Determining the Nativity of Plant Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45Th Anniversary Year

VOLUME 45, NO. 1 Spring 2021 Journal of the Douglasia WASHINGTON NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY th To promote the appreciation and 45 conservation of Washington’s native plants Anniversary and their habitats through study, education, Year and advocacy. Spring 2021 • DOUGLASIA Douglasia VOLUME 45, NO. 1 SPRING 2021 journal of the washington native plant society WNPS Arthur R. Kruckberg Fellows* Clay Antieau Lou Messmer** President’s Message: William Barker** Joe Miller** Nelsa Buckingham** Margaret Miller** The View from Here Pamela Camp Mae Morey** Tom Corrigan** Brian O. Mulligan** by Keyna Bugner Melinda Denton** Ruth Peck Ownbey** Lee Ellis Sarah Reichard** Dear WNPS Members, Betty Jo Fitzgerald** Jim Riley** Mary Fries** Gary Smith For those that don’t Amy Jean Gilmartin** Ron Taylor** know me I would like Al Hanners** Richard Tinsley Lynn Hendrix** Ann Weinmann to introduce myself. I Karen Hinman** Fred Weinmann grew up in a small town Marie Hitchman * The WNPS Arthur R. Kruckeberg Fellow Catherine Hovanic in eastern Kansas where is the highest honor given to a member most of my time was Art Kermoade** by our society. This title is given to Don Knoke** those who have made outstanding spent outside explor- Terri Knoke** contributions to the understanding and/ ing tall grass prairie and Arthur R. Kruckeberg** or preservation of Washington’s flora, or woodlands. While I Mike Marsh to the success of WNPS. Joy Mastrogiuseppe ** Deceased love the Midwest, I was ready to venture west Douglasia Staff WNPS Staff for college. I earned Business Manager a Bachelor of Science Acting Editor Walter Fertig Denise Mahnke degree in Wildlife Biol- [email protected] 206-527-3319 [email protected] ogy from Colorado State Layout Editor University, where I really Mark Turner Office and Volunteer Coordinator [email protected] Elizabeth Gage got interested in native [email protected] plants. -

Conserving Europe's Threatened Plants

Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Conserving Europe’s threatened plants Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation By Suzanne Sharrock and Meirion Jones May 2009 Recommended citation: Sharrock, S. and Jones, M., 2009. Conserving Europe’s threatened plants: Progress towards Target 8 of the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation Botanic Gardens Conservation International, Richmond, UK ISBN 978-1-905164-30-1 Published by Botanic Gardens Conservation International Descanso House, 199 Kew Road, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3BW, UK Design: John Morgan, [email protected] Acknowledgements The work of establishing a consolidated list of threatened Photo credits European plants was first initiated by Hugh Synge who developed the original database on which this report is based. All images are credited to BGCI with the exceptions of: We are most grateful to Hugh for providing this database to page 5, Nikos Krigas; page 8. Christophe Libert; page 10, BGCI and advising on further development of the list. The Pawel Kos; page 12 (upper), Nikos Krigas; page 14: James exacting task of inputting data from national Red Lists was Hitchmough; page 16 (lower), Jože Bavcon; page 17 (upper), carried out by Chris Cockel and without his dedicated work, the Nkos Krigas; page 20 (upper), Anca Sarbu; page 21, Nikos list would not have been completed. Thank you for your efforts Krigas; page 22 (upper) Simon Williams; page 22 (lower), RBG Chris. We are grateful to all the members of the European Kew; page 23 (upper), Jo Packet; page 23 (lower), Sandrine Botanic Gardens Consortium and other colleagues from Europe Godefroid; page 24 (upper) Jože Bavcon; page 24 (lower), Frank who provided essential advice, guidance and supplementary Scumacher; page 25 (upper) Michael Burkart; page 25, (lower) information on the species included in the database. -

