What Heritage-Based Collaboration Offers the Cross-Border Niagara Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

When the Mountain Became the Escarpment.FH11

Looking back... with Alun Hughes WHEN THE MOUNTAIN BECAME THE ESCARPMENT The Niagara Escarpment hasnt always been But Coronelli was not the first to put Niagara known by that name. Early in the 19th century it on the map. That distinction belongs to Father Louis was often referred to as the Mountain, and of course Hennepin, the Recollect priest who was the first it is still called that in Hamilton and Grimsby today. European to describe Niagara Falls from personal We in eastern Niagara have largely forgotten the observation. In his Description de la Louisiane, name, though it survives in the City of Thorolds published in 1683, five years after his visit, he speaks motto Where the Ships Climb the Mountain. of le grand Sault de Niagara, and labels it thus on the accompanying map. This is the form that So when did the name Niagara Escarpment first prevails thereafter, and it is the spelling used for Fort come into use? And what about the areas other de Niagara, established by the French at the mouth Niagara names, like Niagara Falls, Niagara River of the river in 1726. The English followed suit, and Niagara Peninsula? When did these first appear? though on many early maps (e.g. Moll 1715, I dont pretend to have definitive answers there Mitchell 1782) they use the name Great Fall of are too many sources I have not seen but I can Niagara rather than Niagara Falls. suggest some preliminary conclusions. In his Description Hennepin also refers to la The name Niagara is definitely of native origin, belle Riviere de Niagara, so the name Niagara though there is no agreement about its meaning. -

Of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara

of the American Falls at Niagara 1I I Preservation and Enhancement of the American Falls at Niagara Property of t';e Internztio~al J5it-t; Cr?rn:n es-un DO NOT' RECda'dg Appendix G - Environmental Considerations Final Report to the International Joint Commission by the American Falls International Board June -1974 PRESERVATION AND ENHANCEMENT OF AMERICAN FALLS APPENDIX. G .ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER G 1 .INTRODUCTION G1 CHAPTER G2 .ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING . NIAGARA RESERVATION AND SURROUNDING REGION GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................... PHYSICAL ELEMENTS ..................................................................... GENERAL .................................................................................... STRATIGRAPHY ......................................................................... SOILS ............................................................................................ WATER QUALITY ........................................................................ CLIMATE INVENTORY ................................................................... CLIMATE ....................................................................................... AIR QUALITY .............................................................................. BIOLOGICAL ELEMENTS ................................................................ TERRESTRIAL VEGETATION ..................................................... TERRESTRIAL WILDLIFE ......................................................... -

It's Happeninghere

HAMILTON IT’S HAPPENING HERE Hamilton’s own Arkells perform at the 2014 James Street Supercrawl – photo credit: Colette Schotsman www.tourismhamilton.com HAMILTON: A SNAPSHOT Rich in culture and history and surrounded by spectacular nature, Hamilton is a city like no other. Unique for its ideal blend of urban and natural offerings, this post-industrial, ambitious city is in the midst of a fascinating transformation and brimming with story ideas. Ideally located in the heart of southern Ontario, midway between Toronto and Niagara Falls, Hamilton provides an ideal destination or detour. From its vibrant arts scene, to its rich heritage and history, to its incredible natural beauty, it’s happening here. Where Where Where THE ARTS NATURE HISTORY thrive surrounds is revealed Hamilton continues to make Bounded by the picturesque shores One of the oldest and most headlines for its explosive arts scene of Lake Ontario and the lush historically fascinating cities in the – including a unique grassroots landscape of the Niagara region outside of Toronto, Hamilton movement evolving alongside the Escarpment, Hamilton offers a is home to heritage-rich architecture, city’s long-established arts natural playground for outdoor lovers world-class museums and 15 institutions. Inspiring, fun and – all within minutes of the city’s core. National Historic Sites. accessible, the arts in Hamilton are yours to explore. • More than 100 waterfalls can be • Dundurn Castle brings Hamilton’s found just off the Bruce Trail along Victorian era to life in a beautifully • Monthly James Street North the Niagara Escarpment, a restored property overlooking the Art Crawls and the annual James UNESCO World Biosphere Reserve harbour while Hamilton Museum of Street Supercrawl draw hundreds of that cuts across the city. -

