Iuiti J~I~I;I S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taper-Leaved Penstemon Plant Guide

Plant Guide Uses TAPER-LEAVED Pollinator habitat: Penstemon attenuatus is a source of pollen and nectar for a variety of bees, including honey PENSTEMON bees and native bumble bees, as well as butterflies and Penstemon attenuatus Douglas ex moths. Lindl. Plant Symbol = PEAT3 Contributed by: NRCS Plant Materials Center, Pullman, WA Bumble bee visiting a Penstemon attenuatus flower. Pamela Pavek Rangeland diversification: This plant can be included in seeding mixtures to improve the diversity of rangelands. Ornamental: Penstemon attenuatus is very attractive and easy to manage as an ornamental in urban, water-saving landscapes. Rugged Country Plants (2012) recommends placing P. attenuatus in the back row of a perennial bed, in rock gardens and on embankments. It is hardy to USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 4 (Rugged Country Plants 2012). Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description General: Figwort family (Scrophulariaceae). Penstemon attenuatus is a native, perennial forb that grows from a Penstemon attenuatus. Pamela Pavek dense crown to a height of 10 to 90 cm (4 to 35 in). Leaves are dark green, opposite and entire, however the Alternate Names margins of P. attenuatus var. attenuatus leaves are often, Common Alternate Names: taper-leaf penstemon, sulphur at least in part, finely toothed (Strickler 1997). Basal penstemon, sulphur beardtongue (P. attenuatus var. leaves are petiolate, up to 4 cm (1.5 in) wide and 17 cm (7 palustris), south Idaho penstemon (P. attenuatus var. -

Pollination by Deceit in Paphiopedilum Barbigerum (Orchidaceae): a Staminode Exploits the Innate Colour Preferences of Hoverflies (Syrphidae) J

Plant Biology ISSN 1435-8603 RESEARCH PAPER Pollination by deceit in Paphiopedilum barbigerum (Orchidaceae): a staminode exploits the innate colour preferences of hoverflies (Syrphidae) J. Shi1,2, Y.-B. Luo1, P. Bernhardt3, J.-C. Ran4, Z.-J. Liu5 & Q. Zhou6 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2 Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3 Department of Biology, St Louis University, St Louis, MO, USA 4 Management Bureau of Maolan National Nature Reserve, Libo, Guizhou, China 5 The National Orchid Conservation Center, Shenzhen, China 6 Guizhou Forestry Department, Guiyang, China Keywords ABSTRACT Brood site mimic; food deception; fruit set; olfactory cue; visual cue. Paphiopedilum barbigerum T. Tang et F. T. Wang, a slipper orchid native to southwest China and northern Vietnam, produces deceptive flowers that are Correspondence self-compatible but incapable of mechanical self-pollination (autogamy). The Y.-B. Luo, State Key Laboratory of Systematic flowers are visited by females of Allograpta javana and Episyrphus balteatus and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, (Syrphidae) that disperse the orchid’s massulate pollen onto the receptive Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20 Nanxincun, stigmas. Measurements of insect bodies and floral architecture show that the Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China. physical dimensions of these two fly species correlate with the relative posi- E-mail: [email protected] tions of the receptive stigma and dehiscent anthers of P. barbigerum. These hoverflies land on the slippery centralised wart located on the shiny yellow Editor staminode and then fall backwards through the labellum entrance. -

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017 A Publication of the Harvard University Herbaria Including The Journal of the Arnold Arboretum Arnold Arboretum Botanical Museum Farlow Herbarium Gray Herbarium Oakes Ames Orchid Herbarium ISSN: 1938-2944 Harvard Papers in Botany Initiated in 1989 Harvard Papers in Botany is a refereed journal that welcomes longer monographic and floristic accounts of plants and fungi, as well as papers concerning economic botany, systematic botany, molecular phylogenetics, the history of botany, and relevant and significant bibliographies, as well as book reviews. Harvard Papers in Botany is open to all who wish to contribute. Instructions for Authors http://huh.harvard.edu/pages/manuscript-preparation Manuscript Submission Manuscripts, including tables and figures, should be submitted via email to [email protected]. The text should be in a major word-processing program in either Microsoft Windows, Apple Macintosh, or a compatible format. Authors should include a submission checklist available at http://huh.harvard.edu/files/herbaria/files/submission-checklist.pdf Availability of Current and Back Issues Harvard Papers in Botany publishes two numbers per year, in June and December. The two numbers of volume 18, 2013 comprised the last issue distributed in printed form. Starting with volume 19, 2014, Harvard Papers in Botany became an electronic serial. It is available by subscription from volume 10, 2005 to the present via BioOne (http://www.bioone. org/). The content of the current issue is freely available at the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries website (http://huh. harvard.edu/pdf-downloads). The content of back issues is also available from JSTOR (http://www.jstor.org/) volume 1, 1989 through volume 12, 2007 with a five-year moving wall. -

