How We Think About Disparity and What We Get Wrong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Members Nominated for Election As Select Committee Chairs

MEMBERS NOMINATED FOR ELECTION AS SELECT COMMITTEE CHAIRS Only the first 15 names of a candidate’s own party validly submitted in support of a candidature are printed except in the case of committees with chairs allocated to the Scottish National Party when only the first five such names are printed. Candidates for the Backbench Business Committee require signatures of between 20 and 25 Members, of whom no fewer than 10 shall be members of a party presented in Her Majesty’s Government and no fewer than 10 shall be members of another party or no party. New nominations are marked thus* UP TO AND INCLUDING TUESDAY 21 JANUARY 2020 BACKBENCH BUSINESS COMMITTEE Candidate Ian Mearns Supporters (Government party): Bob Blackman, Mr William Wragg, Damien Moore, Robert Halfon, Mr Ian Liddell-Grainger, John Howell, John Lamont, Kevin Hollinrake, James Cartlidge, Bob Seely Supporters (other parties): Mike Amesbury, Kate Green, Bambos Charalambous, Martin Docherty-Hughes, Ronnie Cowan, Pete Wishart, Brendan O’Hara, Allan Dorans, Patricia Gibson, Kirsten Oswald, Feryal Clark, Tonia Antoniazzi, Yasmin Qureshi, Mr Tanmanjeet Singh Dhesi Relevant interests declared None DEFENCE Candidate James Gray Supporters (own party): Jack Brereton, Mr William Wragg, Bob Blackman, Angela Richardson, Darren Henry, Sir Desmond Swayne, Anne Marie Morris, Jane Hunt, Steve Double, Gary Sambrook, Julie Marson, David Morris, Craig Whittaker, Mr Robert Goodwill, Adam Afriyie Supporters (other parties): Pete Wishart, Christian Matheson, Yasmin Qureshi, Chris Bryant Relevant -

Coronavirus (COVID-19): the Effects on the Legal Profession

House of Commons Justice Committee Coronavirus (COVID-19): the impact on the legal professions in England and Wales Seventh Report of Session 2019–21 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 22 July 2020 HC 520 Published on 3 August 2020 by authority of the House of Commons Justice Committee The Justice Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Ministry of Justice and its associated public bodies (including the work of staff provided for the administrative work of courts and tribunals, but excluding consideration of individual cases and appointments, and excluding the work of the Scotland and Wales Offices and of the Advocate General for Scotland); and administration and expenditure of the Attorney General’s Office, the Treasury Solicitor’s Department, the Crown Prosecution Service and the Serious Fraud Office (but excluding individual cases and appointments and advice given within government by Law Officers). Current membership Sir Robert Neill MP (Conservative, Bromley and Chislehurst) (Chair) Paula Barker MP (Labour, Liverpool, Wavertree) Richard Burgon MP (Labour, Leeds East) Rob Butler MP (Conservative, Aylesbury) James Daly MP (Conservative. Bury North) Sarah Dines MP (Conservative, Derbyshire Dales) Maria Eagle MP (Labour, Garston and Halewood) John Howell MP (Conservative, Henley) Kenny MacAskill MP (Scottish National Party, East Lothian) Kieran Mullan MP (Conservative, Crewe and Nantwich) Andy Slaughter MP (Labour, Hammersmith) The following were also Members of the Committee during this session. Ellie Reeves MP (Labour, Lewisham West and Penge) and Ms Marie Rimmer MP (Labour, St Helens South and Whiston) Powers © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2019. -

Financial Year 2017-18 (PDF)

