Respiratory: Bronchodilators for COPD

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Product Insert (PDF)

PRODUCT INFORMATION Piclamilast Item No. 29170 CAS Registry No.: 144035-83-6 Formal Name: 3-(cyclopentyloxy)-N-(3,5-dichloro- 4-pyridinyl)-4-methoxy-benzamide O Synonyms: RP 73401, RPR 73401 Cl H MF: C18H18Cl2N2O3 FW: 381.3 N O Purity: ≥98% O Supplied as: A solid N Storage: -20°C Cl Stability: ≥2 years Information represents the product specifications. Batch specific analytical results are provided on each certificate of analysis. Laboratory Procedures Piclamilast is supplied as a solid. A stock solution may be made by dissolving the piclamilast in the solvent of choice, which should be purged with an inert gas. Piclamilast is soluble in organic solvents such as ethanol and DMSO. The solubility of piclamilast in ethanol is approximately 20 mM and approximately 100 mM in DMSO. Description 1 Piclamilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor (IC50 = 0.31 nM). It is selective for PDE4 over PDE1, 2,3 PDE2, PDE3, PDE5, and PDE7A in cell-free assays (IC50s = >100, 40, >100, 14, and >10 μM, respectively). Piclamilast inhibits superoxide production by guinea pig eosinophils and histamine-induced contraction 1,4 in isolated guinea pig trachea (IC50s = 24 and 2 nM, respectively). It inhibits eosinophil, neutrophil, lymphocyte, and TNF-α accumulation in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from ovalbumin-sensitized 5 rats (ED50s = 23.8, 14.1, 19.5, and 14.4 μmol/kg, respectively). Piclamilast also inhibits ovalbumin-induced 2 bronchoconstriction in a guinea pig model of asthma (ED50 = 0.033 mg/kg). References 1. Ashton, M.J., Cook, D.C., Fenton, G., et al. Selective type IV phosphodiesterase inhibitors as antiasthmatic agents. -

Doxofylline, a Novofylline Inhibits Lung Inflammation Induced By

Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 27 (2014) 170e178 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ypupt Doxofylline, a novofylline inhibits lung inflammation induced by lipopolysacharide in the mouse Yanira Riffo-Vasquez*, Francis Man, Clive P. Page Sackler Institute of Pulmonary Pharmacology, Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, King’s College London, UK article info abstract Article history: Rational: Doxofylline is a xanthine drug that has been used as a treatment for respiratory diseases for Received 20 December 2013 more than 30 years. In addition to doxofylline being a bronchodilator, some studies have indicated that Received in revised form doxofylline also has anti-inflammatory properties, although little is known about the effect of this drug 30 December 2013 on lung inflammation. Accepted 2 January 2014 Objectives: We have investigated the actions of doxofylline against the effects of Escherichia coli LPS in the lungs of BALB/c mice. Keywords: Methods: Animals have been treated with doxofylline (0.1, 0.3 and 1 mg/kg i.p.) 24, -and 1 h before, and Doxofylline m Neutrophils 6 h after intra-nasal instillation of LPS (10 g/mouse). Readouts were performed 24 h later. fi LPS Results: Doxofylline at 1 and 0.3, but not at 0.1 mg/kg, signi cantly inhibit neutrophil recruitment to the Lung lung induced by LPS (LPS: 208.4 Æ 14.5 versus doxofylline: 1 mg/kg: 106.2 Æ 4.8; 0.3 mg/kg: 4 Inflammation 105.3 Æ 10.7 Â 10 cells/ml). Doxofylline significantly inhibited IL-6 and TNF-a release into BAL fluid in Mice comparison to LPS-treated animals (LPS: 1255.6 Æ 143.9 versus doxofylline 1 mg/kg: 527.7 Æ 182.9; 0.3 mg/kg: 823.2 Æ 102.3 pg/ml). -