Summer Reading Program

OUR MISSION SUMMER READING PROGRAM Recent Improvements To strengthen our community through lifelong learning with access to varied collections, • Archives catalog online for Summer Reading Program 2019 programs, and assistance with digital literacy. researchers to browse, Jan. 2019 Each year the Niagara Falls Public Library participates in New York State Summer (https://nflh.libraryhost.com/ ) Reading Program. For 2019, the theme was A Universe of Stories and the Niagara Falls he theme of NFPL services is a vision to build a stronger • In partnership with the Niagara Falls Heritage Area, Public Library had 130 children participate in our “Read and Bead” challenge. Upon community. We are looking forward, planning the directive registering, participants received a chain; time spent reading earned whimsically shaped beads to add to the chain. Tof library services. comprehensive, multi phase inventory of Local History In a January 2020 nationwide Gallup poll, Americans visited their In addition, through generous support from the Friends of the Library and Nioga Library System, we hosted a collection, Phase 1 - May local libraries more frequently than attending the movie theater. On 2019, Phase 2 began in June 2020 family entertainment series that included Dave and Kathleen Jeffers “Make Space for Reading” Show, Checkers average, U.S. adults took 10.5 trips to a local library in 2019, twice the Inventor’s “Back to the Moon Show” and a weekly family film series on Friday afternoons. We offered weekly as many times as going to a movie, theatrical event, or visiting a • Continued Digitization of local history items national/historic park. With this increase in usage, coupled with a through RBD grants and Senator Ortt Bullet Aid story hours for preschoolers and summer fun clubs with space-related STEAM themes for grade school children; need for electronic services, the NFPL is looking towards the future, monies. -

Source Index

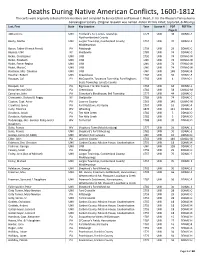

Deaths During Native American Conflicts, 1600-1812 The cards were originally collected from members and compiled by Eunice Elliott and Samuel C. Reed, Jr. for the Western Pennsylvania Genealogical Society. (Original research was named Indian Victims Killed, Captured, & Missing) Last, First State Key Location Year Source # PDF PDF File Page # 108 settlers UNK Freeland’s Fort, Lewis Township, 1779 UNK 48 DDNAC-F Northumberland County Barcly, Matha UNK Lurgan Township, Cumberland County; 1757 UNK 70 DDNAC-F Middlesprings Baron, Father (French Priest) PA Pittsburgh 1759 UNK 29 DDNAC-G Bayless, UNK KY Shelbyville 1789 UNK 74 DDNAC-C Bickel, Christopher UNK UNK 1792 UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Elizabeth UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Esther Regina UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Bickel, Maria C UNK UNK UNK UNK 74 DDNAC-W Boatman, Mrs. Claudina UNK UNK UNK UNK 148 DDNAC-B Boucher, Robert UNK Greensburg 1782 UNK 56 DDNAC-F Bouquet, Col. PA McCoysville, Tuscarora Township; Fort Bingham; 1756 UNK 4 DDNAC-I Beale Township, Juniata County Bouquet, Col. PA Big Cove, Franklin County 1763 UNK 64 DDNAC-L Brownlee and Child PA Greensburg 1782 UNK 58 DDNAC-M Carnahan, John PA Carnahan’s Blockhouse, Bell Township 1777 UNK 44 DDNAC-C Chenoweth, Richard & Peggy KY Shelbyville 1789 UNK 74 DDNAC-C Clayton, Capt. Asher PA Luzerne County 1763 UNK 140 DDNAC-W Crawford, James PA Fort Redstone; Kentucky 1767 UNK 16 DDNAC-R Curly, Florence WV Wheeling 1876 UNK 141 DDNAC-S Davidson, Josiah PA Ten Mile Creek 1782 UNK 5 DDNAC-D Davidson, Nathaniel PA Ten Mile Creek 1782 UNK 5 DDNAC-D Dodderidge, Mrs. -

Rethinking the Niagara Frontier

Ongoing work in the Niagara Region Next Steps Heritage Development in Western New York The November Roundtable concluded with a lively Rethinking the Niagara Frontier It would be a mistake, however, to say that the process of heritage development has discussion of the prospects for bi-national cooperation European Participants yet to begin here. around issues of natural and cultural tourism and her- itage development. There is no shortage of assets or Michael Schwarze-Rodrian As Bradshaw Hovey of UB’s smaller scale and at a finer grain. Projekt Ruhr GmbH Urban Design Project outlined, He highlighted the case of Fort stories, and there is great opportunity we can seize by Berliner Platz 6-8 A report on the November Roundtable there are initiatives in environ- Erie, one of the smaller commu- working together. Essen, Germany 45127 mental repair, historic preserva- nities in the region, but one that Email: schwarze-rodrian@projek- tion, infrastructure investment, rightfully lays claim to the title of Some identified the need to truhr.de economic development, and cul- “gateway to Canada.” broaden and deepen grassroots November 20, 2000 tural interpretation ongoing from What Fort Erie has done is rel- involvement, while others zeroed Christian Schützinger one end of the region to the atively simple. They have in on the necessity of engaging Bodensee-Alpenrhein Tourismus other. matched local assets with eco- leadership at higher levels of gov- Focus on heritage Bethlehem Steel Plant Postfach 16 In Buffalo, work is proceeding Source: Patricia Layman Bazelon nomic trends and community ernment and business. There was A-6901 Bregenz, Austria To develop the great bi-national region that spans the Niagara River, we should on the redevelopment of South goals to identify discrete areas of a great deal of discussion about Email: c.schuetzinger@bodensee- Buffalo “brownfields”; aggressive works; and a cultural tourism desired investment. -