Envelope (Inc. Paper (Inc. Postage (Inc. Grand Total Member of Parliament's Name Parliamentary Constituency VAT) VAT) VAT) Adam Afriyie MP Windsor £188.10 £160.85 £2,437.50 £2,786.45 Adam Holloway MP Gravesham £310.74 £246.57 £3,323.75 £3,881.06 Adrian Bailey MP West Bromwich West £87.78 £0.00 £1,425.00 £1,512.78 Afzal Khan MP Manchester Gorton £327.49 £636.95 £6,885.00 £7,849.44 Alan Brown MP Kilmarnock and Loudoun £238.29 £203.34 £2,463.50 £2,905.13 Alan Mak MP Havant £721.71 £385.00 £7,812.50 £8,919.21 Albert Owen MP Ynys Mon £93.11 £86.12 £812.50 £991.73 Alberto Costa MP South Leicestershire £398.43 £249.23 £3,802.50 £4,450.16 Alec Shelbrooke MP Elmet and Rothwell £116.73 £263.57 £2,240.00 £2,620.30 Alex Burghart MP Brentwood & Ongar £336.60 £318.63 £3,190.00 £3,845.23 Alex Chalk MP Cheltenham £476.58 £274.30 £4,915.00 £5,665.88 Alex Cunningham MP Stockton North £182.70 £154.09 £1,817.50 £2,154.29 Alex Norris MP Nottingham North £217.42 £383.88 £2,715.00 £3,316.30 Alex Sobel MP Leeds North West £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 Alison McGovern MP Wirral South £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 £0.00 Alister Jack MP Dumfries and Galloway £437.04 £416.31 £4,955.50 £5,808.85 Alok Sharma MP Reading West £374.19 £399.80 £4,332.50 £5,106.49 Rt Hon Alun Cairns MP Vale of Glamorgan £446.30 £105.53 £8,305.00 £8,856.83 Amanda Milling MP Cannock Chase £387.40 £216.72 £4,340.00 £4,944.12 Andrea Jenkyns MP Morley & Outwood £70.14 £266.82 £560.00 £896.96 Andrew Bowie MP W Aberdeenshire & Kincardine £717.92 £424.42 £7,845.00 £8,987.34 Andrew Bridgen MP North West Leicestershire -

3000 Golden Valley

XO TECHNOLOGY INNOVATION ENTERPRISE CULTURE ENTERPRISE CULTURE INNOVATION TECHNOLOGY ISSUE 01 MARCH 2020 PUBLISHED BY CHELTENHAM BOROUGH COUNCIL GOLDEN 3000 VALLEY Welcome to the garden community THE GOLDEN VALLEY DEVELOPMENT THE GOLDEN VALLEY NEW of the future HOMES Homes England put their stake in the ground CYBER CENTRAL UK The UK capital of cyber security in Gloucestershire ISSUE 01 ISSUE MARCH 2020 MARCH Madeline Howard Director Cheltenham Cyber XO | MARCH 2020 | 46 THE GOLDEN VALLEY DEVELOPMENT | 01 CREDITS Published by Cheltenham Borough 04 22 Council Municipal Offices Promenade WHAT IS CYBER CENTRAL? THE OUTPOST Cheltenham Living and working in the heart of Businesses in the South West GL50 9SA 01242 262626 ‘The Golden Valley Development’. welcome the opportunities and growth that Cyber Central will bring. Contributors Ian Collinson Senior Manager Tim Atkins Homes England Managing Director Place & Growth Paul Coles Cheltenham Borough English Regions Director 08 26 Council BT Group WORK, REST AND PLAY HIGH FLYERS Madeline Howard Chris Lau Director Head of Inward Investment What is a Garden Community? Nick Sturge MBE explains what it CyNam Gfirst LEP takes to drive innovation forward. Chris Ensor Matt Warman MP DCMS Deputy Director Digital Minister National Cyber Security Centre Neil Hopwood Programme Manager Nick Surge Cyber Central Founder Engine Shed Jamie Fox 11 30 Programme Consultant Paul Fletcher Cyber Central Chief Executive Officer 3,000 HOMES WITH HEART A POWERFUL PARTNERSHIP British Computer Society Amanda Keane Ian Collinson defines some The private and public sector (BCS) Project Support Cyber Central key landmarks for The Golden have joined forces to transform Bruce Gregory Valley Development. -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