PDE4-Inhibitors: a Novel, Targeted Therapy for Obstructive Airways Disease Zuzana Diamant, Domenico Spina

PDE4-inhibitors: A novel, targeted therapy for obstructive airways disease Zuzana Diamant, Domenico Spina To cite this version: Zuzana Diamant, Domenico Spina. PDE4-inhibitors: A novel, targeted therapy for obstructive airways disease. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2011, 24 (4), pp.353. 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.12.011. hal-00753954 HAL Id: hal-00753954 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00753954 Submitted on 20 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Title: PDE4-inhibitors: A novel, targeted therapy for obstructive airways disease Authors: Zuzana Diamant, Domenico Spina PII: S1094-5539(11)00006-X DOI: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.12.011 Reference: YPUPT 1071 To appear in: Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics Received Date: 2 October 2010 Revised Date: 5 December 2010 Accepted Date: 24 December 2010 Please cite this article as: Diamant Z, Spina D. PDE4-inhibitors: A novel, targeted therapy for obstructive airways disease, Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics (2011), doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.12.011 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

FDA Briefing Document Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting

FDA Briefing Document Pulmonary-Allergy Drugs Advisory Committee Meeting August 31, 2020 sNDA 209482: fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol fixed dose combination to reduce all-cause mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease NDA209482/S-0008 PADAC Clinical and Statistical Briefing Document Fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol fixed dose combination for all-cause mortality DISCLAIMER STATEMENT The attached package contains background information prepared by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the panel members of the advisory committee. The FDA background package often contains assessments and/or conclusions and recommendations written by individual FDA reviewers. Such conclusions and recommendations do not necessarily represent the final position of the individual reviewers, nor do they necessarily represent the final position of the Review Division or Office. We have brought the supplemental New Drug Application (sNDA) 209482, for fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium/vilanterol, as an inhaled fixed dose combination, for the reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with COPD, to this Advisory Committee in order to gain the Committee’s insights and opinions, and the background package may not include all issues relevant to the final regulatory recommendation and instead is intended to focus on issues identified by the Agency for discussion by the advisory committee. The FDA will not issue a final determination on the issues at hand until input from the advisory committee process has been considered -

Pharmaceutical Appendix to the Tariff Schedule 2

Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE HARMONIZED TARIFF SCHEDULE Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2007) (Rev. 2) Annotated for Statistical Reporting Purposes PHARMACEUTICAL APPENDIX TO THE TARIFF SCHEDULE 2 Table 1. This table enumerates products described by International Non-proprietary Names (INN) which shall be entered free of duty under general note 13 to the tariff schedule. The Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) registry numbers also set forth in this table are included to assist in the identification of the products concerned. For purposes of the tariff schedule, any references to a product enumerated in this table includes such product by whatever name known. ABACAVIR 136470-78-5 ACIDUM LIDADRONICUM 63132-38-7 ABAFUNGIN 129639-79-8 ACIDUM SALCAPROZICUM 183990-46-7 ABAMECTIN 65195-55-3 ACIDUM SALCLOBUZICUM 387825-03-8 ABANOQUIL 90402-40-7 ACIFRAN 72420-38-3 ABAPERIDONUM 183849-43-6 ACIPIMOX 51037-30-0 ABARELIX 183552-38-7 ACITAZANOLAST 114607-46-4 ABATACEPTUM 332348-12-6 ACITEMATE 101197-99-3 ABCIXIMAB 143653-53-6 ACITRETIN 55079-83-9 ABECARNIL 111841-85-1 ACIVICIN 42228-92-2 ABETIMUSUM 167362-48-3 ACLANTATE 39633-62-0 ABIRATERONE 154229-19-3 ACLARUBICIN 57576-44-0 ABITESARTAN 137882-98-5 ACLATONIUM NAPADISILATE 55077-30-0 ABLUKAST 96566-25-5 ACODAZOLE 79152-85-5 ABRINEURINUM 178535-93-8 ACOLBIFENUM 182167-02-8 ABUNIDAZOLE 91017-58-2 ACONIAZIDE 13410-86-1 ACADESINE 2627-69-2 ACOTIAMIDUM 185106-16-5 ACAMPROSATE 77337-76-9 -

