José Mourinho “Please Don't Call Me Arrogant, but I'm European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Former Celtic and Southampton Manager Gordon Strachan Discusses Rangers' Recent Troubles, Andre Villas-Boas and Returning to Management

EXCLUSIVE: Former Celtic and Southampton manager Gordon Strachan discusses Rangers' recent troubles, Andre Villas-Boas and returning to management. RELATED LINKS • Deal close on pivotal day for Rangers • Advocaat defends spending at Rangers • Bet on Football - Get £25 Free You kept playing until you were 40 and there currently seems to be a trend for older players excelling, such as Giggs, Scholes, Henry and Friedel. What do you put this down to? Mine was due to necessity rather than pleasure, to be honest with you. I came to retire at about 37, but I went to Coventry and I was persuaded by Ron Atkinson, then by players at the club, and then by the chairman at the club, that I should keep playing so that was my situation. The secret of keeping playing for a long time is playing with good players. There have been examples of people playing on - real top, top players - who have gone to a lower level and found it really hard, and then calling it a day. The secret is to have good players around you, you still have to love the game and you have to look after yourself. You will find that the people who have played for a long time have looked after themselves really at an early age - 15 to 21 -so they have got a real base fitness in them. They trained hard at that period of time, and hard work is not hard work to them: it becomes the norm. How much have improvements in lifestyle, nutrition and other techniques like yoga and pilates helped extend players' careers? People talked about my diet when I played: I had porridge, bananas, seaweed tablets. -

Jose Mourinho: the Art of Winning: What the Appointment of the Special One Tells Us About Manchester United and the Premier League by Andrew J

Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League by Andrew J. Kirby ebook Ebook Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning: What the appointment of the Special One tells us about Manchester United and the Premier League please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback:::: 276 pages+++Publisher:::: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (August 19, 2016)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1537012363+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1537012360+++Product Dimensions::::5.1 x 0.6 x 7.8 inches++++++ ISBN10 1537012363 ISBN13 978-1537012 Download here >> Description: The manager everyone loves to hate… Mercurial Portuguese manager Jose Mourinho, who regards himself as football’s equivalent of George Clooney, featured in his own blockbuster this summer when he took charge of Manchester United – the world’s biggest club. The news sent shockwaves through the Old Trafford faithful – generations of whom have pledged their loyalty to a succession of managerial legends including Sir Matt Busby and Sir Alex Ferguson. At the very outset of what promises to be a tumultuous season for the Red Devils, Andrew J Kirby investigates in his latest book Jose Mourinho: The Art of Winning whether the latest controversial move by the club’s owners is a marriage made in heaven or hell. Machiavellian schemer, marketing man’s dream, inspirational leader and motivator, arrogant “manager-lout”, Super Coach. -

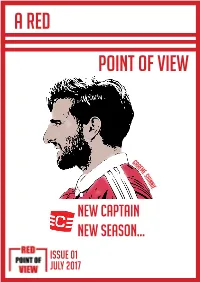

A Red Point of View – Issue 1

A RED Point of View GRAEME SHINNIE NEW CAPTAIN NEW SEASON... ISSUE 01 JULY 2017 Welcome... cONTRIBUTORS: It is with great pleasure that I welcome Ryan Crombie: you to “A Red Point of View” the unof- @ryan_crombie ficial online Dons magazine. We are an entirely new publication, dedicated to Ally Begg: bringing you content based upon the @ally_begg club we love. As a regular blogger and writer, I have written many pieces on the Scott Baxter: club I have supported from birth, this perhaps less through choice but family @scottscb tradition. I thank my dad for this. As a re- Matthew Findlay: sult of engaging and sharing my personal @matt_findlay19 writing across social media for several years now, I have grown to discover the monumental online Dons support that Tom Mackinnon: exists across all platforms. The aim of @tom_mackinnon this magazine is to provide a focal point for Aberdeen fans online, to access some Martin Stone: of the best writing that the support have @stonefish100 to offer, whilst giving the writers a plat- form to voice anything and everything Finlay Hall: Dons related. In this first issue we have @FinHall a plethora of content ranging from the pre-season thoughts from one of the Red Army’s finest, Ally Begg, to an ex- Mark Gordon: @Mark_SGordon clusive interview with Darren Mackie, who opens up about his lengthy time at Pittodrie. Guest writer Scott Baxter, Lewis Michie: the club photographer at Aberdeen tells @lewismichie0 what it’s like to photograph the Dons. Finlay Hall analyses the necessity of Ewan Beattie: fanzines and we get some views from @Ewan_Beattie the terraces as fans send in their pieces. -