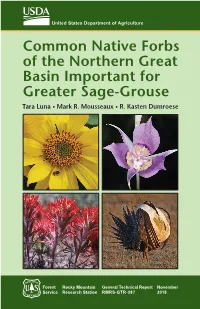

Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R

United States Department of Agriculture Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R. Mousseaux • R. Kasten Dumroese Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report November Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-387 2018 Luna, T.; Mousseaux, M.R.; Dumroese, R.K. 2018. Common native forbs of the northern Great Basin important for Greater Sage-grouse. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-387. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; Portland, OR: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Oregon–Washington Region. 76p. Abstract: is eld guide is a tool for the identication of 119 common forbs found in the sagebrush rangelands and grasslands of the northern Great Basin. ese forbs are important because they are either browsed directly by Greater Sage-grouse or support invertebrates that are also consumed by the birds. Species are arranged alphabetically by genus and species within families. Each species has a botanical description and one or more color photographs to assist the user. Most descriptions mention the importance of the plant and how it is used by Greater Sage-grouse. A glossary and indices with common and scientic names are provided to facilitate use of the guide. is guide is not intended to be either an inclusive list of species found in the northern Great Basin or a list of species used by Greater Sage-grouse; some other important genera are presented in an appendix. Keywords: diet, forbs, Great Basin, Greater Sage-grouse, identication guide Cover photos: Upper le: Balsamorhiza sagittata, R. -

The Inflorescence and Flowers of Dichrostachys Cinerea, W & A

THE INFLORESCENCE AND FLOWERS OF DICHROSTACHYS CINEREA, W & A BY C. S. VENKATESH (Department of Botany, University of Delhi, Delhi) Received April 14, 1951 (Communicated by Prof. P. Maheshwari, r.A.SC.) THE inflorescences of certain members of the sub-family Mimosoide~e bear polygamous flowers. Geitler (1927) has described this phenomenon in Neptunia oleracea. The results of a similar study of Dichrostachys cinerea, another member of the sub-family, are embodied in the present paper. This plant is of frequent occurrence in the dry forests of India and material collected on the Delhi Ridge last September by Prof. P. Maheshwari was very kindly passed on to me for study. Besides dissections of numerous flowers from several inflorescences, microtome sections of complete young spikes as well as of individual flowers were cut following the customary methods of infiltration and imbedding in paraffin. Some sections were stained with safranin and fast green and others with Heidenhain's iron-alum h~ematoxylin. OBSERVATIONS A portion of a flowering and fruiting twig of the plant is shown in Fig. 1. Exclusive of the stalk, approximately the upper half of the spicate inflorescence bears normal, perfect, bisexual flowers with the floral formula K (5), C (5), A 5, and G 1. The petals are subconnate towards their bases and are bright yellow in colour. The stamens have slender filiform fila- ments. The five stamens opposite the sepals are longer than those oppo- site the petals (Fig. 11). The dorsifixed anthers are four-celled, with the connective prolonged into a conspicuous, stipitate gland (Figs. 17, 18, 29). -

Bee-Mediated Pollen Transfer in Two Populations of Cypripedium Montanum Douglas Ex Lindley

Journal of Pollination Ecology, 13(20), 2014, pp 188-202 BEE-MEDIATED POLLEN TRANSFER IN TWO POPULATIONS OF CYPRIPEDIUM MONTANUM DOUGLAS EX LINDLEY Peter Bernhardt*1, Retha Edens-Meier2, Eric Westhus3, Nan Vance4 1Department of Biology, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 2Department of Educational Studies, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 3Center for Outcomes Research, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 4P.O. Box 282, Kooskia, ID 83539, USA Abstract—The conversion rate of flowers into fruit in C. montanum at two sites over four seasons was 52-85%, unusually high for a food mimic orchid. Comparative measurements of the trap-like labellum of C. montanum showed it was intermediate in size compared to measurements of six other Cypripedium spp. found in North America and China. While visitors to flowers of C. montanum represented three insect orders, at two sites, over four seasons only small- to medium-sized, solitary bees (5-10 mm in length) carried the pollen massulae. Bee-visitation occurred at both sites and began within 24-48 hours following labellum expansion. Female bees in the genus Lasioglossum (Halictidae) were the most common carriers of massulae. However, species of visiting bees differed between sites and years. At both sites the majority of bees entered and escaped from the labellum in less than 180 seconds and there was no significant difference between the times bees spent in the flowers at both sites. At the site on the Eastside Cascades of Central Oregon, there was no correlation between the length and width of a bee and the time it spent escaping from the basal openings. -