Environmental Risk Assessment Data Roflumilast

Environmental Risk Assessment Data Roflumilast Roflumilast is an anti-inflammatory medicine called phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor. Roflumilast reduces the activity of phosphodiesterase-4, a protein occurring naturally in body cells. When the activity of this protein is reduced, there is less inflammation in the lungs. This helps to stop narrowing of airways occurring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), thus easing breathing problems. Roflumilast is an active pharmaceutical ingredient used in the following AstraZeneca product: Daxas. In a human pharmacokinetics study with radiolabelled roflumilast, total recovery of radioactivity amounted to 90 % of the dose, 70 % being excreted in urine and about 20 % in faeces. Roflumilast itself is not detectable in urine, and its active metabolite roflumilast N-oxide is detected only in small amounts (1%). Instead, 4 inactive metabolites, each about 10 – 15 % were found in urine. The origin of radioactivity in faeces was not investigated. Roflumilast is not readily biodegradable, nor is it expected to bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms. The Predicted Environmental Concentration (PEC) / Predicted No Effect Concentration (PNEC) ratio is 1.6 x 10-2, which means use of roflumilast is predicted to present a low risk to the environment. Predicted Environmental Concentration (PEC) The PEC is based on the following data: PEC (µg/L) = (A*109*(100-R))/(365*P*V*D*100) A (kg/year) = total patient consumption of roflumilast in the European country with the highest per capita use in 2016 (Source: IMS Health1) R (%) = % removal during wastewater (sewage) treatment (due to loss by adsorption to sludge particles, by volatilisation, hydrolysis or biodegradation). It is assumed that R = 0 as a worst case. -

Potential Treatment Benefits and Safety of Roflumilast in COPD: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Journal name: International Journal of COPD Article Designation: Review Year: 2016 Volume: 11 International Journal of COPD Dovepress Running head verso: Yuan et al Running head recto: Roflumilast in COPD open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S106370 Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Potential treatment benefits and safety of roflumilast in COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis Lianfang Yuan1 Background: Current evidence suggests that roflumilast is efficacious in treating COPD, Xuan Dai1 especially in preventing the acute exacerbation of COPD. Meng Yang2 Objectives: This study was designed to evaluate the clinical effects and safety of roflumilast Qiling Cai1 in the treatment of stable COPD using randomized clinical trial (RCT) data. Na Shao1 Methods: A MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register search was carried out. RCTs reporting the treatment effects of roflumilast in COPD were identified. Relevant data 1Department of Respiration, Tianjin were extracted and a meta-analysis was performed. Hospital of ITCWM (Tianjin Nankai Hospital), 2Department of Pharmacy, Results: A total of nine articles and 13 RCT studies were identified. Overall, 29.1% of the Tianjin Medical University Cancer subjects in the roflumilast group showed evidence of exacerbation. The corresponding figure Institute and Hospital, Key Laboratory For personal use only. of Cancer Prevention and Therapy, was 32.2% in the placebo group. According to pooled analysis, the use of roflumilast reduced Tianjin, People’s Republic of China COPD exacerbations in comparison to placebo (odds ratio [OR] =0.82, 95% confidence inter- val [CI] =0.75–0.9). The quality of life and spirometry were improved. -