Taper-Leaved Penstemon Plant Guide

Plant Guide Uses TAPER-LEAVED Pollinator habitat: Penstemon attenuatus is a source of pollen and nectar for a variety of bees, including honey PENSTEMON bees and native bumble bees, as well as butterflies and Penstemon attenuatus Douglas ex moths. Lindl. Plant Symbol = PEAT3 Contributed by: NRCS Plant Materials Center, Pullman, WA Bumble bee visiting a Penstemon attenuatus flower. Pamela Pavek Rangeland diversification: This plant can be included in seeding mixtures to improve the diversity of rangelands. Ornamental: Penstemon attenuatus is very attractive and easy to manage as an ornamental in urban, water-saving landscapes. Rugged Country Plants (2012) recommends placing P. attenuatus in the back row of a perennial bed, in rock gardens and on embankments. It is hardy to USDA Plant Hardiness Zone 4 (Rugged Country Plants 2012). Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g., threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description General: Figwort family (Scrophulariaceae). Penstemon attenuatus is a native, perennial forb that grows from a Penstemon attenuatus. Pamela Pavek dense crown to a height of 10 to 90 cm (4 to 35 in). Leaves are dark green, opposite and entire, however the Alternate Names margins of P. attenuatus var. attenuatus leaves are often, Common Alternate Names: taper-leaf penstemon, sulphur at least in part, finely toothed (Strickler 1997). Basal penstemon, sulphur beardtongue (P. attenuatus var. leaves are petiolate, up to 4 cm (1.5 in) wide and 17 cm (7 palustris), south Idaho penstemon (P. attenuatus var. -

Pollination by Deceit in Paphiopedilum Barbigerum (Orchidaceae): a Staminode Exploits the Innate Colour Preferences of Hoverflies (Syrphidae) J

Plant Biology ISSN 1435-8603 RESEARCH PAPER Pollination by deceit in Paphiopedilum barbigerum (Orchidaceae): a staminode exploits the innate colour preferences of hoverflies (Syrphidae) J. Shi1,2, Y.-B. Luo1, P. Bernhardt3, J.-C. Ran4, Z.-J. Liu5 & Q. Zhou6 1 State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 2 Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3 Department of Biology, St Louis University, St Louis, MO, USA 4 Management Bureau of Maolan National Nature Reserve, Libo, Guizhou, China 5 The National Orchid Conservation Center, Shenzhen, China 6 Guizhou Forestry Department, Guiyang, China Keywords ABSTRACT Brood site mimic; food deception; fruit set; olfactory cue; visual cue. Paphiopedilum barbigerum T. Tang et F. T. Wang, a slipper orchid native to southwest China and northern Vietnam, produces deceptive flowers that are Correspondence self-compatible but incapable of mechanical self-pollination (autogamy). The Y.-B. Luo, State Key Laboratory of Systematic flowers are visited by females of Allograpta javana and Episyrphus balteatus and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, (Syrphidae) that disperse the orchid’s massulate pollen onto the receptive Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20 Nanxincun, stigmas. Measurements of insect bodies and floral architecture show that the Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China. physical dimensions of these two fly species correlate with the relative posi- E-mail: [email protected] tions of the receptive stigma and dehiscent anthers of P. barbigerum. These hoverflies land on the slippery centralised wart located on the shiny yellow Editor staminode and then fall backwards through the labellum entrance. -

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017

Harvard Papers in Botany Volume 22, Number 1 June 2017 A Publication of the Harvard University Herbaria Including The Journal of the Arnold Arboretum Arnold Arboretum Botanical Museum Farlow Herbarium Gray Herbarium Oakes Ames Orchid Herbarium ISSN: 1938-2944 Harvard Papers in Botany Initiated in 1989 Harvard Papers in Botany is a refereed journal that welcomes longer monographic and floristic accounts of plants and fungi, as well as papers concerning economic botany, systematic botany, molecular phylogenetics, the history of botany, and relevant and significant bibliographies, as well as book reviews. Harvard Papers in Botany is open to all who wish to contribute. Instructions for Authors http://huh.harvard.edu/pages/manuscript-preparation Manuscript Submission Manuscripts, including tables and figures, should be submitted via email to [email protected]. The text should be in a major word-processing program in either Microsoft Windows, Apple Macintosh, or a compatible format. Authors should include a submission checklist available at http://huh.harvard.edu/files/herbaria/files/submission-checklist.pdf Availability of Current and Back Issues Harvard Papers in Botany publishes two numbers per year, in June and December. The two numbers of volume 18, 2013 comprised the last issue distributed in printed form. Starting with volume 19, 2014, Harvard Papers in Botany became an electronic serial. It is available by subscription from volume 10, 2005 to the present via BioOne (http://www.bioone. org/). The content of the current issue is freely available at the Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries website (http://huh. harvard.edu/pdf-downloads). The content of back issues is also available from JSTOR (http://www.jstor.org/) volume 1, 1989 through volume 12, 2007 with a five-year moving wall. -

Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This Is a Consolidated List Of

RWKiger 26 Jul 18 Literature Cited Robert W. Kiger, Editor This is a consolidated list of all works cited in volumes 24 and 25. In citations of articles, the titles of serials are rendered in the forms recommended in G. D. R. Bridson and E. R. Smith (1991). When those forms are abbreviated, as most are, cross references to the corresponding full serial titles are interpolated here alphabetically by abbreviated form. Two or more works published in the same year by the same author or group of coauthors will be distinguished uniquely and consistently throughout all volumes of Flora of North America by lower-case letters (b, c, d, ...) suffixed to the date for the second and subsequent works in the set. The suffixes are assigned in order of editorial encounter and do not reflect chronological sequence of publication. The first work by any particular author or group from any given year carries the implicit date suffix "a"; thus, the sequence of explicit suffixes begins with "b". Works missing from any suffixed sequence here are ones cited elsewhere in the Flora that are not pertinent in these volumes. Aares, E., M. Nurminiemi, and C. Brochmann. 2000. Incongruent phylogeographies in spite of similar morphology, ecology, and distribution: Phippsia algida and P. concinna (Poaceae) in the North Atlantic region. Pl. Syst. Evol. 220: 241–261. Abh. Senckenberg. Naturf. Ges. = Abhandlungen herausgegeben von der Senckenbergischen naturforschenden Gesellschaft. Acta Biol. Cracov., Ser. Bot. = Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Series Botanica. Acta Horti Bot. Prag. = Acta Horti Botanici Pragensis. Acta Phytotax. Geobot. = Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica. [Shokubutsu Bunrui Chiri.] Acta Phytotax. -

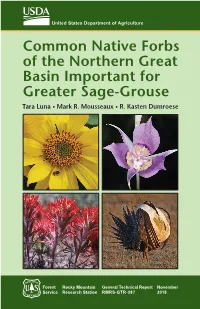

Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R

United States Department of Agriculture Common Native Forbs of the Northern Great Basin Important for Greater Sage-Grouse Tara Luna • Mark R. Mousseaux • R. Kasten Dumroese Forest Rocky Mountain General Technical Report November Service Research Station RMRS-GTR-387 2018 Luna, T.; Mousseaux, M.R.; Dumroese, R.K. 2018. Common native forbs of the northern Great Basin important for Greater Sage-grouse. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-387. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station; Portland, OR: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Oregon–Washington Region. 76p. Abstract: is eld guide is a tool for the identication of 119 common forbs found in the sagebrush rangelands and grasslands of the northern Great Basin. ese forbs are important because they are either browsed directly by Greater Sage-grouse or support invertebrates that are also consumed by the birds. Species are arranged alphabetically by genus and species within families. Each species has a botanical description and one or more color photographs to assist the user. Most descriptions mention the importance of the plant and how it is used by Greater Sage-grouse. A glossary and indices with common and scientic names are provided to facilitate use of the guide. is guide is not intended to be either an inclusive list of species found in the northern Great Basin or a list of species used by Greater Sage-grouse; some other important genera are presented in an appendix. Keywords: diet, forbs, Great Basin, Greater Sage-grouse, identication guide Cover photos: Upper le: Balsamorhiza sagittata, R. -

