The Qianlong Emperor's Letter to George III and the Early-Twentieth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: the Great Qing and the Maritime World

Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultüt der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Chung-yam PO Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Kurtz Datum: 28 June 2013 Table of Contents Abstract 2 Acknowledgments 3 Emperors of the Qing Dynasty 5 Map of China Coast 6 Introduction 7 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 43 Chapter 2 Modeling the Sea Space 62 Chapter 3 The Dragon Navy 109 Chapter 4 Maritime Customs Office 160 Chapter 5 Writing the Waves 210 Conclusion 247 Glossary 255 Bibliography 257 1 Abstract Most previous scholarship has asserted that the Qing Empire neglected the sea and underestimated the worldwide rise of Western powers in the long eighteenth century. By the time the British crushed the Chinese navy in the so-called Opium Wars, the country and its government were in a state of shock and incapable of quickly catching-up with Western Europe. In contrast with such a narrative, this dissertation shows that the Great Qing was in fact far more aware of global trends than has been commonly assumed. Against the backdrop of the long eighteenth century, the author explores the fundamental historical notions of the Chinese maritime world as a conceptual divide between an inner and an outer sea, whereby administrators, merchants, and intellectuals paid close and intense attention to coastal seawaters. Drawing on archival sources from China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and the West, the author argues that the connection between the Great Qing and the maritime world was complex and sophisticated. -

Russo-Chinese Myths and Their Impact on Japanese Foreign Policy in the 1930S

Title Russo-Chinese Myths and Their Impact on Japanese Foreign Policy in the 1930s Author(s) Paine, S.C.M. Citation Acta Slavica Iaponica, 21, 1-22 Issue Date 2004 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/39429 Type bulletin (article) File Information ASI21_001.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP ACTA SLAVICA IAPONICA TOMUS 21, PP. 1-22 Articles RUSSO-CHINESE MYTHS AND THEIR IMPACT ON JAPANESE FOREIGN POLICY IN THE 1930S S.C.M. PAINE The Far Eastern geopolitical environment of the 1930s was characterized by systemic Chinese instability from an interminable civil war, growing Soviet missionary activities to promote communism, and a collapse of Asian trade brought on by the Great Depression. While Western attention remained rivet- ed on the more local problems of German compliance with the settlement terms of World War I and a depression that seemed to defy all conventional reme- dies, Japan focused with increasing horror on events in China. Japanese poli- cymakers had great difficulty communicating to their Western counterparts their sense of urgency concerning the dangers presented by the unfolding events in Asia. Their task was greatly complicated by the many myths obscuring the true nature of Russo-Chinese relations. These myths then distorted foreign understanding of Sino-Japanese relations. Russia is not usually considered in the context of the Far East. Both of its modern capitals – St. Petersburg and Moscow – are in Europe, its primary cul- tural ties are also with Europe, and yet much of its territory lies beyond the Ural Mountains in the Far East. -

The Interaction Between Ethnic Relations and State Power: a Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Georgia State University Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Sociology Dissertations Department of Sociology 5-27-2008 The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911 Wei Li Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Wei, "The nI teraction between Ethnic Relations and State Power: A Structural Impediment to the Industrialization of China, 1850-1911." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/sociology_diss/33 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Sociology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE INTERACTION BETWEEN ETHNIC RELATIONS AND STATE POWER: A STRUCTURAL IMPEDIMENT TO THE INDUSTRIALIZATION OF CHINA, 1850-1911 by WEI LI Under the Direction of Toshi Kii ABSTRACT The case of late Qing China is of great importance to theories of economic development. This study examines the question of why China’s industrialization was slow between 1865 and 1895 as compared to contemporary Japan’s. Industrialization is measured on four dimensions: sea transport, railway, communications, and the cotton textile industry. I trace the difference between China’s and Japan’s industrialization to government leadership, which includes three aspects: direct governmental investment, government policies at the macro-level, and specific measures and actions to assist selected companies and industries. -