What Good Is a Sterile Stamen? by Peter Lesica from Kelseya, Summer 2002

What Good Is A Sterile Stamen? By Peter Lesica from Kelseya, Summer 2002 Penstemons are one of our favorite and most familiar groups of native plants. That’s understandable because there are lots of them and most have colorful, showy flowers. In fact, Penstemon is the largest genus of plants among those found only in North America. Of the 250 species, the majority occur in the western U.S. The great diversity of penstemons makes them a great group for gardening, but it also allows us to study how flowers evolve without having to go too far from home. Beardtongue is the common name applied to many members of the genus Penstemon. It refers to the fact that all penstemons have a sterile stamen called a "staminode" that is hairy to some extent in the majority of species. Penstemon flowers are pretty simple, so the staminode is easy to see. Just peel open the corolla. There are six slender, whitish stalks inside. Four have elongate sacs at their tips; these are the fertile stamens, and the sacs contain pollen. One of the two remaining stalks comes from the top of the ovary; this is the style that carries pollen tubes to the young seeds. The other sacless stalk is the staminode. Evolutionary biologists believe that the pollen-bearing function of the staminode was lost during the evolution of penstemon’s two-sided, two-lipped flower from more primitive, radially symmetrical tube flowers. Flowers of these less advanced groups have five functional stamens. But five doesn’t divide evenly into the two halves of the bilaterally symmetrical penstemon flower, so apparently the function of one of the five stamens was lost as flowers evolved toward being two-lipped. -

Quantitative Importance of Staminodes for Female Reproductive Success in Parnassia Palustris Under Contrasting Environmental Conditions

Color profile: Generic CMYK printer profile Composite Default screen View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk 49brought to you by CORE provided by Agder University Research Archive Quantitative importance of staminodes for female reproductive success in Parnassia palustris under contrasting environmental conditions Sylvi M. Sandvik and Ørjan Totland Abstract: The five sterile stamens, or staminodes, in Parnassia palustris act both as false and as true nectaries. They attract pollinators with their conspicuous, but non-rewarding tips, and also produce nectar at the base. We removed staminodes experimentally and compared pollinator visitation rate and duration and seed set in flowers with and with- out staminodes in two different populations. We also examined the relative importance of the staminode size to other plant traits. Finally, we bagged, emasculated, and supplementary cross-pollinated flowers to determine the pollination strategy and whether reproduction was limited by pollen availability. Flowers in both populations were highly depend- ent on pollinator visitation for maximum seed set. In one population pollinators primarily cross-pollinated flowers, whereas in the other the pollinators facilitated self-pollination. The staminodes caused increased pollinator visitation rate and duration to flowers in both populations. The staminodes increased female reproductive success, but only when pollen availability constrained female reproduction. Simple linear regression indicated a strong selection on staminode size, multiple regression suggested that selection on staminode size was mainly caused by correlation with other traits that affected female fitness. Key words: staminodes, insect activity, seed set, spatial variation, Parnassia palustris. Résumé : Chez le Parnassia palustris, les cinq étamines stériles, ou staminodes, agissent à la fois comme fausses et véritables nectaires. -

2020.05.22.111716.Full.Pdf

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.22.111716; this version posted December 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Serial Section-Based 3D Reconstruction of Anaxagorea Carpel Vasculature and 2 Implications for Integrated Axial-Foliar Homology of Carpels 3 4 Ya Li, 1,† Wei Du, 1,† Ye Chen, 2 Shuai Wang,3 Xiao-Fan Wang1,* 5 1 College of Life Sciences, Wuhan University, Wuhan 430072, China 6 2 Department of Environmental Art Design, Tianjin Arts and Crafts Vocational 7 College, Tianjin 300250, China 8 3 College of Life Sciences and Environment, Hengyang Normal University, 9 Hengyang 421001, China 10 *Author for correspondence. E-mail: [email protected] 11 † Both authors contributed equally to this work 12 13 Running Title: Integrated Axial-Foliar Homology of Carpel 14 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.22.111716; this version posted December 16, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 15 Abstract 16 The carpel is the basic unit of the gynoecium in angiosperms and one of the most 17 important morphological features differentiating angiosperms from gymnosperms; 18 therefore, carpel origin is of great significance in the phylogeny of angiosperms. 19 However, the origin of the carpel has not been solved. The more recent consensus 20 favors the interpretation that the ancestral carpel is the result of fusion between an 21 ovule-bearing axis and the phyllome that subtends it. -

Inflorescence and Flower Development in Costus Scaber (Costaceae)

