Examining the Evolution of Urban Multipurpose Facilities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

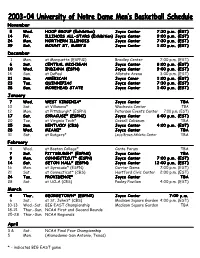

04 Mbb Schedule

2003-04 University of Notre Dame Men’s Basketball Schedule November 5 Wed. HOOP GROUP (Exhibition) Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 14 Fri. ILLINOIS ALL-STARS (Exhibition) Joyce Center 9:00 p.m. (EST) 24 Mon. NORTHERN ILLINOIS Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 29 Sat. MOUNT ST. MARY’S Joyce Center 1:00 p.m. (EST) December 1 Mon. at Marquette (ESPN2) Bradley Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 6 Sat. CENTRAL MICHIGAN Joyce Center 8:00 p.m. (EST) 10 Wed. INDIANA (ESPN) Joyce Center 9:00 p.m. (EST) 14 Sun. at DePaul Allstate Arena 3:00 p.m. (EST) 21 Sun. AMERICAN Joyce Cener 1:00 p.m. (EST) 23 Tue. QUINNIPIAC Joyce Center 7:30 p.m. (EST) 28 Sun. MOREHEAD STATE Joyce Center 1:00 p.m. (EST) January 7 Wed. WEST VIRGINIA* Joyce Center TBA 10 Sat. at Villanova* Wachovia Center TBA 12 Mon. at Pittsburgh* (ESPN) Petersen Events Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 17 Sat. SYRACUSE* (ESPN2) Joyce Center 6:00 p.m. (EST) 20 Tue. at Virginia Tech* Cassell Coliseum TBA 25 Sun. KENTUCKY (CBS) Joyce Center 4:00 p.m. (EST) 28 Wed. MIAMI* Joyce Center TBA 31 Sat. at Rutgers* Louis Brown Athletic Center TBA February 4 Wed. at Boston College* Conte Forum TBA 7 Sat. PITTSBURGH* (ESPN2) Joyce Center TBA 9 Mon. CONNECTICUT* (ESPN) Joyce Center 7:00 p.m. (EST) 14 Sat. SETON HALL* (ESPN) Joyce Center 12:00 p.m. (EST) 16 Mon. at Syracuse* (ESPN) Carrier Dome 7:00 p.m. -

Procane NBA U Hisory

HURRICANES IN THE DRAFT UM PLAYERS SELECTED IN THE NBA DRAFT PLAYER TEAM YEAR ROUND-OVERALL PICK Dick Miani New York Knickerbockers 1956 Knicks’ 10th selection Mike McCoy Detroit Pistons 1963 3rd Round-21st overall Rick Barry San Francisco Warriors 1965 1st Round-2nd overall Mike Wittman St. Louis Hawks 1967 5th Round-49th overall Rusty Parker Atlanta Hawks 1968 5th Round-61st overall Bill Soens Philadelphia 76ers 1968 11th Round-145th overall Don Curnutt New York Knickerbockers 1970 10th Round-170th overall Wayne Canady Portland Trail Blazers 1970 15th Round-218th overall Willie Allen Baltimore Bullets 1971 4th Round-60th overall Tito Horford Milwaukee Bucks 1988 2nd Round-39th overall Joe Wylie Los Angeles Clippers 1991 2nd Round-38th overall Constantin Popa Los Angeles Clippers 1995 2nd Round-53rd overall Tim James Miami Heat 1999 1st Round-25th overall John Salmons San Antonio Spurs 2002 1st Round-26th overall James Jones Indiana Pacers 2003 2nd Round-49th overall Guillermo Diaz Los Angeles Clippers 2006 2nd Round-52nd overall Jack McClinton San Antonio Spurs 2009 2nd Round-51st overall 155 In 1999, TIM JAMES was selected in the first round of the NBA Draft by the Miami Heat. UM PLAYERS SELECTED IN THE ABA DRAFT PLAYER TEAM YEAR ROUND Mike Wittman Anaheim Amigos 1967 12th Round Bill Soens New York Nets 1968 10th Round Rusty Parker Oakland Oaks 1968 8th Round Don Curnutt Indiana Pacers 1970 7th Round Willie Allen Miami Floridians 1971 12th Round JOHN SALMONS averaged 18.1 points, 4.4 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game for the JACK McCLINTON was selected in the second round of the 2009 NBA Draft by the San Chicago Bulls during the 2009 NBA Playoffs, including a 35-point outing versus the Celtics. -

