Pharmacy Services in Solid Organ Transplantation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

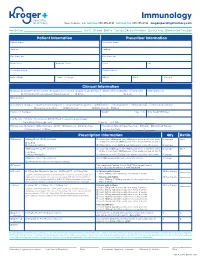

Immunology New Orleans, LA Toll Free 888.355.4191 Toll Free Fax 888.355.4192 Krogerspecialtypharmacy.Com

Immunology New Orleans, LA toll free 888.355.4191 toll free fax 888.355.4192 krogerspecialtypharmacy.com Need By Date: _________________________________________________ Ship To: Patient Office Fax Copy: Rx Card Front/Back Clinical Notes Medical Card Front/Back Patient Information Prescriber Information Patient Name Prescriber Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Main Phone Alternate Phone Phone Fax Social Security # Contact Person Date of Birth Male Female DEA # NPI # License # Clinical Information Diagnosis: J45.40 Moderate Asthma J45.50 Severe Asthma L20.9 Atopic Dermatitis L50.1 Chronic Idiopathic Urticaria (CIU) Eosinophil Levels J33 Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyposis Other: ________________________________ Dx Code: ___________ Drug Allergies Concomitant Therapies: Short-acting Beta Agonist Long-acting Beta Agonist Antihistamines Decongestants Immunotherapy Inhaled Corticosteroid Leukotriene Modifiers Oral Steroids Nasal Steroids Other: _____________________________________________________________ Please List Therapies Weight kg lbs Date Weight Obtained Lab Results: History of positive skin OR RAST test to a perennial aeroallergen Pretreatment Serum lgE Level: ______________________________________ IU per mL Test Date: _________ / ________ / ________ MD Specialty: Allergist Dermatologist ENT Pediatrician Primary Care Prescription Type: Naïve/New Start Restart Continued Therapy Pulmonologist Other: _________________________________________ Last Injection Date: _________ / ________ -

STEM Disciplines

STEM Disciplines In order to be applicable to the many types of institutions that participate in the HERI Faculty Survey, this list is intentionally broad and comprehensive in its definition of STEM disciplines. It includes disciplines in the life sciences, physical sciences, engineering, mathematics, computer science, and the health sciences. Agriculture/Natural Resources Health Professions 0101 Agriculture and related sciences 1501 Alternative/complementary medicine/sys 0102 Natural resources and conservation 1503 Clinical/medical lab science/allied 0103 Agriculture/natural resources/related, other 1504 Dental support services/allied 1505 Dentistry Biological and Biomedical Sciences 1506 Health & medical administrative services 0501 Biochem/biophysics/molecular biology 1507 Allied health and medical assisting services 0502 Botany/plant biology 1508 Allied health diagnostic, intervention, 0503 Genetics treatment professions 0504 Microbiological sciences & immunology 1509 Medicine, including psychiatry 0505 Physiology, pathology & related sciences 1511 Nursing 0506 Zoology/animal biology 1512 Optometry 0507 Biological & biomedical sciences, other 1513 Osteopathic medicine/osteopathy 1514 Pharmacy/pharmaceutical sciences/admin Computer/Info Sciences/Support Tech 1515 Podiatric medicine/podiatry 0801 Computer/info tech administration/mgmt 1516 Public health 0802 Computer programming 1518 Veterinary medicine 0803 Computer science 1519 Health/related clinical services, other 0804 Computer software and media applications 0805 Computer systems -

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series

Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability September 25, 2019 National Council on Disability (NCD) 1331 F Street NW, Suite 850 Washington, DC 20004 Organ Transplant Discrimination Against People with Disabilities: Part of the Bioethics and Disability Series National Council on Disability, September 25, 2019 This report is also available in alternative formats. Please visit the National Council on Disability (NCD) website (www.ncd.gov) or contact NCD to request an alternative format using the following information: [email protected] Email 202-272-2004 Voice 202-272-2022 Fax The views contained in this report do not necessarily represent those of the Administration, as this and all NCD documents are not subject to the A-19 Executive Branch review process. National Council on Disability An independent federal agency making recommendations to the President and Congress to enhance the quality of life for all Americans with disabilities and their families. Letter of Transmittal September 25, 2019 The President The White House Washington, DC 20500 Dear Mr. President, On behalf of the National Council on Disability (NCD), I am pleased to submit Organ Transplants and Discrimination Against People with Disabilities, part of a five-report series on the intersection of disability and bioethics. This report, and the others in the series, focuses on how the historical and continued devaluation of the lives of people with disabilities by the medical community, legislators, researchers, and even health economists, perpetuates unequal access to medical care, including life- saving care. Organ transplants save lives. But for far too long, people with disabilities have been denied organ transplants as a result of unfounded assumptions about their quality of life and misconceptions about their ability to comply with post-operative care. -