Download File

On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2021 © 2021 Xiaohan Du All Rights Reserved Abstract On A Snowy Night: Yishan Yining (1247-1317) and the Development of Zen Calligraphy in Medieval Japan Xiaohan Du This dissertation is the first monographic study of the monk-calligrapher Yishan Yining (1247- 1317), who was sent to Japan in 1299 as an imperial envoy by Emperor Chengzong (Temur, 1265-1307. r. 1294-1307), and achieved unprecedented success there. Through careful visual analysis of his extant oeuvre, this study situates Yishan’s calligraphy synchronically in the context of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy at the turn of the 14th century and diachronically in the history of the relationship between calligraphy and Buddhism. This study also examines Yishan’s prolific inscriptional practice, in particular the relationship between text and image, and its connection to the rise of ink monochrome landscape painting genre in 14th century Japan. This study fills a gap in the history of Chinese calligraphy, from which monk- calligraphers and their practices have received little attention. It also contributes to existing Japanese scholarship on bokuseki by relating Zen calligraphy to religious and political currents in Kamakura Japan. Furthermore, this study questions the validity of the “China influences Japan” model in the history of calligraphy and proposes a more fluid and nuanced model of synthesis between the wa and the kan (Japanese and Chinese) in examining cultural practices in East Asian culture. -

History, Background, Context

42 History, Background, Context The history of the Qing dynasty is of course the history of hundreds upon hundreds of millions of people. The volume, density, and complexity of the information contained in this history--"history" in the sense of the totality of what really happened and why--even if it were available would be beyond the capacity of any single individual to comprehend. Thus what follows is "history" in another sense--a selective recreation of the past in written form--in this case a sketch of basic facts about major episodes and events drawn from secondary sources which hopefully will provide a little historical background and allow the reader to place Pi Xirui and Jingxue lishi within a historical context. While the history of the Qing dynasty proper begins in 1644, history is continuous. The Jurchen (who would later call themselves Manchus), a northeastern tribal people, had fought together with the Chinese against the Japanese in the 1590s when the Japanese invaded Korea. However in 1609, after a decade of increasing military strength, their position towards the Chinese changed, becoming one of antagonism. Nurhaci1 努爾哈赤 (1559-1626), a leader who had united the Jurchen tribes, proclaimed himself to be their chieftain or Khan in 1616 and also proclaimed the 1See: ECCP, p.594-9, for his biography. 43 founding of a new dynasty, the Jin 金 (also Hou Jin 後金 or Later Jin), signifying that it was a continuation of the earlier Jurchen dynasty which ruled from 1115-1234. In 1618, Nurhaci led an army of 10,000 with the intent of invading China. -

Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China Gregory Adam Scott Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Gregory Adam Scott All Rights Reserved This work may be used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. For more information about that license, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. For other uses, please contact the author. ABSTRACT Conversion by the Book: Buddhist Print Culture in Early Republican China 經典佛化: 民國初期佛教出版文化 Gregory Adam Scott 史瑞戈 In this dissertation I argue that print culture acted as a catalyst for change among Buddhists in modern China. Through examining major publication institutions, publishing projects, and their managers and contributors from the late nineteenth century to the 1920s, I show that the expansion of the scope and variety of printed works, as well as new the social structures surrounding publishing, substantially impacted the activity of Chinese Buddhists. In doing so I hope to contribute to ongoing discussions of the ‘revival’ of Chinese Buddhism in the modern period, and demonstrate that publishing, propelled by new print technologies and new forms of social organization, was a key field of interaction and communication for religious actors during this era, one that helped make possible the introduction and adoption of new forms of religious thought and practice. 本論文的論點是出版文化在近代中國佛教人物之中,扮演了變化觸媒的角色. 通過研究從十 九世紀末到二十世紀二十年代的主要的出版機構, 種類, 及其主辦人物與提供貢獻者, 論文 說明佛教印刷的多元化 以及範圍的大量擴展, 再加上跟出版有關的社會結構, 對中國佛教 人物的活動都發生了顯著的影響. 此研究顯示在被新印刷技術與新形式的社會結構的推進 下的出版事業, 為該時代的宗教人物展開一種新的相互連結與構通的場域, 因而使新的宗教 思想與實踐的引入成為可能. 此論文試圖對現行關於近代中國佛教的所謂'復興'的討論提出 貢獻. Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables iii Acknowledgements v Abbreviations and Conventions ix Works Cited by Abbreviation x Maps of Principle Locations xi Introduction Print Culture and Religion in Modern China 1. -

