Kjburnett Land Between Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges

LAURA T. RAYNOLDS Professor, Department of Sociology, Director, Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Colorado State University Email: [email protected] Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges ABSTRACT Fairtrade International certification is the primary social certification in the agro-food sector in- tended to promote the well-being and empowerment of farmers and workers in the Global South. Although Fairtrade’s farmer program is well studied, far less is known about its labor certification. Helping fill this gap, this article provides a systematic account of Fairtrade’s labor certification system and standards and com- pares it to four other voluntary programs addressing labor conditions in global agro-export sectors. The study explains how Fairtrade International institutionalizes its equity and empowerment goals in its labor certifica- tion system and its recently revised labor standards. Drawing on critiques of compliance-based labor stand- ards programs and proposals regarding the central features of a ‘beyond compliance’ approach, the inquiry focuses on Fairtrade’s efforts to promote inclusive governance, participatory oversight, and enabling rights. I argue that Fairtrade is making important, but incomplete, advances in each domain, pursuing a ‘worker- enabling compliance’ model based on new audit report sharing, living wage, and unionization requirements and its established Premium Program. While Fairtrade pursues more robust ‘beyond compliance’ advances than competing programs, the study finds that, like other voluntary initiatives, Fairtrade faces critical challenges in implementing its standards and realizing its empowerment goals. KEYWORDS fair trade, Fairtrade International, multi-stakeholder initiatives, certification, voluntary standards, labor rights INTRODUCTION Voluntary certification systems seeking to improve social and environmental conditions in global production have recently proliferated. -

1 Doherty, B, Davies, IA (2012), Where Now for Fair Trade, Business History

Doherty, B, Davies, I.A. (2012), Where now for fair trade, Business History, (Forthcoming) Abstract This paper critically examines the discourse surrounding fair trade mainstreaming, and discusses the potential avenues for the future of the social movement. The authors have a unique insight into the fair trade market having a combined experience of over 30 years in practice and 15 as fair trade scholars. The paper highlights a number of benefits of mainstreaming, not least the continued growth of the global fair trade market (tipped to top $7 billion in 2012). However the paper also highlights the negative consequences of mainstreaming on the long term viability of fair trade as a credible ethical standard. Keywords: Fair trade, Mainstreaming, Fairtrade Organisations, supermarket retailers, Multinational Corporations, Co-optation, Dilution, Fair-washing. Introduction Fair trade is a social movement based on an ideology of encouraging community development in some of the most deprived areas of the world1. It coined phrases such as “working themselves out of poverty” and “trade not aid” as the mantras on which growth and public acceptance were built.2 As it matured it formalised definitions of fair trade and set up independent governance and monitoring organisations to oversee fair trade supply-chain agreements and the licensing of participants. The growth of fair trade has gone hand-in-hand with a growth in mainstream corporate involvement, with many in the movement perceiving engagement with the market mechanism as the most effective way of delivering societal change.3 However, despite some 1 limited discussion of the potential impacts of this commercial engagement4 there has been no systematic investigation of the form, structures and impacts of commercial engagement in fair trade, and what this means for the future of the social movement. -

Fair Trade 1 Fair Trade

Fair trade 1 Fair trade For other uses, see Fair trade (disambiguation). Part of the Politics series on Progressivism Ideas • Idea of Progress • Scientific progress • Social progress • Economic development • Technological change • Linear history History • Enlightenment • Industrial revolution • Modernity • Politics portal • v • t [1] • e Fair trade is an organized social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries to make better trading conditions and promote sustainability. It advocates the payment of a higher price to exporters as well as higher social and environmental standards. It focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine,[2] fresh fruit, chocolate, flowers, and gold.[3] Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect that seek greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[4] There are several recognized Fairtrade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO/Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing -

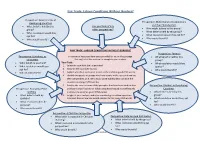

Fair Trade: Labour Conditions Without Borders?