Inflorescence and flower development in Costus scaber (Costaceae) By: BRUCE K. KIRCHOFF Kirchoff, B. K. 1988. Inflorescence and flower development in Costus scaber (Costaceae). Canadian Journal of Botany 62: 339-345. Made available courtesy of National Research Council Canada: http://rparticle.web- t.cisti.nrc.ca/rparticle/AbstractTemplateServlet?calyLang=eng&journal=cjb&volume=66&year= 1988&issue=2&msno=b88-054 ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: The inflorescence of Costus scaber terminates an erect axis of a sympodial rhizome system. Primary bracts are borne on the inflorescence in spiral monostichous phyllotaxy. One-flowered cincinni occur in the axils of these bracts. Each cincinnus consists of an axis bearing a terminal flower and a secondary bract on the anodic side of the flower. A tertiary bud forms in the axil of this bract but does not complete development. The inflorescence terminates by cessation of growth of the apex and precocious development of the primary bracts. Floral organs are formed sequentially beginning with the calyx, and continuing with the corolla and inner androecial whorl, outer androecial whorl, and gynoecium. All flower parts, except for the calyx, originate from a ring primordium. Regions of this primordium separate to form the corolla and inner androecial members. It was not possible to determine the sequence of androecial member formation. The labellum is composed of five androecial members, three from the outer whorl and two from the inner. The third member of the inner whorl forms the stamen and its petaloid appendage. The gynoecium forms from three conduplicate primordia. -

Illustrated Glossary of Botanical Terms

ILLUSTRATED GLOSSARY OF BOTANICAL TERMS FLORA OF THE CHICAGO REGION A Floristic and Ecological Synthesis (Wilhelm & Rericha, 2017) Published by the Indiana Academy of Science (IAS) September 20, 2020 The glossary for the 4th edition of Plants of the Chicago Region (Swink & Wilhelm, 1994) had nearly 200 individual drawings on 12 intercalated plates. These illustrations were popular and a useful feature. However, as the page count in the follow-up book, Flora of the Chicago Region (FCR), needed to be reduced, the decision was made not to include an illustrated glossary. In an attempt to make FCR a more useful educational tool, it was recently decided to publish an adjunct illustrated glossary and to post it on the website maintained by the Conservation Research Institute (CRI). The new glossary has been expanded substantially, providing double the number of individual illustrations and terms. The glossary is available for use without charge. We merely ask that all use of these illustrations and associated glossary be limited to educational and non-commercial activities, and that the IAS, FCR and CRI each be credited in all use. THE ARTISTS: Paul Nelson penned the drawings used in the 4th edition of PCR. Mary Marguerite Lowther created the line art used for each genus in FCR. Kathleen Marie Garness produced the illustrations used for the addended FCR glossary. We applaud their talent. EDITOR’S NOTE: The senior author is a master key writer—the best I know. His keys are clean and precise. Anyone truly interested in learning plants (i.e., distinguishing species) will encounter and at some point will need to know how to use a dichotomous key, which will require a familiarity with botanical terminology. -

ROYAL PENSTEMON Penstemon Speciosus Douglas Ex Lindl

ROYAL PENSTEMON Penstemon speciosus Douglas ex Lindl. Plantaginaceae – Plantain family Nancy L. Shaw & Corey L. Gucker | 2018 ORGANIZATION NOMENCLATURE Royal penstemon (Penstemon speciosus Names, subtaxa, chromosome number(s), hybridization. Douglas ex Lindl.) is a member of family Plantaginageae, the plantain family, subgenus Habroanthus (Keck) Crossw., section Glabri (Rydb.) Penn. Previously placed in the family Range, habitat, plant associations, elevation, soils. Scrophulariaceae, the genus Penstemon was moved to Plantaginaceae based on DNA sequencing studies (see Olmstead 2002). Life form, morphology, distinguishing characteristics, reproduction. NRCS Plant Code. PESP (USDA NRCS 2017). Synonyms. Penstemon speciosum Douglas Growth rate, successional status, disturbance ecology, importance to ex Lindl., P. glaber var. occidentalis A. Gray, animals/people. P. glaber var. speciosus Regel, P. glaber f. speciosus Voss, P. kennedyi A. Nels., P. speciosus subsp. kennedyi Keck, P. piliferus Current or potential uses in restoration. A.A. Heller, P. speciosus var. piliferus Munz & I.M. Johnston, P. rex Nels. & Macbr, P. perpulcher var. pandus Nels & Macbr., P. Seed sourcing, wildland seed collection, seed cleaning, storage, pandus Nels. & Macbr., P. deserticola Piper, P. testing and marketing standards. glaber sensu A. Gray, P. glaber var. utahensis sensu Jepson (Cronquist et al. 1984). Recommendations/guidelines for producing seed. Common Names. Royal penstemon, royal beardtongue, sagebrush beardtongue, sagebrush penstemon, showy penstemon (Cronquist et al. 1984; Tilley et al. 2009; Recommendations/guidelines for producing planting stock. LBJWC 2017; USDA NRCS 2017). Chromosome Number. The species is diploid, 2n = 16 (Crosswhite 1967; Hickman 1993). Recommendations/guidelines, wildland restoration successes/ failures. Hybridization. Specific information on hybridization of royal penstemon with other Primary funding sources, chapter reviewers.