Pharmacy/Medical Drug Prior Authorization Form

High Cost Medical Drugs List High Cost Medical Drugs administered by Health Alliance™ providers within physician offices, infusion centers or hospital outpatient settings must be acquired from preferred specialty vendors. Health Alliance will not reimburse any drug listed as a “High Cost Medical Drug,” whether obtained from the provider’s own stock or via “buy-and-bill.” This drug list does not apply to members with Medicare coverage. Information on how to acquire these medications is located at the end of this document. Recent Updates Preferred Contact Drug Therapy Drug Name Code PA Effective Change Vendor Number Oncology – Injectable DARZALEX FASPRO J9144 YES 10/1/2021 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Added High Cost Medical Drug List Preferred Contact Drug Therapy Drug Name Code PA Effective Vendor Number Acromegaly SANDOSTATIN J2353 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Acromegaly SOMATULINE J1930 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products JETREA J7316 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products PROLASTIN J0256 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products QUTENZA J7336 NO 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products REVCOVI J3590 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products RADICAVA J1301 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products SIGNIFOR J2502 YES 7/1/2020 Accredo® 866-759-1557 Additional Products SPRAVATO J3490 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Additional Products STRENSIQ J3590 YES 7/1/2020 LDD Additional Products THIOTEPA J9340 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 Allergic Asthma CINQAIR J2786 YES 7/1/2020 CVS/Caremark® 800-237-2767 -

The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J

Hastings Law Journal Volume 21 | Issue 1 Article 4 1-1969 The tS ory of Organ Transplantation J. Englebert Dunphy Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation J. Englebert Dunphy, The Story of Organ Transplantation, 21 Hastings L.J. 67 (1969). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. The Story of Organ Transplantation By J. ENGLEBERT DUNmHY, M.D.* THE successful transplantation of a heart from one human being to another, by Dr. Christian Barnard of South Africa, hias occasioned an intense renewal of public interest in organ transplantation. The back- ground of transplantation, and its present status, with a note on certain ethical aspects are reviewed here with the interest of the lay reader in mind. History of Transplants Transplantation of tissues was performed over 5000 years ago. Both the Egyptians and Hindus transplanted skin to replace noses destroyed by syphilis. Between 53 B.C. and 210 A.D., both Celsus and Galen carried out successful transplantation of tissues from one part of the body to another. While reports of transplantation of tissues from one person to another were also recorded, accurate documentation of success was not established. John Hunter, the father of scientific surgery, practiced transplan- tation experimentally and clinically in the 1760's. Hunter, assisted by a dentist, transplanted teeth for distinguished ladies, usually taking them from their unfortunate maidservants. -

Current Status of Immunology Education in US Schools And

American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 2019; 83 (7) Article 6994. RESEARCH Current Status of Immunology Education in US Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy Yuan Zhao, PhD,a Dana Ho, PharmD,a Benjamin Oldham, PharmD,a Bonnie Dong, PharmD,a Daniel Malcom, PharmDa,b a Sullivan University College of Pharmacy, Louisville, Kentucky b Associate Editor, American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, Arlington, Virginia Submitted February 2, 2018; accepted June 17, 2018; published September 2019. Objective. To determine the extent of immunology education in US Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) programs. Methods. Curricular information on immunology education was collected from the web pages of US PharmD programs (N5142). The data were sorted, comparisons were made, and trends were identified. Results. Of 142 PharmD programs studied, 100% posted curriculum information on their websites. Among them, 73 programs (51.4%) had a dedicated immunology course in their curriculum, either as an independent course or a course combined with another subject. Most immunology education was offered in the first professional year (72.5%). Of the programs that offered immunology as an in- dependent course, the number of semester hours dedicated to the course varied from 1.5 to 3.5 (median53, mode53, mean52.7). More three-year programs offered immunology as a core compo- nent in the didactic curriculum than did four-year programs (64.7% vs 49.6%). Similarly, more private programs offered immunology than did public programs (64% vs 37.3%). Conclusion. Immunology education in US schools and colleges of pharmacy lacks consensus. Not all PharmD programs indicated they offered specific, focused immunology education in their curricula. -