The Inflorescence and Flowers of Dichrostachys Cinerea, W & A

THE INFLORESCENCE AND FLOWERS OF DICHROSTACHYS CINEREA, W & A BY C. S. VENKATESH (Department of Botany, University of Delhi, Delhi) Received April 14, 1951 (Communicated by Prof. P. Maheshwari, r.A.SC.) THE inflorescences of certain members of the sub-family Mimosoide~e bear polygamous flowers. Geitler (1927) has described this phenomenon in Neptunia oleracea. The results of a similar study of Dichrostachys cinerea, another member of the sub-family, are embodied in the present paper. This plant is of frequent occurrence in the dry forests of India and material collected on the Delhi Ridge last September by Prof. P. Maheshwari was very kindly passed on to me for study. Besides dissections of numerous flowers from several inflorescences, microtome sections of complete young spikes as well as of individual flowers were cut following the customary methods of infiltration and imbedding in paraffin. Some sections were stained with safranin and fast green and others with Heidenhain's iron-alum h~ematoxylin. OBSERVATIONS A portion of a flowering and fruiting twig of the plant is shown in Fig. 1. Exclusive of the stalk, approximately the upper half of the spicate inflorescence bears normal, perfect, bisexual flowers with the floral formula K (5), C (5), A 5, and G 1. The petals are subconnate towards their bases and are bright yellow in colour. The stamens have slender filiform fila- ments. The five stamens opposite the sepals are longer than those oppo- site the petals (Fig. 11). The dorsifixed anthers are four-celled, with the connective prolonged into a conspicuous, stipitate gland (Figs. 17, 18, 29). -

Bee-Mediated Pollen Transfer in Two Populations of Cypripedium Montanum Douglas Ex Lindley

Journal of Pollination Ecology, 13(20), 2014, pp 188-202 BEE-MEDIATED POLLEN TRANSFER IN TWO POPULATIONS OF CYPRIPEDIUM MONTANUM DOUGLAS EX LINDLEY Peter Bernhardt*1, Retha Edens-Meier2, Eric Westhus3, Nan Vance4 1Department of Biology, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 2Department of Educational Studies, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 3Center for Outcomes Research, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103, USA 4P.O. Box 282, Kooskia, ID 83539, USA Abstract—The conversion rate of flowers into fruit in C. montanum at two sites over four seasons was 52-85%, unusually high for a food mimic orchid. Comparative measurements of the trap-like labellum of C. montanum showed it was intermediate in size compared to measurements of six other Cypripedium spp. found in North America and China. While visitors to flowers of C. montanum represented three insect orders, at two sites, over four seasons only small- to medium-sized, solitary bees (5-10 mm in length) carried the pollen massulae. Bee-visitation occurred at both sites and began within 24-48 hours following labellum expansion. Female bees in the genus Lasioglossum (Halictidae) were the most common carriers of massulae. However, species of visiting bees differed between sites and years. At both sites the majority of bees entered and escaped from the labellum in less than 180 seconds and there was no significant difference between the times bees spent in the flowers at both sites. At the site on the Eastside Cascades of Central Oregon, there was no correlation between the length and width of a bee and the time it spent escaping from the basal openings. -