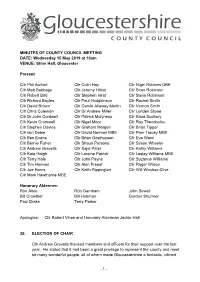

Minutes Template

MINUTES OF COUNTY COUNCIL MEETING DATE: Wednesday 15 May 2019 at 10am VENUE: Shire Hall, Gloucester Present Cllr Phil Awford Cllr Colin Hay Cllr Nigel Robbins OBE Cllr Matt Babbage Cllr Jeremy Hilton Cllr Brian Robinson Cllr Robert Bird Cllr Stephen Hirst Cllr Steve Robinson Cllr Richard Boyles Cllr Paul Hodgkinson Cllr Rachel Smith Cllr David Brown Cllr Carole Allaway Martin Cllr Vernon Smith Cllr Chris Coleman Cllr Dr Andrew Miller Cllr Lynden Stowe Cllr Dr John Cordwell Cllr Patrick Molyneux Cllr Klara Sudbury Cllr Kevin Cromwell Cllr Nigel Moor Cllr Ray Theodoulou Cllr Stephen Davies Cllr Graham Morgan Cllr Brian Tipper Cllr Iain Dobie Cllr David Norman MBE Cllr Pam Tracey MBE Cllr Ben Evans Cllr Brian Oosthuysen Cllr Eva Ward Cllr Bernie Fisher Cllr Shaun Parsons Cllr Simon Wheeler Cllr Andrew Gravells Cllr Sajid Patel Cllr Kathy Williams Cllr Kate Haigh Cllr Loraine Patrick Cllr Lesley Williams MBE Cllr Terry Hale Cllr John Payne Cllr Suzanne Williams Cllr Tim Harman Cllr Alan Preest Cllr Roger Wilson Cllr Joe Harris Cllr Keith Rippington Cllr Will Windsor-Clive Cllr Mark Hawthorne MBE Honorary Aldermen Ron Allen Rob Garnham John Sewell Bill Crowther Bill Hobman Gordon Shurmer Paul Drake Terry Parker Apologies: Cllr Robert Vines and Honorary Alderman Jackie Hall 25. ELECTION OF CHAIR Cllr Andrew Gravells thanked members and officers for their support over the last year. He stated that it had been a great privilege to represent the county and meet so many wonderful people, all of whom made Gloucestershire a fantastic, vibrant - 1 - Minutes subject to their acceptance as a correct record at the next meeting and successful place. -

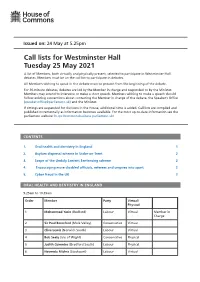

View Call Lists: Westminster Hall PDF File 0.05 MB

Issued on: 24 May at 5.25pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 25 May 2021 A list of Members, both virtually and physically present, selected to participate in Westminster Hall debates. Members must be on the call list to participate in debates. All Members wishing to speak in the debate must be present from the beginning of the debate. For 30-minute debates, debates are led by the Member in charge and responded to by the Minister. Members may attend to intervene or make a short speech. Members wishing to make a speech should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office ([email protected]) and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to-date information see the parliament website: https://commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ CONTENTS 1. Oral health and dentistry in England 1 2. Asylum dispersal scheme in Stoke-on-Trent 2 3. Scope of the Unduly Lenient Sentencing scheme 2 4. Encouraging more disabled officials, referees and umpires into sport 2 5. Cyber fraud in the UK 3 ORAL HEALTH AND DENTISTRY IN ENGLAND 9.25am to 10.55am Order Member Party Virtual/ Physical 1 Mohammad Yasin (Bedford) Labour Virtual Member in Charge 2 Sir Paul Beresford (Mole Valley) Conservative Virtual 3 Clive Lewis (Norwich South) Labour Virtual 4 Bob Seely (Isle of Wight) Conservative Physical 5 Judith Cummins (Bradford South) Labour Physical 6 -

