Spring 2017 Volume 43 Issue 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediaguide 2021 Duke Baseb

2021 DUKE BASEBALL MEDIA GUIDE QUICK FACTS 1889 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIRST YEAR OF PROGRAM All-Time Program Record ...................... 2,135-1,800-34 SCHEDULE & GAME DAY GUIDE Most Victories in a Season............................. 45 (2018) 3 ROSTER & PRONUNCIATION GUIDE 4-5 BY THE NUMBERS 105 All-ACC Honorees HEAD COACH CHRIS POLLARD & STAFF 6 81 MLB Draft Selections 43 MLB Alumni 13 All-Americans 2020 REVIEW 7 8 NCAA Tournament Appearances 3 College World Series Appearances ANNUAL LEDGER 8-9 DUKE UNIVERSITY ALL-TIME LETTERWINNERS & CAPTAINS 10-16 Location ........................................................Durham, N.C. Founded ......................................1838 as Trinity College ACC CHAMPIONSHIP HISTORY 17 Enrollment .................................................................6,994 Colors ..............................Duke Blue (PMS 287) & White Nickname ......................................................... Blue Devils NCAA CHAMPIONSHIP HISTORY 18 Conference ...................................................................ACC President ...............................................Dr. Vincent Price Athletic Director ................................Dr. Kevin M. White OPPONENT SUMMARY 19-23 CHRIS POLLARD SERIES RESULTS 24-43 HEAD COACH 630-495-3 245-177 96-114 ANNUAL RESULTS All-Time At Duke ACC 44-69 Associate Head Coach ............................. Josh Jordan Assistant Coach ......................................... Jason Stein ALL-TIME STATISTICS 70-73 Pitching Coach .........................................Chris -

The Duke Chronicle

HAVE YOU A LUCKY STUBS THE DUKE CHRONICLE VOLUME XXXII. NUMBEB New S. G. Officers DIKE COLLEG VS RETURN FOR FINAL SERU 147 WOMEN MAY Danny Farrar Wins, GET DEGREES OF!*, Mann T oses First Installed At Formal DUKE UNIVERSITY ~ ™n ^ ^?- tf Council Ball Tonight Diplomas Conferred Early ii June; l.isl of Elicibles For Struggle In Chicago Durham Lad Falls Before Arts and Science Degrees Administration Headed liy Protege of Joe Louis; 11 Below Last Year's Total Tom Southgate Will Be Matulewicz Makes First Presented to Student liod.v Appearance Tonight During Affair TonieM DIPLOMA ORDER That Caroline Miller. I' ALREADY GIVEN it/or prize siulhor whosne WEST VIRGINIA THOMAS SAYS s,.| ..lieilnled for April 1,1.1,a liekele- Only Three Candidates For MEN DEFEATED BALL FORMAL ,„ . jliaiiieeiim Science Degree in Complete L Denver Welch, Micky iilulln -enrl. Till- Iia List Made Public by Deans Les Brown To Furnish Music Lost in First Appearance; For Outstanding Social Pontecarvo Fiwhts Well; Fete ot Year; Chaperons Semi-Finals Tonight For Affair Are Announced CHICAGO, Mss.v 1 Dnke miivc-r- ;ty lield a .31X1 average here tonight candidates aire aa r REIST itfPOINTS 27 MEMBERS OF lieket, No, 1521;a-5 ticket, No. 370; eel, VS. S. Army, Hia ticket, No. 199. NEW COMMITTEE ,oongster; though Blinds, was -veil ahe Mother's Day Carnation Sale sit througlwut the n First Project of Group; DEVILSOVERCOME Final Orders in Tomorrow e Tom Southgate .. all- a- SAINTS; OPPOSE Sklent He aaill thi GEOLOGY COURSE Leland, Aiken Elected To NAVY TOMORROW emy weight lighter B Gain 7-1 Win Over Sl. -

