And Diversity of Its Bee Community in a Fragmented Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity of Rhizobia Associated with Amorpha Fruticosa Isolated from Chinese Soils and Description of Mesorhizobium Amorphae Sp

International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology (1999), 49, 5 1-65 Printed in Great Britain Diversity of rhizobia associated with Amorpha fruticosa isolated from Chinese soils and description of Mesorhizobium amorphae sp. nov. E. T. Wang,lt3 P. van Berkum,2 X. H. SU~,~D. Beyene,2 W. X. Chen3 and E. Martinez-Romerol Author for correspondence : E. T. Wang. Tel : + 52 73 131697. Fax: + 52 73 175581. e-mail: [email protected] 1 Centro de lnvestigacidn Fifty-five Chinese isolates from nodules of Amorpha fruticosa were sobre Fijaci6n de characterized and compared with the type strains of the species and genera of Nitrdgeno, UNAM, Apdo Postal 565-A, Cuernavaca, bacteria which form nitrogen-f ixing symbioses with leguminous host plants. A Morelos, Mexico polyphasic approach, which included RFLP of PCR-amplified 165 rRNA genes, * Alfalfa and Soybean multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE), DNA-DNA hybridization, 165 rRNA Research Laboratory, gene sequencing, electrophoretic plasmid profiles, cross-nodulation and a Ag ricuI tu ra I Research phenotypic study, was used in the comparative analysis. The isolates Service, US Department of Agriculture, BeltsviI le, M D originated from several different sites in China and they varied in their 20705, USA phenotypic and genetic characteristics. The majority of the isolates had 3 Department of moderate to slow growth rates, produced acid on YMA and harboured a 930 kb Microbiology, College of symbiotic plasmid (pSym). Five different RFLP patterns were identified among Biology, China Agricultural the 16s rRNA genes of all the isolates. Isolates grouped by PCR-RFLP of the 165 University, Beijing 100094, People’s Republic of China rRNA genes were also separated into groups by variation in MLEE profiles and by DNA-DNA hybridization. -

Outline of Angiosperm Phylogeny

Outline of angiosperm phylogeny: orders, families, and representative genera with emphasis on Oregon native plants Priscilla Spears December 2013 The following listing gives an introduction to the phylogenetic classification of the flowering plants that has emerged in recent decades, and which is based on nucleic acid sequences as well as morphological and developmental data. This listing emphasizes temperate families of the Northern Hemisphere and is meant as an overview with examples of Oregon native plants. It includes many exotic genera that are grown in Oregon as ornamentals plus other plants of interest worldwide. The genera that are Oregon natives are printed in a blue font. Genera that are exotics are shown in black, however genera in blue may also contain non-native species. Names separated by a slash are alternatives or else the nomenclature is in flux. When several genera have the same common name, the names are separated by commas. The order of the family names is from the linear listing of families in the APG III report. For further information, see the references on the last page. Basal Angiosperms (ANITA grade) Amborellales Amborellaceae, sole family, the earliest branch of flowering plants, a shrub native to New Caledonia – Amborella Nymphaeales Hydatellaceae – aquatics from Australasia, previously classified as a grass Cabombaceae (water shield – Brasenia, fanwort – Cabomba) Nymphaeaceae (water lilies – Nymphaea; pond lilies – Nuphar) Austrobaileyales Schisandraceae (wild sarsaparilla, star vine – Schisandra; Japanese -

Pollination of Cultivated Plants in the Tropics 111 Rrun.-Co Lcfcnow!Cdgmencle

ISSN 1010-1365 0 AGRICULTURAL Pollination of SERVICES cultivated plants BUL IN in the tropics 118 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO 6-lina AGRICULTUTZ4U. ionof SERNES cultivated plans in tetropics Edited by David W. Roubik Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Balboa, Panama Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations F'Ø Rome, 1995 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. M-11 ISBN 92-5-103659-4 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Publications Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. FAO 1995 PlELi. uion are ted PlauAr David W. Roubilli (edita Footli-anal ISgt-iieulture Organization of the Untled Nations Contributors Marco Accorti Makhdzir Mardan Istituto Sperimentale per la Zoologia Agraria Universiti Pertanian Malaysia Cascine del Ricci° Malaysian Bee Research Development Team 50125 Firenze, Italy 43400 Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia Stephen L. Buchmann John K. S. Mbaya United States Department of Agriculture National Beekeeping Station Carl Hayden Bee Research Center P. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Amorpha Canescens Pursh Leadplant