New Qing History: Dispute, Dialog, and Influence

Faculty Scholarship Collection The faculty at Allegheny College has made this scholarly article openly available through the Faculty Scholarship Collection (FSC). Article Title The Social Construction and Deconstruction of Evil Landlords in Contemporary Chinese Fiction, Art, and Collective Memory Author(s) Guo Wu (Allegheny College) Journal Title Modern Chinese Literature and Culture Citation Wu, Guo. 2013. "The Social Construction and Deconstruction of Evil Landlords in Contemporary Chinese Fiction, Art, and Collective Memory." Modern Chinese Literature and Culture 25, no. 1: 131-164. Link to additional information on http://u.osu.edu/mclc/journal/abstracts/wu-guo/ publisher’s website Version of article in FSC Published version Link to this article through FSC https://dspace.allegheny.edu/handle/10456/37714 Date article added to FSC March 18, 2015 Information about Allegheny’s Open Access Policy is available at http://sites.allegheny.edu/scholarlycommunication/ For additional articles from this collection, visit https://dspace.allegheny.edu/handle/10456/34250 The Chinese Historical Review ISSN: 1547-402X (Print) 2048-7827 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ytcr20 New Qing History: Dispute, Dialog, and Influence Guo Wu To cite this article: Guo Wu (2016) New Qing History: Dispute, Dialog, and Influence, The Chinese Historical Review, 23:1, 47-69, DOI: 10.1080/1547402X.2016.1168180 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1547402X.2016.1168180 Published online: 09 Jun 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 325 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ytcr20 Download by: [Allegheny College] Date: 19 December 2016, At: 07:28 The Chinese Historical Review, 23. -

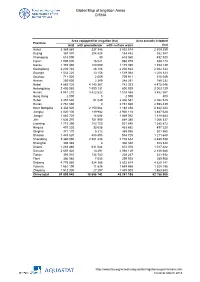

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA

Global Map of Irrigation Areas CHINA Area equipped for irrigation (ha) Area actually irrigated Province total with groundwater with surface water (ha) Anhui 3 369 860 337 346 3 032 514 2 309 259 Beijing 367 870 204 428 163 442 352 387 Chongqing 618 090 30 618 060 432 520 Fujian 1 005 000 16 021 988 979 938 174 Gansu 1 355 480 180 090 1 175 390 1 153 139 Guangdong 2 230 740 28 106 2 202 634 2 042 344 Guangxi 1 532 220 13 156 1 519 064 1 208 323 Guizhou 711 920 2 009 709 911 515 049 Hainan 250 600 2 349 248 251 189 232 Hebei 4 885 720 4 143 367 742 353 4 475 046 Heilongjiang 2 400 060 1 599 131 800 929 2 003 129 Henan 4 941 210 3 422 622 1 518 588 3 862 567 Hong Kong 2 000 0 2 000 800 Hubei 2 457 630 51 049 2 406 581 2 082 525 Hunan 2 761 660 0 2 761 660 2 598 439 Inner Mongolia 3 332 520 2 150 064 1 182 456 2 842 223 Jiangsu 4 020 100 119 982 3 900 118 3 487 628 Jiangxi 1 883 720 14 688 1 869 032 1 818 684 Jilin 1 636 370 751 990 884 380 1 066 337 Liaoning 1 715 390 783 750 931 640 1 385 872 Ningxia 497 220 33 538 463 682 497 220 Qinghai 371 170 5 212 365 958 301 560 Shaanxi 1 443 620 488 895 954 725 1 211 648 Shandong 5 360 090 2 581 448 2 778 642 4 485 538 Shanghai 308 340 0 308 340 308 340 Shanxi 1 283 460 611 084 672 376 1 017 422 Sichuan 2 607 420 13 291 2 594 129 2 140 680 Tianjin 393 010 134 743 258 267 321 932 Tibet 306 980 7 055 299 925 289 908 Xinjiang 4 776 980 924 366 3 852 614 4 629 141 Yunnan 1 561 190 11 635 1 549 555 1 328 186 Zhejiang 1 512 300 27 297 1 485 003 1 463 653 China total 61 899 940 18 658 742 43 241 198 52 -

Memorandum of Understanding Between

Memorandum of Understanding between Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services of the United States of America and Certification and Accreditation Administration of the People's Republic of China Regarding Registration of U.S. Food Manufacturers Exporting to China PREAMBLE The Participants in this Memorandum ofUnderstanding (MOU), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) ofthe United States of America, and the Certification and Accreditation Administration of the People' s Republic of China (CNCA), hereinafter referred to as the "Participants," Recognizing that the Food Safety Law ofthe People's Republic of China and Decree 145 of the General Administration ofQuality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine ofthe People's Republic ofChina (AQSIQ) require overseas manufacturers ofcertain food products offered for entry into China to be under the effective control and supervision offoreign competent authorities; Recognizing that under Decree 145 overseas manufacturers of certain food products offered for entry into China are to be certified by the foreign competent authority exercising control and supervision over such manufacturers to be in compliance with the relevant laws and regulations of China, with respect to the food product categories identified in AQSIQ-related notices; Recognizing that FDA is charged with the enforcement ofthe Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) and, pursuant to the FD&C Act, is charged with protecting public health by ensuring that foods are safe, wholesome, sanitary, and properly labeled, Recognizing that U.S. based food manufacturers ofcertain food products offered for entry into China must be certified to be in compliance with the laws and regulations of China for food product categories identified in AQSIQ-related notices, and such certification is available only from third parties; and Recognizing that the differences between the U.S. -