04 Brian Hernandez

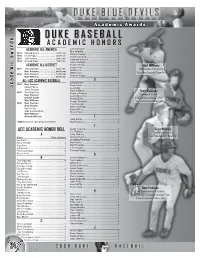

AAcademicc a d e m i c AwardsAw a r d s DUKE BASEBALL s DUKE BASEBALL d ACADEMIC HONORS r Carl Chronister ....................................................1 a ACADEMIC ALL-AMERICA Ben Condon .......................................................1 1972 Richard Bersin ........................... 3rd Team w Clayton Connor....................................................1 1980 Kevin Rigby ...............................2nd Team Darryl Copeland...................................................1 a 1982 Tom Amidon ..............................2nd Team Frederick Cornnell ...............................................1 1994 Sean McNally .............................3rd Team John Courtright ....................................................2 c i ACADEMIC ALL-DISTRICT Stephen Cowie ....................................................4 Matt Williams Charles Cox .........................................................1 2007 Tony Bajoczky ...........................2nd Team m Robbie Cox ..........................................................2 2008 Academic All-District Nate Freiman ..........................2nd Team Three-Time Academic Honor Roll e William Cox ..........................................................2 2008 Nate Freiman ........................... 1st Team Stephen Cupps ....................................................1 d Matt Williams ..........................2nd Team a ALL-ACC ACADEMIC BASEBALL D David Darwin .......................................................1 c 2006 Nate Freiman Doug Davis ..........................................................2 -

Duke University Baseball Media Guide 2012

DUKE UNIVERSITY BASEBALL MEDIA GUIDE 2012 DUKE BASEBALL 2012 MEDIA GUIDE QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS INFORMATION DUKE UNIVERSITY INFORMATION MEDIA INFORMATION 1 Sarkis Ohanian ............................21 Location Durham, N.C. Quick Facts/Table of Contents.......1 Andy Perez ..................................21 Founded 1838 as Trinity College Duke Sports Information ................2 Nick Piscotty ................................22 Enrollment 6,504 Roster ............................................3 Trent Swart ..................................22 Colors Duke Blue (PMS 287) and White Schedule........................................4 Nickname Blue Devils Conference Atlantic Coast (Coastal Division) 2011 IN REVIEW 23 Affiliation NCAA Division I COACHING STAFF 5 Game-by-Game Results ..............23 Stadium Durham Bulls Athletic Park (Grass) & Sean McNally .............................5-6 Overall Statistics ..........................24 Jack Coombs Field (Turf) Sean Snedeker ..............................7 ACC Statistics..............................25 Capacity DBAP (10,000); JCF (2,000) Edwin Thompson ...........................8 Offensive Leaders .......................26 DBAP Dimensions (L to R) 305-371-400-373-327 Kyle Padgett ..................................8 Pitching Leaders ..........................27 JCF Dimensions (L to R) 325-370-400-375-335 President Dr. Richard Brodhead Vice President & Director of Athletics Dr. Kevin White PLAYER BIOS 9 RECORD BOOK 28 Baseball Administrator Brad Berndt Will Piwnica-Worms .......................9 -

The Chronicle Thursday, January 12, 1989 S Duke University Durham, North Carolina Circulation: 15,000 Vol

WELCOME J-FROSH THE CHRONICLE THURSDAY, JANUARY 12, 1989 S DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 84, NO. 72 Page gig set to get Jazz Institute off and running ByMATTSCLAFANI A group of jazz impressarios will be joined Saturday night in Page Auditorium by comedian/ master of ceremonies Steve Allen and actor Clint Eastwood for a concert sponsored by the Thelonius Monk Institute of Jazz. The Institute is scheduled to open in Durham in 1991. Tickets went on sale last week and were sold out by Tuesday, denying most students the chance to buy tickets. Paul Jeffrey, director of jazz studies, said "I wanted to apolo gize to the students" because all the tickets were sold before stu dents had a chance to buy them. SPECIAL TO THE CHRONICLE Thelonius Monk Jr. will per- «.,„. c^„*,„„ , e -,, _•__*_ i*nnt Eastwood BETH ANN FARLEY/THE CHRONICLE form as well as saxophonist Jef The waiting game frey. Other performers include Harris, and Joey DeFrancesco of for the weighty game. Senior engineers Andy Violet (I) and Graham Murphy, keep vigil Clark Terry, formerly of the To- the Miles Davis Orchestra. outside Cameron for the men's basketbaii game against the Tar Heels Jan. 18. night Show Orchestra, Percy The concert is the first perfor- Heath of Modern Jazz Quartet, mance since the announcement recording and film star Barry See CONCERT on page 10 • Fall grades force Cook Student raped in woods near campus From staff reports appeared, forced her into the medium build, Dean said. He The Durham Police Depart woods at the side of the road and was clean-shaven and had a light to sit for two semesters ment and Public Safety are sear raped her. -