(A) Ex-Officio Members

Ex-Officio Members of Court (A) EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS (i) The Chancellor His Royal Highness The Earl of Wessex (ii) The Pro-Chancellors Sir Julian Horn-Smith Mr Peter Troughton Mr Roger Whorrod (iii) The Vice-Chancellor Professor Dame Glynis Breakwell (iv) The Treasurer Mr John Preston (v) The Deputy Vice-Chancellor and Pro-Vice-Chancellors Professor Bernie Morley, Deputy Vice-Chancellor & Provost Professor Jeremy Bradshaw, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (International & Doctoral) Professor Jonathan Knight, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Research) Professor Peter Lambert, Pro-Vice-Chancellor (Learning & Teaching) (vi) The Heads of Schools Professor Veronica Hope Hailey, Dean and Head of the School of Management Professor Nick Brook, Dean of the Faculty of Science Professor David Galbreath, Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Professor Gary Hawley, Dean of the Faculty of Engineering and Design (vii) The Chair of the Academic Assembly Dr Aki Salo (viii) The holders of such offices in the University not exceeding five in all as may from time to time be prescribed by the Ordinances Mr Mark Humphriss, University Secretary Ms Kate Robinson, University Librarian Mr Martin Williams, Director of Finance Ex-Officio Members of Court Mr Martyn Whalley, Director of Estates (ix) The President of the Students' Union and such other officers of the Students' Union as may from time to time be prescribed in the Ordinances Mr Ben Davies, Students' Union President Ms Chloe Page, Education Officer Ms Kimberley Pickett, Activities Officer Mr Will Galloway, Sports -

A Guide to the Government for BIA Members

A guide to the Government for BIA members Correct as of 29 November 2018 This is a briefing for BIA members on the Government and key ministerial appointments for our sector. It has been updated to reflect the changes in the Cabinet following the resignations in the aftermath of the government’s proposed Brexit deal. The Conservative government does not have a parliamentary majority of MPs but has a confidence and supply deal with the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). The DUP will support the government in key votes, such as on the Queen's Speech and Budgets. This gives the government a working majority of 13. Contents: Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector .......................................................................................... 2 Ministerial brief for the Life Sciences.............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Theresa May’s team in Number 10 ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 Ministerial and policy maker positions in the new Government relevant to the life sciences sector* *Please note that this guide only covers ministers and responsibilities pertinent to the life sciences and will be updated as further roles and responsibilities are announced. -

Pre-Legislative Scrutiny: Draft Personal Injury Discount Rate Clause

House of Commons Justice Committee Pre-legislative scrutiny: draft personal injury discount rate clause Third Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 28 November 2017 HC 374 Published on 30 November 2017 by authority of the House of Commons Justice Committee The Justice Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Ministry of Justice and its associated public bodies (including the work of staff provided for the administrative work of courts and tribunals, but excluding consideration of individual cases and appointments, and excluding the work of the Scotland and Wales Offices and of the Advocate General for Scotland); and administration and expenditure of the Attorney General’s Office, the Treasury Solicitor’s Department, the Crown Prosecution Service and the Serious Fraud Office (but excluding individual cases and appointments and advice given within government by Law Officers). Current membership Robert Neill MP (Conservative, Bromley and Chislehurst) (Chair) Mrs Kemi Badenoch MP (Conservative, Saffron Walden) Ruth Cadbury MP (Labour, Brentford and Isleworth) Alex Chalk MP (Conservative, Cheltenham) Bambos Charalambous MP (Labour, Enfield, Southgate) Mr David Hanson MP (Labour, Delyn) John Howell MP (Conservative, Henley) Gavin Newlands MP (Scottish National Party, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Laura Pidcock MP (Labour, North West Durham) Victoria Prentis MP (Conservative, Banbury) Ellie Reeves MP (Labour, Lewisham West and Penge) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 691 15 March 2021 No. 190 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 15 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP COP26 PRESIDENT—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Kwasi Kwarteng, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon.