Max Ernst : a Retrospective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Frick Collection, New York Works from the Permanent Collection

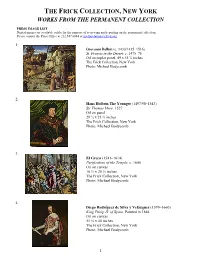

THE FRICK COLLECTION, NEW YORK WORKS FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION PRESS IMAGE LIST Digital images are available solely for the purpose of reviewing and reporting on the permanent collection. Please contact the Press Office at 212.547.6844 or [email protected]. 1. Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430/1435–1516) St. Francis in the Desert, c. 1475–78 Oil on poplar panel, 49 x 55 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2. Hans Holbein The Younger (1497/98–1543) Sir Thomas More, 1527 Oil on panel 29 ½ x 23 ¾ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 3. El Greco (1541–1614) Purification of the Temple, c. 1600 Oil on canvas 16 ½ x 20 ⅝ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 4. Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (1599–1660) King Philip IV of Spain, Painted in 1644 Oil on canvas 51 ⅛ x 40 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 1 5. Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675) Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657 Oil on canvas 19 ⅞ x 18 ⅛ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 6. Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn (1606–1669) Self-Portrait, dated 1658 Oil on canvas 52 ⅝ x 40 ⅞ inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 7. Hilaire-Germain-Edgar Degas (1834–1917) The Rehearsal, 1878–79 Oil on canvas 18 ¾ x 24 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 8. Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732–1806) The Meeting (one panel in the series called The Progress of Love), 1771–73 Oil on canvas 125 x 96 inches The Frick Collection, New York Photo: Michael Bodycomb 2 9. -

Max Ernst Was a German-Born Surrealist Who Helped Shape the Emergence of Abstract Expressionism in America Post-World War II

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Max Ernst was a German-born Surrealist who helped shape the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in America post-World War II. Armed with an academic understanding of Freud, Ernst often turned to his work-whether sculpture, painting, or collage-as a means of processing his experience in World War I and unpacking his feelings of dispossession in its wake. Key Ideas / Information • Ernst's work relied on spontaneity (juxtapositions of materials and imagery) and subjectivity (inspired by his personal experiences), two creative ideals that came to define Abstract Expressionism. • Although Ernst's works are predominantly figurative, his unique artistic techniques inject a measure of abstractness into the texture of his work. • The work of Max Ernst was very important in the nascent Abstract Expressionist movement in New York, particularly for Jackson Pollock. DETAILED VIEW: Childhood © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org Max Ernst was born into a middle-class family of nine children on April 2, 1891 in Brühl, Germany, near Cologne. Ernst first learned painting from his father, a teacher with an avid interest in academic painting. Other than this introduction to amateur painting at home, Ernst never received any formal training in the arts and forged his own artistic techniques in a self-taught manner instead. After completing his studies in philosophy and psychology at the University of Bonn in 1914, Ernst spent four years in the German army, serving on both the Western and Eastern fronts. Early Training The horrors of World War I had a profound and lasting impact on both the subject matter and visual texture of the burgeoning artist, who mined his personal experiences to depict absurd and apocalyptic scenes. -

Art on the Page

Art on the page Toward a modern illustrated book When Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard issued his first publication, Parallèlement, in 1900, a collection of poems by Paul Verlaine illustrated with lithographs by Impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard, he ushered in a new form of illustrated book to mark the new century. In the following decades, he and other entrepreneurial art publishers such as Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler and Albert Skira would take advantage of a widening pool of book collectors interested in modern art by producing deluxe books that featured original prints by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, André Derain and others. These books are generally referred to as livres des artistes and, unlike the fine press publications produced by the Kelmscott Press, the Doves Press or Ashendene Press, the earliest examples were distinguished by their modernity. Breon Mitchell, in his introduction to Beyond illustration, argues that the livre d’artiste can be differentiated from the traditional book in several respects: The illustrations are, in each case, original works of art (woodcuts, lithographs, etchings, engravings) executed by the artist himself and printed under his supervision. The book thus contains original graphics of the kind which find their place on museum walls … The livre d’artiste is also defined by the stature of the artist. Virtually every major painter and sculptor of the twentieth century—Picasso, Braque, Ernst, Matisse, Kokoschka, Barlach, Miró, to name a few—has collaborated in the creation of one or more such works. In many cases, book illustration has occupied such an important place in the total oeuvre of the artist that no student of art history can safely ignore it. -

