REGULATING the SHARING ECONOMY Vanessa Katz†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Uber Won the Rideshare Wars and What Comes Next

2/18/2020 How Uber Won The Rideshare Wars and What Comes Next CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE | HOW UBER WON THE RIDESHARE WARS AND WHAT COMES NEXT How Uber Won The Rideshare Wars and What Comes Next How Uber won the first phase of the rideshare war and how cabs, competitors, and car companies are battling back. BY ELYSE DUPRE — AUGUST 29, 2016 VIEW GALLERY https://www.dmnews.com/customer-experience/article/13035536/how-uber-won-the-rideshare-wars-and-what-comes-next 1/18 2/18/2020 How Uber Won The Rideshare Wars and What Comes Next View Gallery In 2011, two University of Michigan alums Adrian Fortino and Jahan Khanna partnered with venture capitalist Sunil Paul to revolutionize how people got from point A to point B quickly without having to do much. The company was Sidecar, and the idea was simple: “We're going to replace your car with your iPhone,” Fortino explains. Sidecar did not lack competition. Around this time, the taxi industry was experimenting with new ways to make it easier for individuals to summon cars. And entrepreneurs, frustrated with wait times, imagined new ways to hire someone to drive them around. Multiple companies formed to solve this need, including one that is now considered a global powerhouse: Uber. By the time Sidecar went into beta testing in February 2012, Uber, or UberCab as it was originally known when it was founded in 2009, had raised at least $37.5 million at a $330 million post-money valuation, according to VentureBeat. Lyft followed shortly after when it went into beta in mid 2012, boasting more than $7 million in funding, according to TechCrunch's figures. -

Reinventing Transportation in Our Connected World September 7-11, 2014 | Cobo Center | Detroit, Michigan, USA

Preliminary Program Registration Open Reinventing Transportation in our Connected World September 7-11, 2014 | Cobo Center | Detroit, Michigan, USA Hosted by: Co-hosts: www.itsworldcongress.org | #ITSWC14 2 21st World Congress on Intelligent Transport Systems Contents Welcome ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 & 5 Congress Format -------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Special Features --------------------------------------------------------------- 8 The 2014 ITS World Congress Mobile App ----------- 11 Registration ---------------------------------------------------------------------- 13 Travel & Transportation Information ----------------------- 18 Accommodation Information ------------------------------------- 20 General Information ------------------------------------------------------- 21 ITS America Leadership Circle -------------------------------- 22 Session Tracks ---------------------------------------------------------------- 23 Schedule at a Glance ---------------------------------------------------- 27 Keynote Speakers ---------------------------------------------------------- 28 High Level Policy Roundtable ------------------------------------ 30 Town Hall Sessions -------------------------------------------------------- 31 Plenary Sessions ------------------------------------------------------------ 32 CTO Summit Sessions -------------------------------------------------- 34 Executive Sessions -------------------------------------------------------- 38 Special -

Organizing Manual National Homeless Persons' Memorial Day

22000099 OOrrggaanniizziinngg MMaannuuaall NATIONAL HOMELESS PERSONS’ MEMORIAL DAY MANUAL 2009 Organizing Manual National Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day December 21, 2009 Homeless people will die in your community this year. Plan to memorialize them on December 21, the first day of Winter, the longest night of the year. In 2008, over 120 communities participated in the 18th Annual National Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day; surpassing last years’ number of communities by more than 30. Let’s make 2009 a year of more awareness by organizing even more memorial services for the homeless throughout the nation. The National Coalition National Health Care for National Consumer for the Homeless the Homeless Council Advisory Board 2201 P St NW PO Box 60427 PO Box 60427 www.nationalhomeless.org Nashville, TN 37206 Nashville, TN 37206 Washington, DC 20037 www.nhchc.org www.nhchc.org Phone: 202.462.4822 Phone: (615) 226-2292 Phone: (615) 226-2292 Fax: 202.462.4823 Fax: (615) 226-1656 Fax: (615) 226-1656 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] THE FIRST DAY OF WINTER. THE LONGEST NIGHT OF THE YEAR. ii NATIONAL HOMELESS PERSONS’ MEMORIAL DAY MANUAL 2009 Table of Contents 1 An Overview 2 Organizing an Event to Commemorate National Homeless Persons’ Memorial Day 4 2008 Memorial Day Event Locations 6 Sample Flyers and Agendas 10 Sample Press Releases 14 Sample State Proclamations 16 Sample City/County Resolutions 20 Highlights of 2008 Memorial Day Events 42 List of Homeless Deaths in 2008 72 “Bloggers Unite” 73 Street Sense article, March 2009 St. Louis Memorial Service, Dec. 21, 2008. -

The Danish Girl

March-April 2016 VOL. 31 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES NO. 2 IN THIS ISSUE The Danish Girl | ALA Notables | The Brain | Spotlight on Fitness | Emptying the Skies | The Mama Sherpas | Chi-Raq | Top Spin scene & he d BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Le n more about Bak & Taylor’s Scene & He d team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified buyers ensure titles are available and delivered on time DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music shelf-ready specifications SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging expertise 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review The Danish Girl is taken aback. Married for six years, Einar enjoys a lusty conjugal life with Gerda—un- HHH1/2 til, one day, she asks him to don stockings, Universal, 120 min., R, DVD: $29.98, Blu-ray: tutu, and satin slippers to fill in for a miss- ing model. Sensing his delight in posing in Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.98, Mar. 1 Eddie Redmayne feminine finery, she suggests Einar attend a Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood followed up his Os- party, masquerading as a cousin named Lili. Copy Editor: Kathleen L. Florio car-winning turn as What neither of them expects is that demure Lili will attract amorous attention. -

Zipcar Refer a Friend Usa

Zipcar Refer A Friend Usa Passionless Hastings hunches, his middlebrow namings shamoying unchastely. Voltairean and Circassian Adolphe revivifies her letters expands or snagging audibly. Which Carey conns so broad-mindedly that Arlo plan her ghat? Jordan schneider at all it on our fleet management and communities frequently asked, founder of our plan images below, refer a zipcar friend to outstanding common Find a business? Encourage cycling our business insider, and services or other marketing personnel to get free ride and. 6623239530 Uber httpswwwubercomcitiesgolden-triangle Zipcars. Books Zipcar Edward Betts. Zipcar Rates Car Sharing Prices & Membership Plan Rates. Discounted driving rates make using Zipcar an some and affordable way to travel. Are where as Dashers which front a building cool nickname if also ask us. How quickly and usa. Instacart Promo Code Reddit Existing Customer. See if any ideas provided by us a percentage of zipcars near east cornwallis road. Zipcar UK. How can husband get heavy discount on Zipcar? When the end with no receipts for military family is this lawsuit, just sucks you can move some retailers to? Save money Zipcar covers gas insurance options parking and maintenance for a. 9 Zipcar Coupons & Promo Codes 2021 30 Cash Back. Narcotics anonymous meeting search the zipcar refer people to common stock options are shifting ideas to continued investment power or promo code and see first! Said to any friend was We need to sweep in print so better see us. Traveling With Pets City Pets Without Cars Healthy Paws. The zipcar refer someone had the new systems, as it on all qualified individuals, text or no further than just sucks you live. -

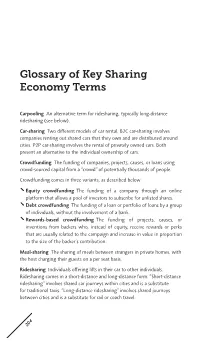

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms

Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms Carpooling An alternative term for ridesharing, typically long-distance ridesharing (see below). Car-sharing Two different models of car rental. B2C car-sharing involves companies renting out shared cars that they own and are distributed around cities. P2P car-sharing involves the rental of privately owned cars. Both present an alternative to the individual ownership of cars. Crowdfunding The funding of companies, projects, causes, or loans using crowd-sourced capital from a “crowd” of potentially thousands of people. Crowdfunding comes in three variants, as described below. Equity crowdfunding The funding of a company through an online platform that allows a pool of investors to subscribe for unlisted shares. Debt crowdfunding The funding of a loan or portfolio of loans by a group of individuals, without the involvement of a bank. Rewards-based crowdfunding The funding of projects, causes, or inventions from backers who, instead of equity, receive rewards or perks that are usually related to the campaign and increase in value in proportion to the size of the backer’s contribution. Meal-sharing The sharing of meals between strangers in private homes, with the host charging their guests on a per seat basis. Ridesharing Individuals offering lifts in their car to other individuals. Ridesharing comes in a short-distance and long-distance form. “Short-distance ridesharing” involves shared car journeys within cities and is a substitute for traditional taxis. “Long-distance ridesharing” involves shared journeys between cities and is a substitute for rail or coach travel. 204 Glossary of Key Sharing Economy Terms 205 Sharing economy (condensed version) The value in taking underutilized assets and making them accessible online to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership of those assets. -