China, Das Chinesische Meer Und Nordostasien China, the East Asian Seas, and Northeast Asia

China, das Chinesische Meer und Nordostasien China, the East Asian Seas, and Northeast Asia Horses of the Xianbei, 300–600 AD: A Brief Survey Shing MÜLLER1 iNTRODUCTION The Chinese cavalry, though gaining great weight in warfare since Qin and Han times, remained lightly armed until the fourth century. The deployment of heavy armours of iron or leather for mounted warriors, especially for horses, seems to have been an innovation of the steppe peoples on the northern Chinese border since the third century, as indicated in literary sources and by archaeological excavations. Cavalry had become a major striking force of the steppe nomads since the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 AD, thus leading to the warfare being speedy and fierce. Ever since then, horses occupied a crucial role in war and in peace for all steppe riders on the northern borders of China. The horses were selectively bred, well fed, and drilled for war; horses of good breed symbolized high social status and prestige of their owners. Besides, horses had already been the most desired commodities of the Chinese. With superior cavalries, the steppe people intruded into North China from 300 AD onwards,2 and built one after another ephemeral non-Chinese kingdoms in this vast territory. In this age of disunity, known pain- fully by the Chinese as the age of Sixteen States (316–349 AD) and the age of Southern and Northern Dynas- ties (349–581 AD), many Chinese abandoned their homelands in the CentraL Plain and took flight to south of the Huai River, barricaded behind numerous rivers, lakes and hilly landscapes unfavourable for cavalries, until the North and the South reunited under the flag of the Sui (581–618 AD).3 Although warfare on horseback was practised among all northern steppe tribes, the Xianbei or Särbi, who originated from the southeastern quarters of modern Inner Mongolia and Manchuria, emerged as the major power during this period. -

Augustine Henry and the Exploration of the Chinese Flora

Augustine Henry and the E. Charles Nelson Exploration of the Chinese Flora The plant-collector’s job is to uncover the hidden studies as rapidly as he could, obtained his beauties of the world, so that others may share medical qualifications, passed the Chinese his joy .... Customs Service examinations, for which he - Frank From China to Hkamti Kingdon Ward, had acquired a working knowledge of Long Chinese, and left for China in the autumn of Although he is generally believed to have 1881. been born in Ireland, Augustine Henry was Henry remained in the customs service born in Dundee, Scotland, on July 2, 1857. until the end of 1900, during which time he His father, Bernard, was a native of County made considerable collections of the native Derry in the North of Ireland, and his Chinese flora. Ernest Wilson is reported to - mother was a local girl, Mary MacNamee. have said that "no one in any age has con- She met Bernard Henry while he was visit- tributed more to the knowledge of Chinese ing his married sister, who lived in Dundee. plants than this scholarly Irishman," and in After their marriage, and shortly after Au- Bernard and re- gustine’s birth, Mary Henry The portrait of Augustine Henry in this photo- turned to Ireland with their son and settled graph hangs in the National Botanic Gardens in in Cookstown in County Tyrone. Bernard Dublin, Ireland. It was pamted by Celia Harrison. owned a grocery shop in the town and also bought and sold flax. Austin, as Augustine was called, went to Cookstown Academy. -

Staking Claims to China's Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- Building In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Staking Claims to China’s Borderland: Oil, Ores and State- building in Xinjiang Province, 1893-1964 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Judd Creighton Kinzley Committee in charge: Professor Joseph Esherick, Co-chair Professor Paul Pickowicz, Co-chair Professor Barry Naughton Professor Jeremy Prestholdt Professor Sarah Schneewind 2012 Copyright Judd Creighton Kinzley, 2012 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Judd Creighton Kinzley is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-chair Co- chair University of California, San Diego 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgments.............................................................................................................. vi Vita ..................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ................................................................................................................................x Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1