The Jewish Topic in the Soviet Media: Political Environment, Priorities and Heroes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930S

Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Ariel Mae Lambe All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cuban Antifascism and the Spanish Civil War: Transnational Activism, Networks, and Solidarity in the 1930s Ariel Mae Lambe This dissertation shows that during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) diverse Cubans organized to support the Spanish Second Republic, overcoming differences to coalesce around a movement they defined as antifascism. Hundreds of Cuban volunteers—more than from any other Latin American country—traveled to Spain to fight for the Republic in both the International Brigades and the regular Republican forces, to provide medical care, and to serve in other support roles; children, women, and men back home worked together to raise substantial monetary and material aid for Spanish children during the war; and longstanding groups on the island including black associations, Freemasons, anarchists, and the Communist Party leveraged organizational and publishing resources to raise awareness, garner support, fund, and otherwise assist the cause. The dissertation studies Cuban antifascist individuals, campaigns, organizations, and networks operating transnationally to help the Spanish Republic, contextualizing these efforts in Cuba’s internal struggles of the 1930s. It argues that both transnational solidarity and domestic concerns defined Cuban antifascism. First, Cubans confronting crises of democracy at home and in Spain believed fascism threatened them directly. Citing examples in Ethiopia, China, Europe, and Latin America, Cuban antifascists—like many others—feared a worldwide menace posed by fascism’s spread. -

Course Handbook

SL12 Page 1 of 29 UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE DEPARTMENT OF SLAVONIC STUDIES PAPER SL12: SOCIALIST RUSSIA 1917-1991 HANDBOOK Daria Mattingly [email protected] SL12 Page 2 of 29 INTRODUCTION COURSE AIMS The course is designed to provide you with a thorough grounding in and advanced understanding of Russia’s social, political and economic history in the period under review and to prepare you for the exam, all the while fostering in you deep interest in Soviet history. BEFORE THE COURSE BEGINS Familiarise yourself with the general progression of Soviet history by reading through one or more of the following: Applebaum, A. Red Famine. Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017) Figes, Orlando Revolutionary Russia, 1891-1991 (2014) Hobsbawm, E. J. The Age of Extremes 1914-1991 (1994) Kenez, Peter A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End (2006) Lovell, Stephen The Soviet Union: A Very Short Introduction (2009) Suny, Ronald Grigor The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States (2010) Briefing meeting: There’ll be a meeting on the Wednesday before the first teaching day of Michaelmas. Check with the departmental secretary for time and venue. It’s essential that you attend and bring this handbook with you. COURSE STRUCTURE The course comprises four elements: lectures, seminars, supervisions and reading. Lectures: you’ll have sixteen lectures, eight in Michaelmas and eight in Lent. The lectures provide an introduction to and overview of the course, but no more. It’s important to understand that the lectures alone won’t enable you to cover the course, nor will they by themselves prepare you for the exam. -

Television and Politics in the Soviet Union by Ellen Mickiewicz TELEVISION and AMERICA's CHILDREN a Crisis of Neglect by Edward L

SPLIT SIGNALS COMMUNICATION AND SOCIETY edited by George Gerbner and Marsha Seifert IMAGE ETHICS The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film, and Television Edited by Larry Gross, John Stuart Katz, and Jay Ruby CENSORSHIP The Knot That Binds Power and Knowledge By Sue Curry Jansen SPLIT SIGNALS Television and Politics in the Soviet Union By Ellen Mickiewicz TELEVISION AND AMERICA'S CHILDREN A Crisis of Neglect By Edward L. Palmer SPLIT SIGNALS Television and Politics in the Soviet Union ELLEN MICKIEWICZ New York Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1988 Oxford University Press Oxford New York Toronto Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi Petaling Jaya Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo Nairobi Dar es Salaam Cape Town Melbourne Auckland and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1988 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of Oxford University Press. Mickiewicz, Ellen Propper. Split signals : television and politics in the Soviet Union / Ellen Mickiewicz. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-505463-6 1. Television broadcasting of news—Soviet Union. 2. Television broadcasting—Social aspects—Soviet Union. 3. Television broadcasting—Political aspects—Soviet Union. 4. Soviet Union— Politics and government—1982- I. Title. PN5277.T4M53 1988 302.2'345'0947—dc!9 88-4200 CIP 1098 7654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Preface In television terminology, broadcast signals are split when they are divided and sent to two or more locations simultaneously. -

