Levels of Style in Narrative Fiction: an Aspect of the Interpersonal Metafunction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01 to 06 MAY Terry Waite

Mark Billingham Ross Collins Kerry Brown Maura Dooley Matt Haig Darren Henley Emma Healey Patrick Gale Guernsey Literary Erin Kelly Huw Lewis-Jones Adam Kay Kiran Millwood Hargrave Kiran FestivalLibby Purves 2019 Lionel Shriver Philip Norman Philip 01 TO 06 MAY Terry Waite Terry Chrissie Wellington Piers Torday Lucy Siegle Lemn Sissay MBE Jessica Hepworth Benjamin Zephaniah ANA LEAF FOUNDATION MOONPIG APPLEBY OSA RECRUITMENT BROWNS ADVOCATES PRAXISIFM BUTTERFIELD RANDALLS DOREY FINANCIAL MODELLING RAWLINSON & HUNTER GUERNSEY ARTS COMMISSION ROTHSCHILD & CO GUERNSEY POST SPECSAVERS JULIUS BAER THE FORT GROUP Sophy Henn Kindly sponsored by sponsored Kindly THE INTERNATIONAL STOCK EXCHANGE THE GUERNSEY SOCIETY Turning the Tide on Plastic: How St James: £10/£5 Lucy Siegle Humanity (And You) Can Make Our Welcome to the Globe Clean Again seventh Guernsey Presenter on BBC’s The One Show and columnist for the Observer and the Guardian, Lucy Siegle offers a unique and beguiling perspective on environmental issues and ethical consumerism. Turning the Tide on Literary Festival Plastic provides a powerful call to arms to end the plastic pandemic along with the tools we need to make decisive change. It is a clear- eyed, authoritative and accessible guide to help us to take decisive and 13:00 to 14:00 effective personal action. Thursday 2 May Message from Sponsored by PraxisIFM Message from Claire Allen, Terry Waite CBE OGH Hotel: £25 Festival Director This is Going to Hurt Business Breakfast As Honorary I am very proud to welcome Professor Kerry you to the seventh Guernsey Chairman of the Literary Festival! With over Adam Kay Thursday 2 May Brown: The World Guernsey Literary 19:30 to 20:30 60 events for all interests According to Xi Festival it is once and ages, the festival is a Kerry Brown is Professor of again my pleasure unique opportunity to be inspired by writers. -

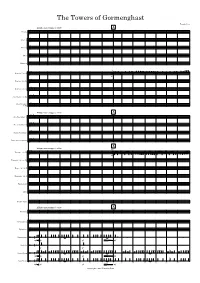

The-Towers-Of-Gormenghast-Web.Pdf

The Towers of Gormenghast Timothy Rees Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Piccolo ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 1 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Flute 2 & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Oboe & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bassoon ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Tpt. j j j j j œ œ Clarinet 1 in Bb ° # 6 Œ™ Œ j œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ j œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ & # 8 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ œ œ œ œ ∑ mf ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 2 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Clarinet 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Clarinet in Eb # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Bass Clarinet # in Bb # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Alto Saxophone 1 ° # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Alto Saxophone 2 # # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tenor Saxophone # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Baritone Saxophone # # # 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢& 8 A Allegro non troppo q . = 108 solo Trumpet 1 in Bb ° # j j œ œ œ j œ œ œ œ & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ™ Œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ œ ™ œ œ œ mfœ œ J J J œ J J Trumpet 2 & 3 in Bb # & # 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Horn 1 & 2 in F # & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Trombone 1 & 2 ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Euphonium ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Tuba ? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Double Bass ? 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Allegro non troppo q . = 108 A Timpani °? 6 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ¢ 8 Glockenspiel ° & 86 ‰ ‰ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ -

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected]