Alex Katz Coca Cola Press Release

Alex Katz Coca-Cola Girls 2 November – 21 December, 2018 Timothy Taylor, London, is pleased to present Coca-Cola Girls, an exhibition of new large-scale paintings by Alex Katz inspired by the eponymous, and iconic, figures from advertising art history. The Coca-Cola Girls were an integral component of the company’s advertising from the 1890’s through to the 1960’s, emanating an ideal of the American woman. Initially, the Coca-Cola Girls were reserved and demure, evolving during WWI, and through the era of the pin-up, to images of empowered service women in uniform, and athletic, care-free, women at leisure. In the context of pre-televised advertising, the wall decals and large-scale billboards depicting these figures made a significant impact on the visual language of the American urban landscape. For Katz, this optimistic figure also encapsulates a valuable notion of nostalgia; “That’s Coca-Cola red, from the company’s outdoor signs in the fifties… you know, the blond girl in the red convertible, laughing with unlimited happiness. It’s a romance image, and for me it has to do with Rembrandt’s ‘The Polish Rider.’ I could never understand that painting but my mother and Frank O’Hara both flipped over it, so I realized I was missing something. They saw it as a romantic figure, riding from the Black Sea to the Baltic.” 1 . The poses captured in these new paintings disclose a sense of balletic movement; a left arm extending upwards, a head twisted to the right, a leg poised on the ball of a foot, or a hand extending to and from nowhere - always glimpsed in a fleeting gesture within a dynamic sequence. -

The Nature Ofarp Live Text-78-87.Indd 78

modern painters modernpaintersAPRIL 2019 PHILIPP THE COLORS OF ZEN: A CONVERSATION WITH HSIAO CHIN FÜRHOFER EXPLAINS HIS INSPIRATION TOP 10 ART BOOKS KIM CHONG HAK: THE KOREAN VAN GOGH BLOUINARTINFO.COM APRIL APRIL BLOUINARTINFO.COM + TOP 10: CONTEMPORARY POETS TO READ IN 2019 2019 04_MP_COVER.indd 1 19/03/19 3:56 PM 04_MP_The nature ofArp_Live text-78-87.indd 78 © 2019 ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/VG BILD-KUNST, BONN / © JEAN ARP, BY SIAE 2019. PHOTO: KATHERINE DU TIEL/SFMOMA 19/03/19 4:59PM Jean (Hans) Arp, “Objects Arranged according to the Laws of Chance III,” 1931, oil on wood, 10 1/8 x 11 3/8 x 2 3/8 in., San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. THE NATURE OF ARP THE SCULPTOR REFUSED TO BE CATEGORIZED, AS AN ARTIST OR AS A HUMAN BEING, MAKING A RETROSPECTIVE AT THE GUGGENHEIM IN VENICE A PECULIAR CHALLENGE TO CURATE BY SARAH MOROZ BLOUINARTINFO.COM APRIL 2019 MODERN PAINTERS 79 04_MP_The nature of Arp_Live text-78-87.indd 79 19/03/19 4:59 PM pursue this matter without affiliations with Constructivism and knowing where I’m going,” Surrealism, 1930s-era sinuous sculptures, Jean Arp once said of his collaborative works with Sophie Taeuber- intuitive approach. “This is Arp (his wife, and an artist in her own the mystery: my hands talk right) and the work made from the après- “to themselves.I The dialogue is established guerre period up until his death in 1966. between the plaster and them as if I am Two Project Rooms adjacent to the absent, as if I am not necessary. -

The Art of Hans Arp After 1945

Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 Volume 2 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Stiftung Arp e. V. Papers Volume 2 The Art of Arp after 1945 Edited by Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger Table of Contents 10 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning 12 Foreword Jana Teuscher and Loretta Würtenberger 16 The Art of Hans Arp after 1945 An Introduction Maike Steinkamp 25 At the Threshold of a New Sculpture On the Development of Arp’s Sculptural Principles in the Threshold Sculptures Jan Giebel 41 On Forest Wheels and Forest Giants A Series of Sculptures by Hans Arp 1961 – 1964 Simona Martinoli 60 People are like Flies Hans Arp, Camille Bryen, and Abhumanism Isabelle Ewig 80 “Cher Maître” Lygia Clark and Hans Arp’s Concept of Concrete Art Heloisa Espada 88 Organic Form, Hapticity and Space as a Primary Being The Polish Neo-Avant-Garde and Hans Arp Marta Smolińska 108 Arp’s Mysticism Rudolf Suter 125 Arp’s “Moods” from Dada to Experimental Poetry The Late Poetry in Dialogue with the New Avant-Gardes Agathe Mareuge 139 Families of Mind — Families of Forms Hans Arp, Alvar Aalto, and a Case of Artistic Influence Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen 157 Movement — Space Arp & Architecture Dick van Gameren 174 Contributors 178 Photo Credits 9 Director’s Foreword Engelbert Büning Hans Arp’s late work after 1945 can only be understood in the context of the horrific three decades that preceded it. The First World War, the catastro- phe of the century, and the Second World War that followed shortly thereaf- ter, were finally over. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

