Genealogies of Modernism Curatorial Practices of Comparing in the Exhibitions Cubism and Abstract Art and Documenta I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note Dear readers, Although Bauhaus is relevant throughout history, this German school of art remains an open issue in art, architecture, design, and communication, addressing the following question: To what extent is Bauhaus even possible nowadays? Thus, this was our question for the Art Style Magazine's Bauhaus Special Edition. Therefore, in an attempt to showcase some of the most important issues so our readers can attain a broad notion of this German school's legacy, our Editorial Team has been working diligently and participated in several significant events, talks, round tables, and exhibitions. The opening festival and construction of the Bauhaus Museum in Weimar, for example, offered a great view of the importance of the Bauhaus. Above all, in the sense of arts and crafts in connection with industry, this school outlined a relationship of teaching design from product development, consumption to the changes of living together. Recently, the so-called "Fishfilet scandal" – an attempt to prevent a live event by a German rock band – was an important facet in the discussion that the Bauhaus still plays a significant role in the political scene. As artists and politicians said, the ban on concerts means a "terrifying history" for Bauhaus-Dessau. A month ago, we heard news from a round table, and artistic interventions under the title "How political is the Bauhaus?". These talks had taken place in the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Cultures) in Berlin on January 19, 2019. It was part of the opening festival of Bauhaus's centenary and supported by the Senate Department for Culture and Europe. -

'A Collage of Globalization' in Documenta 11'S Exhibition

‘A Collage of Globalization’ in Documenta 11’s Exhibition Catalogue Antigoni Memou The 11th issue of Documenta — the recurring international exhibition of contemporary art that has been held in Kassel, Germany since 1955 — was conceived as a critical space, within which contemporary art and its relationship to postcolonialism and globalization could be problematized. Its sheer scale preceded any previous issues of Documenta: it took place over eighteen months from March 2001 to September 2002, was curated by Okwui Enwezor and five co-curators — Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez, Sarat Maharaj and Octavio Zaya — and consisted of five platforms staged in different world cities. The first four platforms were devised as community-based public discussions and workshops with film and video programmes in Vienna, Berlin, New Delhi, St Lucia, and Lagos, while the fifth one — the exhibition — took place in Kassel. These five themed platforms allowed eighty international contributors across many different disciplines to debate the challenges of contemporary democracy, issues of truth, reconciliation and justice, postcolonial cultural formations and global megacities.1 The primary aims underpinning all five platforms — despite the diversity and complexity of discourses and the range of artistic practices included — were to challenge Documenta’s Western-centrism, both in the spatial and in the cultural-historical sense, and to question universalizing conceptions of cultural and artistic modernity. Enwezor took the 9/11 events in New York as a starting point for rethinking an alternative postcolonial world, positing ‘Ground Zero’ as a symbolic site of 1 These discursive loci that preceded the exhibition in Kassel brought together a great number of collaborators, institutions and foundations, and were perceived as an integral part of the exhibition, rather than as supplementary or complimentary to it. -

Documenta 11

1/21/2015 Frieze Magazine | Archive | Documenta 11 Documenta 11 About this article Documenta 11 Published on 09/09/02 By Thomas McEvilley Each of artistic director Okwui Enwezor’s six co-curators - Sarat Maharaj, Octavio Zaya, Carlos Basualdo, Ute Meta Bauer, Susanne Ghez and Mark Nash - spoke briefly, followed by Enwezor himself. Maharaj identified the point of art today as ‘knowledge production’ and the point of this exhibition as ‘thinking the other’; Nash declared that the exhibition aimed to explore ‘issues of dislocation and migration’ (‘We’re all becoming transnational subjects’, he observed); Ghez stressed the unusual fact that as many as 70% of the works in the show were made explicitly for the Back to the main site occasion; Basualdo spoke of ‘establishing a new geography, or topology, of culture’; and Bauer spoke of ‘deterritorialization’. Finally, Enwezor began his reflections by referring to Chinua Achebe’s classic novel of pre-colonial Africa Things Fall Apart (1958). He spoke of the emergence of post-colonial identity, and said that he and his colleagues had aimed at something much larger than an art exhibition: they were seeking to find out what comes after imperialism. These remarks were significant because Documenta, along with the Venice Biennale, is one of the foremost venues at which the current cultural politics of the art world is laid out. In a sense the agenda proclaimed by these curators gave one a sense of déjà vu; or rather, it seemed not exactly to usher in a new era but to set a seal on an era first announced long ago. -