Recommendation 084 Trelegy and Trimbow in Chronic Obstructive

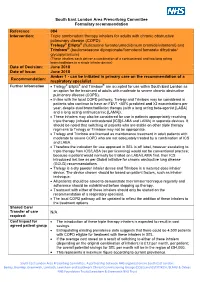

South East London Area Prescribing Committee Formulary recommendation Reference 084 Intervention: Triple combination therapy inhalers for adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Trelegy® Ellipta® (fluticasone furoate/umeclidinium bromide/vilanterol) and Trimbow® (beclometasone dipropionate/formoterol fumarate dihydrate/ glycopyrronium) (These inhalers each deliver a combination of a corticosteroid and two long acting bronchodilators in a single inhaler device) Date of Decision: June 2018 Date of Issue: June 2018 Amber 1 - can be initiated in primary care on the recommendation of a Recommendation: respiratory specialist Further Information • Trelegy® Ellipta® and Trimbow® are accepted for use within South East London as an option for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). • In line with the local COPD pathway, Trelegy and Trimbow may be considered in patients who continue to have an FEV1 <50% predicted and ≥2 exacerbations per year, despite dual bronchodilation therapy (with a long acting beta-agonist [LABA] and a long acting antimuscarinic [LAMA]). • These inhalers may also be considered for use in patients appropriately receiving triple therapy (inhaled corticosteroid [ICS]/LABA and LAMA) in separate devices. It should be noted that switching of patients who are stable on other triple therapy regimens to Trelegy or Trimbow may not be appropriate. • Trelegy and Trimbow are licensed as maintenance treatment in adult patients with moderate to severe COPD who are not adequately treated by a combination of ICS and LABA. • Therefore the indication for use approved in SEL is off label, however escalating to triple therapy from ICS/LABA (as per licensing) would not be conventional practice; because a patient would normally be trialled on LABA/LAMA first, then ICS introduced last line as per Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease (GOLD) recommendations. -

Benralizumab for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) NIHRIO (HSRIC) ID: 6086 NICE ID: 9196

NIHR Innovation Observatory Evidence Briefing: November 2017 Benralizumab for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) NIHRIO (HSRIC) ID: 6086 NICE ID: 9196 LAY SUMMARY Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (sometimes called chronic bronchitis or emphysema) is a lung disease that causes difficulties in breathing, mostly due to narrowing of the airways. The main cause of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is smoking. Symptoms of this disease include increased difficulty breathing when active, persistent cough, and frequent chest infections. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease can have a sudden worsening of symptoms, known as an ‘exacerbation’ or ‘flare‐up’, which can lead to being admitted to hospital. Benralizumab is a new drug being developed for the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It is administered by injection under the skin and acts by targeting specific proteins that causes the airway to narrow. If benralizumab is licensed for use in the UK, it could be a new treatment option for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that may improve quality of life and reduce the number of exacerbations. This briefing is based on information available at the time of research and a limited literature search. It is not intended to be a definitive statement on the safety, efficacy or effectiveness of the health technology covered and should not be used for commercial purposes or commissioning without additional information. This briefing presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed1 are those of the author and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. TARGET GROUP Moderate to very severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); patients with exacerbation history. -

Doxofylline Is Not Just Another Theophylline!

Journal name: International Journal of COPD Article Designation: Review Year: 2017 Volume: 12 International Journal of COPD Dovepress Running head verso: Matera et al Running head recto: Doxofylline tolerability profile and risk-to-benefit ratio open access to scientific and medical research DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S150887 Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW Doxofylline is not just another theophylline! Maria Gabriella Matera1 Abstract: Doxofylline, which differs from theophylline in containing the dioxalane group at Clive Page2 position 7, has comparable efficacy to theophylline in the treatment of respiratory diseases, but Mario Cazzola3 with an improved tolerability profile and a favorable risk-to-benefit ratio. Furthermore, it does not have significant drug–drug interactions as exhibited with theophylline, which make using theo- 1Department of Experimental Medicine, Unit of Pharmacology, phylline more challenging, especially in elderly patients with co-morbidities receiving multiple University of Campania ‘Luigi classes of drug. It is now clear that doxofylline also possesses a distinct pharmacological profile 2 Vanvitelli’, Naples, Italy; Sackler from theophylline (no significant effect on any of the known phosphodiesterase isoforms, no Institute of Pulmonary Pharmacology, Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, significant adenosine receptor antagonism, no direct effect on histone deacetylases, interaction King’s College London, London, with β -adrenoceptors) and therefore, should not be considered as just a modified theophylline. UK; 3Department of Experimental 2 Medicine and Surgery, Chair of Randomized clinical trials of doxofylline to investigate the use of this drug to reduce exacerba- Respiratory Medicine, University of tions and hospitalizations due to asthma or COPD as an alternative to expensive biologics, and Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, Rome, Italy certainly as an alternative to theophylline are to be encouraged. -