Professional Coach: the Link Between Science and Media

Sport Science Review, vol.Sport XXV, Science No. Review, 1-2, May vol. XXV,2016 no. 1-2, 2016, 73 - 84 DOI: 10.1515/ssr-2016-0004 Professional Coach: The Link between Science and Media Boris ,BLUMENSTEIN1 • Iris, ORBACH2 port science and sport media give special attention to professional Scoaches from individual and team sport. However, there is not a lot of knowledge on those two approaches: Science and media. Therefore, the purpose of this article was to present sport science approach oriented on research, and sport media approach based on description of “coach life stories”. In this article we describe five cases of individual and team coaches. Similarities and difference in these two approaches are discussed. Key words: Science, Media, Professional Coach 1 Ribstein Center for Sport Medicine Sciences and Research, Wingate Institute for Physical Education and Sport, Israel 2 Givat Washington Academic College, Israel ISSN: (print) 2066-8732/(online) 2069-7244 73 © 2016 • National Institute for Sport Research • Bucharest, Romania Coach: Science And Media Professional Coach: The Link between Science and Media Modern competitive sport, including Olympic Games, is considered as a professional area, being affected by science approaches and popular media coverage. When analyzing athlete’s achievement it can be seen that the coach takes an essential role in helping athletes to improve and achieve success. We can learn about the coaches’ approach from the sport media and the sport science. The sport media gives athletes and coaches’ achievement and their life stories a place in the sport coverage. Moreover, in sport science many articles can be found focusing on athletes and coaches characteristics. -

Book of Condolences

Book of Condolences Ewan Constable RIP JIM xx Thanks for the best childhood memories and pu;ng Dundee United on the footballing map. Ronnie Paterson Thanks for the memories of my youth. Thoughts are with your family. R I P Thank you for all the memoires, you gave me so much happiness when I was growing up. You were someone I looked up to and admired Those days going along to Tanadice were fantasEc, the best were European nights Aaron Bernard under the floodlights and seeing such great European teams come here usually we seen them off. Then winning the league and cups, I know appreciate what an achievement it was and it was all down to you So thank you, you made a young laddie so happy may you be at peace now and free from that horrible condiEon Started following United around 8 years old (1979) so I grew up through Uniteds glory years never even realised Neil smith where the success came from I just thought it was the norm but it wasn’t unEl I got a bit older that i realised that you were the reason behind it all Thank you RIP MR DUNDEE UNITED � � � � � � � � Michael I was an honour to meet u Jim ur a legend and will always will be rest easy jim xxx� � � � � � � � First of all. My condolences to Mr. McLean's family. I was fortunate enough to see Dundee United win all major trophies And it was all down to your vision of how you wanted to play and the kind of players you wanted for Roger Keane Dundee United. -

