by... as ... teaching his pupils 134, ... dictating to scribes Man in Armour (after Rembrandt) 134, 134 (fig. 15a), 318, 319, 378, 379,... reciting versus 326, 327, Portrait 136 of ... copy after late Hellinistic original, Boston 378, 378 Hairy War 128 (fig. 97a) HALL, Bernard 18 -books by... HALS, Frans (also Francis)18, 44, 149, 150, 153, 187, Odyssey 340, 440 200, 286, 322 HONTHORST, Gerrit van 126, 160, 214, 222, 284 -broad manner of ... 184 -paintings by... -paintings by... Violinist with a Glass Amsterdam 214, 214 (fig. 33a) The Evangelist Luke Odessa 162 HONTHORST, Willem van 284 The Evangelist Matthew Odessa 161, 162, 162 (fig. HOOCH, Carel de 110, 114 22b), 286 HOOCH, Pieter de 146, 279 Corporalship of Captain Reynier Reael and Lieutenant HOOFT, Pieter Cornelisz Cornelis Michiels Blaeuw (with Pieter Codde) -plays by... Amsterdam 150, 152 (fig. 19c), 153 Geeraerdt van Velsen 170 Married Couple in a Garden ( Isaac Massa and Beatrix HOOFT, W D van der Laan ) Haarlem 240 -plays by... Portrait of a Man Cambridge 183, 184, 184 (fig. 28c) Heden-daeghsche Verlooren Soon 396 Portrait of a Standing Man Edinburgh 150, 152 (fig. HOOGEWERFF G J 134, 378 19b), 153 HOOGH, de Portrait of a Woman Edinburgh 153 -collection of .. -

Second-Floor Installation Digital Images Are Available for Publicity

Second-Floor Installation Digital images are available for publicity purposes. Please contact the Communications & Marketing Department at [email protected]. 1. Room 1: Jean Barbet’s Angel, 1475, greets visitors on the second floor of Frick Madison, the temporary new home of The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 2. Room 2: Early Netherlandish painting (1440–1570) by Memling (foreground), Van Eyck, David, and others, as shown at Frick Madison by The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 3. Room 2: Portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger face off at Frick Madison: Sir Thomas More (left), 1527, oil on panel, and Thomas Cromwell (right), ca. 1532–33, oil on panel, The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 4. Room 2: At left, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Three Soldiers, 1568, oil on panel; at right, portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger face off at Frick Madison: Sir Thomas More (left), 1527, oil on panel, and Thomas Cromwell (right), ca. 1532–33, The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 5. Room 3: Dutch portraits by Frans Hals, with a view through to Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait, 1658, as shown at Frick Madison by The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 6. Room 4: Rembrandt’s Self-Portrait (left), 1658, and The Polish Rider (right), ca. 1655, as shown at Frick Madison by The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 7. Room 5: Three of the Frick’s eight portraits by Van Dyck, as shown at Frick Madison by The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 8. Room 6: Three paintings by Vermeer (from left, Girl Interrupted at Her Music, Mistress and Maid, and Officer and Laughing Girl) as shown at Frick Madison by The Frick Collection; photo: Joe Coscia 9.