Passive Participation: the Selling of Spectacle and the Construction of Maple Leaf Gardens, 1931

Sport History Review, 2002, 33, 35-50 PASSIVE PARTICIPATION 35 © 2002 Human Kinetics Publishers, Inc. Passive Participation: The Selling of Spectacle and the Construction of Maple Leaf Gardens, 1931 Russell Field In 1927, Conn Smythe, a Toronto businessman and hockey enthusi- ast, organized a group to purchase Toronto’s entry in the National Hockey League (NHL). Operating out of the fifteen-year-old Arena Gardens, the St. Patricks (who Smythe renamed Maple Leafs) had for years been only moderately successful both on the ice and at the cashbox. Compounding Smythe’s local and competitive circumstances was the changing nature of the NHL in the mid 1920s. Beginning in 1924, the Canadian-based NHL clubs reaped the short-term benefits of expansion fees paid by the new American teams, but the latter’s greater capital resources and newer, larger playing facilities soon shifted the economic balance of power within the “cartel” south of the border.1 As Thompson and Seager note of this period: “Canadian hockey was revolutionized by American money.”2· Despite the Maple Leafs’ bleak economic circumstances, Smythe had big dreams for himself and his hockey team. In attempting to realize his vision, he built Canada’s best-known sports facility, Maple Leaf Gardens, managed the Maple Leafs into one of the NHL’s wealthiest clubs, and assumed majority ownership of the team. The economic and cultural impact of the major NHL-inspired arena projects of the 1920s and early 1930s—the Montreal Forum, New York’s Madison Square Garden, Boston Garden, Chicago Stadium, the Detroit Olympia, as well as Maple Leaf Gardens—has received little attention among scholarly contributions to the study of sport.3 However, there has been greater interest in the politics of arena and stadium construction, and work by scholars such as John Bale and Karl Raitz has helped to define and explore the notion of arenas and stadiums as sport spaces.4 Adding a fur- ther temporal context to these issues then, allows changes over time to be meaningfully explored. -

University of Cincinnati News Record. Friday, February 2, 1968. Vol. LV

\LI T , Vjb, i ;-/ Cineinneti, Ohio; Fr~day, February 2, 1968' No. 26 Tickets. For Mead Lectilres ..". liM,ore.ea. H' d''Sj·.L~SSI., .' F"eet...-< II Cru~cialGame.~ Gr~atestNeed'Of Young; Comments -MargQret Mead Are Ava'ilab'le by Alter Peerless '\... that the U.S. was fighting an evil Even before the Bearcatsget enemy, but now-people can see "In the, past fifty years there a chance to recover from the'" for themselves that in' war both has been too much use of feet, sides kill and mutilate other peo- _ shell shock of two conference and not enough use' of heads," ple. road loses in a row, tihey baY~,to -said Dr: Margaret Mead, inter- Another reason this generation play 'the most 'Crucial' game' of nationally kn'own· anthropologist, is unhappy is because the num- in her lecture at the YMCA.'last bers involved are smaller. In the yea!,~at Louisville. Tuesday., . Wednesday n i gh t's Bradley World War II, the Americans had Dr. Mead .spoke on "College no sympathy for war victims. game goes down as' a wasted ef- Students' Disillusionment: Viet- They could not comprehend the fort. Looking strong at the begin- nam War and National Service." fact that six' .million Jews were· ningthe 'Cats faded in the final She said that this is not the first ' killed, or that an entire city was period when 'young people have wiped out. The horror of World minutes, missing several shots. , demonstrated for 'good causes. Jim Ard played welleonsidering War II was so great, America There have' been peace marches, could not react to it. -