leadplant, Page 1 Amorpha canescens Pursh leadplant State Distribution Best Survey Period Photo by Susan R. Crispin Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Status: State special concern the Mississippi valley through Arkansas to Texas and in the western Great Plains from Montana south Global and state rank: G5/S3 through Wyoming and Colorado to New Mexico. It is considered rare in Arkansas and Wyoming and is known Other common names: lead-plant, downy indigobush only from historical records in Montana and Ontario (NatureServe 2006). Family: Fabaceae (pea family); also known as the Leguminosae. State distribution: Of Michigan’s more than 50 occurrences of this prairie species, the vast majority of Synonym: Amorpha brachycarpa E.J. Palmer sites are concentrated in southwest Lower Michigan, with Kalamazoo, St. Joseph, and Cass counties alone Taxonomy: The Fabaceae is divided into three well accounting for more than 40 of these records. Single known and distinct subfamilies, the Mimosoideae, outlying occurrences have been documented in the Caesalpinioideae, and Papilionoideae, which are last two decades from prairie remnants in Oakland and frequently recognized at the rank of family (the Livingston counties in southeast Michigan. Mimosaceae, Caesalpiniaceae, and Papilionaceae or Fabaceae, respectively). Of the three subfamilies, Recognition: Leadplant is an erect, simple to sparsely Amorpha is placed within the Papilionoideae (Voss branching shrub ranging up to ca. 1 m in height, 1985). Sparsely hairy plants of leadplant with greener characterized by its pale to grayish color derived from leaves have been segregated variously as A. canescens a close pubescence of whitish hairs that cover the plant var. -

Fruits and Seeds of Genera in the Subfamily Faboideae (Fabaceae)

Fruits and Seeds of United States Department of Genera in the Subfamily Agriculture Agricultural Faboideae (Fabaceae) Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1890 Volume I December 2003 United States Department of Agriculture Fruits and Seeds of Agricultural Research Genera in the Subfamily Service Technical Bulletin Faboideae (Fabaceae) Number 1890 Volume I Joseph H. Kirkbride, Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L. Weitzman Fruits of A, Centrolobium paraense E.L.R. Tulasne. B, Laburnum anagyroides F.K. Medikus. C, Adesmia boronoides J.D. Hooker. D, Hippocrepis comosa, C. Linnaeus. E, Campylotropis macrocarpa (A.A. von Bunge) A. Rehder. F, Mucuna urens (C. Linnaeus) F.K. Medikus. G, Phaseolus polystachios (C. Linnaeus) N.L. Britton, E.E. Stern, & F. Poggenburg. H, Medicago orbicularis (C. Linnaeus) B. Bartalini. I, Riedeliella graciliflora H.A.T. Harms. J, Medicago arabica (C. Linnaeus) W. Hudson. Kirkbride is a research botanist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Systematic Botany and Mycology Laboratory, BARC West Room 304, Building 011A, Beltsville, MD, 20705-2350 (email = [email protected]). Gunn is a botanist (retired) from Brevard, NC (email = [email protected]). Weitzman is a botanist with the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Botany, Washington, DC. Abstract Kirkbride, Joseph H., Jr., Charles R. Gunn, and Anna L radicle junction, Crotalarieae, cuticle, Cytiseae, Weitzman. 2003. Fruits and seeds of genera in the subfamily Dalbergieae, Daleeae, dehiscence, DELTA, Desmodieae, Faboideae (Fabaceae). U. S. Department of Agriculture, Dipteryxeae, distribution, embryo, embryonic axis, en- Technical Bulletin No. 1890, 1,212 pp. docarp, endosperm, epicarp, epicotyl, Euchresteae, Fabeae, fracture line, follicle, funiculus, Galegeae, Genisteae, Technical identification of fruits and seeds of the economi- gynophore, halo, Hedysareae, hilar groove, hilar groove cally important legume plant family (Fabaceae or lips, hilum, Hypocalypteae, hypocotyl, indehiscent, Leguminosae) is often required of U.S. -