BECKY SHRIMPTON 416.300.8237 – [email protected] - www.beckyshrimpton.com Agent – Paul Smith - ETM HEIGHT: 5’5’’ WEIGHT: 140 lbs HAIR: Dark Brown EYES: Green SELECTED FILM & TELEVISION Stress Vaccine Lead Tom Mae/Tom Mae Productions Be Alert Bert – Martial Arts Lead Lisa Lovatt/ITV Be Alert Bert – Shoplifting Lead James Martins/ITV The Ghost is a Lie Lead Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Surviving Evil – Season 2 Episode 4 Principal Emily/Schooley/Laughing Cat Productions Giving You the Business Season 1 Episode 8 Principal Joel Goldberg/FoodNetwork USA Canada! Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Irresistible Force Principal Cameron Maitland/Farmervision Mask-a-raid Principal Liza Callahan/VFS Productions Cutaway Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films The Missing Me Principal Attila Kallai/Atka Films The Drinking Helps Principal Josh Kingston/Mom's Proud Productions Tower Principal Kazik Radwanski/MDFF Films Inspiration Actor Jason Armstrong/Skeleton Key Global Films Strange Famous Music Video Actor Dustin Kuypers/The Documentarians Motives and Murders Season 5 Episode 6 Actor Cineflix Productions SELECTED ANIMATION VOICE OVER Fireman Sam Helen Flood Susan Hart/Kitchen Sync Mage and Minions Female Heroes John Welch/Making Fun Inc. Doki Multiple Characters Susan Hart/Investigation Kids Brambleberry Tales Narrator David Lam/Rival Schools Firefall Nina Ian Macmillan/VFS Productions HellBent Beatrix Samantha Satiago/Ringling Animations DecorView Kate Chad Parker/FunnelBox Media Ring Run Circus Nina Sebastian Fernandez/Kalio Productions -

Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone Ebook Free Download

THE GORMENGHAST NOVELS: TITUS GROAN / GORMENGHAST / TITUS ALONE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mervyn Laurence Peake | 1168 pages | 01 Dec 1995 | Overlook Press | 9780879516284 | English | New York, United States The Gormenghast Novels: Titus Groan / Gormenghast / Titus Alone PDF Book Tolkien, but his surreal fiction was influenced by his early love for Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson rather than Tolkien's studies of mythology and philology. It was very difficult to get through or enjoy this book, because it feels so very scattered. But his eyes were disappointing. Nannie Slagg: An ancient dwarf who serves as the nurse for infant Titus and Fuchsia before him. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. I honestly can't decide if I liked it better than the first two or not. So again, mixed feelings. There is no swarmer like the nimble flame; and all is over. How does this vast castle pay for itself? The emphasis on bizarre characters, or their odd characteristics, is Dickensian. As David Louis Edelman notes, the prescient Steerpike never seems to be able to accomplish much either, except to drive Titus' father mad by burning his library. At the beginning of the novel, two agents of change are introduced into the stagnant society of Gormenghast. However, it is difficult for me to imagine how such readers could at once praise Peake for the the singular, spectacular world of the first two books, and then become upset when he continues to expand his vision. Without Gormenghast's walls to hold them together, they tumble apart in their separate directions, and the narrative is a jumbled climb around a pile of disparate ruins. -

Society Pages

COMING TO THE MORRIN CENTRE IN NOVEMBER CÉILIDH ECHOES OF SCOTLAND N U M B E R 2 9 ■ F a l l 2 0 1 0 ■ $ 2 . 0 0 Inspired by the fascinating history of the leaving Scotland, the memory of the logdriver’s Scottish pioneers, in 2009, Le Cochon waltz, nostalgia for milling frolics… The SouRiant in collaboration with the Oscar Dhu multimedia effects and projection of old Cultural Centre and Fig55 created Céilidh photos; family portraits and animations help Echoes of Scotland. This performance binds the audience to imagine early life in “Canada, together theatre, multimedia images, new the land of everlasting forest and cold”. It is a technologies, storytelling, singing, journey that weaves together the past and instrumental music, dancing and poetry. present, Gaelic, English and French languages, nostalgia, happiness, humour and The play is steeped in the history of the first tradition. ■ Scottish Pioneer settlers, who exiled from the Isle of Lewis, settled in the Eastern Townships This theatre piece was based on historical and LOUISE PENNY of Quebec. The audience is invited to a céilidh ethnological documents, from the works of BOOK (kaylee), a visit or gathering at the taigh- Margaret Bennett, the Oscar Dhu Cultural ceilidh, or “ceilidh house”. The ceilidh is Center archives and documents and LAUNCH structured around stories, poems, proverbs, information provided by Lingwick residents, ■ anecdotes, jokes, dances, songs and music particularly the descendants of the Scottish taken from the life stories of the first settlers. Céilidh Echoes of Scotland is a CÉILIDH Hebridean settlers. The occasion is the collective creation by Tess LeBlanc, André ECHOES OF reunion between a brother, Seamus, and Bombardier, Michel Fordin and Martine sister, Sine. -