CU Boulder Catalog

Welcometo Summer in Boulder The University of Colorado at Boulder offers you the opportunity to earn academic credit, satisfy your curiosity, meet major or minor requirements, and be part of our summer community. Many of CU’s most popular and sought-after courses are offered in Summer Session. Take a course in physics or chemistry, on the apocalypse or Charles Darwin. Whether you’re a college student, a high school student, a teacher, or a visitor to Boulder . there’s something for everyone! We invite you to be a part of our diverse community this summer! With over 500 courses offered this summer, you will find the course that will enrich your creative, professional, cultural, or academic interests. Among the many opportunities offered this summer: • The FIRST (Faculty-in-Residence Summer Term) program brings world-class faculty to the Boulder campus for a unique, multi-disciplinary experience. A complete list of courses begins on page 3. • Maymester offers over 130 courses in a three-week, intensive term that allows you to complete a course and still work, travel, or have an internship. A complete list of courses begins on page 8. • Take advantage of online classes. Experience CU from anywhere. Knowing that our students have busy lives, we are offering three of our most popular classes online. These classes—taught by CU-Boulder faculty—allow you to meet requirements or advance your degree program. As long as you have access to the Internet, you can take one of these classes. See a complete list in the Featured Courses section on page 14. -

FFA New Horizons

, 1991 f. F f I C I A L MAG HE N A T I M Blossoming Horticulture Businesses Desert Storm Calls on FFA f^t--' Advisors --* * > •r.j*"; W^'' r^^ ^4^^ '.^^ '^ ^:''^^- "O'^llf^^- f)siS8nbiay;tiflujj»jJoo ssajppv IZ ON l!LUJ8d VD •uo;sBUJOnx aivd aeejsod sn HH«V8NV ) iijojduoN Jm <g|g(jg3r-:' INTRODUCING A MIRACLE OF MODERN MEDICINE: UNLIMITED OPPORTUNITY. Now that medical specialists are in demand more than ever, there's never been a better time to consider Army Reserve Specialized Training. The Army Reserve can train you in one of a wide variety of medical specialties from Respiratory Specialist, to Practical Nurse, to Pharmacy Specialist. You'll serve part-time, near home, usually one weekend a month, plus two weeks a year. Starting out can be easier than ever, too, through one of our financial assistance programs. Our new Specialized Training for Army Readiness (STAR) program is a great example. If you qualify, we'll help pay for your tuition, books and fees at a local. Army-approved civilian school of your choice. Think about it. Then, think about us. See your Army Reserve Recruiter today. Or callI-800-USA-ARMY FFA NewHoriTons OFFICIAL MA6AZINE OF THE NATIONAL FFA OICANIZATION June-July, 1991 Volume 39 Numbers 12 24 Stars Over Troubled Waters Quality Counts FFA Star Farmers and Agribusinessmen Agricultural electrification winner Matt travel to Europe and see the other side of Shantz and his father believe that quality the international trade issue. service never goes out of style. 14 30 power Plants Two FFA members blossom in the FFA members tell how computers have floriculture business. -

![The American Legion [Volume 112, No. 5 (May 1982)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0456/the-american-legion-volume-112-no-5-may-1982-7080456.webp)

The American Legion [Volume 112, No. 5 (May 1982)]