The Very Handy Bee Manual

The Very Handy Manual: How to Catch and Identify Bees and Manage a Collection A Collective and Ongoing Effort by Those Who Love to Study Bees in North America Last Revised: October, 2010 This manual is a compilation of the wisdom and experience of many individuals, some of whom are directly acknowledged here and others not. We thank all of you. The bulk of the text was compiled by Sam Droege at the USGS Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab over several years from 2004-2008. We regularly update the manual with new information, so, if you have a new technique, some additional ideas for sections, corrections or additions, we would like to hear from you. Please email those to Sam Droege ([email protected]). You can also email Sam if you are interested in joining the group’s discussion group on bee monitoring and identification. Many thanks to Dave and Janice Green, Tracy Zarrillo, and Liz Sellers for their many hours of editing this manual. "They've got this steamroller going, and they won't stop until there's nobody fishing. What are they going to do then, save some bees?" - Mike Russo (Massachusetts fisherman who has fished cod for 18 years, on environmentalists)-Provided by Matthew Shepherd Contents Where to Find Bees ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Nets ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Netting Technique ...................................................................................................................................... -

Assessing the Potential Distribution of Invasive Alien Species Amorpha

A peer-reviewed open-access journal Nature ConservationAssessing 30: 41–67the potential (2018) distribution of invasive alien species Amorpha fruticosa... 41 doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.30.27627 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://natureconservation.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity conservation Assessing the potential distribution of invasive alien species Amorpha fruticosa (Mill.) in the Mureş Floodplain Natural Park (Romania) using GIS and logistic regression Gheorghe Kucsicsa1, Ines Grigorescu1, Monica Dumitraşcu1, Mihai Doroftei2, Mihaela Năstase3, Gabriel Herlo4 1 Institute of Geography, Romanian Academy, 12 D. Racoviţă Street, sect. 2, 023993, Bucharest, Romania 2 Danube Delta National Institute, 165 Babadag Street, 820112, Tulcea, Romania 3 National Forest Ad- ministration, Protected Areas Department, 9A Petricani Street, sect. 2, Bucharest, Romania 4 National Forest Administration, Mureş Floodplain Natural Park Administration, Pădurea Ceala FN, Arad, Romania Corresponding author: Monica Dumitraşcu ([email protected]) Academic editor: Maurizio Pinna | Received 19 June 2018 | Accepted 2 October 2018 | Published 24 October 2018 http://zoobank.org/EF484149-F35A-4B0F-9F8B-4F8164BFF94F Citation: Kucsicsa G, Grigorescu I, Dumitraşcu M, Doroftei M, Năstase M, Herlo G (2018) Assessing the potential distribution of invasive alien species Amorpha fruticosa (Mill.) in the Mureş Floodplain Natural Park (Romania) using GIS and logistic regression. Nature Conservation 30: 41–67. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.30.27627 -

Hymenoptera: Apoidea) Habitat in Agroecosystems Morgan Mackert Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2019 Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems Morgan Mackert Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Mackert, Morgan, "Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 17255. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/17255 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Strategies to improve native bee (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) habitat in agroecosystems by Morgan Marie Mackert A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Program of Study Committee: Mary A. Harris, Co-major Professor John D. Nason, Co-major Professor Robert W. Klaver The student author, whose presentation of the scholarship herein was approved by the program of study committee, is solely responsible for the content of this thesis. The Graduate College will ensure this thesis is globally accessible and will not permit alterations after a degree is conferred. Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2019 Copyright © Morgan Marie Mackert, 2019. All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iv ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER 1. -

Acanthoscelides Pallidipennis

118373_Vol_2.qxp 8/16/04 10:10 AM Page 867 Entomology BIOLOGY OF A NEW BRUCHID SPECIES IN HUNGARY: ACANTHOSCELIDES PALLIDIPENNIS Zoltán Horváth, Kecskemét High School, High School Faculty of Horticulture, Kecskemét, Hungary Gábor Bujáki, Szent István University, GödöllĘ, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In July 1984, tiny bruchid adults were observed feeding until maturation on the composite flowers of sunflower, in the edges of a hybrid sunflower seed production field surrounded by forest strips. The species, emerging in high numbers, was identified as Acanthoscelides pallidipennis Motschulsky Fall (syn. Acanthoscelides collusus Fall), originating from North America. The species is monophagous. Its host plant is Amorpha fruticosa L. (desert false indigo), also originating from North America. Larvae develop in the seeds. Adults of the overwintering generation emerge early in the spring (end of March, beginning of April). Emergence may take a long time. Adults feed for maturation on the flowers of early weeds, e.g., Reseda lutea L. (weld), Artemisia spp., and Orobanche major L. (great broomrape). Following the feeding period, from the end of May until the end of August, adults lay their eggs continuously on the young pods of A. fruticosa. Adults of the new generation emerge in June, feed on the characteristically bursting anthers of A. fruticosa, but they also visit the male parent plants of the sunflower hybrid seed production fields. In these fields, pollination capacity of the damaged male parent plants is significantly reduced, especially at the field edges. Thus, within the pest fauna of sunflower, A. pallidipensis can be categorized as a typical pest on the edges of fields. -