Boston Guide

what to do U wherewher e to go U what to see July 13–26, 2009 Boston FOR KIDS INCLUDING: New England Aquarium Boston Children’s Museum Museum of Science NEW WEB bostonguide.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! oyster perpetual gmt-master ii The moon landing 40th anniversary. See how it Media Sponsors: OFFICIALROLEXJEWELER JFK ROLEX OYSTER PERPETUAL AND GMT-MASTER II ARE TRADEMARKS. began at the JFK Presidential Library and Museum. Columbia Point, Boston. jfklibrary.org StunningCollection of Murano Glass N_Xc\ NXkZ_ E\n <e^cXe[ 8hlXi`ld J`dfej @D8O K_\Xki\ Pfli e\ok Furnishings, Murano Glass, Sculptures, Paintings, X[m\ekli\ Tuscan Leather, Chess Sets, Capodimonte Porcelain Central Wharf, Boston, MA www.neaq.org | 617-973-5206 H:K:CIN C>C: C:L7JGN HIG::I s 7DHIDC B6HH68=JH:IIH XnX`kj telephone s LLL <6AA:G>6;ADG:CI>6 8DB DAVID YURMAN JOHN HARDY MIKIMOTO PATEK PHILIPPE STEUBEN PANERAI TOBY POMEROY CARTIER IPPOLITA ALEX SEPKUS BUCCELLAITI BAUME & MERCIER HERMES MIKIMOTO contents l Jew icia e ff le O r COVER STORY 14 Boston for Kids The Hub’s top spots for the younger set DEPARTMENTS 10 hubbub Sand Sculpting Festival and great museum deals 18 calendar of events 20 exploring boston 20 SIGHTSEEING 30 FREEDOM TRAIL 32 NEIGHBORHOODS 47 MAPS 54 around the hub 54 CURRENT EVENTS 62 ON EXHIBIT 67 SHOPPING 73 NIGHTLIFE 76 DINING on the cover: JUMPING FOR JOY: Kelly and Patrick of Model Kelly and Patrick enjoy the Club Inc. take a break in interactive dance floor in the front of a colorful display Boston Children’s Museum’s during their day of fun at the Kid Power exhibit area. -

Legends Open

LEGENDS OPEN MAY 19, 2014 HURSTBOURNE COUNTRY CLUB, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY THANK YOU for joining the Louisville Sports Commission for its third annual Legends Open, presented by Air Hydro Power. All of us – the staff, board of directors and Legends Open committee members – are very excited about this opportunity to once again honor Kentuckiana’s sporting legends. The Louisville region is fortunate to have a very rich history of legendary sports figures, including the greatest of all time, Muhammad Ali. Because of the Legends’ importance to our community, the Louisville Sports Commission LEGENDS OPEN established the Legends Open as one way in which we can recognize these men and women for their PROGRAM incredible sporting achievements, to help preserve their legacy and encourage each Legend to continue REGISTRATION AND BREAKFAST 9:30 - 10:30 AM to be great Ambassadors for our community. SILENT AUCTION OPENS FOR The Louisville Sports Commission is VIEWING/BIDDING 9:30 AM dedicated to attracting, creating and hosting quality sporting events in the Louisville area that PAIRINGS REVEAL PROGRAM 10:30-11:15 AM increase economic vitality, enhance quality of life, TEE TIME/SHOTGUN START 11:30 AM promote healthy lifestyles and brand Louisville as a great sports town. The Legends Open enables us COCKTAILS AND HORs d’oeuvRES 5:00 - 7:00 PM to further our core mission by acknowledging the important role these athletes and coaches played – AUCTION AND AWARDS RECEPTION 6:00 - 7:30 PM and continue to play – in our community. SILENT AUCTION CLOSES 7:00 PM The Legends Open would not be possible without the support of our local business community. -

Pepperdine Basketball History

PPEPPERDINEEPPERDINE MMEN’SEN’S BBASKETBALLASKETBALL 22018-19018-19 MMEDIAEDIA AALMANACLMANAC Note to the media: Pepperdine University no longer prints traditional media guides. This media almanac, which includes coach and player biographies, season and career statistics and the program’s history and records book, is being published online to assist the media in lieu of a traditional guide. PPEPPERDINEEPPERDINE UUNIVERSITYNIVERSITY SSCHEDULECHEDULE Location .........................................................................Malibu, Calif. 90263 DATE DAY OPPONENT TV TIME Founded ...................................................... 1937 (Malibu Campus in 1972) Nov. 7 Wednesday CS Dominguez Hills TheW.tv 7 p.m. Enrollment ................................................. 8,000 total/3,000 undergraduate Nov. 10 Saturday CSUN TheW.tv 7 p.m. Colors ................................................................................ Blue and Orange Nov. 13 Tuesday at Northern Colorado 7 p.m. MT Affi liation ..............................................................................NCAA Division I Nov. 16 Friday # vs. Towson 8 p.m. ET Conference ............................................................. West Coast Conference Nov. 17 Saturday # vs. TBD TBD President ......................................................................... Andrew K. Benton Nov. 18 Sunday # vs. TBD TBD Athletic Director .................................................................... Dr. Steve Potts Nov. 26 Monday Idaho State TheW.tv 7 p.m. Athletic Department -