Underground Railroad in Western New York

Underground Railroad on The Niagara Frontier: Selected Sources in the Grosvenor Room Key Grosvenor Room Buffalo and Erie County Public Library 1 Lafayette Square * = Oversized book Buffalo, New York 14203-1887 Buffalo = Buffalo Collection (716) 858-8900 Stacks = Closed Stacks, ask for retrieval www.buffalolib.org GRO = Grosvenor Collection Revised June 2020 MEDIA = Media Room Non-Fiction = General Collection Ref. = Reference book, cannot be borrowed 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 Books .............................................................................................................................. 2 Newspaper Articles ........................................................................................................ 4 Journal & Magazine Articles .......................................................................................... 5 Slavery Collection in the Rare Book Room ................................................................... 6 Vertical File ..................................................................................................................... 6 Videos ............................................................................................................................. 6 Websites ......................................................................................................................... 7 Further resources at BECPL ......................................................................................... -

3.1 Physical Environment 3.2 Natural Environment

CLASS ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT REPORT City of Hamilton HAMILTON TRANSPORTATION MASTER PLAN 3. DESCRIPTION OF EXISTING ENVIRONMENT This section provides a broad description of City’s existing physical, natural, socio-economic, cultural and recreational resources based on information derived from the City of Hamilton, the Ministry of Natural Resources, various Conservation Authorities, the Niagara Escarpment Commission and the Hamilton Naturalists Club. Exhibit 3.1 provides an overall geographic context for the discussion. 3.1 Physical Environment The City of Hamilton spans an area that covers 1171 km2 and is located at the apex of Ontario’s Golden Horseshoe. The landscape includes parts of six distinct physiographic regions (Niagara Escarpment, Iroquois Plain, Flamborough Plain, Horseshoe Moraines, Norfolk Sand Plain and Haldimand Clay Plain), and can primarily be described in terms of three prominent landform features: • The Niagara Escarpment, which runs parallel to the shoreline and is set back approximately 2 km inland; • The western Lake Ontario shoreline, including the Hamilton Harbour embankment; and • The Dundas Valley, partially buried bedrock gorge that shapes a major indentation in both the shoreline and Escarpment. The Niagara Escarpment, formed by differential erosion, is a 725 km long ridge that runs from the tip of the Bruce Peninsula, through Hamilton to Niagara Falls along the southern edge of Lake Ontario. Physiographic regions located above the Escarpment, in the communities of Flamborough, Ancaster and Glanbrook are comprised primarily of bedrock, sand and clay plains. The Galt moraine, a major glacial ridge, is also located above the Escarpment skirting the northwestern boundary of the City. This northern area of Hamilton also contains a number of scattered drumlin fields, moraines and other landforms directly descendant from glacial processes. -

Military Occurrences

A. FULL AND CORRECT ACCOUNT OF THE MILITARY OCCURRENCES OF LHC THE LATE WAR 973.3 BETWEEN J29 GREAT BRITAIN AND THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA; WITH AN APPENDIX, AND PLATES. BY WILLIAM JAMES, AUTHOR OF " A FULL AND CORRECT ACCOUNT OF THE CHIEF NAVAL OCCURRENCES, &C." .ellterum alterius auxilio eget. SALLUST. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. Unbolt : PRINTED FOR THE AUTHOR: SOLD BY BLACK, KINGSBURY, PARBURY, AND ALLEN, LEADENHALL-STREET; - JAMES M. RICHARDSON, CORNHILL ; JOHN BOOTH, DUKE STREET / PoRTLAN D -PLACE ;. AND ALL OTHER BOOKSELLERS. 1818. .44 '1) 1" 1'.:41. 3 1111 MILITARY OCCURRENCES, .c. 4. CHAPTER XI. British force on the Niagara in October, 1813 — A ttack upon the piquets—Effects of the surrender of the right division—Major-general Vincent's retreat to Burlington— His orders from the commander-in-clarf to retire upon Kingston— Fortunate contravention of those orders—General Harrison's arrival at, and departure from Fort- George Association of some Upper Canada militia after being disembodied—Their gallant attack upon, and capture of, a band of plunder-. ing traitors—General M'Clure's shameful con , duct towards the Canadian inhabitants—Colonel Murray's gallant behaviour Its effect upon general M'Clure—A Canadian winter—Night- conflagration of Newark by the Americians- M'Clure's abandonment of Fort-George, and flight across the river=–Arrival of lieutenant- general DruMmond—Assault upon, and capture of Fort-Niagara — Canadian prisoners found there Retaliatory destruction of LeWistown, VOL. Jr. MILITARY OCCURRENCES BETWEEN GREAT BRITAIN AND AMERICA. 3 Youngstown,Illanchester ,and Tuscarora—Attack consisting of 1100 men, with the great general upon Bufaloe and Black Rock, and destruction Vincent, at their head, fled into the woods." Of those ifillagei—Americaii resentment against The British are declared to have sustained a general 31' Clure—Rernarks upon the campaign ; loss of 32 in killed only, and the Americans of also upon the burning of Newark, and the four killed and wounded. -