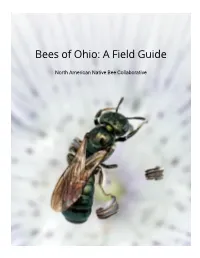

Bees of Ohio: a Field Guide

Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide North American Native Bee Collaborative The Bees of Ohio: A Field Guide (Version 1.1.1 , 5/2020) was developed based on Bees of Maryland: A Field Guide, authored by the North American Native Bee Collaborative Editing and layout for The Bees of Ohio : Amy Schnebelin, with input from MaLisa Spring and Denise Ellsworth. Cover photo by Amy Schnebelin Copyright Public Domain. 2017 by North American Native Bee Collaborative Public Domain. This book is designed to be modified, extracted from, or reproduced in its entirety by any group for any reason. Multiple copies of the same book with slight variations are completely expected and acceptable. Feel free to distribute or sell as you wish. We especially encourage people to create field guides for their region. There is no need to get in touch with the Collaborative, however, we would appreciate hearing of any corrections and suggestions that will help make the identification of bees more accessible and accurate to all people. We also suggest you add our names to the acknowledgments and add yourself and your collaborators. The only thing that will make us mad is if you block the free transfer of this information. The corresponding member of the Collaborative is Sam Droege ([email protected]). First Maryland Edition: 2017 First Ohio Edition: 2020 ISBN None North American Native Bee Collaborative Washington D.C. Where to Download or Order the Maryland version: PDF and original MS Word files can be downloaded from: http://bio2.elmira.edu/fieldbio/handybeemanual.html. -

High Line Plant List Stay Connected @Highlinenyc

BROUGHT TO YOU BY HIGH LINE PLANT LIST STAY CONNECTED @HIGHLINENYC Trees & Shrubs Acer triflorum three-flowered maple Indigofera amblyantha pink-flowered indigo Aesculus parviflora bottlebrush buckeye Indigofera heterantha Himalayan indigo Amelanchier arborea common serviceberry Juniperus virginiana ‘Corcorcor’ Emerald Sentinel® eastern red cedar Amelanchier laevis Allegheny serviceberry Emerald Sentinel ™ Amorpha canescens leadplant Lespedeza thunbergii ‘Gibraltar’ Gibraltar bushclover Amorpha fruticosa desert false indigo Magnolia macrophylla bigleaf magnolia Aronia melanocarpa ‘Viking’ Viking black chokeberry Magnolia tripetala umbrella tree Betula nigra river birch Magnolia virginiana var. australis Green Shadow sweetbay magnolia Betula populifolia grey birch ‘Green Shadow’ Betula populifolia ‘Whitespire’ Whitespire grey birch Mahonia x media ‘Winter Sun’ Winter Sun mahonia Callicarpa dichotoma beautyberry Malus domestica ‘Golden Russet’ Golden Russet apple Calycanthus floridus sweetshrub Malus floribunda crabapple Calycanthus floridus ‘Michael Lindsey’ Michael Lindsey sweetshrub Nyssa sylvatica black gum Carpinus betulus ‘Fastigiata’ upright European hornbeam Nyssa sylvatica ‘Wildfire’ Wildfire black gum Carpinus caroliniana American hornbeam Philadelphus ‘Natchez’ Natchez sweet mock orange Cercis canadensis eastern redbud Populus tremuloides quaking aspen Cercis canadensis ‘Ace of Hearts’ Ace of Hearts redbud Prunus virginiana chokecherry Cercis canadensis ‘Appalachian Red’ Appalachian Red redbud Ptelea trifoliata hoptree Cercis