Booklet Gormenghast

A FANTASY OPERA BY IRMIN SCHMI DT Irmin Schmidt, founder of the legendary group CAN, has written an opera: GORMENGHAST. Commissioned by Wuppertaler Bühnen, the work was performed in the English language and premiered at the Operahouse Wuppertal on 15. November 1998. Inspired by Mervyn Peake’s masterpiece of gothic fantasy, English novelist Duncan Fallowell wrote the libretto in St. Petersburg, combining romance, comedy and futurism into an adventure of epic strangeness peopled by unforgettable characters. The opera is in 3 acts and centres on the rise and fall of Steerpike, a courageous, clever and charming kitchen-boy who becomes by degrees the murderous tyrant of Gormenghast Castle and its domain. In the process he bewitches and destroys Fuchsia the daughter of Gormen ghast’s opium-addicted ruler. Finally he meets his own dramatic death. The other inhabitants of this vivid decaying realm are drawn into the terrible tale. Irmin Schmidt, who studied under Ligeti and Stockhausen, not only created in CAN one of the most influential of avant garde groups, but is also a classical conductor and pianist and has com- posed music for over 70 film productions. His work transforms elements of the popular, ethnic and classical into a wholly original musical language . In both libretto and music, this integration of high culture and popular culture is not like any- thing which has gone before: it is achieved with perfect naturalness, carrying the art of opera forward into a new phase. The result is both accessible and magically unexpected: GORMENGHAST is a major addition to the world of musical theatre. -

Music-Week-2000-02-0

FOR EVERVONE IN THE^ BUSINESS OF MUSIC ''S'1'/ UN • -gX music week Ames and Berry vow to keep label culture by Ajax Scott labels. The process is still not men.setRoger Ames to runand Warner Ken Berry, EMI theMusic, two rumoursestablished. suggesting There willthis alwaysis how webe overbave cost-cuttingpledged to inplace the oompanycreativity plan to do it. Well ail the rumours theydeal experthas receivedto fashion regulatoryonce the The two were speaking days Gabrielle yesterdayFerdy (Sunday) Unger-Hamilton to be the first was label challenging boss since with Puff his Daddyartist Mondayafter the of public the $20bn announcement merger of lastthe to have co-produced a track to reach number one. By the end of two companies to create an opéra- Thursdayher slender Gabrielle lead at (above),the start at of more the week than to35,000 more sales,than 6,000 had extended unlts over tionglobal that music will bemarket. number With one annual in the their management structure shortly elosest challengers REM and Britney Spears for the number one slot. Her sales of around $8bn and earnings Deal makers: Ames (left) and Berry TopRise 10 album placing, - which easily had beating fallen outits previousof the Top number 100 - 25 was peak. on course Unger- for a . ofannual $lbn, savings they ofexpert around to $250mrealise judgementsstarting out asfrom to howand onewell weof thedo Hamilton with Ollie Dagois originally sampled Bob Dylan's Knockin' On within three years, involuing a will be too see how good we are at itHeaven's to Gabrielle Door to 18 record months with ago producer and put Johnny together Dollar. -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #94 June — August, 2011 Hours: M-F 10 am to 8 pm RECENTLY RECEIVED AND FORTHCOMING SCIENCE FICTION Sat. 10 am to 6 pm; Sun. Noon to 5 pm ALREADY RECEIVED Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Doctor Who Insider #1 (US version of the long-running Doctor Who Magazine. Fax 612-827-6394 Matt Smith on his latest foe, the Silence; the Sontarans; more). $6.99 E-mail: [email protected] Doctor Who Magazine #431 (Controversial Dalek redesign; writer Mark Gatiss Website: www.UncleHugo.com reveals some clues about his new episode; Janet Fielding uncovered; more).. $8.99 Doctor Who Magazine #432 (New series secrets; Matt Smith Karen Gillan, and Award News Arthur Darvill star in a special mini-adventure for Comic Relief; David Tennant tells us what he's doing for Red Nose Day; more). $8.99 Doctor Who Magazine #433 (Exclusive interview with Steven Moffat; Marked The nominees for Hugo Awards for Death? Amy Pond, The Doctor, River Song, Rory Pond: one of them will die in the for Best Novel are Cryoburn by Lois season opener; more. Four separate collectors' covers, one featuring each character)$.8.99 McMaster Bujold ($25.00 signed), Feed Fantasy & Science Fiction May/June 2011 (New fiction, reviews, more).$7.50 by Mira Grant ($9.99), The Hundred Locus #603 April 2011 (Interviews with Shaun Tan and Dani & Eytan Kollin; Thousand Kingdoms by N. K. Jemisin industry news, reviews, more)......................................... -