Telepharmacy Rules and Statutes: a 50-State Survey

American Journal of Medical Research 5(2), 2018 pp. 7–23, ISSN 2334-4814, eISSN 2376-4481 doi:10.22381/AJMR5220181 TELEPHARMACY RULES AND STATUTES: A 50-STATE SURVEY GEORGE TZANETAKOS Department of Health Management and Policy, College of Public Health, The University of Iowa FRED ULLRICH Department of Health Management and Policy, College of Public Health, The University of Iowa KEITH MUELLER [email protected] Department of Health Management and Policy, College of Public Health, The University of Iowa (corresponding author) ABSTRACT. There has been a significant decline in the number of independently owned rural pharmacies serving non-metropolitan areas, thereby limiting access to pharmaceutical services for rural residents, particularly for those most vulnerable and in need of these services. The use of telepharmacy is one potential solution to this problem. Telepharmacies deliver pharmaceutical care to outpatients at a distance via telecommunication and other advanced technologies. This study identifies rules and laws enacted by states authorizing the use of community telepharmacy initiatives within their respective jurisdictions. As of August 2016, the use of telepharmacy was authorized, in varying capacities, in 23 states (46%). Pilot program development that could apply to telepharmacy initiatives was authorized by six states (12%). Waivers to administrative or legislative pharmacy practice requirements that could allow for telepharmacy initiatives were permitted in five states (10%). Nearly one-third of the states (16, or 32%) did not authorize the use of telepharmacy, nor did they authorize the pursuit of telepharmacy initiatives via pilot programs or waivers. Keywords: telepharmacy; rule; statute; rural; community; outpatient How to cite: Tzanetakos, George, Fred Ullrich, and Keith Mueller (2018). -

Health Science: Biomedicine Public Service Endorsement

INNOVATE • COLLABORATE • EDUCATE • INNOVATE • COLLABORATE • EDUCATE Health Science: Biomedicine Public Service Endorsement Career Pathways • Biochemist • Biomedical Engineer • Biophysicist • Physician, Surgeon Certifications / Certificate Options • CPR • OSHA Program Highlights Biomedical engineering represents new areas of medical research and • Pathogen Analysis product development; biomedical engineers’ work helps pave the way • Human Anatomy & Physiology for new ways to help treat injuries and diseases. As medicine is a field • DNA / Genomics with vast numbers of specific disciplines, there are many different sub- • Laboratory Procedures fields in which biomedical engineers work. Some work to improve and • Dissection develop new machinery, such as robotic surgery equipment; others • Grow and Culture Bacteria endeavor to create better, more reliable replacement limbs (or parts • Real World Research which help existing limbs function better, such as joint replacements). • Learn to Treat Patients New and more comfortable patient beds, monitoring equipment, and electronics are also products that often begin as concepts from the CTSO(s) biomedical engineer’s or involve some level of input from them. • HOSA - Future Health Professionals KISD Biomedical Program: Program Fees / Requirements Biomedicine classes in KISD aim to prepare students to enter the • HOSA membership (Optional) health care field by giving them a foundation in real world problems, medical treatments, and a better understanding of the human body. Program Location Students will investigate causes and treatments of diseases that R Course(s) available at CHS affect the entire world as well as ones found in our own community. R Course(s) available at FRHS Students learn advanced techniques used in hospitals and research R Course(s) available at KHS labs and will become familiar with protocols used by doctors and R Course(s) available at TCHS researchers today. -

Glossary of Terms for Organ Donation and Transplantation

Glossary of Terms for Organ Donation and Transplantation Technical Terms for Donation and Transplantation Appropriate Term Inappropriate Term “recover” organs “harvest” organs “recovery” of organs “harvesting” of organs “donation” of organs “harvesting” of organs “mechanical” or “ventilator” support “life” support “donated organs and tissues” “body parts” “deceased” donor “cadaveric” donor “deceased” donation “cadaveric” donation “registered as a donor” “signed a donor card” (antiquated) Blood Type One of four groups (A, B, AB or O) into which blood is classified. Blood types are based on differences in molecules (proteins and carbohydrates) on the surface of red blood cells. Candidate A person registered on the organ transplant waiting list. Criteria (Medical Criteria) A set of clinical or biologic standards or conditions that must be met. Deceased Donor A patient who has been declared dead using either the brain death or cardiac death criteria and from whom at least one solid organ or some amount of tissue is recovered for the purpose of organ transplantation. Donor A deceased donor from whom at least one organ or some amount of tissue is recovered for the purpose of transplantation. A living donor is one who donates an organ or segment of an organ (such as a kidney or portion of their liver) for the intent of transplantation. Living Donation Situation in which a living person gives an organ or a portion of an organ for use in a transplant. A kidney, portion of a liver, lung or intestine may be donated. Living Donor A living person who donates an organ for transplantation, such as a kidney or a segment of the lung, liver or intestine. -