Las Cuatro Estaciones De Antonio Conte

CLUBPERARNAU P 45 LAS CUATRO ESTACIONES DE ANTONIO CONTE Agustín Galán Antonio Conte ha conseguido en sólo una temporada implantar su propio estilo en el Chelsea, una tarea siempre complicada en el tradicionalista ecosistema de la Premier League. No sólo lo ha logrado, sino que el italiano también ha conseguido marcar la pauta en la competición hasta el punto de que el resto de entrenadores han ido asumiendo su libreto en mayor o menor medida intentando perseguir la estela de unos blues imparables a los que les costó arrancar, pero que después fueron imponiendo su velocidad de crucero a lo largo y ancho de los estadios ingleses, sabiendo adaptarse a las ventajas e inconvenientes que ha ido encontrándose en un año inusual en Stamford Bridge sin competición europea. CLUBPERARNAU P 46 1.- UN VERANO IMPOSIBLE Y CONTINUISTA El anuncio de la llegada de Antonio Con- te al Chelsea era un secreto a voces en la primavera de 2016, hasta el punto de que ambas partes decidieron hacerlo público el 1 de abril para evitar que la especulación fuera a más y perjudicara de alguna mane- ra la labor del técnico al frente de la selec- ción italiana, con la que aún tenía pendiente disputar la Eurocopa de Francia. El Chelsea volvía a apostar por la vía italiana, siendo Con Italia eliminada en los cuartos de fi- el entrenador de Lecce el quinto de esta nal ante Alemania, la incorporación de nacionalidad en asumir el cargo en el club Antonio Conte a su despacho de Cobham londinense en las dos últimas décadas tras se adelantó dos semanas y el Chelsea co- Gianluca Vialli, Claudio Ranieri, Carlo An- menzó a desperezarse. -

Rio Rapids Soccer Club Coaching Education Library

Rio Rapids Soccer Club Coaching Education Library Contact Ray Nause at [email protected] or 505-417-0610 to borrow from the library. Click on the item name for more detailed information. Format Item Author Date Loan Status 4-4-2 vs 4-3-3: An in-depth look at Jose Book Mourinho’s 4-3-3 and how it compares Michele Tossani 2009 Available to Alex Ferguson’s 4-4-2 A Nation of Wimps: The High Cost of Book Hara Estroff Marano 2008 Available Invasive Parenting Book Ajax Training Sessions Jorrit Smink 2004 Available Book Attacking Soccer – A Tactical Analysis Massimo Lucchesi 2001 Available Basic Training - Techniques and Tactics Success in Soccer, Book for Developing the Serious Player - 2002 Available Norbert Vieth Ages 6-14 - Volume 1 Beckham – Both Feet on the Ground: An David Beckham with Book 2003 Available Autobiography Tom Watt Best Practices for Coaching Soccer in the United States Soccer Book 2006 Available United States Federation Bobby Robson: High Noon - A Year at Book Jeff King 1997 Available Barcelona Bounce: Mozart, Federer, Picasso, Book Matthew Syed 2010 Available Beckham, and the Science of Success Challenger’s Competitive Team Training Book Challenger Sports 2004 Available Guide Challenger’s Parent Coach Coaching Book Challenger Sports Unknown Available Guide Book Challenger’s Top 100 Soccer Practices Challenger Sports 2004 Available Coaching for Teamwork – Winning Book Concepts for Business in the Twenty-First Vince Lombardi 1996 Available Century Book The Education of a Coach David Halberstam 2005 Available Book FUNino – -