Documenta 5 Working Checklist

HARALD SZEEMANN: DOCUMENTA 5 Traveling Exhibition Checklist Please note: This is a working checklist. Dates, titles, media, and dimensions may change. Artwork ICI No. 1 Art & Language Alternate Map for Documenta (Based on Citation A) / Documenta Memorandum (Indexing), 1972 Two-sided poster produced by Art & Language in conjunction with Documenta 5; offset-printed; black-and- white 28.5 x 20 in. (72.5 x 60 cm) Poster credited to Terry Atkinson, David Bainbridge, Ian Burn, Michael Baldwin, Charles Harrison, Harold Hurrrell, Joseph Kosuth, and Mel Ramsden. ICI No. 2 Joseph Beuys aus / from Saltoarte (aka: How the Dictatorship of the Parties Can Overcome), 1975 1 bag and 3 printed elements; The bag was first issued in used by Beuys in several actions and distributed by Beuys at Documenta 5. The bag was reprinted in Spanish by CAYC, Buenos Aires, in a smaller format and distrbuted illegally. Orginally published by Galerie art intermedai, Köln, in 1971, this copy is from the French edition published by POUR. Contains one double sheet with photos from the action "Coyote," "one sheet with photos from the action "Titus / Iphigenia," and one sheet reprinting "Piece 17." 16 ! x 11 " in. (41.5 x 29 cm) ICI No. 3 Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Poster 33 x 23 " in. (84.3 x 60 cm) ICI /Documenta 5 Checklist page 1 of 13 ICI No. 4 Lawrence Weiner A Primer, 1972 Artists' book, letterpress, black-and-white 5 # x 4 in. (14.6 x 10.5 cm) Documenta Catalogue & Guide ICI No. 5 Harald Szeemann, Arnold Bode, Karlheinz Braun, Bazon Brock, Peter Iden, Alexander Kluge, Edward Ruscha Documenta 5, 1972 Exhibition catalogue, offset-printed, black-and-white & color, featuring a screenprinted cover designed by Edward Ruscha. -

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen

Danish Sixties Avant-Garde and American Minimal Art Max Ipsen “Act so that there is no use in a centre”.1 Gertrude Stein Denmark is peripheral in the history of minimalism in the arts. In an international perspective Danish artists made almost no contributions to minimalism, according to art historians. But the fact is that Danish artists made minimalist works of art, and they did it very early. Art historians tend to describe minimal art as an entirely American phenomenon. America is the centre, Europe the periphery that lagged behind the centre, imitating American art. I will try to query this view with examples from Danish minimalism. I will discuss minimalist tendencies in Danish art and literature in the 1960s, and I will examine whether one can claim that Danish artists were influenced by American minimal art. Empirical minimal art The last question first. Were Danish artists and writers influenced by American minimal art? The straight answer is no. The fact is that they did not know about American minimal art when they first made works, which we today can characterize as minimal art or minimalism. Minimalism was just starting to occur in America when minimalist works of art were made in Denmark. Some Danish artists, all of them linked up with Den eksperimenterende Kunstskole (The Experimenting School of Art), or Eks-skolen as the school is most often called, in Copenhagen, were employing minimalist techniques, and they were producing what one would tend to call minimalist works of art without knowing of international minimalism. One of these artists, Peter Louis-Jensen, years later, in 1986, in an interview explained: [Minimalism] came to me empirically, by experience, whereas I think that it came by cognition to the Americans. -

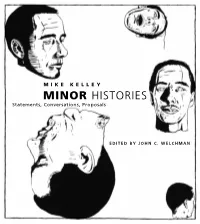

MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY Edited by John C

KELLEY MINOR HISTORIES Statements, Conversations, Proposals MIKE KELLEY edited by John C. Welchman What John C. Welchman calls the “blazing network of focused conflations” from which Mike Kelley’s styles are generated is on display in all its diversity in this second volume of his writings. The first volume, Foul Perfection, contained thematic essays and writings about other artists; this collection concentrates on Kelley’s own work, ranging from texts in “voices” that grew out of scripts for performance pieces to expository critical and autobiographical writings. Minor Histories organizes Kelley’s writings into five sections. “Statements” consists of twenty pieces produced MINOR between 1984 and 2002 (most of which were written to accompany exhibitions), including “Ajax,” which draws on MIKE KELLEY Homeric epic, Colgate-Palmolive advertising, and Longinus to present its eponymous hero; “Some Aesthetic High Points,” an exercise in autobiography that counters the standard artist bio included in catalogs and press releases; and a sequence of “creative writings” that use mass cultural tropes in concert with high art mannerisms—approximating in prose the visu- MINOR HISTORIES al styles that characterize Kelley’s artwork. “Video Statements and Proposals” are introductions to videos made by Kelley and other artists, including Paul McCarthy and Bob Flanagan and Sheree Rose. “Image-Texts” offers writings that accom- Statements, Conversations, Proposals pany or are part of artworks and installations. This section includes “A Stopgap Measure,” Kelley’s zestful millennial essay in social satire, and “Meet John Doe,” a collage of appropriated texts. The section “Architecture” features a discussion of Kelley’s Educational Complex (1995) and an interview in which he reflects on the role of architecture in his work. -