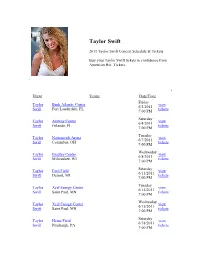

Taylor Swift Tickets in Confidence from American Hot Tickets

Taylor Swift 2011 Taylor Swift Concert Schedule & Tickets Buy your Taylor Swift tickets in confidence from American Hot Tickets. Event Venue Date/Time Friday Taylor Bank Atlantic Center view 6/3/2011 Swift Fort Lauderdale, FL tickets 7:00 PM Saturday Taylor Amway Center view 6/4/2011 Swift Orlando, FL tickets 7:00 PM Tuesday Taylor Nationwide Arena view 6/7/2011 Swift Columbus, OH tickets 7:00 PM Wednesday Taylor Bradley Center view 6/8/2011 Swift Milwaukee, WI tickets 7:00 PM Saturday Taylor Ford Field view 6/11/2011 Swift Detroit, MI tickets 7:00 PM Tuesday Taylor Xcel Energy Center view 6/14/2011 Swift Saint Paul, MN tickets 7:00 PM Wednesday Taylor Xcel Energy Center view 6/15/2011 Swift Saint Paul, MN tickets 7:00 PM Saturday Taylor Heinz Field view 6/18/2011 Swift Pittsburgh, PA tickets 7:00 PM Tuesday Taylor HSBC Arena - NY view 6/21/2011 Swift Buffalo, NY tickets 7:00 PM Wednesday Taylor XL Center - (Formerly Hartford Civic Center) view 6/22/2011 Swift Hartford, CT tickets 7:00 PM Saturday Taylor Gillette Stadium view 6/25/2011 Swift Foxborough, MA tickets 6:00 PM Sunday Taylor Gillette Stadium view 6/26/2011 Swift Foxborough, MA tickets 6:00 PM Thursday Taylor Greensboro Coliseum view 6/30/2011 Swift Greensboro, NC tickets 7:00 PM Friday Taylor Thompson Boling Arena view 7/1/2011 Swift Knoxville, TN tickets 7:00 PM Saturday Taylor KFC Yum! Center view 7/2/2011 Swift Louisville, KY tickets 7:00 PM Time Warner Cable Arena (formerly Charlotte Friday Taylor view Bobcats Arena) 7/8/2011 Swift tickets Charlotte, NC 7:00 PM Saturday -

An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development

Field$ of Dream$: An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development by Aubrey E. Cannuscio B.S., Business Administration, 1991 University of New Hampshire Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1997 @1997 Aubrey E. Cannuscio All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Departme of-Urban Studies and Planning August 1, 1997 Certified by: Timothy Riddiough A sistant Professor of Real Estate Finance Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: William C. Wheaton Chairman, Interdepartmental Degree Program in Real Estate Development a'p) Field$ of Dream$: An Examination of the Effects of Financing Structure on Football Facility Design and Surrounding Real Estate Development by Aubrey E. Cannuscio Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on August 1, 1997 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Real Estate Development ABSTRACT The development of sports facilities comprises a large percentage of municipal investment in infrastructure and real estate. This thesis will analyze, both quantitatively and qualitatively, all football stadiums constructed in the past ten years and how their design, financing and siting impact the surrounding real estate market. The early chapters of this thesis cover general trends and issues in financing, design and development of sports facilities. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abel, Allen (Globe and Mail), 151 Bukovac, Michael, 50 Abgrall, Dennis, 213–14 Bure, Pavel, 200, 203, 237 AHL (American Hockey League), 68, 127 Burns, Pat, 227–28 Albom, Mitch, 105 Button, Jack, and Pivonka, 115, 117 Alexeev, Alexander, 235 American Civil Liberties Union Political Calabria, Pat (Newsday), 139 Asylum Project, 124 Calgary Flames American Hockey League. see AHL (American interest in Klima, 79 Hockey League) and Krutov, 152, 190, 192 Anaheim Mighty Ducks, 197 and Makarov, 152, 190, 192, 196 Anderson, Donald, 26 and Priakin, 184 Andreychuk, Dave, 214 Stanley Cup, 190 Atlanta Flames, 16 Campbell, Colin, 104 Aubut, Marcel, 41–42, 57 Canada European Project, 42–44 international amateur hockey, 4 Stastny brothers, 48–50, 60 pre-WWII dominance, 33 Axworthy, Lloyd, 50, 60 see also Team Canada Canada Cup Balderis, Helmut, 187–88 1976 Team Canada gold, 30–31 Baldwin, Howard, 259 1981 tournament, 146–47 Ballard, Harold, 65 1984 tournament, 55–56, 74–75 Balogh, Charlie, 132–33, 137 1987 tournament, 133, 134–35, 169–70 Baltimore Skipjacks (AHL), 127 Carpenter, Bob, 126 Barnett, Mike, 260 Caslavska, Vera, 3 Barrie, Len, 251 Casstevens, David (Dallas Morning News), 173 Bassett, John F., Jr., 15 Catzman, M.A., 23, 26–27 Bassett, John W.H., Sr., 15 Central Sports Club of the Army (formerly Bentley, Doug, 55 CSKA), 235 Bentley, Max, 55 Cernik, Frank, 81 Bergland,Tim, 129 Cerny, Jan, 6 Birmingham Bulls (formerly Toronto Toros), Chabot, John, 105 19–20, 41 Chalupa, Milan, 81, 114 Blake, Rob, 253 Chara, Zdeno, 263 Bondra, Peter, 260 Chernykh, -