Roflumilast (Daliresp®) Reference Number: ERX.NSMN.20 Effective Date: 12/15 Revision Log Last Review Date: 09/16

Clinical Policy: roflumilast (Daliresp®) Reference Number: ERX.NSMN.20 Effective Date: 12/15 Revision Log Last Review Date: 09/16 Clinical policies are intended to be reflective of current scientific research and clinical thinking. This policy is current at the time of approval, may be updated and therefore is subject to change. This Clinical Policy is not intended to dictate to providers how to practice medicine, nor does it constitute a contract or guarantee regarding payment or results. Providers are expected to exercise professional medical judgment in providing the most appropriate care, and are solely responsible for the medical advice and treatment of members. This policy is the property of Envolve Pharmacy Solutions. Unauthorized copying, use, and distribution of this Policy or any information contained herein is strictly prohibited. By accessing this policy, you agree to be bound by the foregoing terms and conditions, in addition to the Site Use Agreement for Health Plans associated with Envolve Pharmacy Solutions. Description The intent of the criteria is to ensure that patients follow selection elements established by Envolve Pharmacy Solutions for the use of roflumilast (Daliresp®). Policy/Criteria It is the policy of health plans affiliated with Envolve Pharmacy Solutions® that roflumilast (Daliresp®) is medically necessary for members meeting the following criteria: Initial Approval Criteria (must meet all): A. Diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); B. Age ≥ 18 years; C. FEV1 < 50% within the last 30 days; D. Failure of ≥ 12 weeks of adherent use of one of the following: a. PDL combination inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting beta2 adrenergic agonist (LABA) agent; b. -

Atypical Respiratory Medications -May 2019

Indian Health Service National Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee Formulary Brief: Atypical Respiratory Medications -May 2019- Background: In May 2019, the IHS National Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee (NPTC) reviewed atypical respiratory medications which included biologic therapies for uncontrolled/severe asthma and phosphodiesterase inhibitors for COPD. Currently, none of these medications are available on the National Core Formulary. Following clinical and pharmacoeconomic analyses, no modifications were made to the National Core Formulary. Discussion: Asthma is a lung disease associated with chronic inflammation and airway narrowing due to an imbalance and shift towards generating more T-helper 2 (Th2) cytokines.1 For those who do not achieve symptom control with high dose inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), biologics can be considered. These biologics target specific interleukins produced by the Th2 cytokines to disrupt the signaling cascade which includes: omalizumab (binds to IgE), reslizumab and mepolizumab (bind to IL-5), benralizumab (blocks IL-5 receptor), dupilumab (blocks IL-4 receptor).2 Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a progressive lung disease due to long term damage from irritants, primarily tobacco smoke.3 Phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors can be utilized as alternative agents for severe, uncontrolled COPD. Theophylline is a non-selective PDE inhibitor; however, the utility of this agent is limited by its narrow therapeutic window and increased risk of significant adverse events. Roflumilast selectively inhibits phosphodiesterase-4 which is expressed in airway smooth muscle. Overall, PDE inhibition results in airway smooth muscle relaxation.4 =Guidelines= Biologics are reserved as adjunctive therapy for patients with uncontrolled difficult-to-treat/severe asthma despite optimized standard therapy.