Soviet Youth on the March: the All-Union Tours of Military Glory, 1965–87

This is a repository copy of Soviet Youth on the March: The All-Union Tours of Military Glory, 1965–87. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/96606/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Hornsby, R (2017) Soviet Youth on the March: The All-Union Tours of Military Glory, 1965–87. Journal of Contemporary History, 52 (2). pp. 418-445. ISSN 0022-0094 https://doi.org/10.1177/0022009416644666 © 2016, The Author. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Journal of Contemporary History. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Soviet Youth on the March: the All-Union Tours of Military Glory, 1965-87 ‘To the paths, friends, to the routes of military glory’1 The first train full of young people pulled into Brest station from Moscow at 10.48 on the morning of 18 September 1965. -

The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol

The Defence of Madrid: The Spanish Communist Party in the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), Vol. Amanda Marie Spencer Ph. D. History Department of History, University of Sheffield June 2006 i Contents: - List of plates iii List of maps iv Summary v Introduction 5 1 The PCE during the Second Spanish Republic 17 2 In defence of the Republic 70 3 The defence of Madrid: The emergence of communist hegemony? 127 4 Hegemony vs. pluralism: The PCE as state-builder 179 5 Hegemony challenged 229 6 Hegemony unravelled. The demise of the PCE 274 Conclusion 311 Appendix 319 Bibliography 322 11 Plates Between pp. 178 and 179 I PCE poster on military instruction in the rearguard (anon) 2a PCE poster 'Unanimous obedience is triumph' (Pedraza Blanco) b PCE poster'Mando Unico' (Pedraza Blanco) 3 UGT poster'To defend Madrid is to defend Cataluna' (Marti Bas) 4 Political Commissariat poster'For the independence of Spain' (Renau) 5 Madrid Defence Council poster'First we must win the war' (anon) 6a Political Commissariat poster Training Academy' (Canete) b Political Commissariat poster'Care of Arms' (anon) 7 lzquierda Republicana poster 'Mando Unico' (Beltran) 8 Madrid Defence Council poster'Popular Army' (Melendreras) 9 JSU enlistment poster (anon) 10 UGT/PSUC poster'What have you done for victory?' (anon) 11 Russian civil war poster'Have you enlisted as a volunteer?' (D.Moor) 12 Poster'Sailors of Kronstadt' (Renau) 13 Poster 'Political Commissar' (Renau) 14a PCE Popular Front poster (Cantos) b PCE Popular Front poster (Bardasano) iii Maps 1 Central Madrid in 1931 2 Districts of Madrid in 1931 2 3 Province of Madrid 3 4 District of Cuatro Caminos 4 iv Summary The role played by the Spanish Communist Party (Partido Comunista de Espana, PCE) during the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 remains controversial to this day. -

Dubious Means to Final Solutions: Extracting Light from the Darkness of Ein Führer and Brother Number One

Florida State University Law Review Volume 31 Issue 1 Article 5 2003 Dubious Means to Final Solutions: Extracting Light From the Darkness of Ein Führer and Brother Number One Román Ortega-Cowan [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Román Ortega-Cowan, Dubious Means to Final Solutions: Extracting Light From the Darkness of Ein Führer and Brother Number One, 31 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2003) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol31/iss1/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW DUBIOUS MEANS TO FINAL SOLUTIONS: EXTRACTING LIGHT FROM THE DARKNESS OF EIN FÜHRER AND BROTHER NUMBER ONE Román Ortega-Cowan VOLUME 31 FALL 2003 NUMBER 1 Recommended citation: Román Ortega-Cowan, Dubious Means to Final Solutions: Extracting Light From the Darkness of Ein Führer and Brother Number One, 31 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 163 (2003). DUBIOUS MEANS TO FINAL SOLUTIONS: EXTRACTING LIGHT FROM THE DARKNESS OF EIN FÜHRER AND BROTHER NUMBER ONE ROMÁN ORTEGA-COWAN* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 164 II. TUNING THE PIANO ........................................................................................... 165 A. The Players: The German Nazis and Cambodian Khmer Rouge .............. 165 B. A Single Word, Eternal Dread: Genocide................................................... 166 1. Lemkin’s Quest..................................................................................... 166 2. Room for One More: Political Groups .................................................. 168 C. Turning Principles into Action: The Legal System ................................... -

BETWEEN CREATION and CRISIS: SOVIET MASCULINITIES, CONSUMPTION, and BODIES AFTER STALIN by Brandon Gray Miller a DISSERTATION Su