! TAKE YOUR CHOICE! Navy Loafer Tan Oxford 3ohe Loafer Lt. Blue w. Jute Trim Loafer ESCAPE from the SHOE PINCH! Here's wonderful relief from today's impossibly high shoe prices. And equally comforting escape from today's hot, confining, year-round styles. The tough-but-gentle open mesh nylon keeps its shape but let s feet "breathe" for better-than-barefoot comfort even during summer's hottest days. Long-wearing one-piece rubber heel and sole provides springy comfort with full, firm support. Luxurious pillow-soft foam cushion insoles provide even more comfort! And style? You be the judge! Imagine these handsome, masculine slip-on and tie designs with your casual summer wardrobe. Imagine the cool, smart look of fresh summer colors. Imagine how great they'll feel as your favorite summer shoes for traveling driving, vacationing, or just lazy evenings on the patio! NO RISK! Haband is a conscientious family business, Bit serving American businessmen through the U.S. Mail since 1925. will be proud to show you what we can do i We These are good looking, cool casual shoes that will feel very comfortable and save you money. And, you will be delighted with the service - GUARANTEED! Mesh Shoes 3 19S§ HABAND Co., 265 N. 9th St., Peterson, N.J. 07530 Please send me AVAILABLE SIZES Mesh Shoes as specified I D Width: 614-7 -754-8- I've enclosed $ 854-9-954-10-1014- plus $1 .50 toward 11-1 2-13. | EEE*: 7-8-9-10-11-12-13 i postage & handling. *EEE add $1 per pair GUARANTEE: If upon Color/Style Qty Size V arrival I do not choose to wear them, I may return Brown Loafer them within 30 days for a w. -

24-35 Acad Honors, Jack Coombs, History, Majors, Draft, National And

AAcademiccademic HHonorsonors GTE Academic All-America ACC Academic Honor Roll 1994 Sean McNally, 3B .........................3rd Team (Listed alphabetically) 1982 Tom Amidon, 3B ...........................1st Team A 1980 Kevin Rigby, 2B ............................1st Team Name Times Earned Les Aiello ...................................................................1 GTE Academic All-District David Albright ............................................................3 1994 Sean McNally, 3B .........................3rd Team Jeff Alleva ..................................................................4 1991 David Norman, DH .......................1st Team Thomas Amidon ........................................................ 4 1982 Tom Amidon, 3B ...........................1st Team Daniel Arlen ...............................................................1 1980 Kevin Rigby, 2B ............................1st Team B Tony Bajoczky ...........................................................4 All-ACC Academic Donald Battjer ............................................................1 Kyle Beachamp ......................................................... 1 2007 Tony Bajoczky Doug Bechtold ..........................................................2 Nate Freiman Jeff Becker................................................................. 1 Gabriel Saade Karl Benzio ................................................................1 Matt Williams John Berger ...............................................................2 2006 Nate Freiman -

Washington March Draws Crowds of Demonstrators Conference Offers Education on Rape

THE CHRONICLE MONDAY, APRIL 10, 1989 DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15,000 VOL. 84, NO. 129 Washington march draws crowds of demonstrators By CHRIS ENGDAHL protecting womens' fundamental and KAREN PRICE and basic constitutional WASHINGTON — One of the "reproductive rights." largest crowds ever assembled in Approximately 600,000 pro- Washington gathered near the choice supporters gathered on Washington Monument on the the mall at approximately 10:45 mall in the nation's capital Sun a.m. The grounds surrounding day to march in support of the the Washington Monument were proposed Equal Rights divided so that various delega Amendment, and, perhaps more tions could mass together in urgently, in support of the exist preparation for the march. Offi ing Supreme Court Roe vs. Wade cial estimates numbered the decision. crowd at only 300,000. The march and rally, spon Speakers and singers, includ sored by the National Organiza ing folk singer and political ac tion for Women (NOW), was tivist Holly Near, entertained scheduled purposely only 15 days and inspired the crowd prior to before the Supreme Court is to the scheduled march down the consider a Missouri case that spectator-lined mall to the Capi could overturn the Roe vs. Wade tol. case decision. This landmark College students made up a 1973 case effectively gives large portion of the crowd. CHAD HOOD/THE CHRONICLE women the right to decide Universities from all over the The National Archives provide a backdrop for demonstrators raising their American voices. whether or not to have an abor country were represented, and tion. -