REDUCIDA Fissa.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE BIOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENTO DE BOTÁNICA Y FISIOLOGÍA VEGETAL ÁREA DE BOTÁNICA TESIS DOCTORAL TESIS DOCTORAL Estudio multidisciplinar sobre las especies del complejo de la serie Fissa del género Delphinium en la Península Ibérica, con especial atención a Delphinium fissum subsp. sordidum: implicaciones para la conservación Tesis Doctoral presentada por el Licenciado D. Rubén Ramírez Rodríguez para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universidad de Salamanca Salamanca, 2018 DEPARTAMENTO DE BOTÁNICA Y FISIOLOGÍA VEGETAL ÁREA DE BOTÁNICA La presente Tesis Doctoral está elaborada en el formato de compendio de artículos/publicaciones según la normativa aprobada por la Comisión de Doctorado y Postgrado de la Universidad de Salamanca el 15 de Febrero de 2013 y consta de las siguientes publicaciones: 1. Delphinium fissum subsp. sordidum (Ranunculaceae) in Portugal: distribution and conservation status Rubén Ramírez-Rodríguez1, Leopoldo Medina2, Miguel Menezes de Sequeira3, Carlos Aguiar4 & Francisco Amich1 1Evolution, Taxonomy, and Conservation Group (ECOMED), Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, University of Salamanca, E-37008 Salamanca, Spain; 2Real Jardín Botánico CSIC, Plaza de Murillo 2, ES-28014 Madrid, Spain; 3GBM, Universidade da Madeira, Centro de Ciências da vida, Grupo de Botânica da Madeira, Campus da Penteada, 9000-390 Funchal, Portugal; 4Centro de Investigação de Montanha, Instituto Politécnico de Bragança, Apartado 1172, Bragança 5301-855, Portugal. Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid (2017) 74 -

Phylogeny, Morphology and the Role of Hybridization As Driving Force Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/707588; this version posted July 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Phylogeny, morphology and the role of hybridization as driving force of evolution in 2 grass tribes Aveneae and Poeae (Poaceae) 3 4 Natalia Tkach,1 Julia Schneider,1 Elke Döring,1 Alexandra Wölk,1 Anne Hochbach,1 Jana 5 Nissen,1 Grit Winterfeld,1 Solveig Meyer,1 Jennifer Gabriel,1,2 Matthias H. Hoffmann3 & 6 Martin Röser1 7 8 1 Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Institute of Biology, Geobotany and Botanical 9 Garden, Dept. of Systematic Botany, Neuwerk 21, 06108 Halle, Germany 10 2 Present address: German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), Deutscher 11 Platz 5e, 04103 Leipzig, Germany 12 3 Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, Institute of Biology, Geobotany and Botanical 13 Garden, Am Kirchtor 3, 06108 Halle, Germany 14 15 Addresses for correspondence: Martin Röser, [email protected]; Natalia 16 Tkach, [email protected] 17 18 ABSTRACT 19 To investigate the evolutionary diversification and morphological evolution of grass 20 supertribe Poodae (subfam. Pooideae, Poaceae) we conducted a comprehensive molecular 21 phylogenetic analysis including representatives from most of their accepted genera. We 22 focused on generating a DNA sequence dataset of plastid matK gene–3'trnK exon and trnL– 23 trnF regions and nuclear ribosomal ITS1–5.8S gene–ITS2 and ETS that was taxonomically 24 overlapping as completely as possible (altogether 257 species). -

What Good Is a Sterile Stamen? by Peter Lesica from Kelseya, Summer 2002

What Good Is A Sterile Stamen? By Peter Lesica from Kelseya, Summer 2002 Penstemons are one of our favorite and most familiar groups of native plants. That’s understandable because there are lots of them and most have colorful, showy flowers. In fact, Penstemon is the largest genus of plants among those found only in North America. Of the 250 species, the majority occur in the western U.S. The great diversity of penstemons makes them a great group for gardening, but it also allows us to study how flowers evolve without having to go too far from home. Beardtongue is the common name applied to many members of the genus Penstemon. It refers to the fact that all penstemons have a sterile stamen called a "staminode" that is hairy to some extent in the majority of species. Penstemon flowers are pretty simple, so the staminode is easy to see. Just peel open the corolla. There are six slender, whitish stalks inside. Four have elongate sacs at their tips; these are the fertile stamens, and the sacs contain pollen. One of the two remaining stalks comes from the top of the ovary; this is the style that carries pollen tubes to the young seeds. The other sacless stalk is the staminode. Evolutionary biologists believe that the pollen-bearing function of the staminode was lost during the evolution of penstemon’s two-sided, two-lipped flower from more primitive, radially symmetrical tube flowers. Flowers of these less advanced groups have five functional stamens. But five doesn’t divide evenly into the two halves of the bilaterally symmetrical penstemon flower, so apparently the function of one of the five stamens was lost as flowers evolved toward being two-lipped.