Specialty Pharmacy Drug List

Specialty Pharmacy Drug List Our Specialty Pharmacy provides patients with comprehensive support services and coordinated delivery related to high-cost oral, inhaled or injectable specialty medications, used to treat complex conditions. We are your single source for high-touch patient care management to control side effects, patient support and education to ensure compliance or continued treatment, and specialized handling and distribution of medications directly to the patient or care provider. Specialty medications may be covered under either the medical or pharmacy benefit. Please consult your insurance documentation to determine which benefit covers these medications. We offer a broad specialty medication list containing nearly 500 drugs, covering 42 therapeutic categories and specialty disease states. This list is updated with new information each quarter. Characteristics of Specialty Medications “Specialty” medications are defined as high-cost oral or injectable medications used to treat complex chronic conditions. These are highly complex medications, typically biology-based, that structurally mimic compounds found within the body. High-touch patient care management is usually required to control side effects and ensure compliance. Specialized handling and distribution are also necessary to ensure appropriate medication administration. Medications must have at least one of the following characteristics in order to be classified as a specialty medication by Magellan Rx Management. High Cost High Complexity High Touch High-cost medications -

Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health Care SECTORAL SERVICES of MATHEMATICAL RESEARCH Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry for COMPANIES C/ Lope Gómez De Marzoa, S/N

Biomedicine, pharmacy and health care SECTORAL SERVICES OF MATHEMATICAL RESEARCH Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry FOR COMPANIES C/ Lope Gómez de Marzoa, s/n. Campus Vida | CP 15782 Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña) Tel. 881 813 373 | 881 813 223 [email protected] | www.math-in.net math- in Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health Care Specialized services Mathematics is an effective tool with proven ability to Biomedicine, Pharmacy and Health industries bring meet the demands and needs of businesses. In Spain, together the supply of 29 research groups of the i-MATH Biomedicine and Pharmacy many innovative solutions emerged from the experience project, of which up to 20 have proven experience from gained by research groups in this field through successful having effectively carried out consulting activities, training • Analysis and design of experiments. • Studies of efficacy and safety of treatments. partnerships with industry over the years. All those courses and other collaborations. The details of these • Characterization/grading of pharmaceutical and medical waste. encouraging cases support its potential in offering an groups can be found in the 'Sectors' section of the • Modelling of mortality tables. increasingly sophisticated and complete service to the platform www.math-in.net. • Numerical simulation of fractures, dental implants and orthodontic brackets. industry. • Biomechanics. Bones formation. The mathematical technology services provided in this • Bioinformatics. • Mathematical Biology. Synthetic Biology. The Spanish Network for Mathematics & Industry sector can be broken down into two blocks (on the one • Computational design of proteins. (math-in) is a stable platform that continues the work hand, Biomedicine and Pharmacy and, on the other • Metabolism. -

Planning for Pharmacy School

CENTER FOR CAREER & PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT Planning for Pharmacy School Why Pharmacy? nutrition support. Pharmacists have also been instrumental in establishing many of the poison information and control centers Pharmacy is a career that offers great benefits, flexible work across the country. schedules, outstanding growth opportunities, profit sharing, and much more. If you enjoy working with people, excel in science, and would like a rewarding healthcare career, you may want to Career Options in Pharmacy: consider pharmacy. Academic pharmacy A well-rounded career: Pharmacy is a blend of science, Community practice healthcare, direct patient contact, computer technology, and business. Government agencies A vital part of the healthcare system: Pharmacists play an Hospice and home care integral role in improving patient’s health through the Hospital and institutional practice medicine and information they provide. Long-term care or consulting pharmacy Outstanding opportunities: There is an increasing need for Managed care pharmacy pharmacists in a wide variety of occupational settings. Medical and scientific publishing Excellent earning potential: Pharmacy is one of the most Pharmaceutical industry/sciences financially rewarding careers. Pharmacy law A trusted profession: Pharmacists are consistently ranked as Trade or professional associations one of the most highly trusted professionals because of the care and service they provide (according to data by Wirthlin Uniformed (public health) services Worldwide and Gallup International). Many pharmacists spend most of their workday on their feet. Community and hospital pharmacies are often open for extended The Pharmacy Profession hours or around the clock, so pharmacists may work nights, Although pharmacists are known as professionals whose primary weekends, and holidays.