Derek Sayer ANDRÉ BRETON and the MAGIC CAPITAL: an AGONY in SIX FITS 1 After Decades in Which the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group

Derek Sayer ANDRÉ BRETON AND THE MAGIC CAPITAL: AN AGONY IN SIX FITS 1 After decades in which the Czechoslovak Surrealist Group all but vanished from the art-historical record on both sides of the erstwhile Iron Curtain, interwar Prague’s standing as the “second city of surrealism” is in serious danger of becoming a truth universally acknowledged.1 Vítězslav Nezval denied that “Zvěrokruh” (Zodiac), which appeared at the end of 1930, was a surrealist magazine, but its contents, which included his translation of André Breton’s “Second Manifesto of Surrealism” (1929), suggested otherwise.2 Two years later the painters Jindřich Štyrský and Toyen (Marie Čermínová), the sculptor Vincenc Makovský, and several other Czech artists showed their work alongside Hans/Jean Arp, Salvador Dalí, Giorgio De Chirico, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Joan Miró, Wolfgang Paalen, and Yves Tanguy (not to men- tion a selection of anonymous “Negro sculptures”) in the “Poesie 1932” exhibition at the Mánes Gallery.3 Three times the size of “Newer Super-Realism” at the Wads- worth Atheneum the previous November – the first surrealist exhibition on Ameri- 1 Not one Czech artist was included, for example, in MoMA’s blockbuster 1968 exhibition “Dada, Surrealism, and Their Heritage” or discussed in William S. Rubin’s accompanying monograph “Dada and Surrealist Art” (New York 1968). – Recent western works that seek to correct this picture include Tippner, Anja: Die permanente Avantgarde? Surrealismus in Prag. Köln 2009; Spieler, Reinhard/Auer, Barbara (eds.): Gegen jede Vernunft: Surrealismus Paris-Prague. Ludwigshafen 2010; Anaut, Alberto (ed.): Praha, Paris, Barcelona: moderni- dad fotográfica de 1918 a 1948/Photographic Modernity from 1918 to 1948. -

Papers of Surrealism, Issue 8, Spring 2010 1

© Lizzie Thynne, 2010 Indirect Action: Politics and the Subversion of Identity in Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore’s Resistance to the Occupation of Jersey Lizzie Thynne Abstract This article explores how Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore translated the strategies of their artistic practice and pre-war involvement with the Surrealists and revolutionary politics into an ingenious counter-propaganda campaign against the German Occupation. Unlike some of their contemporaries such as Tristan Tzara and Louis Aragon who embraced Communist orthodoxy, the women refused to relinquish the radical relativism of their approach to gender, meaning and identity in resisting totalitarianism. Their campaign built on Cahun’s theorization of the concept of ‘indirect action’ in her 1934 essay, Place your Bets (Les paris sont ouvert), which defended surrealism in opposition to both the instrumentalization of art and myths of transcendence. An examination of Cahun’s post-war letters and the extant leaflets the women distributed in Jersey reveal how they appropriated and inverted Nazi discourse to promote defeatism through carnivalesque montage, black humour and the ludic voice of their adopted persona, the ‘Soldier without a Name.’ It is far from my intention to reproach those who left France at the time of the Occupation. But one must point out that Surrealism was entirely absent from the preoccupations of those who remained because it was no help whatsoever on an emotional or practical level in their struggles against the Nazis.1 Former dadaist and surrealist and close collaborator of André Breton, Tristan Tzara thus dismisses the idea that surrealism had any value in opposing Nazi domination. -

'Biographical Notes'

Originalveröffentlichung in: Spies, Werner (Hrsg.): Max Ernst : life and work, Köln 2005, S. 17-31 ‘BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES’ How Max Ernst Plays with a Literary Genre Julia Drost Self-assessments and Influences ‘Max Ernst is a liar, gold-digger, schemer, swindler, slanderer andboxer. ’ The words of a character assessment which Max Ernst drafted for an exhibition poster in T92T. They can be seen as the accompanying text alongside a photograph of the artist below a few important works and collages dating from his Dadaist period. Provocative and mocking self-assessments such as these are typical of Max Ernst, the ‘agent provocateur ’ and ‘most highly intellectual artist of the Surrealist movement ’, who mostly spoke of himself in the third person, and yet wrote more about his own oeuvre than almost any other artist.1 This constant reflection on his own work is characteristic of Max Ernst’s entire artistic career: he had already begun to comment on his curriculum vitae and his artistic creative process at an early date. His self- assessments in writing were continually revised and added to, and were finally published for the first time for the Cologne/Zurich exhibition cata logue in 1962 as Biographical Notes. Tissue of Truth - Tissue of Lies.1 This first detailed description of his entire life was preceded by various other writ ings, of which I shall briefly mention some here. In November 1921 the 17 JULIA DROST journal Das Junge Rheinland published a short article written by the artist himself, entitled simply Max Ernst ? In a special edition of Cahiers d ’Art devoted to the artist in Z936, Max Ernst reflected on his own creative process in the essay Au deld de la peinture (Beyond Painting).4 In 1942 the American magazine View brought out a special edition on Max Ernst, in which a first self-description by the artist was printed under the title Some data on the youth ofM. -