Fair Trade: Labour Conditions Without Borders? Perspective: Governments of Perspective: Multi-National Corporations Developing Countries and their Shareholders • What belief is held by this Can you think of any • Who might belong to this group? group? other perspectives? • What belief is held by this group? • What resolution would they opt for? • What resolution would they opt for? • Who would benefit? • Who would benefit? FAIR TRADE: LABOUR CONDITIONS WITHOUT BORDERS? Perspective: Farmers Perspective: Ourselves, as A number of resources have been provided for you in this package. • What belief is held by this consumers Use any/ all of the material to complete your analysis. group? Your Task: • What belief do you hold? • What resolution would they 1. Select an issue from the list provided. • What resolution would you opt for? 2. Describe the issue (150 words) opt for? • Who would benefit? 3. Explain why this is an issue of justice or the common good (150 words). • Who would benefit? 4. Identify the people or groups who have a stake in the issue and analyse their perspectives on it. Why would some stakeholders not want the situation to change? (750 words) 5. Analyse the issue in terms of the principles that have been studied that Perspective: Workers in Developing Perspective: Economist Peter promote human flourishing. Which perspective would most effectively Countries Griffiths promote the common good? (750 words) • What belief is held by this • What belief is held by 6. In light of your analysis, and after considering the ethical questions group? Griffiths? provided, discuss how you would respond to this issue. -

Faq I Fair Trade Winnipeg

__ I FAQ I FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG WHO IS FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG? COMMITTEE FairTrade Winnipeg is a collaborative, community-based working group that includes fair MEMBERS trade advocates from government, the private sector and civil society. The Fair Trade Winnipeg steering committee was formed in 2014 to achieve the common Donna Dagg goal of making Winnipeg a Fair Trade Town. In 2017, Fair Trade Winnipeg accomplished that Manitoba Liquor goal and the City of Winnipeg was officially designated as Canada’s 25th Fair Trade Town. In & Lotteries order to maintain this designation for years to come, the committee will continue to advance fair trade in partnership with the City of Winnipeg; building support through community Zack Gross awareness, involvement, and product availability. Fair Trade Manitoba Naomi Johnson WHAT IS A FAIR TRADE TOWN? Canadian A Fair Trade Town is a community where people and organizations use their everyday choices Foodgrains Bank and buying power to increase sales of Fairtrade Certified products and bring about positive Larissa Kanhai change for farmers and workers in developing countries. The Fair Trade Town program in University of Canada is part of a global movement that recognizes more than 1,850 communities in 32 Manitoba countries, that have taken steps to advance fair trade. There are 24 other Fair Trade Towns in Canada, including major cities like Vancouver, Edmonton and Toronto; and in Manitoba, Gimli, Lindsay Mierau Brandon and Selkirk. Winnipeg is now Canada’s 25th Fair Trade Town and Manitoba’s 4th. City of Winnipeg Program qualifications are managed by the Canadian FairTrade Network (www.cftn.ca) and Kyra Moshtaghi Nia Fairtrade Canada (www.fairtrade.ca) Canadian Fair Trade Network WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A FAIR TRADE TOWN? Megan Redmond In order to be officially designated as a Fair Trade Town, a city must: Manitoba Council for International 1. -

Fair Trade Books & Films Films

Fair Trade Books & Films This list of Fair Trade books and films will help you educate yourself and your campus or community about Fair Trade principles and advocacy efforts Films • The True Cost (2015) • Summary: The True Cost is a documentary that sheds light on the unseen human and environmental impacts of the clothing industry. http://truecostmovie.com/ • Director: Andrew Morgan • Run time: 92 minutes • Available: on iTunes, VHX, Netflix, Amazon Instant Video, Blue Ray, DVD • Dukale’s Dream (2015) • Summary: Hugh Jackman and his wife travel to Ethiopia, where they meet a young coffee farmer named Dukale, who inspires them to support the fair trade movement. http://dukalesdream.com/ • Director: Josh Rothstein • Run time: 70 minutes • Available: on iTunes, Google Play, Amazon, Xfinity, Local screenings • The Dark Side of Chocolate (2010) • Summary: An investigative documentary exposing exploitative child labor in the chocolate industry. • Director: Miki Mistrati, U. Roberto Romano • Run Time: 46 minutes • Available: Free on YouTube: https://youtu.be/7Vfbv6hNeng • Food Chains (2014) • Summary: In this exposé, an intrepid group of Florida farmworkers battle to defeat the $4 trillion global supermarket industry through their ingenious Fair Food program, which partners with growers and retailers to improve working conditions for farm laborers in the United States. http://www.foodchainsfilm.com/ • Director: Sanjay Rawal • Run Time: 1 hour 26 minutes • Available: iTunes, Netflix, Amazon instant video, screening in theaters and on campuses. Fair Trade Books & Films This list of Fair Trade books and films will help you educate yourself and your campus or community about Fair Trade principles and advocacy efforts Films • Beyond Fair Trade: Doi Chaang Coffee (2011) • Summary: Global TV’s half hour special on Doi Chaang Coffee and the unique relationship with their farmers from the Akha Hill Tribe of Northern Thailand. -