Local Clubs to Participate In. Anti-War Strike

• tf'AO FOREST COLLEGE LIBRARY PATRONIZE ST.AND BY OLD GOLD AND BLACK THESE MERCHANTS ADVERTISERS THEY STAND BY YOU Published Weekly by the StudentS of Wake Forest College I VlQl. XX, No. 24 .. W.AKE FOREST, N. C., SATURDAY, .APRIL 17, 1937 Ten Cents Per Copy LOCAL CLUBS TO PARTICIPATE IN. ANTI-WAR STRIKE ----~--------------* Patterson Releases List of 128 Wake Forest Head Honored By ;-----------: Literary, Religious, and Musi Men Averaging About Jefferson Medical College Elected cal Organizations to Take 90 Per Cent This Week Part in Demonstration TWO FRESHMEN AND ONE KITCHIN HAS SERVED CLASSES TO BE CUT SHORT SOPH MAKE STRAIGHT "A" AS COUNCIL OFFICER TO PROVIDE FOR MEETING Copple, Gilmore, Stanfield and Dean R. V. Patterson of Phila· Martin and Shore to Speak; Modlin Hit Bull's Eye For delphia Institution Sends Con· Prize Offered for Best Plac Top Grades ui All Subjects; gratulations; Great Progress ard; Opposition to Plan Noted . ~eniors Lead List With 36 Seen in Wake .Forest During in Some Quarters; High School Sebolars,· Frosh Come Next Administration of President Students Will Join College With 33, Juniors 31, Sopbs Kitchin; $700,000 Building Men in Demonstration; Judg· 22; Law and Med Schools . Program Completed During ing of Frat Banners Will Be Place Three Each. Last Seven Years. Held at 10 O'clock Thuisday The Wake Forest college mid-se- Dr. Thurman D. Kithin this week Cooperating with l,OOO,OOO other mester honor roll, released by Reg- was made president of the General college students, throughout the na- istrar Grady S. Paterson this week, Alumni Association of Jefferson tion, the Statesman's club, literary listed 128 men, of whom four made Medical College, according to a dis· societLes,· . -

Kit Young's Sale #100

KIT YOUNG’S SALE #100 1954 WILSON FRANKS – RARE Issued with hot dogs, these cards are nearly impossible to find in nice grade. On top of that, they are difficult to find in general. One of the toughest issues of the 1950’s – we were fortunate to find a set. We’ve broken it up to offer you the opportunity to add them to your collections. Cards all free of typical staining. Only one of each available. Roy Campanella Del Ennis Carl Erskine Ferris Fain Bob Feller Dodgers Phillies Dodgers White Sox Indians GD-VG (light paper loss back) VG-EX VG EX+/EX-MT oc VG $320.00 $200.00 $195.00 $220.00 $295.00 Also available: PR $29.00 Nellie Fox Johnny Groth Stan Hack Gil Hodges Ray Jablonski White Sox White Sox Cubs Dodgers Cardinals GD (ink back) VG-EX GD-VG VG GD-VG/VG $150.00 $235.00 $110.00 $350.00 $75.00 Harvey Kuenn Roy McMillan Andy Pafko Paul Richards Hank Sauer Tigers Reds Braves White Sox Cubs GD (pencil erasure) GD-VG/VG GD-VG EX+ o/c GD-VG $48.00 $75.00 $79.00 $195.00 $139.00 Red Schoendienst Enos Slaughter Vern Stephens Sammy White Ted Williams Cardinals Yankees Orioles Red Sox Red Sox GD-VG FR-GD FR-GD EX-MT o/c Please Call $159.00 $79.95 $48.00 $235.00 Also available: GD $55.00 KIT YOUNG CARDS • 4876 SANTA MONICA AVE, #137 • DEPT. S-100 • SAN DIEGO, CA 92107 • (888) 548-9686 • KITYOUNG.COM 1964 TOPPS STAND UPS We recently broke up a complete set of this popular issue – all singles available.