EXPRESSIONISM- NEO-PLASTICISM (De Stijl)- SURREALISM

04.12.2012 ART IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY: EXPRESSIONISM- NEO-PLASTICISM (De Stijl)- SURREALISM Week 9 Expressionism In Germany, a group known as Expressionists insisted art should express the artists feelings rather than images of the real world. The belief that the artist could directly convey some kind of inner feeling- - emotional or spiritual- - through art was a fashionable idea in German artistic and intellectual circles at the beginning of the twentieth century. Artists had been encouraged to ‘break free’ from civilized constraints and Academic conventions and somehow express themselves more freely; these ideas are fundamental to what we call German ‘Expressionist’ art. From 1905 to 1930, Expressionism the use of distorted, exaggerated forms and colors for emotional impact dominated German art. This subjective trend, which is the foundation of much twentieth century art, began with Van Gogh, Gauguin and Munch in the late nineteenth century, and continued with Belgian painter James Ensor (1860-1849), and Austrian painters Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), Egon Schiele (1890- 1918), and Oscar Kokoschka (1886-1980). But it was in Germany, with two separate groups Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, the Expressionism reached maturity. Die Brücke: Founded in 1905 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880- 1938) Der Blaue Reiter: Founded in Munich around 1911 by Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944). 1 04.12.2012 DIE BRÜCKE (BRIDGE): BRIDGING THE GAP • Die Brücke founded by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880- 1938) • Members include Ernst Ludwig in 1905. Kirchner (1880–1938), Erich • The aim was to sieze avantgarde spirit. Heckel (1883–1970), and Emil • Members believed their work would be a “bridge” to the Nolde (1867–1956). -

9. Silser Kunst- Und Literatourtage Donnerstag, 22

9. Silser Kunst- und LiteraTourtage Donnerstag, 22. bis Sonntag, 25. August 2013 9. Silser Kunst- und LiteraTourtage Bei den 9. Silser Kunst- und LiteraTourtagen stehen mit Erich Käst- ner, Joseph Roth und Max Ernst diesmal zwei Schriftsteller und ein bildender Künstler im Zentrum. Ziel der Silser Kunst- und LiteraTourtage ist, durch Lesungen und Vorträge, Kulturwanderungen, Filmvorführungen und Konzerte den Teilnehmenden jene Literaten, Musiker und bildenden Künstler nä- her zu bringen, die einen Bezug zum Engadin hatten oder haben. Der Schriftsteller Joseph Roth bildet hierzu eine Ausnahme: Der leiden- schaftliche Reisende und selbsternannte «Hotelbürger» war nämlich nie in dieser Region, vielleicht deshalb, weil er nicht gewusst hat, welch wunderbare Hotelpaläste ihn hier erwartet und inspiriert hätten! An- ders Erich Kästner, der bereits zu Beginn der 30er Jahre in St. Moritz weilte. Das dortige Grandhotel-Ambiente wurde zum Schauplatz sei- nes berühmten Romans «Drei Männer im Schnee» (1934). Nach dem II. Weltkrieg kehrte er ins Engadin zurück und liess sich dort zu weite- ren Texten u.a. über das Hotelmilieu inspirieren. Der deutsche Künstler Max Ernst lernte in den frühen 30er Jahren in Paris Alberto Giacometti kennen und verbrachte den Sommer 1934 bei seinem Freund in dessen Sommeratelier in Maloja, wo er auch seine ersten bildhauerischen Versuche unternahm. Mirella Carbone und Joachim Jung führen die Teilnehmer durch die Tage, die, wie immer, im einmaligen Ambiente des Hotel Waldhaus Sils stattfinden. Zwei hochkarätige Gastreferenten konnten gewonnen wer- den: Dr. Fritz Hackert, Mitherausgeber der sechsbändigen Ausgabe von Joseph Roths Werken, und Professor Werner Spies, der grosse Max-Ernst-Spezialist. Als Veranstalter zeichnen das Kulturbüro KUBUS, Sils-Tourismus und das Hotel Waldhaus Sils.