Booklet-Smaller.Pdf

INDEX 3 - 4 Biography Irmin Schmidt (English) 5 - 7 Introduction by Irmin Schmidt (English) 8 Synopsis (English) 9 -10 Characters (English) 11 Casting and production requirements (English) 12 - 14 Info to previous productions in Wuppertal, Gelsenkirchen, Saarbrücken and Luxembourg 15 - 16 Projektbeschreibung von Irmin Schmidt (Deutsch) 17 Synopsis (Deutsch) 18 - 19 Charaktere (Deutsch) 20 Info zu Bestetzung und Aufführungsmaterial (Deutsch) 21 - 28 Photos 29 - 36 Press IRMIN SCHMIDT BIOGRAPHY Irmin Schmidt, born in May 1937, received a formal musical education. Between 1957 and 1967 he studied conducting (u.o. with Istvan Kertesz), compositon (u.o. with Stockhausen and Ligeti) and piano (u.o. with Detlef Kraus). Between 1962 and 1969 he conducted numerous orchestras including Wiener Sinfoniker, Bochumer Sinfoniker, Radio-Sinfonie-Orchester Norddeutscher Rundfunk Hannover and the Dortmunder Ensemble für Neue Musik, which he founded. Schmidt also worked as a musical director at the Stadttheater Aachen and taught Musicals and Chanson at the Bochum stage school. Schmidt also gave numerous piano recitals focusing on new music and was amongst the first German pianists to interpret the work of John Cage. His composition "Hexapussy" was premiered in Frankfurt in 1967 and shown on television by WDR. "Ilgom" was premiered by Radio Stuttgart in 1968. During this period he also composed music for various film and theatre productions. His classical career was put on hold after a trip to New York in 1966 which exposed him to emerging musical forms and ideas that led to him forming CAN in 1968. As the band's keyboard player, Schmidt’s contribution to their groundbreaking career and the evolution of electronic music in general is formidable. -

Titus Groan · Gormenghast · Titus Alone Himself, Had a Son, Moved to Sussex, Publication), in the House Previously and Begun the Writing of Titus Groan

Other works on Naxos AudioBooks The Master and Margarita Frankenstein (Bulgakov) ISBN: 9789626349359 (Shelley) ISBN: 9789626340035 Read by Julian Rhind-Tutt Read by Daniel Philpott Bleak House Our Mutual Friend (Dickens) ISBN: 9789626344316 (Dickens) ISBN: 9789626344422 Read by Sean Barrett and Teresa Gallagher Read by David Timson www.naxosaudiobooks.com CD 1 For a complete catalogue and details of how to order other 1 Gormenghast taken by itself would have displayed... 7:23 Naxos AudioBooks titles please contact: 2 5:33 As Flay passed the curator on his way to the door... 3 It was impossible for the apprentices to force themselves... 5:43 In the UK: Naxos AudioBooks, Select Music & Video Distribution, 4 He peered at the immobile huddle of limbs. 4:40 3 Wells Place, Redhill, Surrey RH1 3SL. 5 From his vantage point he was able to get a clear view... 7:47 Tel: 01737 645600. 6 Her Ladyship, the seventy-sixth Countess of Groan... 4:06 In the USA: Naxos of America Inc., 7 Every morning of the year... 4:43 1810 Columbia Ave., Suite 28, Franklin, TN37064. 8 5:30 Mrs Slagg entered. Tel: +1 615 771 9393 9 Leaving the tray on the mat outside... 3:13 Mrs Slagg made her way along the narrow stone path... 6:40 In Australia: Select Audio/Visual Distribution Pty. Ltd., B Titus, under the care of Nannie Slagg and Keda... 6:58 PO Box 691, Brookvale, NSW 2100. Tradition playing its remorseless part... 6:35 Tel: +61 299481811 Meanwhile, hiding behind a turn in the passage... 4:49 order online at Mr Flay was possessed by two major vexations. -