BETWEEN CREATION AND CRISIS: SOVIET MASCULINITIES, CONSUMPTION, AND BODIES AFTER STALIN By Brandon Gray Miller A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT BETWEEN CREATION AND CRISIS: SOVIET MASCULINITIES, CONSUMPTION, AND BODIES AFTER STALIN By Brandon Gray Miller The Soviet Union of the 1950s and 1960s existed in a transitional state, emerging recently from postwar reconstruction and on a path toward increasing urbanity, consumer provisioning, and technological might. Modernizing rhetoric emphasized not only these spatial and material transformations, but also the promise of full-fledged communism’s looming arrival. This transformational ethos necessitated a renewal of direct attempts to remold humanity. Gender equality—or, at the very least, removing bourgeois strictures on women—remained a partially unfulfilled promise. Technological advances and the development of Soviet industrial capacity offered a new means of profoundly altering the lives of Soviet men and women. As other scholars have noted, Soviet women were the most obvious targets of these campaigns, but they were not alone in these projects. This dissertation argues that the Soviet state also directed intensive campaigns to remodel male consumptive and bodily practices in order to rid them of politically and socially destructive tendencies, making them fit for the modern socialist civilization under construction. Rooted in, but divergent from, Bolshevik novyi byt campaigns and Stalinist kul’turnost efforts, Soviet authorities actively sought to craft productive male citizens of a modern mold freed of the rough and coarse habits associated with working-class and village masculinities. Many of men targeted in these campaigns fell short of these stated aims. -

Great Patriotic War: 80 Years Since the Beginning

№134/06 (5005) Russkaya Mysl Founded in 1880 June 2021 Russian/English www.RussianMind.com №134/06 (5005). Июнь 2021, June 2021, Russian/English 2021, June №134/06 (5005). Июнь GREAT PATRIOTIC WAR: 80 YEARS SINCE THE BEGINNING Not for sale Russian Mind No134/06(5005), EDITOR’S LE ER JUNE 2021 HEAD OF THE EDITORIAL BOARD Victor Loupan FACE OF WAR EDITORIAL BOARD Anatoly Adamishin Metropolitan Anthony Rene Guerra Dmitry Shakhovskoy Peter Sheremetev Alexander Troubetskoy Sergey Yastrzhembsky DIRECTOR OF DEVELOPMENT Alexander Mashkin [email protected] EXECUTIVE EDITOR Karina Enfenjyan [email protected] POLITICAL EDITOR: Vyacheslav Katamidze CREATIVE PRODUCER: Vasily Grigoriev [email protected] nature, with arms, legs, a semblance of DESIGN Yuri Nor a brain, with eyes and a mouth. Yet this [email protected] terrible creature is only partially hu- ADVERTISEMENT: man. It has facial features similar to hu- [email protected] man ones, however a subhuman is po- DISTRIBUTION: sitioned spiritually and psychologically [email protected] lower than any animal. ere is a chaos SUBSCRIBTION: of wild, unbridled passions inside this [email protected] or the second month in a row, the creature: an unnamed need to destroy, Fmain theme of our issue is war! Or the most primitive desires and undis- ADDRESS: 47 avenue Hoche, 75008, Paris, France. rather, the memory of the war. Every guised meanness”. E-mail: [email protected] year on May 9 we celebrate Victory 62 countries with a total population COVER: Day, the greatest of our great victories. of 1.7 billion people participated in RIA Novosti Usually we miss to recall the beginning World War II. -

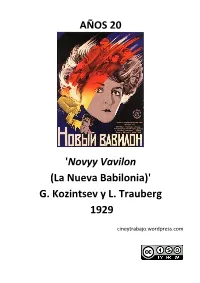

Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G

AÑOS 20 'Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G. Kozintsev y L. Trauberg 1929 cineytrabajo.wordpress.com Título original: Новый Вавилон/Novyy Vavilon; URSS, 1929; Productora: Sovkino; Director: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg. Fotografía: Andrei Moskvin (Blanco y negro); Guión: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg; Reparto: David Gutman, Yelena Kuzmina, Andrei Kostrichkin, Sofiya Magarill, A. Arnold, Sergei Gerasimov, Yevgeni Chervyakov, Pyotr Sobolevsky, Yanina Zhejmo, Oleg Zhakov, Vsevolod Pudovkin; Duración: 120′ “*...+¡La Comuna, exclaman, pretende abolir la propiedad, base de toda civilización! Sí, caballeros, la Comuna pretendía abolir esa propiedad de clase que convierte el trabajo de muchos en la riqueza de unos pocos. La Comuna aspiraba a la expropiación de los expropiadores.*...+” ¹ (Karl Marx) Sinopsis Ambientada en el París de 1870-1871, ‘La nueva Babilonia’ nos cuenta la historia de la instauración de la Comuna de París por parte de un grupo de hombres y mujeres que no quieren aceptar la capitulación del Gobierno de París ante Prusia en el marco de la guerra franco-prusiana. Louise, dependienta de los almacenes “La nueva Babilonia”, va a ser una de las más apasionadas defensoras de la Comuna hasta su derrocamiento en mayo de 1871. Comentario En 1929, Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg, dos de los creadores y difusores de la Fábrica del Actor Excéntrico (FEKS), escribieron y dirigieron la que se considera su obra conjunta de madurez: ‘Novyy Vavilon (La nueva Babilonia)’. Como muchas otras obras soviéticas se sirven de un hecho histórico real para exaltar la Revolución, pero la peculiaridad de la película de Trauberg y Kozintsev reside en que no sólo se remontan muchos años atrás en el tiempo, sino que además cambian de ubicación, situando la acción en la época de la guerra franco-prusiana de 1870 y la instauración de la Comuna de París al año siguiente. -