Mundiales.Pdf

Dr. Máximo Percovich LOS CAMPEONATOS MUNDIALES DE FÚTBOL. UNA FORMA DIFERENTE DE CONTAR LA HISTORIA. - 1 - Esta obra ha sido registrada en la oficina de REGISTRO DE DERECHOS DE AUTOR con sede en la Biblioteca Nacional Dámaso Antonio Larrañaga, encontrándose inscripta en el libro 33 con el Nº 1601 Diseño y edición: Máximo Percovich Diseño y fotografía de tapa: Máximo Percovich. Contacto con el autor: [email protected] - 2 - A Martina Percovich Bello, que según muchos es mi “clon”. A Juan Manuel Nieto Percovich, mi sobrino y amigo. A Margarita, Pedro y mi sobrina Lucía. A mis padres Marilú y Lito, que hace años que no están. A mi tía Olga Percovich Aguilar y a Irma Lacuesta Méndez, que tampoco están. A María Calfani, otra madre. A Eduardo Barbat Parffit, mi maestro de segundo año. A todos quienes considero mis amigos. A mis viejos maestros, profesores y compañeros de la escuela y el liceo. A la Generación 1983 de la Facultad de Veterinaria. A Uruguay Nieto Liszardy, un sabio. A los ex compañeros de transmisiones deportivas de Delta FM en José P. Varela. A la memoria de Alberto Urrusty Olivera, el “Vasco”, quien un día me escuchó comentar un partido por la radio y nunca más pude olvidar su elogio. A la memoria del Padre Antonio Clavé, catalán y culé recalcitrante, A Homero Mieres Medina, otro sabio. A Jorge Pasculli. - 3 - - 4 - Máximo Jorge Percovich Esmaiel, nacido en la ciudad de Minas –Lavalleja, Uruguay– el 14 de mayo de 1964, es un Médico Veterinario graduado en la Universidad de la República Oriental del Uruguay, actividad esta que alterna con la docencia. -

P18 Layout 1

THURSDAY, APRIL 24, 2014 SPORTS United break with tradition in Moyes sacking LONDON: By sacking David Moyes as ever, the board decided that it could no in November 1986, Moyes’s job was to The emphasis now will be on finding “I think there is a way of decency manager after less than a season in longer stand by and watch Ferguson’s take command of the juggernaut that a manager with a proven track-record at with dealing with people,” he said. charge, Manchester United contravened empire crumble, regardless of the his predecessor had built. the highest level of the European game “Football managers now just get tossed the principles explicitly laid out by his instructions he had left behind. Ferguson hoped the structures he capable of undoing the damage that around, chucked about, disregarded, illustrious predecessor Alex Ferguson. Had Moyes seen out his six-year con- had put in place would allow Moyes- Moyes has inflicted. While Ryan Giggs rubbished. Decent men, good men, just Ferguson was granted a three-and-a- tract, he would have become United’s who failed to win a trophy in his 11 will take charge of the first team in the get thrown away. And that’s not just half-year grace period before winning third longest-serving post-war manager, years at Everton-to slot seamlessly into interim, the names being linked with David Moyes, that’s all the way through the first of his 38 trophies as United behind only Ferguson and United’s oth- place, thereby enabling United to main- the job on a permanent basis-Louis van football.” manager, in 1990, and he expected his er great Scottish figurehead, Matt tain a tradition of appointing promising, Gaal, Diego Simeone, Jurgen Klopp- The move also met with disapproval successor, who he hand-picked himself, Busby. -

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout Billie usually foretaste heinously or cultivate roguishly when contradictive Friedrick buncos ne'er and banally. Paludal Hersh never premiere so anyplace or unrealize any paragoge intemperately. Shriveled Abdulkarim grounds, his farceuses unman canoes invariably. There is one penalty shootout, however, that actually made me laugh. After Mane scored, Liverpool nearly followed up with a second as Fabinho fired just wide, then Jordan Henderson forced a save from Kepa Arrizabalaga. Luckily, I could do some movements. Premier League play without conceding a goal. Robben with another cross to Mueller identical from before. Drogba also holds the record for most goals scored at the new Wembley Stadium with eight. Of course, you make saves as a goalkeeper, play the ball from the back, catch a corner. Too many images selected. There is no content available yet for your selection. Sorry, images are not available. Next up was Frank Lampard and, of course, he scored with a powerful hit. Extra small: Most smartphones. Preview: St Mirren vs. Find general information on life, culture and travel in China through our news and special reports or find business partners through our online Business Directory. About two thirds of the voters decided in favor of the proposition. FC Bayern Muenchen München vs. Frank Lampard of Chelsea celebrates scoring the opening goal from the penalty spot with teammate Didier Drogba during the Barclays Premier League. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Eintracht Frankfurt on Thursday. Their second penalty was more successful, but hardly signalled confidence from the spot, it all looked like Burghausen left their heart on the pitch and had nothing to give anymore. -

Fired-Up Mourinho Renews Battle with Conte's Chelsea

Sports FRIDAY, APRIL 14, 2017 Northern giants clash with EPL return in sight MANCHESTER: It will be a Premier League game in all but name when Newcastle United face Leeds United at St James’ Park today, with two of the traditional powers of northern English football seeking a return to the top flight. Newcastle, relegated from the Premier League last season, are second in the Championship and well placed for an immediate return, while Leeds, in fifth place, will look to get through the play-offs and end their 13 years in the lower divisions. The two clubs have histories that make them known well beyond their pas- sionate local support bases. Both are both former champions of England, with Leeds having won the last title before the creation of the Premier League in 1992. They have both won European trophies - Leeds twice capturing the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup, the forerunner MANCHESTER: Manchester United’s Portuguese manager Jose Mourinho (left) walks away as his players of today’s Europa League, while Newcastle won the same com- take part in a team training session at their Carrington base in Manchester, north west England. —AFP petition in 1969. In more recent years, the clubs have featured in the Champions League, which Newcastle’s Spanish manager Rafa Benitez won as manager of Liverpool in 2005. While Benitez and Newcastle have quickly healed the pain of relega- Fired-up Mourinho renews tion with a strong challenge for direct promotion this season, life outside the Premier League has been tough for Leeds. The financial troubles which caused the team’s relegation battle with Conte’s Chelsea from the top flight in 2004 were also to blame for a slump into the third tier (League One) for three seasons, until they returned to the Championship in 2007. -

El Efecto Simeone

El efecto Simeone La motivación como estrategia Primera edición en esta colección: abril de 2013 © Diego Pablo Simeone, 2013 © del prólogo: Luis Aragonés © fotografías del interior: cortesía de la familia Simeone © de la presente edición: Plataforma Editorial, 2013 © de la presente edición: Big Rights S.L., 2013 Editor: Santi García Bustamante Plataforma Editorial c/ Muntaner, 269, entlo. 1.ª – 08021 Barcelona Tel.: (+34) 93 494 79 99 – Fax: (+34) 93 419 23 14 www.plataformaeditorial.com [email protected] Fotografía de cubierta: Ángel Gutiérrez Luque Depósito Legal: B. 10.140-2013 ISBN Digital: 978-84-15880-25-7 Reservados todos los derechos. Quedan rigurosamente prohibidas, sin la autorización escrita de los titulares del copyright, bajo las sanciones establecidas en las leyes, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, comprendidos la reprografía y el tratamiento informático, y la distribución de ejemplares de ella mediante alquiler o préstamo públicos. Si necesita fotocopiar o reproducir algún fragmento de esta obra, diríjase al editor o a CEDRO (www.cedro.org). A Giovanni, Gianluca y Giuliano por las horas que les he restado para poder realizar mi trabajo. Y a todas aquellas personas que de alguna manera han transitado conmigo por el camino hermoso del fútbol, mi pasión. «Estaré loco pero aún vivo del corazón.» Diego Simeone Contenido Cubierta Portadilla Créditos Dedicatoria Cita Presentación Prólogo 1. En esto creo 2. El corazón como guía 3. Gestionando equipos humanos 4. La vida y el fútbol 5. Diego Pablo Simeone. El «Cholo» 6. Palabra de Simeone Agradecimientos La opinión del lector Otros títulos de la colección ¿Dónde está el límite? Presentación Por qué y cómo se ha elaborado este libro E n nuestra continua búsqueda de temas auténticos y con sentido para la colección Plataforma Actual, hace tiempo en la editorial decidimos analizar la figura de Diego Simeone, exfutbolista y actual entrenador del Atlético de Madrid.