Collected Articles on Mervyn Peake

Collected Articles on Mervyn Peake G. Peter Winnington Introduction This collEcTion reprints some of my articles on Peake spanning the last 40 years; they are available as pdf files, with appropriate illustrations. Total length 200 pages. not all were published in the Mervyn Peake Review or Peake Studies. some have appeared before only in books or other periodicals. i have grouped them more or less thematically, rather than chronologically. i © G. Peter Winnington 2016 consider the first two as introductory: they were written for people with The words and art work by Mervyn Peake little or no knowledge of Peake and his work. The first, ‘inside the Mind are copyright the Mervyn Peake Estate. of Mervyn Peake’, examines how Peake spatializes the contents of the mind; the second, ‘The critical Reception of the Titus Books,’shows how Peake’s novels were first received. The second group is largely biographical in orientation, covering • ‘Peake’s Parents’ Years in china’; • my discovery of ‘A letter From china’ by Peake; • a piece describing ‘Kuling, Peake’s Birthplace’ and a more recent one, • ‘Peake and Kuling’, written as a review of the British library’s publica- tion of ‘Memoirs of a Doctor in china’, misleadingly titled Peake in China with an ill-informed introduction by hilary spurling; • ‘Burning the Globe: another attempt to situate Gormenghast’, on the geography and mentality of Gormenghast; and • ‘The Writing of Titus Groan.’ The third group comprises articles identifying some of Peake’s sources and possible influences on his work: • ‘Tracking Down the Umzimvubu Kaffirs’; • ‘Peake, Knole and Orlando’; • ‘Mervyn Peake and the cinema’ (updated with a note on recent find- ings); • ‘Parodies and Poetical Allusions’; • ‘Peake and Alice (and Arrietty)’. -

By Mervyn Peake Stage Adaptation by John Constable September 18 to 27, 2008 Frederic Wood Theatre

Presents: by Mervyn Peake Stage Adaptation by John Constable September 18 to 27, 2008 Frederic Wood Theatre The UBC Department of Theatre and Film presents an intimate conversation with: Richard Ouzounian (playwright, producer, director, and currently theatre critic for The Toronto Star) as TH E NA K ED CR ITIC Wednesday, September 24, 12-1 pm Dorothy Somerset Studio Theatre 6361 University Boulevard Everyone is welcome. Bring your lunch! A Servant of Two Masters by Carlo Goldoni Translated & Adapted by Jeffrey Hatcher& Paolo Emilio Landi extra event series October 14 to 18, 2008 7:30 pm Dorothy Somerset Studio Theatre Directed by Stephen Heatley November 13 to 22, 2008 Frederic Wood Theatre by Kevin Kerr Directed by UNITY Stephen Drover (1918) Presents: by Mervyn Peake Stage Adaptation by John Constable Directed by Stephen Malloy Scenography by Ronald Fedoruk Costume Design by Carmen Alatorre Songs by Patrick Pennefather Original Music by Cristina Mihaela Istrate Sound Design by Jason Ho September 18 to 27, 2008 Frederic Wood Theatre Welcome to Theatre at UBC, 2008-09 The opening of a new theatre season is always an exciting event, and in my 36(!) years at UBC I’ve never been more excited than I am about this one. We’ve got world classics (Medea and A Servant of Two Masters), modern Canadian classics (Unity (1918) and Billy Bishop Goes to War), an English Gothic fantasy (Gormenghast), and an American comedy about a Russian novel (The Idiots Karamazov). Two of these shows are directed by UBC Theatre faculty, two by Theatre alumni—Billy Bishop and Unity, both Governor General’s Award winners written by two of our other alumni—and two by current graduate students in the Theatre Program.