Documenta14 in Ruins

Leiden University – Faculty of Humanities Academic Year 2018-2019 MA Thesis Arts and Culture Documenta14 in ruins th Participation and antiquity in the 14 edition of documenta Submitted by: Ilektra/Electra Karatza Student Number: s2253836 Email: [email protected] MA in Arts & Culture 2018-2019 Specialization: Contemporary Art in A Global Perspective Word Count: 16952 Supervisor: Helen Westgeest Second Reader: Ali Shobeiri Date: 28 June 2019 1 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………… 5 Chapter 1: Documenta14’s paradoxical aspirations……………… 10 1.1. The curatorial message………………………………... 10 1.2. Scholarly discourse……………………………………. 14 1.3. Commercial Publications……………………………… 18 Chapter 2: A parliament of bio-political resistance……………….. 25 2.1. The concept of the body in the Public Programs of Documenta…………………………………………… 26 2.2. The concept of space in 34 Excercises of Freedom…. 34 Chapter 3: Participation in the Parthenon of Books………………… 39 3.1. An ambivalence: The Parthenon as a symbol of free speech……………………………………….... 40 3.2. The participatory factor of the artwork………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………… 51 List of Figures………………………………………………………... 55 Bibliography…………………………………………………………... 58 2 Abstract The German exhibition documenta is inarguably one of the most well-known exhibitions worldwide and takes part every four to five years in Kassel (Germany). It is an exhibition with inherent political character since its first edition that happened in 1955. The topic discussed in this MA thesis, is the 14th edition of documenta and its partial re-location to Athens (Greece). This thesis is a critical examination of stereotypical assumptions about Greece’s past that were included in the discourse of the exhibition, and manifested through the public program Exercises of Freedom and the artwork The Parthenon of Books by Marta Minujín. -

Bauhaus-Documenta-2019-II-2.Pdf

documenta Untere Karlsstraße 4 [email protected] archiv D-34117 Kassel www.documenta-archiv.de T. +49 561 70727-6109 F. +49 561 70727-39 Kassel, May 14, 2019 Press invitation bauhaus | documenta. Vision and Brand May 24–September 8, 2019 Press conference and exhibition preview: May 23, 2019, 11.30am Neue Galerie Schöne Aussicht 1, 34117 Kassel Welcoming address Sabine Schormann, Director General documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH Reiner Finkeldey, President University of Kassel About the project Philipp Oswalt, curator (Professor for Architectural Theory and Design, University of Kassel) Exhibition tour with the curators Daniel Tyradellis and Philipp Oswalt Press information: The exhibition bauhaus | documenta. Vision and Brand reflects upon the two institutions Bauhaus and documenta for the first time in comparison. The 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus in 2019 offers an opportunity to view the development of the two institutions, both of which have become cultural brands, and simultaneously to critically examine them. To what extent have the brands remained true to themselves in terms of their commitment to innovation and progress? To what extent have they been appropriated to serve certain interests? Thus, the exhibition also offers a view of the role and function that art and culture can have in society today. Both Bauhaus, founded 100 years ago in Weimar, and documenta, mounted for the first time in 1955 in Kassel, stand today for a tradition of modernism and avant-garde in Germany, for visionary cultural brands with an international standing and the belief in artistic innovation and art’s ability to reform society. They both developed their own idealist values and have achieved almost popular international renown. -

Looted Art at Documenta 14 by Eleonora Vratskidou

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 2 (2018) A Review: Stories of wheels within wheels: looted art at documenta 14 by Eleonora Vratskidou While dOCUMENTA 13 (2012) reflected on the annihilation of cultural heritage, taking as a starting point the destruction of the two monumental Buddha statues in Bamiyan, Afghanistan, by the Taliban in 2001,1 the recent documenta 14 (2017) actively addressed the question of art theft and war spoliations, taking as its point of departure the highly controversial case of the Gurlitt art hoard. The circa 1,500 artworks uncovered in the possession of Cornelius Gurlitt (1934-2014), inherited from his father Hildebrand Gurlitt (1895-1956), one of the official art dealers of the Nazi regime, brought back to the surface aspects of a past that Germany is still in the process of coming to terms with. Initially, the intention of artistic director Adam Szymczyk had been to showcase the then unseen Gurlitt estate in the Neue Galerie in Kassel as part of documenta 14. Revisiting the tensed discussions on the status of the witness with regard to the historical experi- ence of the Holocaust (as addressed by Raul Hilberg, Dori Laub or Claude Lanzmann), Adam Szymczyk, in a conversation with the art historian Alexander Alberro and partici- pant artists Hans Haacke and Maria Eichhorn, reflected on plundered art works as “wit- nessing objects”, which in their material and visual specificity are able to give testament to an act of barbarism almost inexpressible by means of language.2 1 See mainly the text by artistic director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, On the Destruction of Art —or Conflict and Art, or Trauma and the Art of Healing, and the postcript to it, Dario Gamboni’s article World Herit- age: Shield or Target, in the exhibition catalogue edited by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev and Katrin Sauer- länder, The Book of Books (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2012), 282-295, as well as the commissioned project by Michael Rakowitz, What Dust Will Rise (2012). -