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues

Tax Increment Financing and Major League Venues by Robert P.E. Sroka A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sport Management) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Judith Grant Long, Chair Professor Sherman Clark Professor Richard Norton Professor Stefan Szymanski Robert P.E. Sroka [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6310-4016 © Robert P.E. Sroka 2020 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, John Sroka and Marie Sroka, as well as George, Lucy, and Ricky. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my parents, John and Marie Sroka, for their love and support. Thank you to my advisor, Judith Grant Long, and my committee members (Sherman Clark, Richard Norton, and Stefan Szymanski) for their guidance, support, and service. This dissertation was funded in part by the Government of Canada through a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Doctoral Fellowship, by the Institute for Human Studies PhD Fellowship, and by the Charles Koch Foundation Dissertation Grant. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES v LIST OF FIGURES vii ABSTRACT viii CHAPTER 1. Introduction 1 2. Literature and Theory Review 20 3. Venue TIF Use Inventory 100 4. A Survey and Discussion of TIF Statutes and Major League Venues 181 5. TIF, But-for, and Developer Capture in the Dallas Arena District 234 6. Does the Arena Matter? Comparing Redevelopment Outcomes in 274 Central Dallas TIF Districts 7. Louisville’s KFC Yum! Center, Sales Tax Increment Financing, and 305 Megaproject Underperformance 8. A Hot-N-Ready Disappointment: Little Caesars Arena and 339 The District Detroit 9. -

Amway Center the Orlando Magic Developed the Amway Center, Which Will Compete to Host Major National Events, Concerts and Family Shows

About Amway Center The Orlando Magic developed the Amway Center, which will compete to host major national events, concerts and family shows. The facility opened in the fall of 2010, and is operated by the City of Orlando and owned by the Central Florida community. The Amway Center was designed to reflect the character of the community, meet the goals of the users and build on the legacy of sports and entertainment in Orlando. The building’s exterior features a modern blend of glass and metal materials, along with ever-changing graphics via a monumental wall along one façade. A 180-foot tall tower serves as a beacon amid the downtown skyline. At 875,000 square feet, the new arena is almost triple the size of the old Amway Arena (367,000 square feet). The building features a sustainable, environmentally-friendly design, unmatched technology, featuring 1,100 digital monitors and the tallest, high-definition videoboard in an NBA venue, and multiple premium amenities available to all patrons in the building. Every level of ticket buyer will have access to: the Budweiser Baseline Bar and food court, Club Restaurant, Nutrilite Magic Fan Experience, Orlando Info. Garden, Gentleman Jack Terrace, STUFF’s Magic Castle presented by Club Wyndham and multiple indoor-outdoor spaces which celebrate Florida's climate. Media Kit Table of Contents Enter Legend Public/Private Partnership Fact Sheet By the Numbers Amenities for All Levels Technology LEED: Environmentally-Friendly Corporate Partnerships Jobs in Tough Times Commitment to Parramore Transportation/Parking Concessions Arts and Culture Construction/Design Arena Maps Media Contacts: Joel Glass Heather Allebaugh Tanya Bowley Orlando Magic City of Orlando Amway Center VP/Communications Press Secretary Marketing Manager 407.916-2631 407.246.3423 407.440.7001 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] AmwayCenter.com **For media information: amwaycenter.com/press-room Amway Center: Enter Legend AmwayCenter.com From a vision to blueprints to reality.