Niagara National Historic Sites of Canada Draft Management Plan 2018

Management Plan Niagara 2018 National Historic Sites of Canada 2018 DRAFT Niagara National Historic Sites of Canada Draft Management Plan ii Niagara National Historic Sites iii Draft Management Plan Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .................................................................................... 1 2.0 Significance of Niagara National Historic Sites .............................. 1 3.0 Planning Context ............................................................................ 3 4.0 Vision .............................................................................................. 5 5.0 Key Strategies ................................................................................ 5 6.0 Management Areas ......................................................................... 9 7.0 Summary of Strategic Environmental Assessment ....................... 12 Maps Map 1: Regional Setting ....................................................................... 2 Map 2: Niagara National Historic Sites Administered by Parks Canada in Niagara-on-the-Lake ........................................................... 4 Map 3: Lakeshore Properties and Battlefield of Fort George National Historic Site .......................................................................... 10 iv Niagara National Historic Sites 1 Draft Management Plan 1.0 Introduction Parks Canada manages one of the finest and most extensive systems of protected natural and historic places in the world. The Agency’s mandate is to protect and present these places -

Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority Proposal Cover

Final Report June 2017 Transit Survey for GBRNTC moore & associates 2017 Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority Onboard Survey Greater Buffalo-Niagara Regional Transportation Council Final Report Table of Contents Chapter 1: Executive Summary .................................................... 01 Chapter 2: Overview and Methodology ....................................... 07 Chapter 3: Analysis and Key Findings ........................................... 19 Chapter 4: Spatial Analysis .......................................................... 77 Appendix A: Survey Instrument – Bus Survey .............................. A-1 Appendix B: Survey Instrument – Rail Survey .............................. B-1 Appendix C: Simple Frequencies – Bus Survey ............................. C-1 Appendix D: Simple Frequencies – Rail Survey ............................. D-1 Appendix E: Transfer Matrix ....................................................... E-1 Appendix F: Data Dictionary ........................................................ F-1 Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2017 2017 Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority Onboard Survey Greater Buffalo-Niagara Regional Transportation Council Final Report This page intentionally blank. Moore & Associates, Inc. | 2017 2017 Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority Onboard Survey Greater Buffalo-Niagara Regional Transportation Council Final Report Chapter 1 Executive Summary In 2017, the Greater Buffalo-Niagara Transportation Council retained Moore & Associates to conduct an origin/destination study of -

Imagine Niagara

This page has been intentionally left blank. Chapter 1 1 - 2 1. Imagine Niagara Physical and Economic Background The Regional Municipality of Niagara is located in Southern Ontario between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. It corresponds approximately to the area commonly referred to as the "Niagara Peninsula" and will be referred to here as simply "the Region". It is bounded on the east by the Niagara River and the State of New York, and on the west by the City of Hamilton and Haldimand County. The Region is at one end of the band of urban development around the western end of Lake Ontario. Chapter 1 1 - 3 The Region was formed in 1970 and includes all of the areas within the boundaries of the former Counties of Lincoln and Welland. There are twelve local municipalities within the Region; these were formed by the rearrangement and amalgamation of the twenty-six municipalities which existed before 1970. The Queen Elizabeth Way and other provincial highways place most of the Region within ninety minutes' travel time of Toronto. Hamilton-Wentworth, with a population of over 400,000, is about thirty minutes away from the centre of the Region. Four road and two rail bridges connect the Region to the western part of New York State. About 2,500,000 people live along the United States' side of the Niagara River. The developing industrial complex at Nanticoke, on the shore of Lake Erie to the southwest, is about an hour's travel time from the centre of the Region. Physical Characteristics The "Niagara Peninsula" area is not a true peninsula but is a narrow neck of land stretching between Lakes Erie and Ontario.