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: a Case Study of the Green Campus Co-Operative

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of the Green Campus Co-operative By: Madison Hopper Supervised By: Rod MacRae A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 31 July 2018 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................. 4 FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION: WHO’S TO BLAME?.......................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................................... 12 SOCIAL ENTERPRISES ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Hybrid Business Models ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Mission Quality - TOMS shoes .......................................................................................................................... -

Fair Trade: Social Regulation in Global Food Markets

Journal of Rural Studies 28 (2012) 276e287 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Rural Studies journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jrurstud Fair Trade: Social regulation in global food markets Laura T. Raynolds* Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Sociology Department, Clark Building, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523, United States abstract Keywords: This article analyzes the theoretical and empirical parameters of social regulation in contemporary global Regulation food markets, focusing on the rapidly expanding Fair Trade initiative. Fair Trade seeks to transform Globalization North/South relations by fostering ethical consumption, producer empowerment, and certified Fair Trade commodity sales. This initiative joins an array of labor and environmental standard and certification Certification systems which are often conceptualized as “private regulations” since they depend on the voluntary participation of firms. I argue that these new institutional arrangements are better understood as “social regulations” since they operate beyond the traditional bounds of private and public (corporate and state) domains and are animated by individual and collective actors. In the case of Fair Trade, I illuminate how relational and civic values are embedded in economic practices and institutions and how new quality assessments are promoted as much by social movement groups and loosely aligned consumers and producers as they are by market forces. This initiative’s recent commercial success has deepened price competition and buyer control and eroded its traditional peasant base, yet it has simultaneously created new openings for progressive politics. The study reveals the complex and contested nature of social regulation in the global food market as movement efforts move beyond critique to institution building. -

American University a Sip in the Right Direction: The

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY A SIP IN THE RIGHT DIRECTION: THE DEVELOPMENT OF FAIR TRADE COFFEE AN HONORS CAPSTONE SUBMITTED TO THE AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM GENERAL UNIVERSITY HONORS BY ALLISON DOOLITTLE WASHINGTON, D.C. APRIL 2009 Copyright © 2009 by Allison Doolittle All rights reserved ii Coffee is more than just a drink. It is about politics, survival, the Earth and the lives of indigenous peoples. Rigoberta Menchu iii CONTENTS ABSTRACT . vi Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Goals of the Research Background on Fair Trade Coffee 2. LITERATURE REVIEW . 4 The Sociology of Social Movements and Resource Mobilization Fair Trade as a Social Movement Traditional Studies and the Failure to Combine Commodity Chain Analysis with Social Movement Analysis to Study Fair Trade 3. NONGOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF FAIR TRADE . 9 Alternative Trade for Development Alternative Trade for Solidarity Horizontal and Vertical Institution-building within the Movement Roles of Nongovernmental Organizations in Fair Trade Today 4. STRATEGIC COMMUNICATIONS TO TRANSFORM PUBLICS INTO SYMPATHIZERS . 20 Initial Use of Labels and Narratives to Tell the Fair Trade Story The Silent Salesman: Coffee Packaging that Compels Consumers Fair Trade Advertising, Events and Public Relations Fair Trade and Web 2.0: Dialogue in the Social Media Sphere Internet Use by Coffee Cooperatives to Reach Consumers iv 5. DRINKING COFFEE WITH THE ENEMY: CORPORATE INVOLVEMENT IN FAIR TRADE COFFEE . 33 Market-Driven Corporations: Friend or Foe? Fair Trade as a Corporate Strategy for Appeasing Activists and Building Credibility Fair Trade as a Strategy to Reach Conscious Consumers Internal Debates on Mainstreaming Fair Trade Coffee 6. CONCLUSIONS . -

Éthique Publique, Vol. 21, N° 1 | 2019 Le Mouvement Des Villes Équitables Entre Militantisme Et Certification Éthiqu