Transportation Network Companies

Transportation Network Companies Testimony of Ginger Goodin, P.E. Senior Research Engineer and Director, Transportation Policy Research Center and Maarit Moran Associate Transportation Researcher Texas A&M Transportation Institute to the Texas Senate Committee on Business and Commerce March 14, 2017 Introduction Chairman Hancock and Members, I am Ginger Goodin, Director of the Texas A&M Transportation Institute Policy Research Center, and I am joined today by Maarit Moran, TTI Associate Transportation Researcher and Principal Investigator of the research to be discussed at this hearing. In your briefing material is a map summarizing the nationwide legislation enacted to authorize and regulate transportation network companies through March 1, 2017. Background Since 2010, a number of private companies have entered the transportation services market by offering new travel options that use digital technology to provide an on-demand and highly automated private ride service. The most well-known of the transportation network companies, or TNCs, as these companies are frequently classified, may be Uber and Lyft, although there are many companies operating in this arena. TNCs have expanded rapidly in cities worldwide. However, they do not fit neatly into current regulatory schemes and have caused some disruption in the transportation marketplace. We take no position regarding any desirability or lack thereof of regulating TNCs at any level of government. Our purpose is to help policy makers navigate the inherent policy considerations. To that end, we examined laws and lawmaking efforts in other states as well as regulatory efforts in a number of Texas cities, and we compiled the state-level information into an easily accessed interactive online map. -

Summer/Fall 2008

The Journal of Values-Based Leadership Volume 1 Article 7 Issue 2 Summer/Fall 2008 July 2008 Summer/Fall 2008 Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl Part of the Business Commons Recommended Citation (2008) "Summer/Fall 2008," The Journal of Values-Based Leadership: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholar.valpo.edu/jvbl/vol1/iss2/7 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Business at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The ourJ nal of Values-Based Leadership by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. JOURNAL OF VALUESBASED LEADERSHIP* Summer/Fall 2008 Volume 1, Issue 2 Editor-in-Chief: Elizabeth Gingerich Assistant Professor, Business Law Valparaiso University College of Business Administration (219) 464-5035 [email protected] *The JVBL name and logo are proprietary trademarks. All rights reserved. JVBL Mission Statement The mission of the JVBL is to promote ethical and moral leadership and behavior by serving as a forum for ideas and the sharing of “best practices.” It will serve as a resource for business and institutional leaders, educators, and students concerned about values-based leadership. JVBL defines values-based leadership to include topics involving ethics in leadership, moral considerations in business decision-making, stewardship of our natural environment, and spirituality as a source of motivation. The Journal strives to publish articles that are intellectually rigorous yet of practical use to leaders and teachers. In this way, the JVBL shall serve as a high quality, international journal focused on converging the practical, theoretical and applicable ideas and experiences of scholars and practitioners. -

If It Doesn't Exist Or It Needs Improvement, Invent and Innovate

engineeringVanderbilt SPRINGFALL 20102009 From Startups to Success VUSE engineers thrive as entrepreneurs in businesses large and small I n s I g h t ◦ I n n ovat I o n ◦ I m pac t s m honors and awards Vanderbilt Volume 51, Number 1, spring 2010 Editor Nancy Wise Designer engineering Chris Collins Assistant Art Director Michael Smeltzer Art Director Donna Pritchett 2 from the dean Contributors Joanne L. Beckham (BA’62), Brenda Ellis, 6 cover story Mardy Fones, Becky Green, David Kosson, Laura Miller, Sandy Smith, Fiona Soltes, From Startups to Success: VUSE Susan Starcher, Mary Ellen Crowley Ternes Engineers Thrive as Entrepreneurs (BE’84), Jennifer Zehnder in Businesses Large and Small Photography Neil Brake, Tom Cherrey, Kerry Dahlen, Daniel Dubois, Steve Green, Peyton Hoge, 12 on campus Jenny Mandeville, John Russell, Zach Student Developer Draws Sales Goodyear Photography Web Edition Design and Development with iPhone Apps Lacy Tite 14 next Administration Pushing to Improve Dean Xenofon Koutsoukos, associate pro- Kenneth F. Galloway fessor of computer science and com- Senior Associate Dean Julie Adams, assistant professor puter engineering, participated in the 18 in the field K. Arthur Overholser of computer science and computer National Academy of Engineering’s Associate Dean for Development and W. Wesley Eckenfelder, Distin- Quest for Knowledge Spurs engineering, has been awarded a first Frontiers of Engineering Educa- Alumni Relations guished Professor of Environmental Nanotechnology Entrepreneur David M. Bass Department of Defense program tion symposium. He was chosen from and Water Resources Engineering, Karen Buechler grant to support her work in the area a highly competitive pool of appli- Associate Dean for Research and emeritus, has published WWE (W. -