D Is for Documenta: Institutional Identity for a Periodic Exhibition by Kathryn M

d is for documenta The documenta Issue d is for documenta: institutional identity for a periodic exhibition by Kathryn M. Floyd Every five summers, Kassel, Germany is covered its typical boundaries in a display of global art spread over with signs and advertisements for what is billed out not only across the city, but also across the globe.4 as the most significant periodic exhibition of contem- porary art: documenta. [fig. 1] The publicity for the thirteenth edition in summer 2012 managed to attract over 905,000 visitors to this small Hessen city where they viewed hundreds of works by 194 global artists in ten venues and additional public spaces. Organizers dubbed the unassuming branding device commissioned for this enormous blockbuster a “non-logo.” Instead of producing a unique signet or single wordmark to distinguish the event from its twelve predecessors, the Milan-based firm Leftloft developed a “visual grammar” for writing the name in an infinite variety of typefaces. The rules dictated that 2 the name be written with “a lowercase ‘d’ while the rest of the letters will all be uppercase and followed Leftloft’s non-logo also suggested the nature and by the number thirteen in brackets.”1 The resulting history of the documenta institution, itself a “gram- wordmarks,2 including those used for official publica- mar” whose regularized five-year cycle, location, and tions and signage [fig. 2], conveyed dOCUMENTA focus on contemporary art are rewritten with fresh (13)’s “pluralist, imaginative, and cumulative” charac- leadership and artistic content twice a decade. The ter, and required “active engagement, attention, and a design also acknowledged the series’ history by certain amount of extra time on the keyboard.”3 This maintaining the lowercase “d” from the wordmark for challenging, inexhaustible, and flexible functionality the inaugural 1955 edition, a groundbreaking survey mirrored the exhibition’s enormity, which exploded of international modern art. -

Download-Bibliography.Pdf

MIKE KELLEY FOUNDATION FOR THE ARTS This bibliography was compiled by Eva Mayer Hermann for Mike Kelley (New York: Delmonico Books/Prestel 2013) and has been revised and updated by the Mike Kelley Foundation for the Arts. MONOGRAPHS, ARTIST’S BOOKS, AND OTHER PUBLICATIONS 1986 Kelley, Mike. Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile. Venice, California: New City Editions; New York, New York: Artists Space, 1986. Artist’s book published on the occasion of the 1985 group exhibition Art in the Anchorage. 1988 Kelley, Mike, John Miller, and Howard Singerman, eds. Mike Kelley: Three Projects: Half a Man, From My Institution to Yours, Pay For Your Pleasure. Chicago, Illinois: The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, 1988. Exh. cat. 1989 Knight, Christopher. Mike Kelley. Cologne, Germany: Jablonka Galerie, 1989. Exh. cat. 1990 Kelley, Mike. Reconstructed History. Cologne, Germany: Galerie Gisela Capitain; New York, New York: Thea Westreich, 1990. Artist’s book. 1991 Cruz, Amada. Mike Kelley: Half a Man. Washington, D.C.: Hirschhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 1991. Exh. cat. 1992 Bartman, William S., and Miyoshi Barosh, eds. Mike Kelley. New York, New York: Art Resources Transfer, 1992. Mike Kelley. Basel, Switzerland: Kunsthalle Basel; Frankfurt, Germany: Portikus; London, England: Institute of Contemporary Arts; Ostfildern, Germany: Edition Cantz. 1992. Exh. cat. Paul McCarthy / Mike Kelley:Heidi: Midlife Crisis Trauma Center and Negative Media-Engram Abreaction Release Zone. Vienna, Austria: Galerie Kinzinger, 1992. Exh. cat. 1993 Kelley, Mike. The Uncanny. Arnhem, The Netherlands: Gemeentemuseum, 1993. Published concurrently with the 1993 group exhibition Sonsbeek ’93. Exh. cat. Sussman, Elisabeth.