BASEES Sampler

R O U T L E D G E . TAYLOR & FRANCIS Slavonic & East European Studies A Chapter and Journal Article Sampler www.routledge.com/carees3 Contents Art and Protest in Putin's Russia by Laurien 1 Crump Introduction Freedom of Speech in Russia edited by Piotr 21 Dutkiewicz, Sakwa Richard, Kulikov Vladimir Chapter 8: The Putin regime: patrimonial media The Capitalist Transformation of State 103 Socialism by David Lane Chapter 11: The move to capitalism and the alternatives Europe-Asia Studies 115 Identity in transformation: Russian speakers in Post- Soviet Ukrane by Volodymyr Kulyk Post-Soviet Affairs 138 The logic of competitive influence-seeking: Russia, Ukraine, and the conflict in Donbas by Tatyana Malyarenko and Stefan Wolff 20% Discount Available Enjoy a 20% discount across our entire portfolio of books. Simply add the discount code FGT07 at the checkout. Please note: This discount code cannot be combined with any other discount or offer and is only valid on print titles purchased directly from www.routledge.com. www.routledge.com/carees4 Copyright Taylor & Francis Group. Not for distribution. 1 Introduction It was freezing cold in Moscow on 24 December 2011 – the day of the largest mass protest in Russia since 1993. A crowd of about 100 000 people had gathered to protest against electoral fraud in the Russian parliamentary elections, which had taken place nearly three weeks before. As more and more people joined the demonstration, their euphoria grew to fever pitch. Although the 24 December demonstration changed Russia, the period of euphoria was tolerated only until Vladimir Putin was once again installed as president in May 2012. -

The Russian Cinematic Culture

Russian Culture Center for Democratic Culture 2012 The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the Slavic Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Bulgakova, O. (2012). The Russian Cinematic Culture. In Dmitri N. Shalin, 1-37. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/russian_culture/22 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Russian Culture by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Russian Cinematic Culture Oksana Bulgakova The cinema has always been subject to keen scrutiny by Russia's rulers. As early as the beginning of this century Russia's last czar, Nikolai Romanov, attempted to nationalize this new and, in his view, threatening medium: "I have always insisted that these cinema-booths are dangerous institutions. Any number of bandits could commit God knows what crimes there, yet they say the people go in droves to watch all kinds of rubbish; I don't know what to do about these places." [1] The plan for a government monopoly over cinema, which would ensure control of production and consumption and thereby protect the Russian people from moral ruin, was passed along to the Duma not long before the February revolution of 1917. -

Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Senior Theses and Projects Student Scholarship Spring 2014 Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt Emily Parsons Trinity College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Parsons, Emily, "Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev's Secret Speech, the Poznán Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt". Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2014. Trinity College Digital Repository, https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/theses/365 1 Re-Thinking U.S.-Soviet Relations in 1956: Nikita Khrushchev’s Secret Speech, the Poznań Revolt, the Return of Władysław Gomułka, and the Hungarian Revolt Emily Parsons History Department Senior Thesis Advisor: Samuel Kassow Trinity College 2013-2014 2 Table of Contents: Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Part One: The Chronology of the Events of the Cold War in 1956 12 Chapter 1: Do As I Say Not As I Do: Nikita Khrushchev’s Secret Speech 13 Chapter 2: The Eastern Bloc Begins to Crack: Poznań Revolt and Polish October 21 Chapter 3: Khrushchev Goes Back on His Word: The Hungarian Revolt of 1956 39 Part Two: The United States Reactions and Understanding of the Events of 1956 60 Chapter 4: Can Someone Please Turn on the Lights? It’s Dark in Here: United States Reactions to the Khrushchev’s Secret Speech 61 Chapter 5: “When They Begin to Crack, They Can Crack Fast.