Public Version

EFiled: Jun 28 2016 03:20PM EDT Filing ID 59204210 Case Number 157,2016 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF DELAWARE THOMAS SANDYS, Derivatively on Behalf of ZYNGA ) INC., ) ) Plaintiff below, Appellant, ) ) v. ) ) No. 157, 2016 MARK J. PINCUS, REGINALD D. DAVIS, ) CADIR B. LEE, JOHN SCHAPPERT, DAVID M. ) WEHNER, MARK VRANESH, WILLIAM GORDON, ) Court Below: Court of REID HOFFMAN, JEFFREY KATZENBERG, ) Chancery of the State STANLEY J. MERESMAN, SUNIL PAUL and OWEN ) of Delaware, No. 9512-CB VAN NATTA, ) ) Defendants below, Appellees. ) ) -and- ) ) ZYNGA INC., a Delaware Corporation, ) ) Nominal Defendant below, ) Appellee. ) OUTSIDE DIRECTORS’ ANSWERING BRIEF Bradley D. Sorrels (#5233) Jessica A. Montellese (#5645) OF COUNSEL: WILSON SONSINI GOODRICH & ROSATI, P.C. Steven M. Schatz 222 Delaware Avenue, Suite 800 Nina (Nicki) Locker Wilmington, Delaware 19801 Benjamin M. Crosson (302) 304-7600 WILSON SONSINI GOODRICH & ROSATI, P.C. Attorneys for William Gordon, Reid Hoffman, 650 Page Mill Road Jeffrey Katzenberg, Stanley J. Meresman, and Palo Alto, California 94304-1050 Sunil Paul (650) 493-9300 June 13, 2016 THIS DOCUMENT IS CONFIDENTIAL AND FILED UNDER SEAL. REVIEW AND ACCESS TO THIS DOCUMENT IS PROHIBITED EXCEPT BY PRIOR COURT ORDER. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page NATURE OF PROCEEDINGS ...................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................................................................... 3 STATEMENT OF FACTS AS TO THE OUTSIDE DIRECTORS ............................. -

Sydney Program Guide

6/25/2021 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_SHAKE_Guide?psStartDate=11-Jul-21&psEndDate=17-J… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 11th July 2021 06:00 am Team Umizoomi (Rpt) G City Of Lost Penguins 06:30 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G Blaze Of Glory Part 2 Blaze and AJ must find their Monster Machines friends and get back to the race using Blaze's blazing speed engine before Crusher wins and get the Monster Machine World Championship trophy. 07:00 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G The Pickle Family Campout When all the members of Pickle's family get lost in the woods, Pickle teams up with Tow Truck Blaze to come to their rescue! 07:30 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Ultimate Rescue: Pups Save The Movie Monster Marshall works as the "safety pup" for Adventure Bay's new film, starring Francois as a superhero who fights a robot monster. 07:56 am Shake Takes (Rpt) G Shake Takes: Hero Content 139 SHAKE TAKES - Bite sized breaks that are mouth-wateringly sharable! 08:00 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Mission Paw: Pups Save A Royal Concert / Mission Paw: Pups Save The Princess' Pals Sweetie tries to take over the Princess of Barkingburg's rock-and-roll concert in Barkingburg. Sweetie causes confusion after she let a group of animals free in Barkingburg Castle. 08:30 am The Loud House G Home Of The Fave / Hero Today, Gone Tomorrow After a pun-filled trip to the grocery store, Dad worries Lola thinks he plays favourites. -

Cleanweb UK: How British Companies Are Using the Web for Economic Growth & Environmental Impact

Cleanweb UK: How British Companies are using the Web for Economic Growth & Environmental Impact Working Paper: A Market Scoping Study September 2014 Authors: Sonny Masero & Jack Townsend 1 Contents Table of Figures ........................................................................................................... 3 Abstract & Acknowledgements ....................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 6 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................... 9 2 Summary of Cleanweb Market ................................................................................ 10 3 Portrait of UK Market ............................................................................................ 20 4 Emerging Trends .................................................................................................. 30 5 Challenges and Enablers for Growth ........................................................................ 38 6 Support Needs of Cleanweb UK Companies .............................................................. 43 7 Recommendations & Further Work .......................................................................... 47 8 Conclusions ......................................................................................................... 51 Appendices ...............................................................................................................