Éthique publique Revue internationale d’éthique sociétale et gouvernementale vol. 21, n° 1 | 2019 Certification de l'éthique et enjeux éthiques de la certification Le mouvement des villes équitables entre militantisme et certification éthique des lieux Jérôme Ballet et Aurélie Carimentrand Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ethiquepublique/4449 DOI : 10.4000/ethiquepublique.4449 ISSN : 1929-7017 Éditeur Éditions Nota bene Ce document vous est offert par Université Bordeaux Montaigne Référence électronique Jérôme Ballet et Aurélie Carimentrand, « Le mouvement des villes équitables entre militantisme et certification éthique des lieux », Éthique publique [En ligne], vol. 21, n° 1 | 2019, mis en ligne le 24 septembre 2019, consulté le 30 septembre 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ ethiquepublique/4449 ; DOI : 10.4000/ethiquepublique.4449 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 30 septembre 2019. Tous droits réservés Le mouvement des villes équitables entre militantisme et certification éthiqu... 1 Le mouvement des villes équitables entre militantisme et certification éthique des lieux Jérôme Ballet et Aurélie Carimentrand Introduction 1 Cet article s’intéresse aux processus de certification du commerce équitable à travers l’analyse du mouvement des villes équitables. Il s’agit dans ce cas de certifier un lieu (par l’intermédiaire d’une communauté ou d’une collectivité locale) plutôt qu’un produit ou une organisation. Le mouvement des villes équitables se décline dans un processus plus ou moins participatif à configuration d’acteurs variable selon les contextes. À partir d’une comparaison de cas issus de la littérature (Angleterre, France, États-Unis, Inde principalement), nous interrogeons la gouvernance de cette certification qui repose sur un double niveau. -

Can Scotland Still Call Itself a Fair Trade Nation?

Can Scotland still call itself a Fair Trade Nation? A report by the Scottish Fair Trade Forum JANUARY 2017 CAN SCOTLAND STILL CALL ITSELF A FAIR TRADE NATION? Scottish Fair Trade Forum Robertson House 152 Bath Street Glasgow G2 4TB +44 (0)141 3535611 www.sftf.org.uk www.facebook.com/FairTradeNation www.twitter.com/FairTradeNation [email protected] Scottish charity number SC039883 Scottish registered company number SC337384. Acknowledgements The Scottish Fair Trade Forum is very grateful for the help and advice received during the preparation of this report. We would like to thank everyone who has surveys and those who directly responded been involved, especially the Assessment to our personalised questionnaires: Andrew Panel members, Patrick Boase (social auditor Ashcroft (Koolskools Founding Partner), registered with the Social Audit Network UK Amisha Bhattarai (representative of Get Paper who chaired the Assessment Panel), Dr Mark Industry – GPI, Nepal), Mandira Bhattarai Hayes (Honorary Fellow in the Department of (representative of Get Paper Industry – GPI, Theology and Religion at Durham University, Nepal), Rudi Dalvai (President of the World Chair of the WFTO Appeals Panel and Fair Trade Organisation – WFTO), Patricia principal founder of Shared Interest), Penny Ferguson (Former Convener of the Cross Newman OBE (former CEO of Cafédirect and Party Group on Fair Trade in the Scottish currently a Trustee of Cafédirect Producers’ Parliament), Elen Jones (National Coordinator Foundation and Drinkaware), Sir Geoff Palmer at Fair Trade Wales), -

Project Assignment Fairtrade Standard for Coffee Review (Revised September 2020) Rationale for and Justification of Need For

FAIRTRADE INTERNATIONAL – STANDARDS & PRICING Project Assignment Fairtrade Standard for Coffee Review (revised September 2020) This project assignment contains the most important information about the project. For additional information on the project, please contact the project manager (contact details below). The project will be carried out according to the Standard Operating Procedures for the Development of Fairtrade Standards/Minimum Prices and Premiums. More information on these procedures can be found on the website: http://www.fairtrade.net/standards/setting-the-standards.html Rationale for and justification of need for the project: The Coffee Standard review is the opportunity to adapt and to ensure that the Standard is in line with the strategy 2016-2020 and contributes to its achievement. The strategy places great emphasis on the impact for producers, which is also key in the global coffee strategy 2016-2020. One of the key objectives of the global strategy is to ensure that "standards allow equity and impact." Additionally, it is vital to have a Coffee Standard that supports the empowerment and development of producer organizations. Therefore, the revision of the Standard will focus on these aspects. In addition to this, the global coffee context has evolved, on one hand producers face increased weather volatility and diseases leading to reduction in production, an ever increasing COSP and sustained low market prices. On the other hand, there is a greater consolidation of buying power among roasters, retailers, importers and exporters which has eroded the trading power of Fairtrade small-scale producers. The roaster’s and retailer's seek long term supply commitments, nevertheless buying forward creates significant price risk in volatile commodity markets.